Charles Burns is one of today’s most dramatically talented cartoonists. His comics can be funny and creepy, but they always feel trenchant, and textured, in part because he brilliantly inhabits genres like the romance, the horror story, and the detective story without simply rejecting their conventions or ironically reversing their concerns. This tension in his work seems to mirror his obsession with the relationship between external and internal states of being, surface and depth (which we recognize, say, in the theme of “teen plague” that he’s returned to throughout a decades-long career).

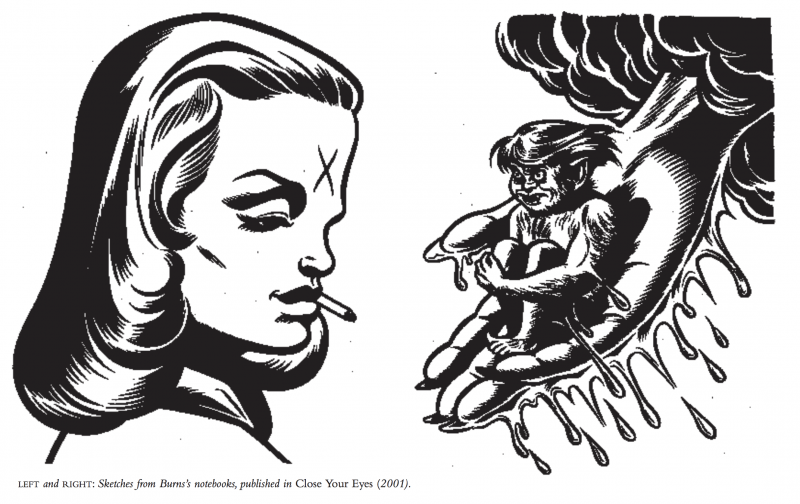

Burns gained a following in the avant-garde comics magazine RAW in the early ’80s, and he’s since published numerous book collections, including Big Baby in Curse of the Molemen (1986); Hard-Boiled Defective Stories (1988); Skin Deep: Tales of Doomed Romance (1992); Modern Horror Sketchbook (1994); Facetasm, with Gary Panter (1998); Big Baby (2000), and Close Your Eyes (2001). In addition to prolific illustration work for venues such as the New Yorker and this magazine, his range of projects over the years has included designing the sets for Mark Morris’s restaging of The Nutcracker (renamed The Hard Nut) and contributing to MTV’s Liquid Television, which created a live-action series based on his character Dog-Boy.

Burns may be most famous, however, for Black Hole, a twelve-issue comic-book series that made my life—and plenty of other people’s—that much more interesting from 1995 to 2004. Black Hole takes place in Seattle in the 1970s, focusing on a group of four teenagers who all get “the bug,” a fictional STD that deforms them in different ways. Rob grows a mouth—complete with teeth—on his neck; it speaks when he’s sleeping. Chris sheds her skin. Keith develops tadpole-shaped bumps on his torso; Eliza sprouts a tail. Black Hole’s precise black-and-white images are gorgeous and frightening at once; the rich narrative is dark without being despairing. Since the graphic-novel version appeared to acclaim in 2005, Burns has published a book of photography, One Eye, and completed a segment of an animated feature film called Peur(s) du Noir (Fear(s) of the Dark). His graphic novel in progress is, dizzyingly, about both punk and Tintin. I visited Burns, who lives in Philadelphia with his wife, daughters, and black cat, Iggy, at his studio in October. Not only is he a masterful draughtsman, but he makes an excellent cup of coffee.

—Hillary Chute

I. COVERS

THE BELIEVER: How did you start working for the Believer, anyway?

CB: It was out of nowhere, just an email or telephone call. From—god, who did call me?

BLVR: For this ongoing project, for years and years…

CB: Initially I thought, Oh, I’ll do a cover. They said, “No, you’ll do the cover every issue.” I’m slowly learning to draw every human being in the United States. Occasionally there’s a situation where there’s only one blurry photograph that exists for reference and so I’ve got to use a lot more of my imagination to come up with a portrait. But generally speaking there’s enough information to do a fairly accurate photo-representation, a photorealist cartoon.

BLVR: Has there ever been anyone who you’ve really disliked having to draw?

CB: Occasionally you have someone who you admire and respect, but maybe they’re not handsome or beautiful. But there’s nobody that I thought, like, Oh this idiot…

BLVR: “Fuck, I have to draw so-and-so….”

CB: Oh, actually, that has happened, but I won’t mention who that is.

II. ILLUSTRATION WORK

BLVR: Tell me about some of your recent commercial work.

CB: Recently I did illustrations for Cartier.

BLVR: The diamond jeweler?

CB: Well, I was in France. This is a campaign for a watch.

BLVR: Wow. You had to draw a Cartier watch.

CB: Yeah, yeah. It was an odd thing that just came in. There are people in the commercial world who are only aware of my illustration work. And then, I would imagine, there are people who read the Believer who just know, “Oh, he’s the guy who does the covers for the Believer,” and have no idea that I do comics.

BLVR: Have you had a favorite and a least favorite illustration project?

CB: You can never say least favorite, because you always want new jobs. But favorite? I did a bunch of things for Altoids. That was actually genuinely fun. As part of the ad campaign I was supposed to draw three comic strips and I said to the art director, “Are you sure that you want me to do this? I mean, this has been OK’d?” I couldn’t believe that all of it had been OK’d. There were billboards of a giant tongue sticking out with a stiletto heel poking through the tongue.

BLVR: It wasn’t a supersanitized commercial.

CB: Yeah, very, very odd. So I didn’t have to worry about: is this OK, or is that OK? I was just told, “Draw two wires electrocuting a tongue!” But out of the comic strips that I did for them, there was one that was never released. At the very, very, very last moment the head honcho in charge decided we couldn’t do it. The campaign was for Altoids breath strips that are supposed to be really hot and intense—they’ll burn your tongue because they’re so strong. So in the comic there’s a kid who’s got a magnifying lens and he’s burning ants, then it builds from that and he’s going out and burning larger animals like a pig and a cow. And in the end, there’s the big payback when he samples some Altoid strips and he’s imagining a gigantic magnifying lens burning his tongue as all the animals he’s tortured stand around and laugh at him.

III. CHILDHOOD—GENEALOGY

BLVR: Were you into drawing as a kid?

CB: Yeah, before I could write, I was drawing. I think a lot of it had to do with finding some way of entertaining myself. And finding some kind of internal world that I could climb into and work inside of.

BLVR: What was high school like?

CB: High school was like… There’s a book I did— called Black Hole? [Laughter] No. High school was much more benign than the way I portray it in Black Hole.

My family moved around a lot when I was growing up, and drawing comics was one of the things I got attention for—I may have been socially inept, but I could draw good monsters. And I would kind of force my friends to draw with me. In grade school I would force my friends to do parodies of superhero comics, and then by the time we were in junior high school, we did parodies of underground comics. And Seattle was conducive to staying in and doing artwork, because it was raining all the time….

BLVR: What work did you like?

CB: My family went to the library once a week and came back with stacks of books, including art books and collections of classic comics. My father had copies of the reprints of Mad when it was a comic book by Harvey Kurtzman, and I was looking at those before I could actually read and understand what the stories were all about. That had a big, big impact on me. Another thing that had a big impact was Tintin. In the late ’50s and the early ’60s an American publisher tried putting out a series of Tintin books, and my dad bought those for me, so I was lucky enough to grow up reading Tintin.

And then as I was growing up I’d read whatever I could find, which would include all of the major, mainstream superhero stuff. And by the time I grew disinterested in that, there were underground comics, which kind of saved me.

BLVR: Where did you buy them?

CB: Well, at that point even though they were supposed to be for adults, you could walk into any head shop and the guy that was selling you your hash pipe was more than happy to, you know, take your fifty cents for Big Ass Comics #2, which smelled like patchouli oil. You’d walk into this kind of dungeony head shop and look at their wares, and they’d have huge stacks of every underground comic available. I would always go for the Robert Crumb books. It’s hard to explain what an impact his work had on me.

I was really interested in comics, but had reached a point where I was fed up with all the superhero stuff. And here was this guy who had grown up reading some of the things I just mentioned, like Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad, and other mainstream comics, and he’d come up with something that was incredibly personal and strange, and yet harkened back to classic comics of another era.

Actually, the first thing I saw of his was a greeting card, because he used to work at American Greetings Corporation. And I remember that although it was a sweet, saccharine sort of birthday card, it was still— there was something in there that just seemed kind of strange and wrong. When I found a copy of R. Crumb’s Head Comix at our local bookstore, I realized it was the same artist.

BLVR: So you always knew you wanted to do comics professionally.

CB: By the time I was in high school I was producing pieces that were not reliant on a traditional narrative at all; they were influenced by things that were in Zap, by Crumb and Victor Moscoso and Rick Griffin. I was trying to do pieces that looked professional—that looked like “real” comics. I would get library books about cartooning that would tell you what kind of pen and paper to use. I researched all the technical aspects of creating work for reproduction, and got the right tools and did my best to learn how to draw with India ink on illustration board.

The funny thing is I never really thought about it in terms of “professionally.” I thought maybe I’d eventually get published in some underground comic or something like that, but really I was creating without an outlet.

BLVR: You were taking it so seriously, but it wasn’t goal oriented.

CB: It wasn’t at all.

So when I was done with high school I went to college and took art classes. I had this naïve sense that I’d go to art school and something would magically happen and I would become an artist and I’d have a career. I started out at the University of Washington majoring in printmaking because that somehow seemed closer to what I was interested in than painting or sculpture or design.

In the meantime, while I was taking all of these fine-art classes, I was doing my own work on the side. I’d come home and work on comics. Every once in a while I’d bring them in to show my teachers but never got much of a response. It was never met with derision or contempt or anything like that, but they just didn’t really know what to say about it.

Eventually I started getting comics published in the school paper when I was at the Evergreen State College.

BLVR: You went to Evergreen? I thought you went to University of Washington.

CB: Well, I went to three colleges, because I was bouncing around. I went to University of Washington, and then I went to, I think it’s called Central Washington University in Ellensburg, and then I went to the Evergreen State College and was classmates with Lynda Barry and Matt Groening.

I was there for a year, maybe a year and a half, something like that. I was working on the paper, doing comics parodies…. [Looking through binder of college work] Here’s one I did of The Family Circus: it says, “Shut the fuck up, Mommy, we’re trying to watch TV!”

IV. EARLY WORK

BLVR: Outside of the Evergreen paper, where did you first publish your work?

CB: I had a comic called Mysteries of the Flesh that was in a punk tabloid put out in the Bay Area called Another Room. There were a few other things before that, but not much.

BLVR: [Looking through binder of Burns’s early work] Wait. Can I turn back here? The mouth on the body…. it’s like in Black Hole, where the character Rob has a mouth on his neck.

CB: It’s pretty clear that all this stuff has been in there from very, very early on. One of the episodes of is about a guy who orders a pair of “X-Ray Specs” from the back of a comic book and they actually work—he can look under his skin and see more than he wants to. When his girlfriend walks in he loses it.

BLVR: How did you start publishing in RAW?

CB: I was out of school and living in Philadelphia, going up to New York, showing my little meager, sad portfolio around.

BLVR: Why meager and sad?

CB: It was that catch-22 where to get published, you need to be published, and at that point I just didn’t have anything. So I was showing photocopies of my comics and things like that.

It was horrible. You’d call up whatever magazine and ask, “What is your portfolio day?” And you’d find the address, and there’d be a nice secretary out there: “Put your portfolio over there in the corner.” And later you’d always try to figure out whether anyone had actually even touched it.

BLVR: Did anyone ever get back to you?

CB: At that point? No. Never. Well, actually, in Philadelphia, I got my first commercial job, for a nursing magazine. So I did nursing illustrations.

But I was up in New York and I saw the first issue of RAW, and there was an address listed and the line “We’re interested in submissions.” So I figured out where Greene Street was and rang the doorbell. And a frenzied Art Spiegelman came to the door: “What? What? What do you want?” And he basically told me to send Xeroxes of my work, and then got back in touch with me, and we met. He was the first cartoonist I ever talked to. And he was the first person who really figured out what I was trying to achieve.

BLVR: And then your pieces started appearing in RAW.

CB: Right. In 1981 they published an abstract piece [“And I Pressed My Hand Against His Face, Feeling His Thick Massive Lips, and…”] and Dog-Boy.

BLVR: Where else was your work published?

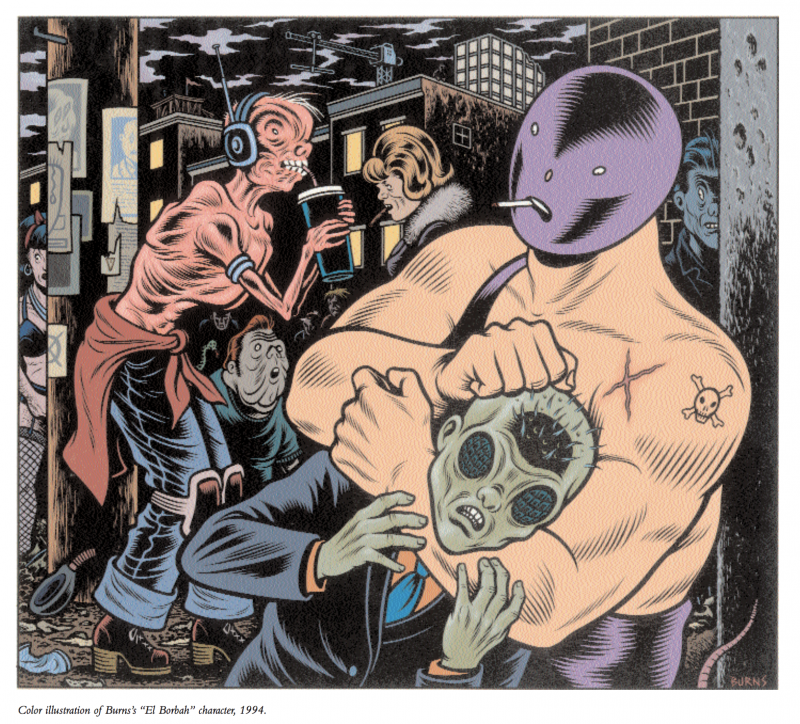

CB: RAW was the first significant place. There weren’t that many places for work like mine to appear. There were mainstream comics—Marvel Comics and DC Comics—which I had never had any interest in at all. As for underground comics, there were still a few titles coming out, but hardly any of interest. There was National Lampoon, and they had a comics section in the back. And then there was Heavy Metal magazine, which republished a lot of French science fiction, fantasy, so-called “adult” comics, and I eventually managed to get published there. I got my character El Borbah serialized in that.

V. BOOKS

BLVR: Those El Borbah pieces were collected as your first book, right?

CB: Yes, the pieces that came out in Heavy Metal became a book.

BLVR: In terms of style, and also in terms of the content, how would you describe your work at that time?

CB: There were certain kinds of stories that I liked. I was reading a lot of romance comics, older romance comics from the ’40s and ’50s. So “A Marriage Made in Hell,” which I did for RAW, takes the structure of a typical romance comic and turns it on its head. But I had a genuine affection for those stories—I actually liked reading them—even though it’s hard to describe why that was. It wasn’t just because they were kitsch, or “so bad they’re good.” I liked playing with all of the romance-comic conventions, but I was also stepping back and thinking about the male and female stereotypes found in all of the stories.

I was also interested in detective stories. In my El Borbah stories I came up with this ridiculous detective who pretty much solves all of his cases by accident.

BLVR: How did you come up with the character?

CB: I lived in central California for a while and had access to stores where migrant workers came that stocked Mexican comics and magazines, including wrestling magazines, which I loved. There were amazing costumes and ridiculous characters. One of my favorites was a masked wrestler who dressed like an executive—he had a suit and tie, and he’d arrive in the ring with his briefcase.

So I combined my love for costumed wrestlers and hard-boiled detective fiction and came up with El Borbah.

BLVR: What was your next book after El Borbah?

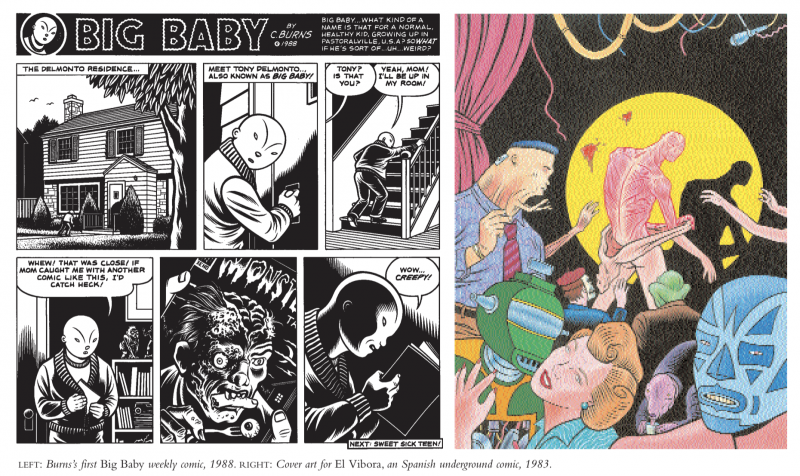

CB: There was a collection of little hardbound books, around thirty-two pages, which were put out by a Belgian publisher. I like thinking of a book as an object in itself, and I really loved those—a hardbound book with a cloth spine, just this nice object. I started working on a book in that series, but it didn’t work out. Eventually I did a book in a similar format with Art and Françoise [Mouly] called Big Baby.

BLVR: How did you get interested in the Big Baby character named Tony?

CB: In a way, he’s probably just a stand-in for myself as a kid growing up in the early ’60s. He’s a kid who’s examining this very confusing adult world and trying to make sense of it and interpreting it as best he can. He’s also got an overactive imagination that gets him into trouble sometimes. And he’s also this little kind of mutant kid who’s off in his own world.

BLVR: The suburbs in Big Baby are presented so creepily.

CB: They’re a reflection of the typical American dream-home world from that time period. I lived in places that were similar to that—not typical suburbs but close enough. It was what was presented in Better Homes and Gardens, or whatever those magazines were, where you’d leaf through and see all the products and the food and the abundance of everything. I was always interested in that facade of the American way of life, and what was hidden behind the facade. And that’s what the first story deals with: monsters on TV—the fake things on TV— and then the real monster that’s living next door who’s beating his wife. A kid coming to terms with made-up television horror that’s kind of fun to watch, and the reality of abusive adults that’s not so fun.

BLVR: That kind of tension is part of some of the stories in your book Skin Deep, too.

CB: Yes. There’s a story in there called “Burn Again” that deals with a kid who has a father who brands an image of Jesus on his chest and tries to pass it off as a miracle. God finally comes down and straightens everything out.

BLVR: So when did you start Black Hole as a continuing comic book?

CB: In the early ’90s.There were a few pieces I had done before that that were similar. There was a Big Baby story that was in Skin Deep that deals with the whole idea of teenagers afflicted with some kind of disease that marks them, some kind of teen plague. And then there was a one-page piece in RAW that dealt with similar ideas. But actually the way that I had originally started Black Hole was having teenagers who die and then come back. That was the first way I was thinking about it. And the piece in RAW dealt with dead teenagers coming back and wandering into their parents’ houses late at night and going through the motions of what their former lives were, like watching television and making sandwiches.

I have pieces from the late ’70s that deal with the same kind of subject matter—some sort of disfiguration, some kind of disease that’s afflicting teenagers. So that was a recurring theme that I was obviously interested in, something I hadn’t fully explored. I was also at a stage in my life where I really wanted to involve myself in a much denser narrative. I realized that I had a long story to tell, and started serializing it in comic form.

VI. BLACK HOLE

BLVR: Why do you think the whole disfigured-teen-with-the-veneer-of-normalcy thing has been an ongoing theme?

CB: It goes back to the idea of a facade—presenting something on the surface and then having an internal world that’s different than that. Someone can look very normal on the outside and just be boiling up inside with something dark and ugly. And the idea of the teen plague is a physical manifestation of whatever is going on internally: the turmoil that’s going on inside manifests itself in a way that forces the characters into a much more extreme situation.

I don’t even know if it’s actually true, but I’ve always said that I could tell a similar story without the concept of a teen plague. But for me, it was interesting. I liked being able to deal with that particular subject matter. I like the idea of a girl slipping out of her skin, or anyone slipping out of their skin. I could show you drawings I did in the early ’80s of someone doing a striptease and taking his skin off. There’s even a RAW ad I did where the character has got a skin that’s stuck up on a hanger, and he is lying in bed with his raw flesh revealed. So that whole idea has certainly been with me a long time. I like playing with that kind of imagery, thinking about how a snake molts, slips out of its skin, and how in your life at that age you really want to reinvent yourself. I’ve talked to my wife about this; she moved around a lot, too, and you’d go to a new school and it was like you’d get a new chance to be a different person. Re-creating yourself: “I’m not going to wear these dopey clothes anymore. I’m gonna be…” —whatever.

So I liked being able to play with that kind of imagery and think about how the disease manifests itself differently in different people. And the idea too that in some cases you can hide it; you can button your shirt up and pass for normal—and avoid being outed.

BLVR: Before you were saying that you were interested in the normal surface and then what’s going on beneath the surface as a kind of boiling, raging, or disfiguring thing. But it’s kind of flipped in Black Hole, too, because what seems distorted is on the surface, but then a lot of those sick kids are really normal. And that’s part of the real sadness of the book.

CB: Yeah, exactly. You have sick kids that just want to go home and eat dinner and watch stupid television shows—live normal, mundane lives, but they’re forced into something else.

You can imagine being a teenage kid in a horrible situation and you run away from home, and you’re living in some place, some little tent in the woods, say, and you’re scavenging enough money to survive. You can imagine that that kind of thing is possible in the real world. But on the other hand, in Black Hole, that is forced on some of the characters. One of the characters is sitting at school, saying, “If my parents find out I’m sick, I’ll have to run away.” So it’s clear early on that she knows what the result would be. It’s the same as some kid saying, “If my parents knew I was gay, they would kick me out” or something. “There’s no way I can tell them.”

BLVR: There are no parents in the book who accept the sickness.

CB: When I started working on the story, I had this whole plot worked out where the kids are the good guys, and the parents and teachers are the bad guys. I’m over simplifying it, but I quickly realized I wasn’t interested in telling that kind of story— I didn’t want to turn it into a morality play.

And I realized that what I really wanted to do was just talk about the actual characters and their lives and not include many adults. Occasionally they’re there in the background; occasionally they might present an obstacle. But at that age in my life, my parents didn’t really exist either. My real concern was my internal life and my friends and what was going on there. And that’s what I wanted to focus on, and not muddy the waters by dealing with the characters’ relationship with their parents. I mean, it makes it very unrealistic in that sense, but on the other hand I wasn’t actually interested in the parents.

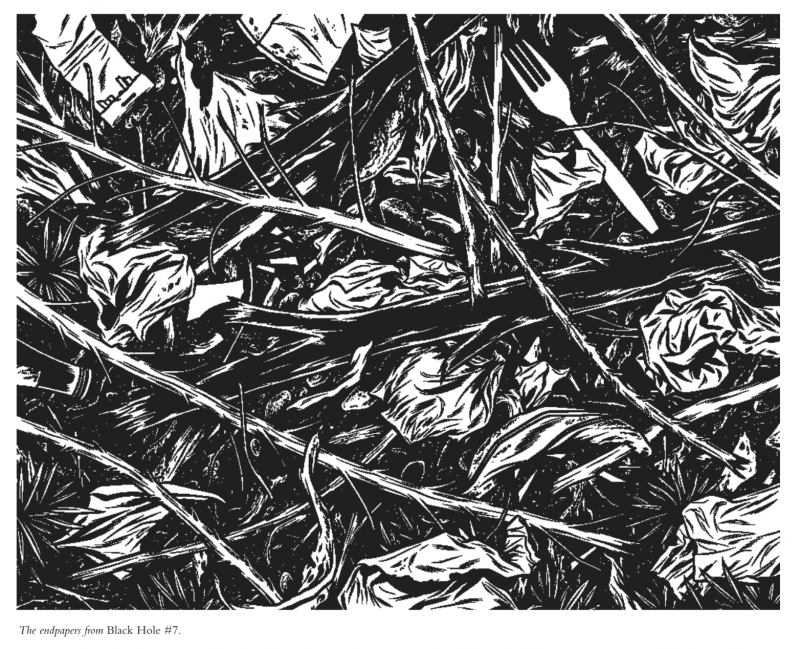

BLVR: One of the striking things about Black Hole is its visual precision. To give just one example, there are the endpaper images that show all the debris and detritus on the ground. Can you explain your process and how long it took, laying down all the ink?

CB: First of all, I’m a slow, meticulous artist, and the whole process of physically making all of those marks and drawing all of those lines takes a while. Add that to the fact that I’m not creating the most popular, mainstream comic imaginable. As a result, I’ve always had to do illustration and advertising work as a kind of straight job in order to make ends meet. I would work for a month on illustrations and then have a month to work on my comic. I would have to buy myself some time. Ultimately, I think it was actually helpful to have all of that starting and stopping, to be able to get a little distance and then come back to it with fresh eyes.

As for the endpapers, in some cases it would take a week just to do one of those—I was literally drawing every little grain of sand and every pebble and twig.

BLVR: Is working at that level of detail frustrating, or is it something that you’re totally comfortable with?

CB: It can be frustrating because of the time involved, but I’m comfortable doing it. Sometimes you’re approaching the drawing in more abstract terms; you’re thinking about shapes. You’re just squinting down on the design and thinking about what you need: dark shape here, another dark shape over here—that sort of thing. So all of that has to be designed and worked out. And then sometimes I’d have to go take a walk in our neighborhood to look at the trash and debris on the ground: “OK, a plastic fork would look good in there.”

BLVR: Can you describe your visual style? The way your pages look?

CB: There was a certain line quality that I was always really attracted to—this very thick-to-thin line that is a result of using a brush. There was just some kind of solidity to it, or a kind of richness…. I don’t know, just a feeling to it that I really liked.

So I started out trying to emulate the look of that kind of line, and took it to an extreme, I guess. Because if you compare the work that I do with the work that inspired it—more traditional comic-book stuff—mine looks much tighter and much more precise in a certain way. Not more mechanical, but more extreme. It’s also something that I arrived at slowly. In my earlier work I relied on shade patterns and cross-hatching to create a gray middle ground, but I gradually stripped it down to pure black and white.

I try to achieve something that’s almost like a visceral effect. The quality of the lines and the density of the black take on a character of their own—it’s something that has an effect on your subconscious. Those lines make you feel a certain way. That kind of surface makes you feel a certain way. That’s the best way I can describe it. If you’re looking at the texture of the woods in Black Hole, that starts to be a real element of the story, part of the character of the story. Or when Keith is in the kitchen, and he’s looking into a cup that has cigarette butts floating in it… Hopefully I’ve drawn it in a way that you’ll feel his disgust, or it reflects a sense of his despair. I don’t have to write “I looked down into the cup and saw…” or “The room was all trashed and it made me feel crummy.”

I don’t need to tell the story that way—that’s what the artwork achieves if it’s successful. Hopefully it makes you have some kind of gut reaction.

VII. NITNIT

BLVR: What is your new book about?

CB: I’m trying to put together my “punk” story. In a way, it’s impossible to describe. It deals with William Burroughs.

BLVR: As a character?

CB: No…

BLVR: As a theme?

CB: We’ll see. Hergé, William Burroughs… I’m working in a way that I haven’t before in that I’m writing the story page by page, or two facing pages at a time. I don’t have a page count, I don’t have a publisher…. it looks like it’ll be a long story.

William Burroughs was this kind of figurehead, this writer that punks embraced. So recently I’ve been re-reading him and some ideas about cutups fit in perfectly with the story….

BLVR: You mean on a formal level, with the way your book incorporates different styles?

CB: Yes. On that level, and it’s also something that the protagonist is interested in. At some point in the story he’s experimenting with cutups of his own—cutting his own bad writing in with Burroughs’s.

BLVR: Was Burroughs someone whose work you liked?

CB: He’s someone whose work I read during a period in my life. And yeah, he was someone who was important to me at that stage. Some of his pieces are really, really strong, lucid pieces, and some are pretty rough to get through and pretty flat. But as an author who experimented with a lot of different formal aspects of writing, he’s interesting.

BLVR: Does this book have a title?

CB: Not yet. Tintin spelled backward is Nitnit. But I found out that there are two comic strips that have already used that as a title. I want at least to have a character called “Nitnit,” or maybe one of the punk bands is gonna be “Nitnit.”

BLVR: We’ve talked about Burroughs….Are there other writers whose work you have particularly cared about?

CB: I’m using Burroughs specifically for this story because he really fits into that world—the punk aesthetic. But I’ve never been influenced by a specific writer per se. I stole a couple little pieces from Hemingway, little fragments that I used in Black Hole.

BLVR: Really?

CB: Very, very obscure, but it’s in there, taken from one of his short stories. I think about Hemingway—or his stand-in—getting off the train and seeing the little black grasshoppers; they’re jumping around and they’re black because they had been eating the burnt foliage. And then he goes off to the hills to fish, and the grasshoppers are clean and healthy up there.

BLVR: Which story is it?

CB: “Big Two-Hearted River.” The story’s about some kid coming back from the war and trying to go back to what was his former life—trying to recapture something that was strong and good, but he’s obviously— through the story, it’s not explicitly told, but you can see that he’s damaged internally, he’s damaged, and you’re seeing that through this very simple storytelling of him fishing. So in a certain way, that’s what’s going on in my new comic as well. You’re seeing this kid who’s in bed taking serious painkillers, starting to tell this story. And you’re going to find out how he got into that position, this kid who’s damaged, and looking back.

BLVR: Never quite able to recapture…

CB: Examining what he’s been through, and trying to come to grips with what he’s turned into. If you think about it, the ending of Black Hole where you’ve got Chris who’s going back out to the ocean again uses the same sort of idea—except I’m giving myself away again.

BLVR: No, continue, I’m deeply curious!

CB: OK, I mean, I’m just giving myself away! It’s basically taking the Hemingway story that I just described, of a character returning to this place from his past, and she’s doing the same thing, she’s returning to the ocean. The ocean has always been this great, cathartic place for her, and she talks about it in those terms. She says: “Every time I came out here, I had this place I’d go, I’d run up the beach to this special place—my favorite place on earth but this time I can’t run.” She’s coming back and it’s clear that she’s changed, but she’s struggling to come to terms with that.

BLVR: I thought the very ending of Black Hole was… “optimistic” sounds way too bulky. To say it ends on a high note is just too basic too. But it’s not a totally grim ending at all.

CB: No, I don’t think so. I’ve had people say, “Oh, she killed herself in the end, right?” Well, I’m not going to tell you how to interpret it, but that’s not how I wrote it. Because there’s a sentence right near the end: “I’ve thought about being done with everything, but how could I?” I included that for that specific reason: she’s not going out into the ocean to drown herself. There are other scenes earlier on where she’s going swimming, and diving under, and thinking, I just wanna be done with everything. So the possibility is certainly there. She’s turning those things over in her head, but I made it very clear that ultimately she doesn’t want to kill herself. On the other hand, there’s still the question of how is she gonna survive out there, how she’s going to continue on….

BLVR: The book doesn’t tell you. There’s not an implied ending in that sense.

CB: Yes, exactly.

BLVR: Her attitude at that moment is surprisingly good, given the shitty situation that she’s in of having the bug and being all alone.

CB: There’s a situation where she’s been invited to join this family for a meal, and she’s really, really hungry, and she really, really wants to, but then she has this brief glimpse—a memory of the horrible situation she’s just escaped from, and she just knows that she’s not able to join everybody yet. But she still has enough inner strength to go out into the water—to be able to begin healing herself.

BLVR: And she finally buries a picture of her boyfriend, Rob. I saw that as a good thing.

CB: I mean, it is very romantic and youthful, but that’s what you do at that age—you bury things, you burn things. And you ritually destroy something because you’re at a turning point in your life.

BLVR: I missed the Hemingway references in Black Hole even though I love Hemingway, so I feel like I need to go back….

CB: It’s probably good. I mean, I love the precision of Hemingway’s writing, but he also has this overly romantic edge sometimes that’s really revealing. It’s a balancing act that sometimes he’s very good at, very successful at, and sometimes he doesn’t manage. But yeah, that short story’s a good one. That’s where he succeeds. You think about all those little black grasshoppers. That’s a great, great image to think about.