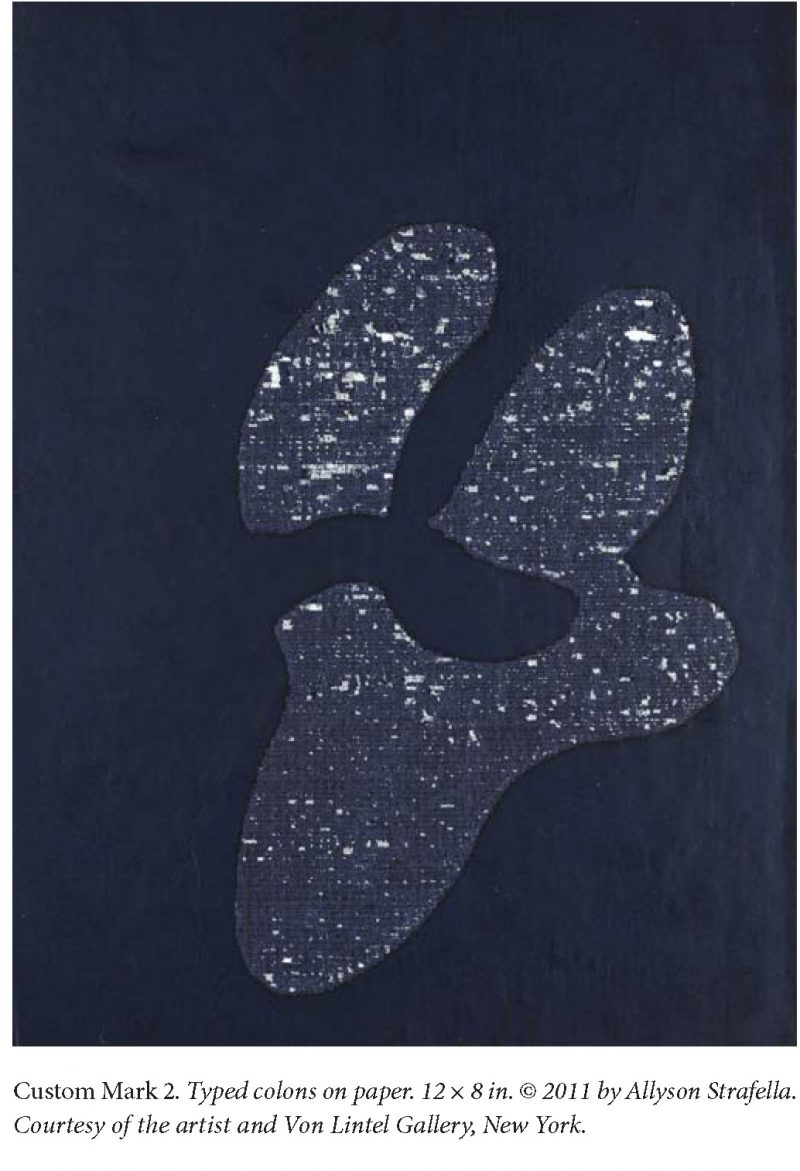

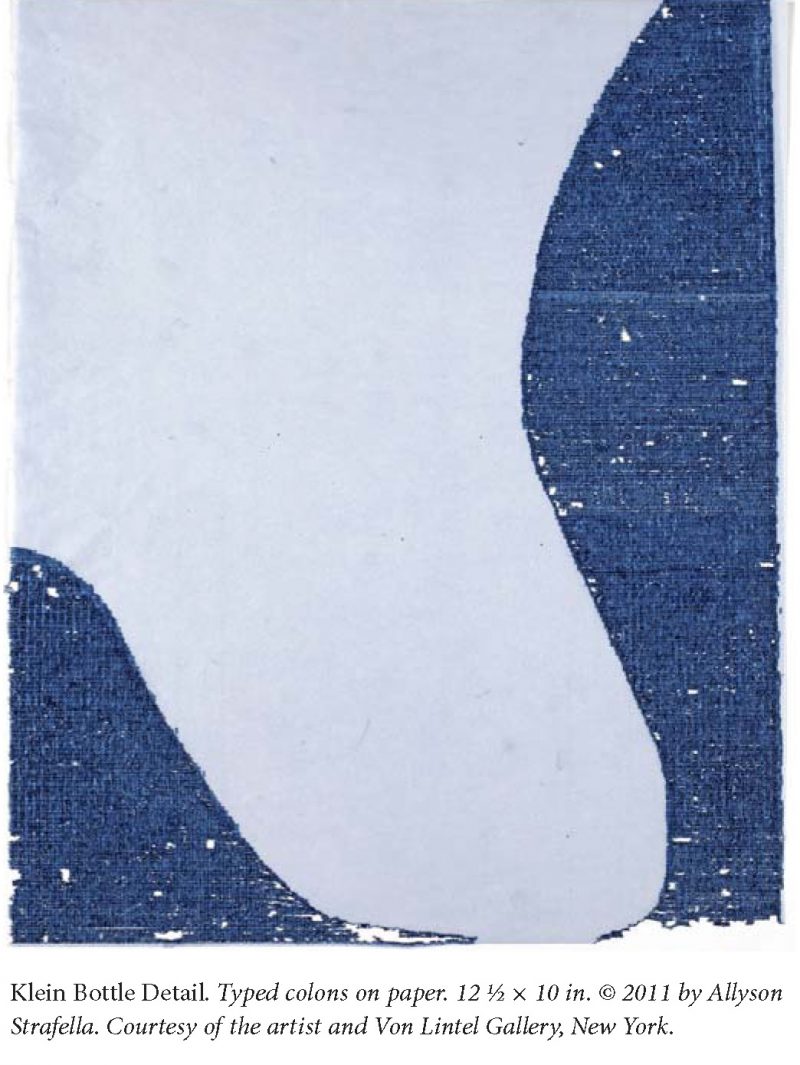

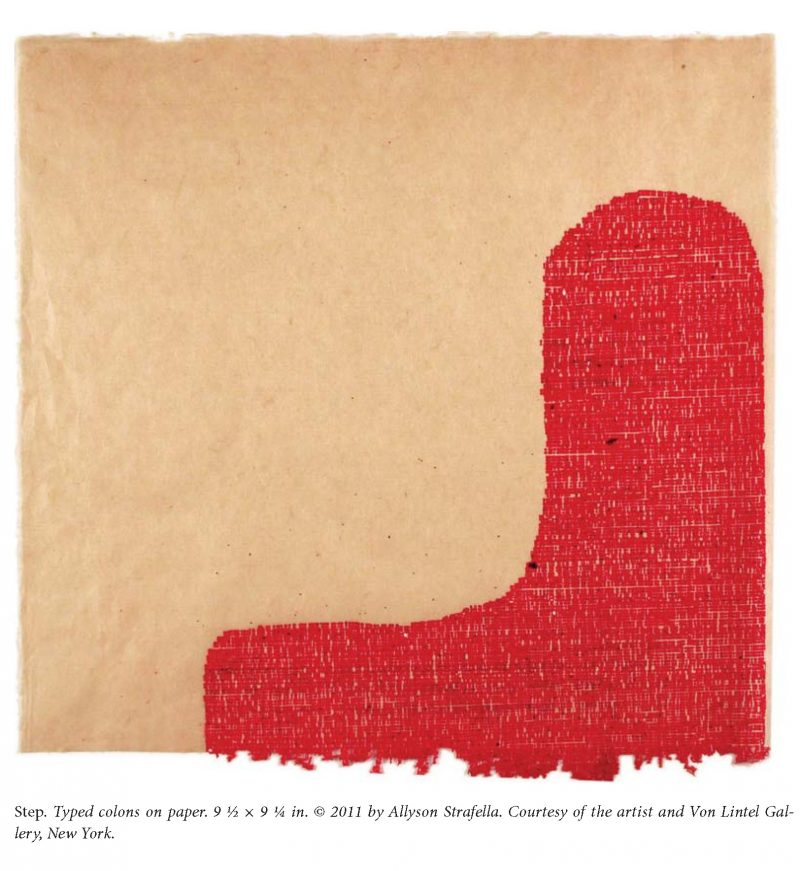

Allyson Strafella can draw with a typewriter, a skill she’s honed over nineteen years of working with a number of Smith Coronas, special transfer papers, and a machinist willing to crack the typewriter open and retool it for her. In some cases, the drawings are made entirely with a colon, a hyphen, or a symbol from Strafella’s own lexicon, punched with extraordinary repetition through colored transfer paper. Some of these gorgeous works have been compared to Ellsworth Kelly’s prints, large geometric blocks of color.

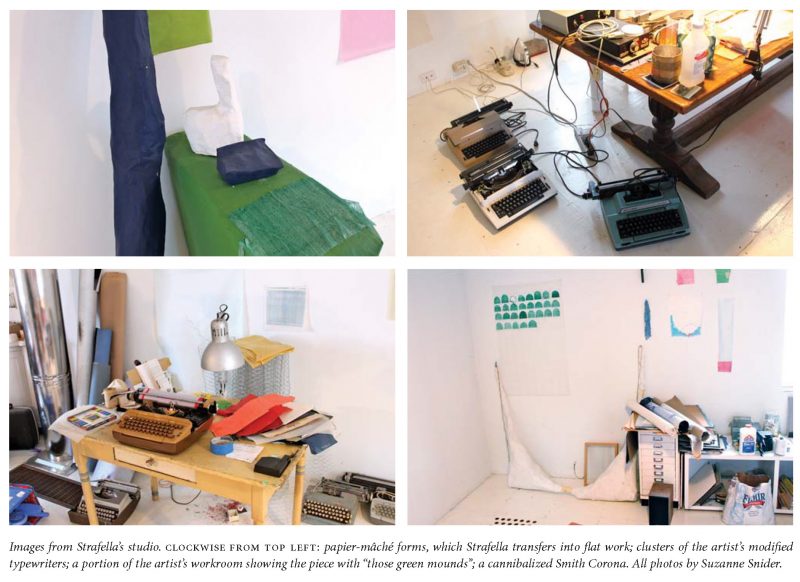

We met one afternoon in her studio, in Hudson, New York, situated on the top level of a two-story barnlike building in the back of the home that she shares with her husband, Max, also an artist (his studio occupies the building’s first floor), and her two children, Miles and Pepper. Between the two buildings are a densely planted garden and a trapezoidal beehive, designed and built by Max.

—Suzanne Snider

I. THE COLON

ALLYSON STRAFELLA: The reason I draw with a typewriter is because of my insecurity about writing. I’d get all tensed up when I had to write papers in school, and I’d run to my sister, who was a journalism major. I just never felt confident about it. So I’d bicycle to school every day, to the library, and I would sit down and just write on the typewriter, stream of consciousness: all lowercase, no punctuation. I would write about what I encountered on the way. I might arrive at something in my work or something I wanted to learn more about. That’s how the typewriter came to me: to relieve myself of all the angst of formal writing and how to use language properly. I sort of broke it down.

One day I sat down and I thought, I’m thinking too long before I write. The first drawing I made was a grid, made of a dotted line: a dash. That was revolutionary for me. It was exactly what I’d been trying to find, because I was in school, in sculpture, and I was always trying to find my center, like, Where do I work from? What is my place that I work out from? So that grid was like, Oh that is my center. That’s the foundation of my work. I was in living in Watertown, in art school at the time, and I remember just sitting there at my desk and it was that “aha” moment. It sounds so corny and silly, but it was like, Oh my god. I have not stopped making drawings since I did that. That was in 1992 or ’93.

THE BELIEVER: Tell me about all these typewriters in your studio.

AS: I draw only with electric typewriters, which people usually find disappointing. I think they like the idea of me sitting and hammering on a manual. Some are here because I love them as objects. Most are Smith Coronas. The first typewriter I used was my father’s—also a Smith Corona. That one on the white bureau-y thing [pointing] has a sweet personality. Some of the others are here because they’ve been used, or I’m trying to figure out if I can use them. The typewriters I choose not to collect are machines that have a language other than the one I speak. I’ve never been comfortable taking on a typewriter that’s Hindi or Braille or Greek or any other language that is one that I don’t know intimately. I think, also, this is a way for me to further define what my language is, by actually building it and making it and owning it in that way

BLVR: That’s interesting, because the colon is a symbol you favor in your drawings, and that certainly would be on some other typewriters, right, in other languages?

AS: Maybe not on Hindi or Hebrew or Chinese or Japanese, but probably on more European-speaking typewriters: Italian, German, French might have it. I hadn’t thought of that.

BLVR: Did your fascination with the colon start aesthetically or was it more in terms of how it functions in a sentence?

AS: Well, it’s both, but I am more conscious of the aesthetic. If you think about a colon, it’s sort of a pause; it punctuates something that you’re going to then follow with something else. But when you just look at it, it’s abstract—just these two dots, two marks, a pair.

II. TYPEWRITERS AND SHOTGUNS

What stands out in Strafella’s studio is one particular typewriter with an oversize carriage that extends well beyond the typewriter’s body. Frankenstein-like, the typewriter has a prime spot on a worktable. If Strafella is interested in engaging with language, she is interested in inventing one, too: each key, as it turns out, hammers onto the paper a set of lines that are part of Strafella’s invented lexicon.

AS: This typewriter is a Smith Corona body, but I worked with this great machinist, Tom Curran, who’s actually now the mayor of Chatham [New York], to build a customized typewriter. He cannibalized this Smith Corona and put a thirty-six-inch carriage on it, so I could draw bigger—and the marks inside are now my marks. What I mean is that they come from drawings. I would take fragments or pieces of a drawing and I would just zoom in as much as I could, and then I would isolate a section. And that would become a new mark.

BLVR: So each key, or “mark,” comes from a previous drawing made with traditional keys?

AS: Right. This was the plan: to work with someone who could rebuild a typewriter for me with my own marks. The other goal was to work on a larger scale. The mark remains the same size, but the page could be up to thirty-six inches wide. There are twenty-nine new marks in the typewriter, new keys, and the rest I left the way they were. I kept the colon as it is because I do love that mark. Typewriters have uppercase and lowercase, so I took advantage of the space: each one of my marks is on a key as an outline and as a solid form. If I shift on the typewriter, I have a solid form, and if I don’t shift it’s just the line, the contour drawing of the form.

BLVR: Once you replaced the letters with symbols on this typewriter, what was your guide when you sat down to work?

AS: I made a visual lexicon of them, so I know which mark the A is, I know which mark the K is…That drawing over there with all those green mounds? Each mound was made with one mark. There are some marks that I do gravitate more toward. I’m still in the very early stages of this machine.

BLVR: What does Tom work on when he isn’t working on your typewriter?

AS: Tom machines parts for anyone who needs that skill, but in his own time he makes really beautiful shotguns, not as weapons but as objects.

BLVR: Donald Judd worked with a lot of fabricators of steel and metal who had never worked with an artist before, and now these fabricators are being interviewed for an oralhistory project, because they’re the only ones who know how to repair the work.

AS: It made me think a lot more about wanting to collaborate with people other than artists. I mean, it’s nice to have peers and people who you can have an exchange with, but it’s way more creative to work with someone else who’s outside of your field, because it does challenge you and it forces you to become clearer about what you’re doing.

BLVR: You can speak in shorthand with another artist, but speaking in shorthand doesn’t always serve us well. I recognize a sculpture here in your studio as a form matching one of your drawings.

AS: There’s a form that I’ve been kind of obsessed with for a number of years: a specific hill in the town of Philmont that I pass by a lot. I thought, I’m going to build that mound. I ended up using papier-mâché, essentially because it’s inexpensive. It’s, like, paper and flour, so even if I don’t have money I can still do that. I made this mound, which is the most two-dimensional three-dimensional object. I find it really very funny. It’s so flat, but I love it. I see a lot of my drawings as sculpture, so periodically I hit a point where I need to make what I call a “three-dimensional drawing.” I need to build the drawing.

BLVR: How do you know when a drawing’s done?

AS: I don’t put a drawing through the typewriter more than once, usually. I won’t take a drawing from four years ago and alter it by putting it through the typewriter again. I won’t. A lot of times it’s because of the physicality of the paper— it wouldn’t survive. Some drawings are clearly done because they’re just solid.

BLVR: I am fascinated to watch you handle the work. Could you talk about the fragility of some of the materials and the way you physically interact with them?

AS: The reason I use a typewriter and not a computer is that the typewriter pounds the paper. It’s a really forceful mechanical gesture and it really embeds the mark in the paper, sometimes to the point where the paper breaks and it splits. That’s what I love about the typewriter—that it transforms the paper into something else. Sometimes pieces of the drawing have fallen off because the paper is so tattered and worn.

When I first started drawing, I’d go into the local office-supply store and buy my carbon and typewriter paper, and I learned quickly that paper—the kind we use for a printer—has a lot of weight. I’m forever trying to find a way to have the thinnest paper possible, so it’s just like a carrier for the mark. I’m always wanting thin paper that’s barely there, which also immediately makes it fragile, and then I’m hammering onto it and breaking it. It can be fragile, but I don’t treat it like it’s fragile. It’s solid, it’s hard, it’s built; it’s organic, mostly, which means that it will fall apart. It’s about breaking down. I’ve been breaking down language. That’s how it all started. BLVR: How did you come to add carbon paper to your work?

AS: I discovered that carbon is so rich and dense. There’s one in particular—it’s almost like velvet and ash when the drawing is done. So that kind of opened up the possibilities of color, too: green, this really beautiful red, and dark blue. Before those carbons, I was into transfer papers that architects use, and then there’s sewing paper, with a chalky surface, for patterns, in blue, yellow, red, orange, white. I have this incredible oily carbon paper, baby blue, that I got from someone whose father had a press out of his basement, like a political press he was running. Someone had her mother send me sewing paper from South Africa, this beautiful green.

BLVR: Do you ever fear that the transfer paper will become obsolete?

AS: Yes, absolutely, just like I thought the typewriter would disappear—but there is eBay. Truth be told, I have enough carbon and transfer paper in this studio to last me for the rest of my life. I think it’s more that fear of the loss of it, so wanting to hoard it and have it preserved. But do I need it? Not really. If I just had black and white for the rest of my life that would be OK, too, because it’s endless, still.

III. GOING INTO THE PAPER

Strafella has lived in upstate New York for ten years. Recently, her son, Miles, has started second grade at a local Waldorf school, where the curriculum is based on Rudolph Steiner’s pedagogy. Just as Steiner had special ideas about when a child should start to read, Waldorf education has specific ideas about art-making, too.

BLVR: This steady expansion from your original grid gives the impression that you’ve had this kind of continual thrust forward, work-wise. Was there a time in all these years that you stopped making art or wanted to stop making art?

AS: I haven’t really stopped. There have been gaps of slowness. I’m just a slow person in the way I think about things and arrive at something and actually do it. I don’t see making art or calling myself an artist meaning that I come into my studio for x amount of hours and make a something: a drawing, an object. That has never really felt comfortable to me, because I think about making art as something that carries through your daily life. I don’t have to be in my studio to be thinking about things or collecting ideas. A lot of what I bring into this studio is from the experience I have outside of it. Like I was saying, nature and the landscape are a big part of what kind of excites me and influences me and gives me a lot to think about. Living in Columbia County, it’s an appealing landscape. If I’m driving around here, I’m looking and accumulating and thinking and imagining.

There are times when I think there’s really no value in making art… I mean, the state of the world is in such a crisis now, and it’s so precarious, that it’s hard to come in and feel like making a drawing. That just seems so self- indulgent and disconnected from the larger world. How do you participate in the larger world if you’re making a drawing? I’ve always had that conflict about the value of art in the world where there’s so much suffering and need for kindness and gestures and helping others. So I have these periods in which I decide I really should do something else, and think, You really can’t make a living as an artist, anyway, so I should do this or I should do that.

The things that I usually want to do are things that come back into my studio, anyway. My husband, Max, and I have bees. I was really interested in honeybees, so that is something that gives to me in my studio. Homeopathy really interests me, and holistic medicine interests me, and those are all things that draw on nature and the body and the true nature of the body in its pure form. I always think maybe I should go back to school. I don’t know that I would really save the world by doing any of those things. Being a social worker was a pull for a long time, or doing something in terms of the body and medicine and healing and nutrition, but it’s always tricky. I’m always trying to think about how to bridge the outside world and the studio. I still don’t know. I’m never going to save the world by making a drawing, or by having a garden or teaching my son about gardening and honeybees. Maybe that’s a small step, like passing something on, or educating someone and therefore educating myself, and having it come back into the work.

As you get older—it’s not that I lost the question of what value art really has in the world, but you just move through it differently as you live life longer and you have other experiences. I’ll always make my work, whatever form it takes. For me, the ideal situation is to have a studio on a plot of land where I’m working outside doing experiments, having the landscape as a piece of paper, as a material to work with, and just the relationship of the outside world and the inside. At this point I often have the pull to help people or take care of someone. I haven’t quite figured out how to satisfy that need or desire. I really don’t think it’s from drawing.

BLVR: To an outsider, two artists living together might seem ideal. Can you say a little bit about being partnered with an artist and raising a family?

AS: Max is a very different artist than I am. He is someone who needs to be in the studio, and he’s always gathering, researching, and working. I think he sees the studio like it’s very established, this place. If he doesn’t get in the studio enough, it can create a lot of angst. I don’t have that so much. But again, it’s because we work differently, the materials, and what we make ends up being very different. When we first moved to Hudson and got this house, we both saw it as material—as this sculpture that we could do anything we wanted to do with it. We could make holes in walls, we could build things, we could remove things. Just over time and with a child, we haven’t done as much in terms of acting on our ideas. But we still get a lot of pleasure out of talking about the what-ifs and the possibilities of how we could use this house, how we could transform it. Being an artist, if you can get through it day by day, surviving and paying your bills, the basic needs, then it’s a pretty expansive life.

BLVR: I know your son is very connected to what you make. How would you describe his relationship to your process and to your art?

AS: I was in here typing away on typewriters when he was in my belly, so that sound has just kind of been with him as long as he could hear it from the inside. He’s probably one of the only kids of his generation who will grow up knowing what a typewriter is and how to use it.

BLVR: He’s going to a Waldorf school during the day. What are some of the ideas you’ve been exposed to, in terms of Steiner and Waldorf ideas of art-making?

AS: Oh, man, Steiner has a lot of wonderful things to offer a small child, and a lot of challenging things. Waldorf has an aesthetic, and art that comes out of Waldorf schools—it’s a certain style. The individual isn’t really there, I think, because they’re all being schooled to use these specific tools: beeswax crayons, which are beautiful objects, they’re the rainbow colors. It’s all very beautiful, but it would be more beautiful if a child was really coming to their own way of using those tools rather than having everything be so fanned and wispy, beautifully contained and all about movement and flow. I feel critical of it because it seems really rigid—like, the color black is not used. I don’t have a big attachment to having a black crayon or a black marker… I should appreciate the limitations, but sometimes I’m critical of it.

A lot of things are wonderful about it for Miles besides the drawing side. He doesn’t so much love to draw yet. Max and I don’t want to instruct him on what to draw or how to draw. I think in Waldorf there is a little bit more instruction.

BLVR: How do the kids end up making wispy drawings? What kinds of prompts encourage that?

AS: I think it’s the nature of the beeswax tool and the kind of paper. They’re probably not using a lot of pressure and it’s very full strokes on the side, like if you think of a crayon, using the side rather than the point. Also the movement of the body. I think Waldorf’s very much into the physical body and how it moves, and so therefore how you’re moving through making a mark as a gesture.

There are no hard edges in Waldorf. The pages all have curved edges. That right there is already stepping outside of the real world by eliminating one thing that’s very much in our world: straight lines. I don’t know why a child can’t draw on a piece of paper that has four corners. I don’t think it’s going to damage their creativity. I think it’s about all this softness and nurturing and loving and wanting to do this to the child to sort of protect them, let them be in a bubble of childhood as long as possible.

The one thing I think is really going to be exciting is learning the alphabet: they’re really into making the gesture in the air, the experience of using your body and making that letter—using your foot to outline that letter in the dirt.

I’ll go all the way back to Vito Acconci, who spoke when I was in school and has influenced me to this day. He’s really amazing, and the most interesting point for me is how he went from being a poet to performance to artmaking: objects. I think for him it was the restriction of the paper; he couldn’t go in this way so he had to come out into the world, the physical world. For me, that idea of a form on the paper and going inside—that’s the direction I’ve gone in. At least conceptually, I think of moving into the paper.

Years ago, I thought a lot about what a letter is. It’s just a line. It’s curved, it’s bent, it’s angular, but if you were to really unravel the letters of the alphabet, you’d have a line. At one point I was a little stuck in my work. I was at Yaddo, and I was thinking a lot about letters and about Vito Acconci moving out of the paper and me moving into the paper. I did a whole bunch of line drawings for a while, and it was that thought of unraveling font and having line. So I did these line drawings where it was just, like, an underline, and then I would put the paper through again and again, and I had this idea of not only the secretary gone mad but more just like this unraveling of text and the building up of lines, of marks, to the point where I’d have a page that was so black. That page could then be turned over and used as carbon, and a drawing could be made with it. That whole thought process was something I carried from Vito Acconci.

BLVR: It’s interesting that you start with this idea of repetition being good and necessary. When I think of sitting at my typewriter and repeating something over and over, it’s a writer’s Kafka nightmare.

AS: When I first started drawing, in the beginning, I was very tuned in to the rhythm and the sound of the keys, and I was counting. I was counting space and building a form. That’s sort of comforting. It’s like meditation. Now a lot of times I’m thinking while I’m typing, thinking about another form, or another drawing, or looking up and seeing what’s on my wall. It doesn’t have my full, focused attention like it used to. The sound is so much a part of the process.

IV. THE RADIO DRAWING SHOW

In September 2010, WGXC, a community radio station for New York’s Columbia and Greene counties, was launched, with its studio based in Hudson, New York. The station airs everything from agricultural news to transmission arts. In town, it’s not uncommon for the station to come up in conversation, and many Hudsonites have directed their daydreams toward the station, dreaming about what kind of radio show they’d host if they had one.

BLVR: You just reminded me of another brilliant idea you had: your drawing show.

AS: Right. I’m always looking at things, so I was wondering: what would a radio show about drawing be like? I have no interest in instructing someone on how to make a drawing. I realized it would be about looking and about seeing, and I think also because we live in the Hudson Valley and there’s this history and this school: the Hudson Valley painters. All these painters were influenced by nature and the landscape. It would be a real challenge. How do you talk about something that is really visual when no one’s seeing it? I could talk through a drawing. I could type the drawing and record it.

BLVR: In a way, it’s a social experiment, too. Being alone and creating, but being guided by a voice. The voice is a prompt, encouragement, and company. I would like to be alone with that voice. [Pause] What are your earliest memories of art-making?

AS: I was always making things as a child. Everyone always thought, artist, because I was always off on my own, wanting to make things. When I think about the work I made to apply to college, it’s so humiliating. It’s like looking at your high-school yearbook. It’s like, Oh my god, that’s so awful.

BLVR: What was it like?

AS: I had an idea that I was supposed to draw so you could identify what it was: it’s supposed to look like a tree or a portrait. I loved straight lines so much because I cannot draw a straight line. I do not make things realistic. I felt that you had to draw things realistically.

When I first started school, going to figure-drawing class—I can’t draw the figure. I hated that class. And now it’s actually really appealing to think about going to a figure class, because I’ve come to really know what my language is and how I see things. It’s like written language: I had to break it down to find my voice in it, and that’s how I am with visual things. It’s always about: how do I break it down to sort of simplify so I can see what I need to see?

BLVR: How do you think you would approach it if you did go to a figure class (which we should do)?

AS: I would just sort of look at it like I look at the rolling hills of Columbia County, and just sort of find what I needed to find in it—find the forms within it and break it down, and not try to put it together as a figure.

BLVR: We haven’t talked about living in a small town yet. Do you think it’s conducive to making the work and life that you want?

AS: I moved from Brooklyn, where I had a studio, and being in the city is so distracting. For me, it was always a battle, because I wanted to shut it out and have quiet so that I could work and know that the work was true, without feeling something was influencing me that really wasn’t genuine or necessary. I’m pretty sensitive to sound and visual space, even though our house here can be really crazy and messy sometimes. So coming to Hudson, I had this day-dreamy kind of idea of living in a small town where you know the person you buy the paper from and know where you get your coffee and know the farmer you buy your vegetables from. I’m also someone who’s not such an extrovert, and I can spend a lot of time alone. If I’m not with my family, I can happily be on my own. I mostly have felt anonymous here in Hudson because what I do is not public. I assume everyone knows nothing about me and that people may only recognize me just because of Max and the radio station, but I really feel like I’m a ghost in this town, and I can watch everyone and observe but no one is watching me and no one knows anything about me.

BLVR: It’s amazing that you’ve maintained that.

AS: I’m just someone who has a closed-door policy, especially in the studio. Not too many people have been in here.