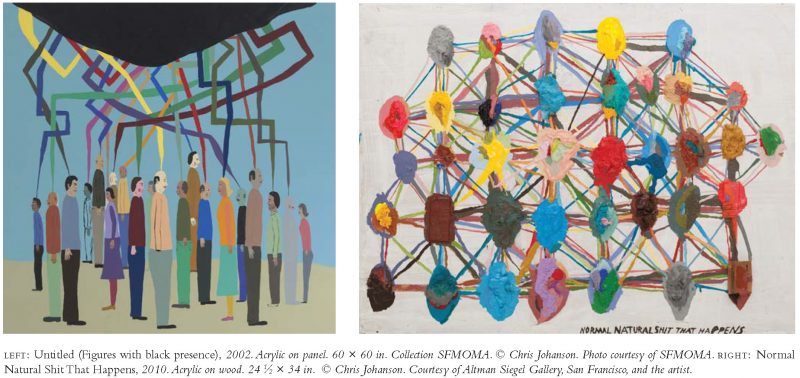

Artist Chris Johanson and I had lunch at Tropisueño on Yerba Buena Lane in San Francisco during the installation of his summer show This, This, This, That (June 3–July 30, 2011) at Altman Siegel Gallery. Over burritos, we discussed the velocity of Johanson’s art career. From drawing figures on random public surfaces in San Francisco’s Mission district in the early ’90s to achieving international fame after participating in the 2002 Whitney Biennial, Johanson’s rapid ascension in the art world forced him into the spotlight and precipitated a dramatic two-year hiatus away from it all.

—Natasha Boas

I. THE ART OF NOT-MAKING

THE BELIEVER: So you’re living in LA now, not Portland?

CHRIS JOHANSON: Yeah, we’ve got a view of the HOLLYWOOD sign and the Griffith Observatory. And then downstairs is my studio that I share with a bunch of black widows.

BLVR: [Laughs]

CJ: It’s a little two-car-garage studio. I have a pretty big studio up in Portland, and I just didn’t want to multiply that, you know? I just wanted to have a very discreet, kind of humble…

BLVR: A different type of work environment? A sunny climate?

CJ: Like, yeah, and we built all our furniture in our house, and Johanna Jackson, my wife, made all the textiles and then sewed everything together, and I Dumpster-dived all the wood and made all the tables and stuff.

BLVR: Everything is handmade?

CJ: Yeah, because we decided that we wanted to actually live… I think making art got too much like a job or something. So I took a two-year break and I just canceled everything and couldn’t do any more shows. I did a couple, but I didn’t go to anything.

BLVR: But you’re so back right now, and you’re doing all this new work.

CJ: Yeah, but I had to take a two-year break to be able to do it.

BLVR: That makes sense. You took a pause.

CJ: Yeah, because you know schedules—I can’t make art on a schedule like that.

BLVR: And was the intense scheduling because of the high demand for the work?

CJ: It was the high demand that I put on myself… pressures. I don’t care about that, especially not now. I’m over everything, kind of. You know, we’re just into living. It’s still how we make our money, whatever, but we’re trying to not have it be like it was. It’s not a very interesting life, really… Because to just make, when you have to live to make, is a very special place to be. I just thought, I have to make my art myself. I mean, I understood someone like Jeff Koons seemed to be doing a conceptual thing where he had everything fabricated by other people, and I understand that on some level if you don’t know how to—

BLVR: Make things yourself? The art of not-making?

CJ: Yeah, if you don’t know how to do things, then you get help. But when I do that it’s a real collaboration, or I give credit to the person who actually made it. I work with people who are on the same page as I am, anyway. It started as a very existential question, like: what am I doing? And getting on a plane seemed like the most ridiculous thing to do anymore. Traveling to another art-gallery opening or art fair just seemed wrong.

BLVR: So the new trappings of the art world interrupted your making, or your ability to live?

CJ: It—the art world—really did, and I don’t think I wanted this to be the way it was; I got sick from it, you know. I mean, living is psychological, you know, and there are things to process all the time. In the life of a professional… the creative life, there are all these challenges. The first challenge was, I’m making this; is this something I want to share with people? I’m having my first show; do I like what I’ve put up? Are other people going to like it? Then new factors entered. Now there’s money involved; am I selling art? How much is it selling for? It’s been a long journey already from skateboarding to shows with my paintings stacked on them to unpacking my own shows—I mean, making my art and packing it up and building my own crates. Then it was: Shouldn’t someone else be building my crates? These people that I work with take 50 percent. Like, I’m doing my part, what are they doing for their part? It all got to be too much. I mean, I am grateful on some levels, but I am into a new life now.

BLVR: So thinking of all these details that aren’t about the actual making, but about the commercial disseminating into the world, got to be too much.

CJ: Suddenly you’re a businessperson.

BLVR: So you were hating the business part, but you have to have a way of getting the work out into the world. You like that part of it—the sharing of it?

CJ: Oh yeah, somehow we got segued into that. I mean, it’s just like a preordered thing. I was a housepainter forever in this town [San Francisco], and that’s the job I really liked, because you just go to work and you get to work with people. I liked the people I worked with.

BLVR: Collaboration. Connection.

CJ: Yeah, well, I liked that the electrician would be from China and the foreman would be from Ireland and one of the carpenters would be from the South and some of the other painters would be from Mexico and there would be somebody from England, you know? There would be all these people from Eastern Europe, and we’d have these incredible philosophical discussions all day. It was a great job. But what I didn’t like, I didn’t like being a foreman.

BLVR: You didn’t like overseeing the team or being the boss?

CJ: Yeah, when it dawned on me that I had suddenly become all those things in my own private life while I was just trying to do my art, I realized, I’m not cut out for this. I’m not into this. It’s not my thing. So I just, like, stopped and started selling bread up in Portland.

BLVR: So did you make the bread?

CJ: No.

BLVR: You were just selling it?

CJ: Yeah, if I made it I would’ve had to get involved.

BLVR: You would’ve been the foreman again, the boss again?

CJ: I didn’t want to deal with that business part.

BLVR: So you were selling someone else’s bread.

CJ: Yeah.

BLVR: And then you got to interact with people.

CJ: It was beautiful. I’m doing it again this summer.

BLVR: That’s so great.

CJ: Yeah.

BLVR: So you were selling bread during your pause and you weren’t making work? Or you were making work and weren’t putting it out there?

CJ: Kind of both. I guess I really tripped out and I really couldn’t do anything.

II. VERTIGO

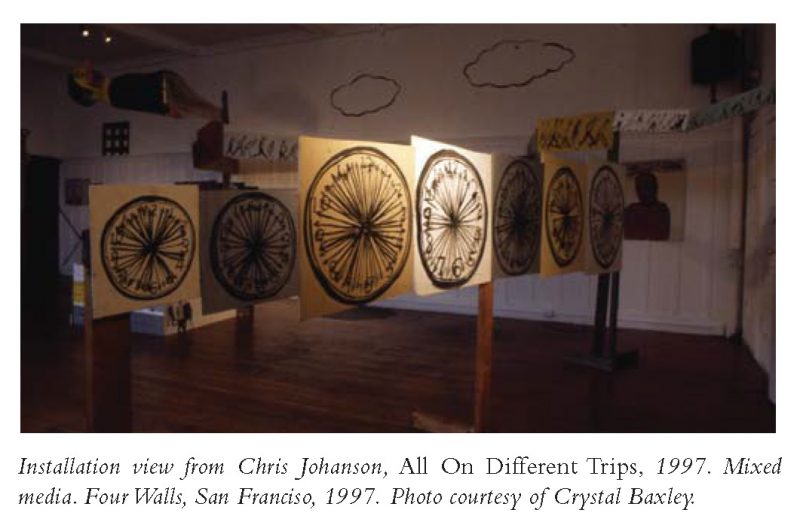

CJ: So I’m doing an installation right now that’s a body of work that I feel is pretty connected to all my stuff. It’s, like, one long narrative, and I always consider all my work I’ve been doing for the last… at least fifteen years, probably longer, like 1993, 1992 maybe, it’s, like, kind of the same piece, really.

BLVR: Nice concept.

CJ: It’s like it’s grown in bits and pieces. It’s changed. It’s interesting to me that it’s so autobiographical now. It’s pretty tripped-out for me. I mean, I’m making an installation for the Basel art fair this summer… The curator Jens Hoffmann asked my band to come and play, and he asked if I would also do an installation and perform. And so we’re building a stage and then we’re going to play.

BLVR: What’s the name of your band?

CJ: It’s called Sun Foot.

BLVR: Well, there’s the sun.

CJ: And we’re like an equilateral triangle rhythm circle. It’s a very equal thing. We all sing, we switch instruments, we’re all like a—

BLVR: So no one’s the foreman, no one is the lead?

CJ: Yeah, I never liked that. I mean, I like to hang my own shows most times, and most of the time when I do my shows it’s an installation anyway. But I have to tell you about an experience I had with a European gallery once with my early ’90s drawings… I had selected what work they could take from my studio, and we looked at it together and we made a grouping, but I told them I didn’t want anything to do with the install. I said it was their thing.

BLVR: And?

CJ: I went there and they had hung it thematically, not chronologically. And it was 102 drawings, and it was really emotional for me to go back in time to the early ’90s.

BLVR: The ’90s, early ’90s in the Mission—what they call the “Mission School” era?

CJ: Yeah—you live quite a few lives in your lifetime. I was living then—I’ve lived quite a few lifetimes, styles, and, you know, it was pretty emotional to see the work from that intense period of time.

BLVR: Something was really happening in the art world in the early ’90s to the mid-’90s in San Francisco.

CJ: The early ’90s for me was about being a sponge, absorbing this town. I think people say places always change, and they do, but I think people change more than towns change, actually. But this town has certainly changed over the years.

BLVR: So much!

CJ: But, you know, I think everybody that says that, they should rent the movie Vertigo—

BLVR: And realize it hasn’t changed at all!

CJ: Well, no. I mean, yeah, in some ways it hasn’t, right? But at the start of the movie there’s a scene where it’s, is it Jimmy Stewart?

BLVR: Yes, Jimmy Stewart.

CJ: So in that scene, Jimmy Stewart’s friend has a shipping company and they’re out at the bay. [Mimics voice] “I don’t know. You know, I’ve been here a while, and, you know, this town has really changed.” And I just started laughing.

BLVR: [Laughs] Of course!

CJ: Like, seven by seven miles, there’s nowhere to go. You can only tear things down for new things.

BLVR: This town has really changed.

CJ: Well, of course…

BLVR: Yerba Buena Lane wasn’t here five years ago to connect Market to Mission.

CJ: China Basin. It’s no longer full of trashed Winnebagos.

BLVR: And now there’s the gentrified, artsified Dogpatch area.

CJ: Yeah, like Dogpatch, I remember when all the bands could play there. And then the new yuppie neighbors said, No bands!

BLVR: Really? I’m sure they would want them back now.

CJ: No bands! This neighborhood is for me to do my meditation exercises after I get off work at my biotech or high-tech job. And this is for me only. This is my quiet time and space. You can’t do music anymore.

BLVR: I grew up in the ’70s in San Francisco. I’m a native. I remember seeing a bumper sticker in the ’90s during the dot-com that said NATIVE SAN FRANCISCANS, what the fuck happened? Which I thought was one of the best bumper stickers ever. [Laughter]

III. “HIPPIE PEACE PUNK”

CJ: I grew up in San Jose. I usually could get into all the punk shows using my pens to fake the stamp, and then when I got to be, like, sixteen, I started to know people—I did my first punk flyers when I was, like, sixteen for Ribsy, the Dead Kennedys, and the Dicks. Everyone thought the old Dicks were good when they moved here. To me, I liked the new Dicks, too. I mean, dude, that was the best peace punk to its fullest. Hippie peace punk.

BLVR: That’s true. What venue did you make your first poster for?

CJ: That was at the new Varsity Theatre in Palo Alto. It was for the Dead Kennedys. It’s a really embarrassing poster.

BLVR: Why is it so embarrassing?

CJ: Oh, because it’s so literal, it’s, like, a picture of Bobby Kennedy dead.

BLVR: [Cackles]

CJ: [Laughs] Well, I didn’t know what I was doing. [Laughs very hard] I showed my mom and she jumped. She was like, You don’t know what you’re doing!

BLVR: You can’t show that, right?

CJ: She was like, You don’t know, when he died, you know what I did? I cried.

BLVR: She had lived the historic pathos of it.

CJ: But I was not even thinking things through when I was that age. I thought I was.

BLVR: Your poster was just literal. That’s funny.

CJ: And then I started doing more punk flyers for people, doing punk flyers for my friend’s band Ribsy.

BLVR: Punk posters and flyers… early Chris Johanson? Social practice?

CJ: It’s really funny now—yeah—but so, so true