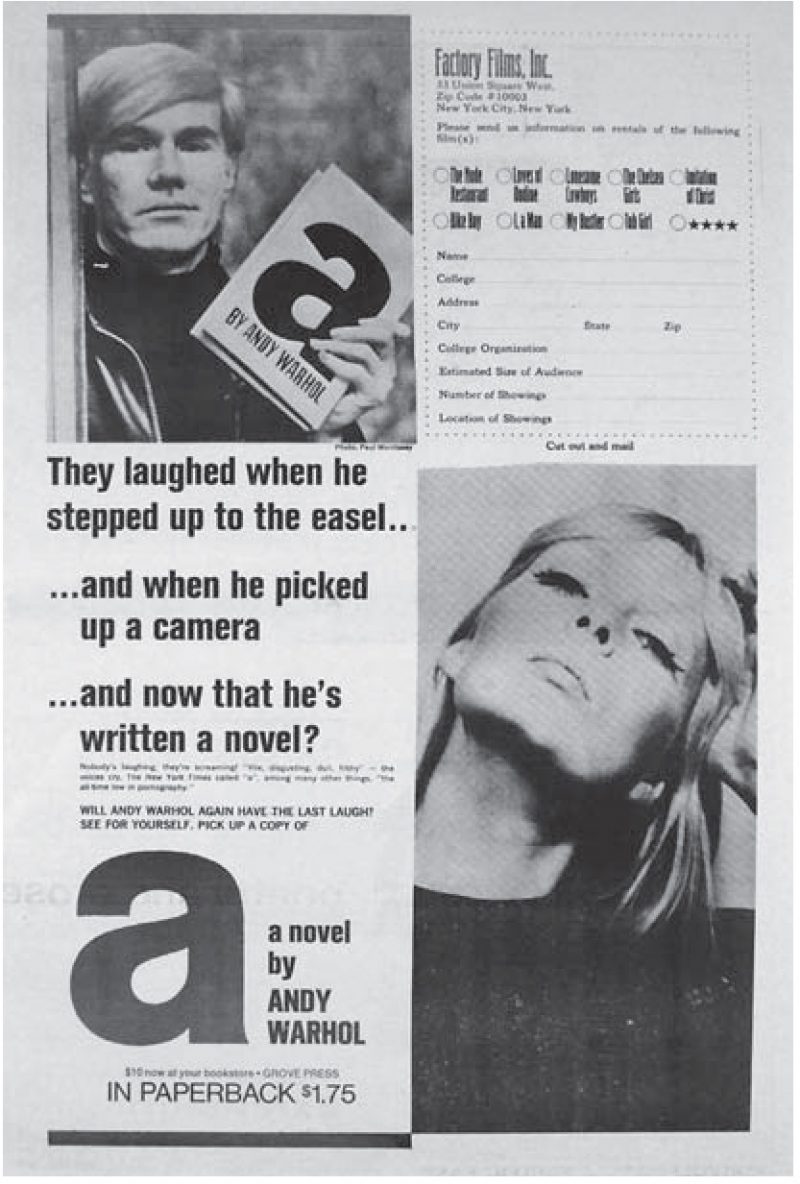

Arnold Leo moved to East Hampton and became a commercial fisherman about forty years ago, having burned out from his intense life as an editor at Grove Press in the late 1960s. He was introduced to publishing as a college intern at Popular Gardening magazine. He was the only male in an editorial office full of young women, and his internship involved many martini dinners and the loss of his virginity. This turned out to be good training. At Grove, Leo would copyedit the works of the Marquis de Sade and Samuel Beckett, as well as anonymous Victorian porn lit. He was also the editor of Andy Warhol’s notoriously unedited a: a novel. But once Grove Press went nearly bankrupt, and the big corporations that sell frozen dinners started to buy up American trade publishers, Leo left the industry.

—Lucy Mulroney

THE BELIEVER: How did things begin with Andy Warhol and Grove?

ARNOLD LEO: Well, I was working on a variety of projects, and one day I just happened to notice in the general editorial files that there was a file for Andy Warhol. I took a look, and it was a file that had been created after the owner of Grove Press, Barney Rosset, had agreed to publish a novel by Andy Warhol. It was known that almost anything Andy produced was an immediate commercial success, whether it was his artwork or the movies. So I see this file and I think, Why is nobody doing anything about this? My immediate boss was Richard Seaver—he was an extremely intelligent and gifted literary person—so I said to Dick, “Look, if nobody wants to do anything about this Warhol novel, could I maybe get it moving?” Dick said, “Yeah, go ahead.” Of course, when the socalled manuscript came in, it was this incredibly badly typed jumble of transcripts from tape recordings. The girl who was typing everything at the Factory was named Pat…

BLVR: Pat Hackett.

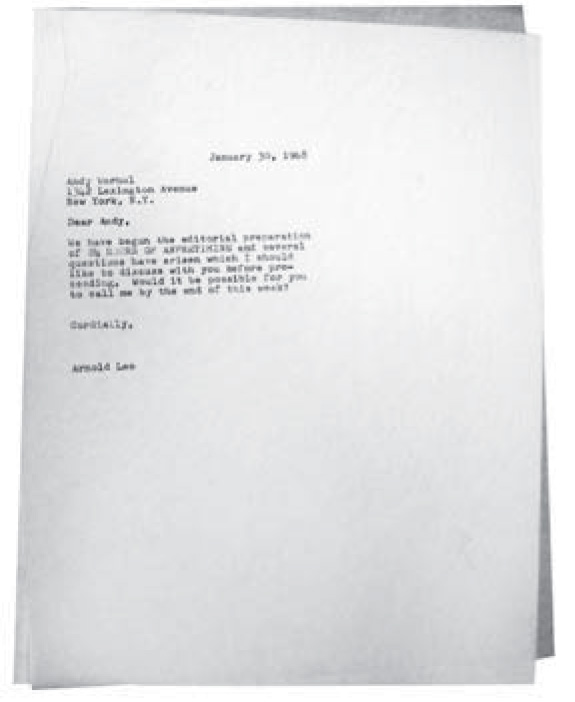

AL: Yeah. Every time I went to the Factory, here was funny little Pat Hackett typing away in a little cubicle. I mean, she was like this slave they had, doing nothing but typing religiously, day in and day out. She was still an undergraduate at Barnard at the time, and she would come to the Factory after school a few days a week. But the girls who transcribed most of the novel were Cathy Naso and Iris Weinstein and this girl Brooky, whose last name we don’t know. They wandered into the Factory one day looking for Gerard Malanga, and they were wrangled into transcribing Andy’s novel. Maureen Tucker and Susan Pile helped, too. Anyway, so I take a look at this manuscript and I say, “Oh my god, this is the worst mess I’ve ever looked at, this is going to be a colossal job straightening this out.” The first thing I do is I write to Andy, “Could I meet with you about this? We’ve begun the editorial process to publish your novel.” So a meeting was arranged, and Andy came, and Billy Name. So I said, “Well, look, I’m sure this will be worthwhile to publish, but there are just so many problems in this transcript, spelling and trying to identify who’s speaking and where the locale is. Maybe we’ll have little footnotes or something to help the reader along here.” Billy Name and Andy were saying, “Oh my god, we can’t! Why do we want to correct all this? Isn’t what makes it real is that all these mistakes are here?” It wasn’t just the recording, but also the typing. “The manuscript should be reproduced the way it is. And that will save us all a lot of time.” That was a big concern, really. Mind you, I was an extremely careful editor…

BLVR: What a mess a would have been!

AL: The manuscript was the worst thing I’d ever seen! But here were Andy and Billy Name saying, “But isn’t that part of the charm? That’s how life is, there are lots of mistakes. It isn’t perfect. It would take too much time to try and straighten this all out. Let’s just tell the printer to print it exactly as it appears in the manuscript.” It took me a bit to absorb that as an idea that had any merit, but suddenly a light went on. I began to see what Andy was about, you know? It was like the characters he would bring into his movies. He didn’t care how imperfect they were, or how much they wanted attention and were willing to do anything to get it. That was the reality, you see. It was reality that fascinated him. So we had a discussion about how we would do the typesetting, because it occurred to me that it was very long, and that it might be easier for readers if we set it in two columns on a page, rather than running a full page of text.

BLVR: So you came up with the three styles that the novel is formatted in?

AL: Yeah. I remember feeling that if it was set as a block of type on a page, it would be extremely hard to read. You know, people would not want to bother trying to wade through it. So I came up with Style A, Style B, or Style C. I said to Andy, “Here are a couple of techniques where we could assist the reader,” and, in typical fashion, Andy said, “Oh, well, they’re all nice, let’s use all of them.” Billy Name and I were meeting pretty often to go over editorial issues…

BLVR: Like what?

AL: Well, there was a bit of a fear that some of the people who appear in the text would want to be paid, so it was decided we would use initials and different names. Andy became “Drella,” and—

BLVR: Edie is “Taxi,” Brigid is “the Duchess.

AL: But most of the people connected with the Factory were just glad to get the publicity. Attention was what they craved, so it’s not too likely that we would have had very many lawsuits. But the publisher’s point of view was “Let’s not take a chance here.”

BLVR: What did the art department do to the manuscript?

AL: So the printer did his best to reproduce the garbled mess, and the galleys came back and, of course—being still, at heart, a very meticulous editor—I instructed the proofreaders to read the galleys against the manuscript and make sure that every mistake in the manuscript was faithfully reproduced in the galleys. But Andy and Billy Name said, “Wait, no! Any mistakes the printer made, that’s fine. It doesn’t matter. The printer’s got a right to make mistakes as well.” By this time my meticulous editorial inclination has been completely unhinged, and I’m saying, “You’re right, let’s leave them in there.”

BLVR: The novel’s supposed to be twentyfour hours in the life of Ondine…

AL: We all knew that it was twenty hours, maybe not even a full twenty hours, but everybody was saying it was a day in the life of Ondine. The original title was 24 Hours, but Andy didn’t like 24 Hours. a, of course, basically meant “amphetamine,” because Ondine and Billy Name and some others in that group, they were all extreme amphetamine users.

BLVR: So where did the “a novel” come from? Like a: a novel?

AL: I’m not sure. The idea was that this is how the modern novel should be created: be utterly realistic, nothing is dull, every moment of life is significant. But it’s not a day in the life of Ondine; this is a work of art, a novel. It’s a completely weird work, but in a way it is a novel, because those characters in it were constantly creating themselves as characters. That’s why they all had names like “Rotten Rita.”

BLVR: I wanted to ask you about Helen R. Lane. At the Grove Press Records, I found a reader’s report written by her about Warhol’s novel.

AL: Helen Lane was a very talented literary person. She was also a brilliant translator.

BLVR: Her reader’s report is better than anything I can write.

AL: She was a pleasure to work with. She was so intelligent. So what did she say about a?

BLVR: She says:

In this work… Andy Warhol… undermines the traditional shape of the fictional narrative, as he has hitherto sapped our traditional ideas of mimesis in painting, sculpture, and film, for A Novel consists solely of a typewritten, word-for-word transcription of an eight-hour tape recording made when Andy and a friend got high on 50mgs of Obertrol. …If bone-deep ennui has become the very warp and woof of our automated era, he has become its most wholehearted prophet… Every era has seen the production of types of realism that were both denied as art and deemed dangerous to the sensibilities of the average man. From Victor Hugo’s vulgar “Quelle heure est-il” in Hernani to Zola and Joyce, critics and readers alike have raised the cry of “utter formlessness” and “destruction of the very fabric of society.” This book is sure to raise the same howls, for it too seems purposeless and contentless by ordinary aesthetic standards, and its characters are so blatantly queer as to arouse unconscious hostility in almost any square reader.

AL: Please send me that. Helen was so… god, was she intelligent.

BLVR: So you weren’t worried about a being censored at all?

AL: Oh, never. If they couldn’t stop the Marquis de Sade, they were not going to stop a. Is it the greatest literary work ever? No. [Laughs] But it is something of cultural value. It just fit in with everything that Andy was doing. It was a time when a lot of preconceived and very restricting assumptions and values were really being ripped apart. While there was a certain amount of destruction in the process, it was also liberating and necessary to allow healthy growth. In a way, a might be seen as one of those kamikaze attacks on the culture that’s meant to shake people to a realization of what reality is and what beauty is and what is of value in life.

BLVR: Well, I really enjoyed the book. I enjoyed reading it.

AL: Well, you have a great deal of patience, then.