In many ways, I am an unlikely choice of interviewer for a subject like Annie Leibovitz. While I am trained as a photographer and still utilize photography across my work, for the most part I no longer author my own pictures. So I was skeptical when the call came: Were the editors of The Believer sure they wanted me for the job? Wouldn’t the magazine do better with someone more closely aligned with Leibovitz’s work—straddling the art, reportage, and editorial worlds as it does? But deep down I felt this request was tugging on my young self: As a teenager growing up in 1990s Philadelphia, I obsessively collected Leibovitz’s pictures from magazines, taping them up all over my walls, such that the walls, in fact, disappeared under their many layers. Gap ads, Rolling Stone magazine covers, and, most of all, pictures from the “got milk?” campaign filled my little room by the hundreds. I was, it might be noted, unaware that these were her pictures. At that point, I didn’t know anything about who made the images I was obsessed with, images I wanted to live with and inside. I had only my teenage desires to guide me. And they propelled me toward her at full tilt.

Almost three decades later, on this occasion, I miraculously got the chance to speak to Leibovitz, the person who had informed my own burgeoning photographic consciousness, curiosity, and ambition. I once heard someone say that we are all born with Beatles lyrics in our heads, so deep is their creative mark on the world. The same might be said for Leibovitz’s pictures (as evidenced by my own teenage image-collecting pursuits): she has been making this work for so many decades, and with such consistency, innovation, and panache, that it feels hard to imagine the cultural landscape without her impression.

Leibovitz grew up in Connecticut in a large Jewish family; her father was in the air force, and her mother was engaged in art and dance (Leibovitz herself often refers to photographing as a kind of choreography). After graduating from art school at the now-closed San Francisco Art Institute—and living on a kibbutz in Israel for several months—she quickly became the chief photographer for Rolling Stone in 1973. Leibovitz has photographed at a wild pace ever since, making some of the most iconic portraits of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: from John and Yoko in bed; to incarcerated people in Soledad State Prison hugging family members; to a young Whoopi Goldberg in a bathtub full of milk; to Demi Moore, nude and pregnant, on the cover of Vanity Fair. In addition to regularly shooting covers and features for that magazine and Vogue, Leibovitz has had exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and the National Portrait Gallery.

Our conversation unfolded over Zoom on a warm October morning (I was in the Midwest, and she was in New York City), and after a handful of rescheduling emails. It centered on artistic process—sketching, editing, and more—while also delving into her new show at Hauser & Wirth, titled Stream of Consciousness. The show includes seventy images, from throughout her career, and largely centers creative thinkers and makers as subjects. We also discussed my work—a surprise to me!—with regard to my use of archival photography and how we relate to images in relation. We talked about Leibovitz’s decision not to publish pictures of her children, attending synagogue, camera phones, photographing Kamala Harris in the final weeks of the 2024 presidential campaign, and why she feels photojournalism is the most exciting work happening in the field.

—Carmen Winant

I. WEAK IN THE KNEES FOR HOCKNEY

THE BELIEVER: Ready to start?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Let me get some water here. I just drove in at six o’clock this morning from upstate, so I’m a little bit…

BLVR: Tired?

AL: And then I had a call with these publishers; my rabbi, Rabbi [Angela] Buchdahl, needs a photograph, so it was great to have a conversation with her publishers about what they would like to do.

BLVR: What temple do you go to?

AL: Central Synagogue [in New York City]. My three daughters were all bat mitzvahed there.

BLVR: How nice—and that you are photographing your rabbi too.

AL: She is an extraordinary woman. You know, she’s Korean American, actually. Her sermons are quite extraordinary. I mean, the only reason I’m still at this synagogue is because of her. You look forward to her, to what she’s going to say. Where do you live now?

BLVR: I live in Columbus, Ohio.

AL: I read about you, and that was part of the reason I put the interview off. I went, Oh shit. She’s serious. She’s fucking serious.

BLVR: You’re giving me too much credit, I think.

AL: No, no, no. You are a serious artist, and, you know, I crawled into bed the night before and started to do my due diligence, and I called [my studio manager] Karen Mulligan. I said, “I can’t do this tomorrow morning. First of all, she’s too serious.” I mean, I think it’s interesting what you’re doing, the way you’re using photography.

BLVR: I appreciate that. I’ll carry it with me.

AL: Certainly. The older I get, and with the accumulation of the work I have, it is so interesting to see the relationships between the photographs. That’s kind of what I’m interested in in the show I’m having at Hauser & Wirth. The gallery world, it’s such a strange animal, you know?

BLVR: I have questions for you about this, so don’t get too far ahead of me! But first, I want to ask you about photographing such famous subjects. These are people that are used to being photographed; I imagine that makes your job both easier and harder. How does your process differ, if at all, from photographing noncelebrities?

AL: I mean, I’ve been doing this, what, fifty years. It started with journalism. Or what I thought was journalism. I admired the photo story, you know? When I started working for Rolling Stone, I really thought I was doing journalism. And then I quickly realized I wasn’t, because I had a point of view. I found that my work was stronger if I went with that point of view. So the work evolved. It started with these incredible years at Rolling Stone. When I look at that work, I see a young, insane, obsessed photographer. Just, you know, photographing everything in front of me, never going home, really just working all the time. It was a great school for observation and learning and becoming a better photographer. Rolling Stone and I grew up together, and eventually, with the magazine, I began learning how to photograph people. Coming from that place, it was very awkward making portraits at first, because you had an… appointment with someone. It wasn’t as fluid as just being able to be around and watching something evolve or happen.

So what happened? My subjects were sitting for photographs, and I became a little bit more inventive and conceptual. I had a whole slew of very, very conceptual years. Of course, there’s no going back after you start working like that. Now I’m kind of like a dinosaur when it comes to what I do, which is sort of a sitting portrait. I became very aware of what it is I am doing, and feel very responsible to it—to sitting photograph. I’m very interested in it and how to make it work.

As for working with people who are very, very famous and aren’t very famous, I think you’ll see, if you look through all my work, that it’s a mixture. Also, in a lot of the work, I photograph people who aren’t famous yet, and then they’re suddenly famous. When I did Whoopi Goldberg [in 1984], she was unknown. I just went to her apartment in Berkeley and photographed her there. So I’m just saying, these people sometimes become famous after the fact.

BLVR: It’s interesting: The way I set up that initial question was sort of a way to ask, What is it like to photograph famous subjects versus non-famous ones? But what I heard in your answer was a far more interesting distinction: between photojournalism and portraiture.

AL: Yes, yes. The reality is that I love photography—every part of it. There are so many ways to use photography. I mean, it’s so big. I never wanted to be pinned down to one kind of style or work. I have a huge photography book collection. I have a few photographs that I own, Robert Frank and Cartier-Bresson, and people I grew up on whose work I loved.

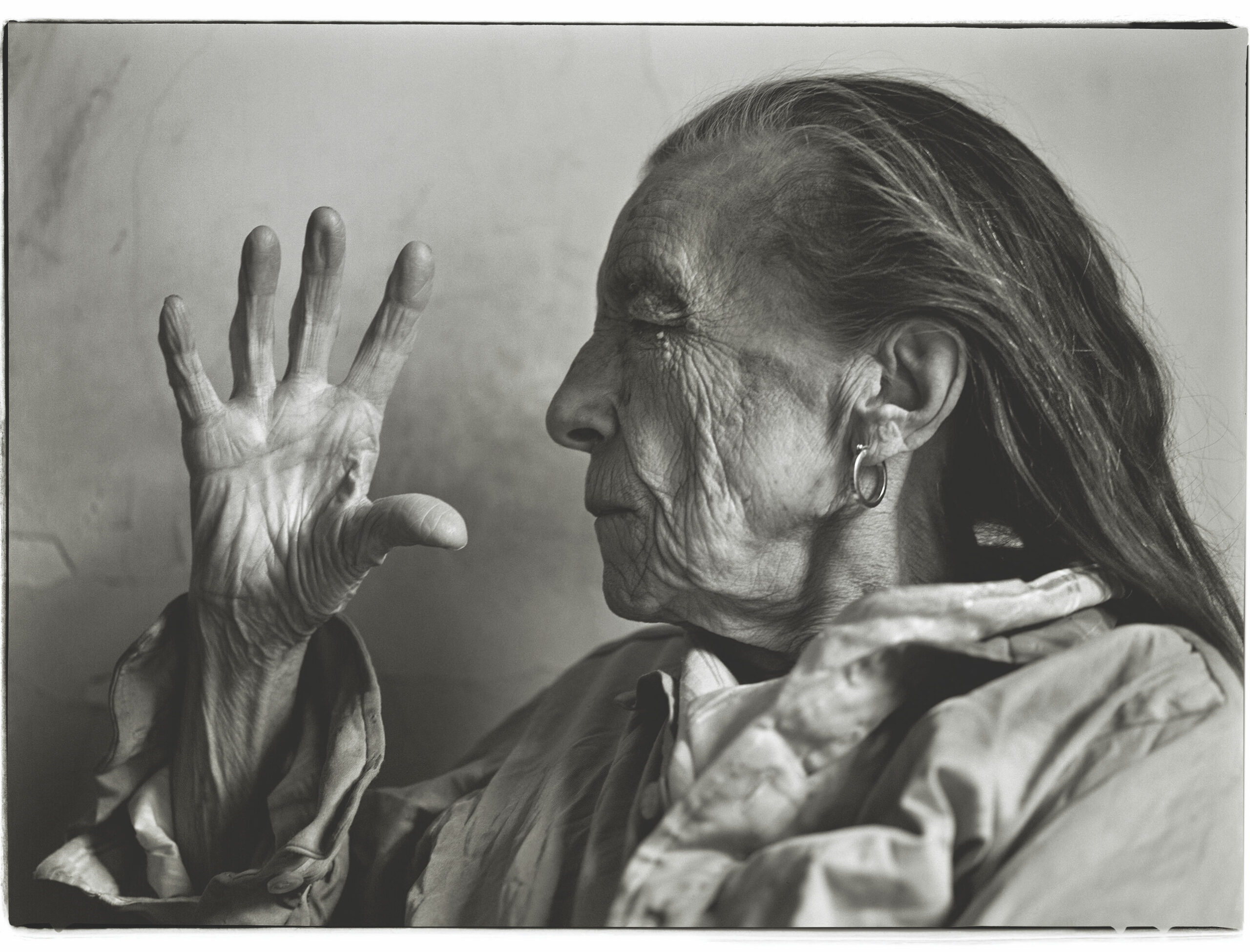

I just went to a Carrie Mae Weems show up at Bard [College], and I couldn’t believe it. To go through every single room and see how she used photography—it was just stunning to me to see the breadth of her ideas. I remember seeing her very early work, with the kitchen photographs [the Kitchen Table Series, 1990], and thinking, Oh my gosh, here goes art photography, whatever it is. But art photography always has been interesting, quite honestly. Hockney was the first person to do it, when he did his study on perspective. I remember being weak in the knees, thinking, That’s how the eye sees—the way he collaged his pictures together. I was so frustrated with the frame of the camera then—that everything had to be in that frame. We learned with Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank to compose in that rectangle, and to use the whole negative. But now it’s so wide open, and it’s so interesting, and it’s such a great medium. It deserves to be, and it is, now, taken seriously. It is art. It’s great to live through all that.

II. SITTING POLITICIANS

BLVR: As for sitting portraits, the most recent photograph of yours that I’ve seen published is the portrait of Kamala Harris on the cover of Vogue. I was thinking about that as you spoke.

AL: What happened with that was, in April 2024, Kamala went out to Arizona and did this incredible speech on abortion. She was on fire. It was amazing. I came into the office the next day and I said to Karen, “We have to photograph Kamala Harris. We just have to do this.” The magazines I work with weren’t ready to take her photograph. They weren’t interested at that moment, but I said, “I don’t care. OK, I don’t care. Call her office. We want to photograph her. I want to do it. Let’s do it.” And it began, and they were really happy. We were trying to work out a time, and then, of course, she got nominated as a Democratic candidate for president. So then it got a little harder to fit in, time-wise. And at that point, Vogue was very interested in doing a digital cover.

We did finally have the session, and it went online in a couple of days. It just went right out there. To me, it’s the beginning of a relationship with her that hopefully I’ll return to when she’s in the White House.

BLVR: That was the first time you’d ever photographed her?

AL: No, I actually worked with her when she was the attorney general of California. I really loved the photographs I did. I did her in the courtroom. How many years ago was that now?

In fact, the best photographs of Kamala Harris being made now are of her on the move. Those photographs—all that work that’s being done while she’s campaigning—are the most extraordinary pictures of her out there, and you really get to see her in action. I love those pictures. I have a different problem, which is: How should she sit for a photograph? No one’s telling me what to do, but I knew she should be serious and accessible. All those things go through your mind. She’s not president yet, you know.

But I’ll tell you that the greatest photography going out right now is photojournalism and the journalism in our newspapers. I am obsessed with looking at The New York Times and The Washington Post to see all the work being done every single day.

BLVR: I can’t help but notice that you haven’t photographed Trump since he has been in office. I am aware you’ve shot him twice in the past: once with Ivana, his first wife; and then once with the very pregnant Melania. You’d talked about the desire to photograph Kamala even before you were commissioned to do so, and I am wondering if that works in reverse—if there are people you don’t want to image?

AL: Well, [the photojournalist] Doug Mills is doing such a great job with Trump. I look at his work every single day, and I admire him so much. He went through the White House years with Trump and now is out on the road; he’s taking care of it for everyone. I also like my photograph of Trump and Melania so much—I can’t think of where else I could go. I did think about photographing him when he was in office. I don’t know. I’m just waiting for him to be all decrepit and squished and in a corner somewhere, to maybe go back. He’s almost there.

III. THE MORTAR BETWEEN PICTURES

BLVR: As someone who has straddled those worlds—the world of photojournalism and the world of editorial work—what is your relationship to the art world? We are speaking on the occasion of your new exhibition at Hauser & Wirth in New York.

AL: I like the idea of working with a gallery, in part because they manage estates; Hauser manages the Louise Bourgeois estate, for instance. I have children, and I like the idea that, after my life, there’s someone there to oversee stuff. And the gallery has never pushed me to do anything.

Bea Feitler, who was an art director I worked with, told me that you need to stop every now and then and look at your work and understand what you’ve done. I’ve said this nine million times, but I’m very engaged in looking back at my work. That’s how you learn to go forward, how you learn what you want to do next. It’s hard to believe, but many photographers don’t do this. They go out and they shoot, shoot, and shoot—especially in journalism—and then they don’t really get a chance to look back at everything they’ve done.

All my shows have always been about chronology. I’ve done books that reflect these chronologies, from 1970 to 1990, 1990 to 2005, 2005 to 2016. I do an edit first; then I do the book. The years from 1990 to 2005 were when I was with Susan Sontag, and it became my favorite book: A Photographer’s Life. It has family pictures, and the assignments were, you know, put together with these photos.

The years from 2005 to 2016 were an attempt at trying to put some portrait work together. I don’t think I’m a very good portraitist. I think I’m OK. So when it’s just by itself, and you don’t have the journalism to kind of knock it back and forth, it can look a little boring. [Laughs] I’m still taking the other kinds of pictures, the more personal ones, for myself. But I can’t publish them, because my children, at a certain point—like ages twelve and thirteen—they said, “Mom, we don’t really want to see our pictures published.” I respected that. And I shoot, I still take pictures of them, but I don’t publish them. My older daughter, when she was going to college, she would call me and we would FaceTime, and I had this whole series of screen grabs of her. It’s really fascinating, because the camera is not there. She’s just talking to this phone, and it’s as real as real can be. They’re kind of amazing pictures of her.

BLVR: The question of chronology is interesting. That has been such an organizing principle for you, as you say, and you’ve strayed from it here, in this show. The very title is Stream of Consciousness.

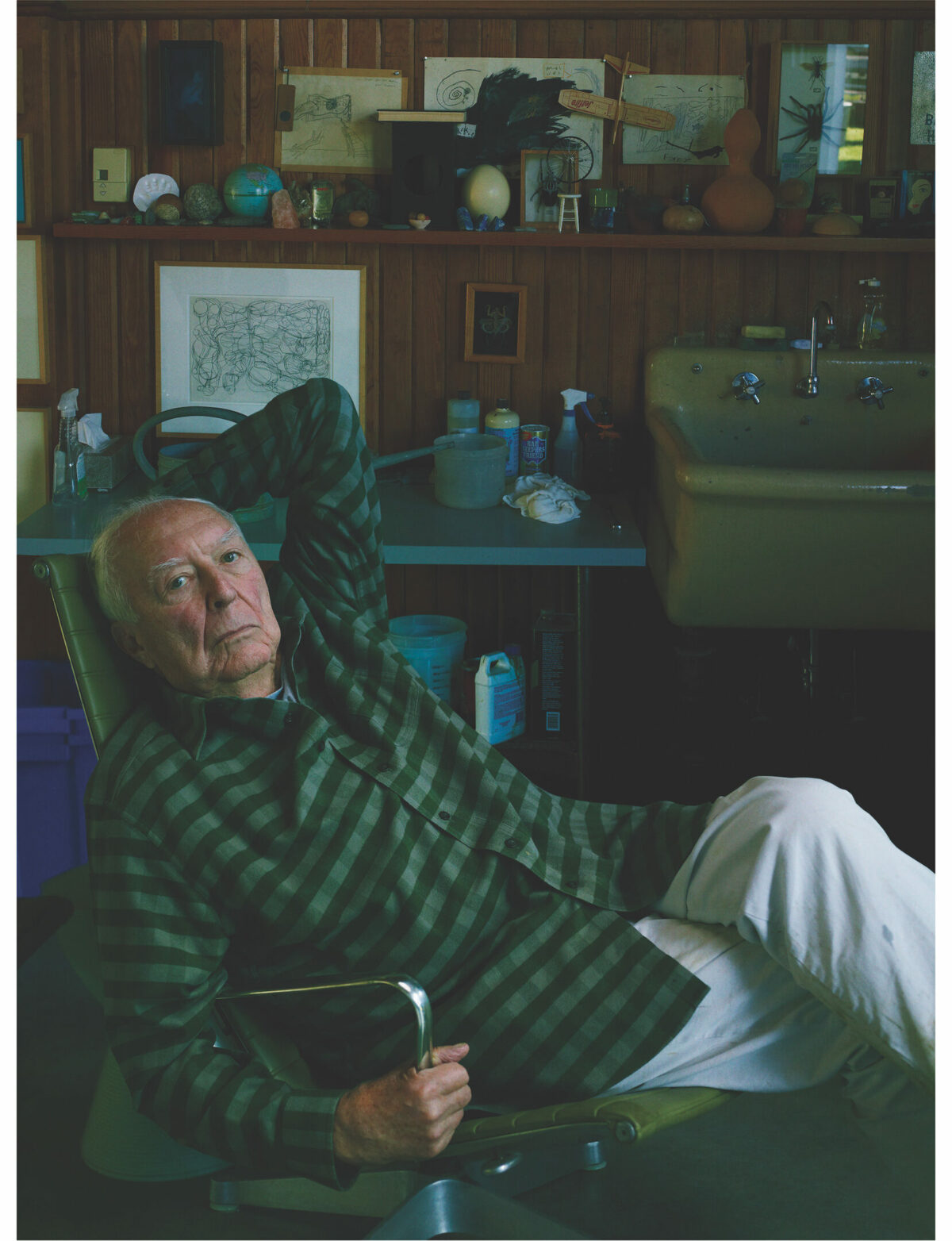

AL: You know, the early conversations around the show were like, Annie, you’re such a contemporary photographer, you should just show your new work. I put up a bunch of things on my work wall, and then I went through everything I had and I picked, like, ten pictures. Every day I would go by and look at the wall and at all the work in the last few years, and I finally said, I’m just going to pick my favorite pictures. I don’t care what year it was done in. I’m just going to start picking the pictures from the last ten years that really mean something to me. It was the first time I’d done this out of chronology, out of time. I actually really liked it, you know? It was an interesting exercise. I’m still more interested in history and chronology, but it was great to break away from putting things in order, which is the way I’ve been doing things my whole life.

BLVR: Maybe this goes against what you’re saying, that you were just responding to what was jumping out at you. But I will say that I noticed a thread between some of the kinds of pictures and subjects. Among your picks are a lot of artists and writers and creative visionaries—people like Patti Smith, Kara Walker, Amy Sherald, Cindy Sherman. Do you think there’s a thread there? It didn’t strike me, for instance, apropos of the earlier questions, that there were a lot of politicians…

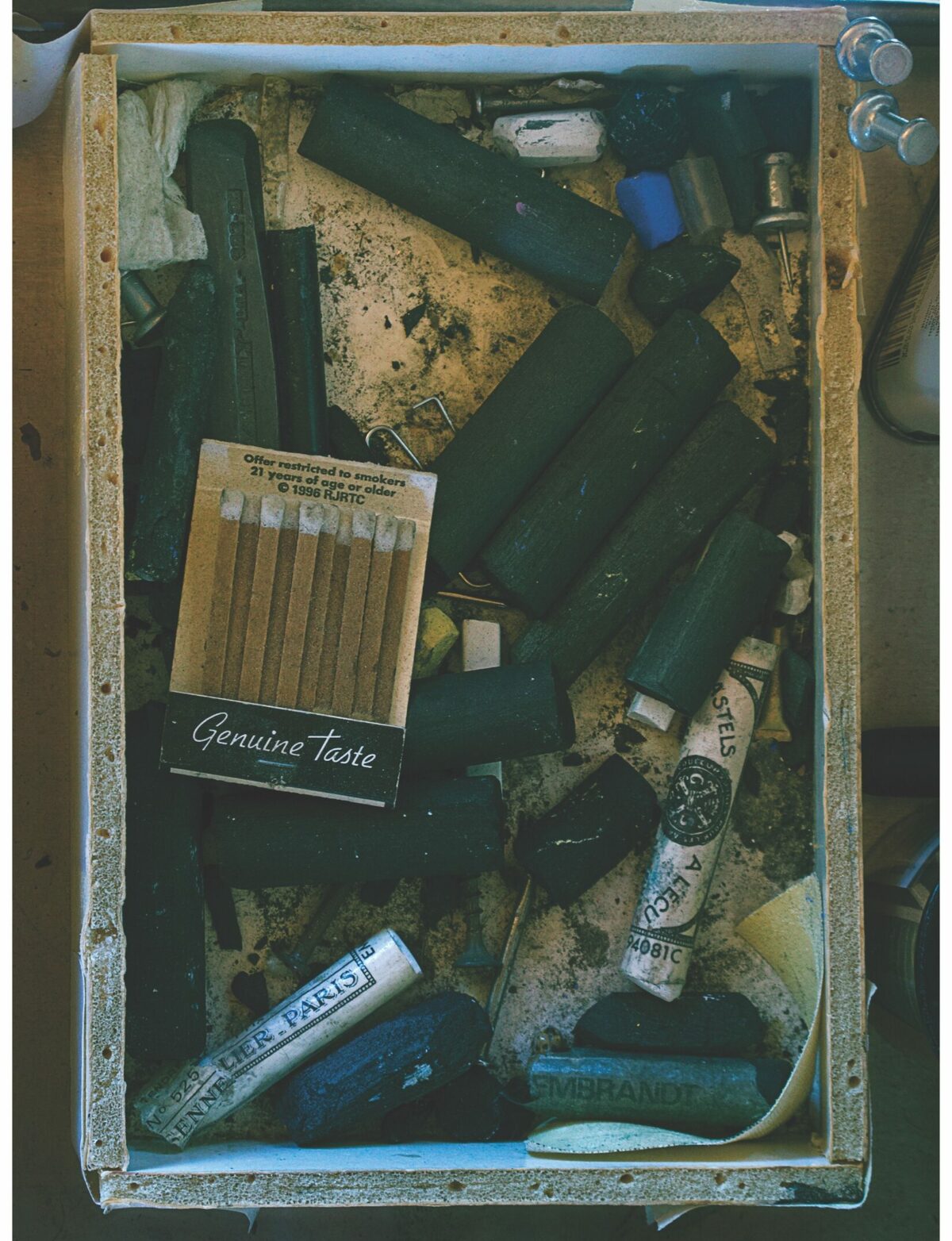

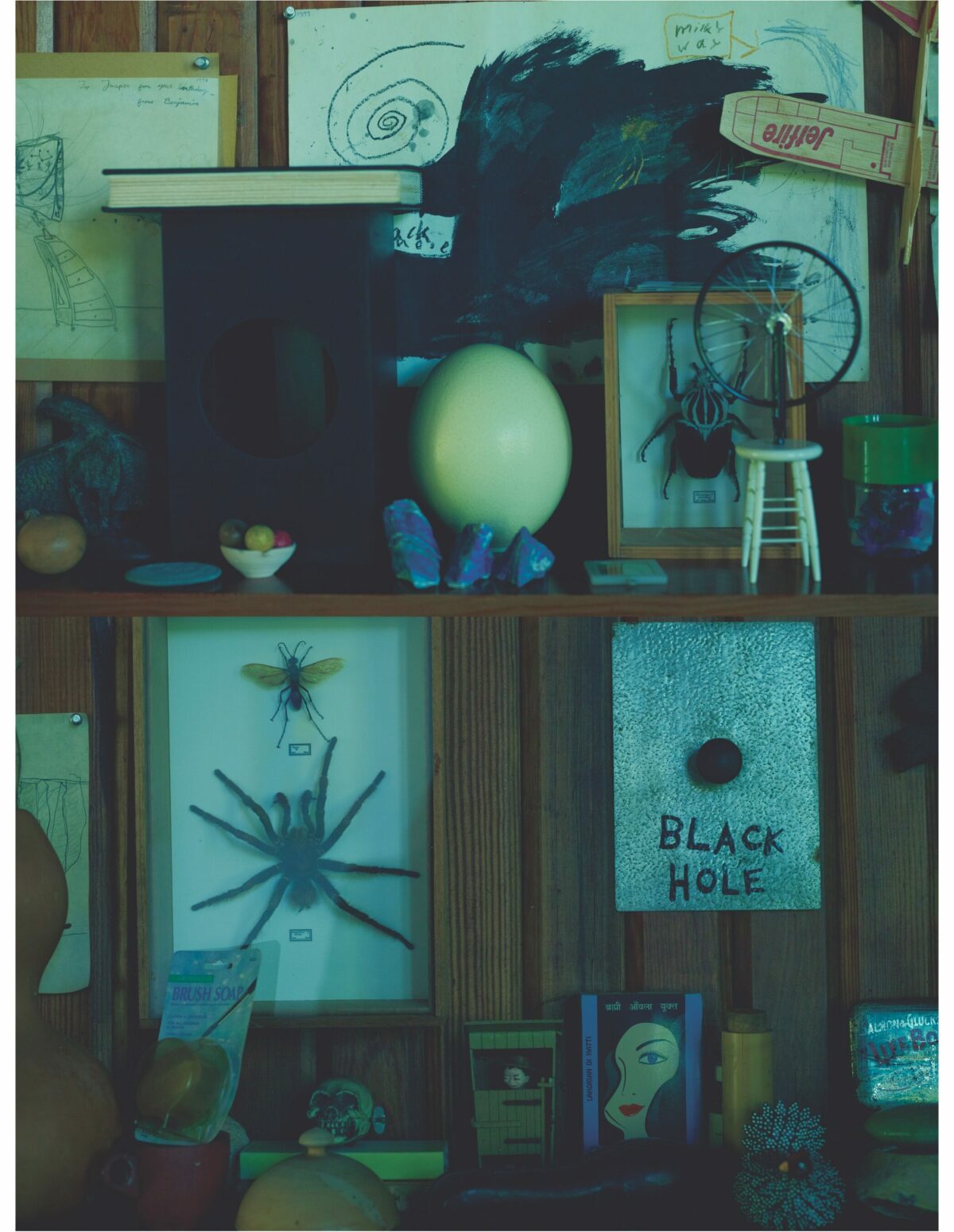

AL: Yeah, people commented early on that I have a lot of artists, that I could do an all-artists show. But the truth is, I’m just fascinated with photography as a subject and the process of how it all comes together. I just love process more than final things, you know? And I love these people. I admire them so much.

The other thing that’s in there is this work I did in this book called Pilgrimage, which is all photographs without people in them. That work has turned out to be the kind of mortar between my photographs. There are quite a number of those pictures here. I am remembering a moment when Gloria Steinem had a fundraiser for Kamala Harris at her house. When I walked into her kitchen, I saw that she had my photograph of Virginia Woolf’s desk on her kitchen wall. I was so moved by that. That was like it, you know? These person-less pictures—there is one of Edward Hopper’s house that he was born in—they kind of hold things together.

BLVR: But all these pieces strike me as being such a different world than making pictures for a magazine, let’s say. And I’ve heard some ambivalence in the last hour about how you approach it.

I am thinking about how the photographs you took inside the Frick Collection [in New York] operate this way as well. These pictures open the Hauser & Wirth show, right?

AL: Yes, they’re at the beginning of the show: I ran a suite of four pictures of the Frick from the ceilings. Annabelle Selldorf—do you know who she is? The architect? She designed the Hauser & Wirth building, though I am the last person to find out about that. Annabelle is a really interesting architect. She was working on redesigning the interior of the Frick recently. Vogue was doing a story on her, and they asked if I would photograph her. I went up to her place in Maine. She was standing looking out at the at the ocean and she said, “I’m trying to figure out what the color of clouds is.” I stood with her there as she tried to figure it out; she thought she would paint the ceiling of the museum’s auditorium that color.

I ended up going to the Frick with Annabelle. This was problematic because the Frick didn’t want me inside, because they had an exclusive with another publication. But Annabelle said, “You’re coming in.” I had only my phone with me; I shot with my phone. I just took a few frames and then walked out and then went back to my studio and studied the photographs. They were so cool, these photographs and the ceiling—the way it looked. Annabelle, whom I think of as always doing straight lines, was dealing with curves in this ceiling. And Vogue eventually ran two of them. I couldn’t believe it. Photos from my camera phone; I couldn’t walk in there with a real camera. My camera phone is amazing. It’s not good for everything, but it’s very good. If you use it horizontally, the sides get all cuckoo.

But that’s when I thought about Stream of Consciousness. That’s when the story about process really took hold. At the beginning of the show, I tell the story of Annabelle Selldorf.

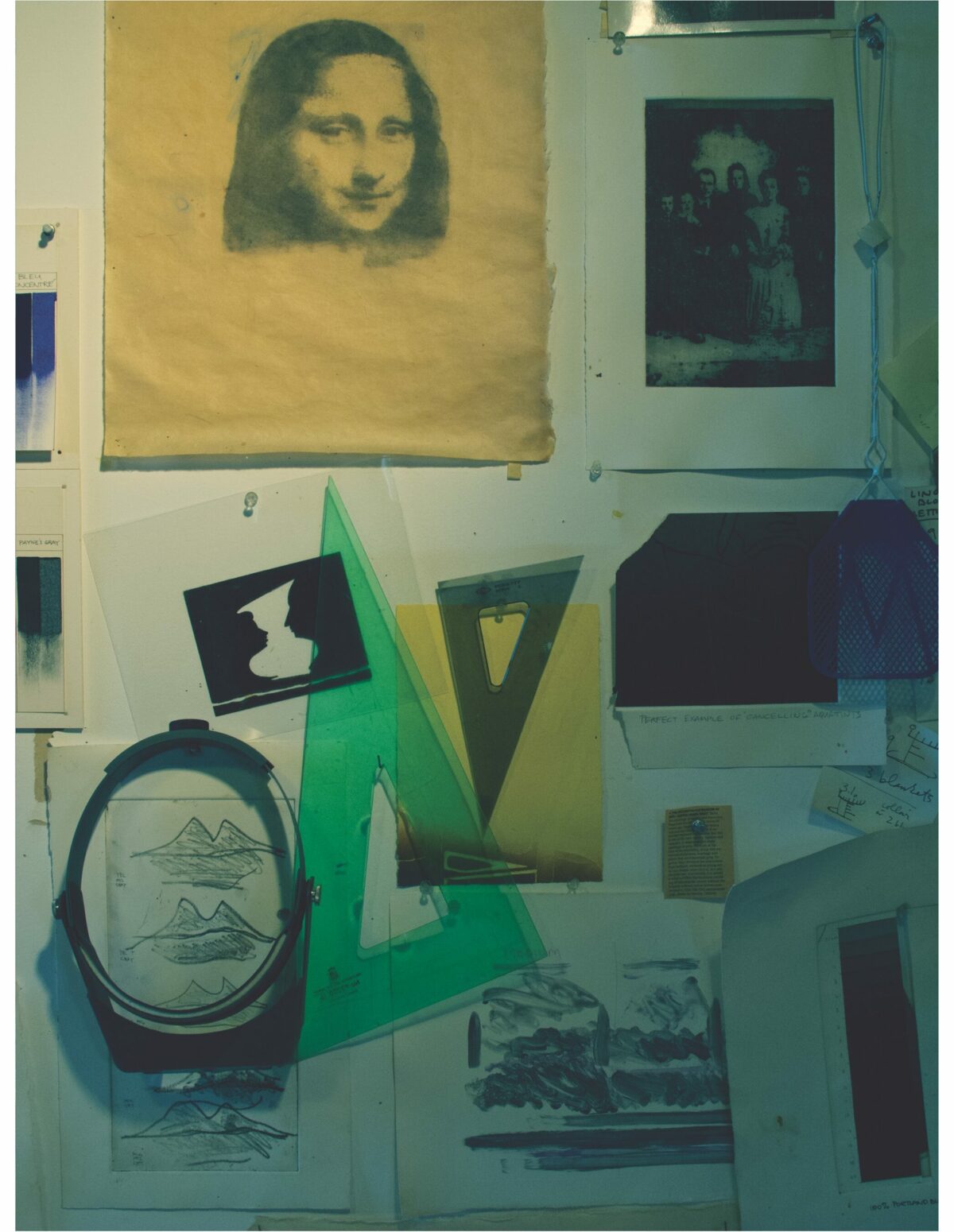

BLVR: You know, I live in Columbus, Ohio, and I saw your show at the Wexner Center for the Arts in 2012. I’ve never forgotten that wall, with the bulletin boards and all the little prints, which I assume was meant to mirror your studio wall. In my mind, it was made up of all those shitty printouts, which I loved.

AL: Xerox-machine prints, yeah. It was the best part of the show, that wall. And I return to that wall repeatedly for ideas.

BLVR: That is interesting that it was also your favorite part of the exhibition. I felt that piece was a super generous way to share your work with an audience. To allow us access to process. We’re able to step in and maneuver between the pictures.

AL: That’s what I admire about your work—what you’ve done, you know, like the way you let the photos be there together. I really like what you’re doing; I think it’s a great way to work.

BLVR: That is very kind. Maybe that is a good place to end—on generative process, and on the space between pictures. Or rather, the way they relate to each other.

AL: That sounds good. I am sorry there was so much rescheduling in making this happen. I know you have two young kids, and I was worried about how that might affect you. By the way, you look exhausted.

BLVR: You sound like my Jewish grandmother! She used to say that to me as a greeting.

AL: Yes, it’s a Red Badge of Courage.