In his studio, Chris Martin and his two assistants peruse a leaning stack of his finished, mural-sized paintings. The canvases are as tall as the ceiling and as wide as the walls—they sometimes reach thirty feet in height—and it takes all three people to lift and slide them around the room. When finished, he is surrounded by a room of head-tilting, periphery-filling images and lit by the skylight above.

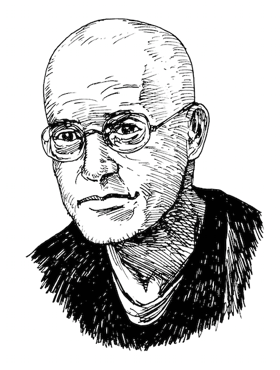

Martin laughs when he sees the older pieces that have been covered for years, some of which he can’t recall making. He leans against a pair of conga drums that he plays while giving lectures to art students. He teaches often and was an art therapist for many years, but his love of painting seems to be in spite of his distaste for contemporary art institutions. His work reflects this stance: it is unconcerned with trends or stylistic consistency or dictums about art, and its most glaring influences seem to come from artists outside of the art world—so-called vernacular artists.

Martin paints what he wants to paint, without post-modern complications. His art is direct. He sometimes pays homage to important figures in his life—Harry Smith, Paul Thek, Alfred Jensen, Bill Jensen, James Brown—by slathering their names on the image. He paints on records, slices of white bread, pillows, aluminum foil, and uses copious amounts of glitter—materials that seem immune to hifalutin artspeak. His canvases might be made from a thousand paint strokes or a single, bold symbol executed in just a few easy gestures. Either one of these approaches might take twenty years to complete, and he’ll note this on the canvas (e.g., “1992 –2012”). They can be enormous or handheld or glossy or muddy or bright, but what seems to be essential is that they are arrived at through discovery.

After looking at the paintings, a stack of art books by Dieter Roth, and a book of Martin’s photography, he says that we shouldn’t do the interview, since he’s a little sick and he’ll probably ruin the paintings by talking about them. So we talk about other subjects for a minute and then decide to do the interview anyway.

—Ross Simonini

I. “ANY ICE CREAM I WANT”

THE BELIEVER: The term spirituality is mentioned a lot around your paintings and I’m curious whether you agree with that connection.

CHRIS MARTIN: I think the word spirit comes from the Latin word for “breath”—spiritu—and I think the origin of the word spirituality has to do with breath and life force, the mysteries of the ancients and all this. The word is very suspect in much of the art world—the Western art world, now. Certainly, spirituality has become divorced from religious.

BLVR: Some people talk about how the art world is comparable to religion. It has a community, a shared language about something ineffable, a sort of icon worship.

CM: When people have a hard time with the word spirituality they’re assuming spirituality is something extra-mystical on top of what we all know to be true. But that’s just a big pile of steaming shit, because really what’s at stake here is a question of what’s real, and when one tries to engage with serious questions about what is real, then things can get very mysterious and spooky. I hate the word spirituality but I… um, sure, why not use that word? We can think about the breath rather than think about some kind of empirical, material, formal idea of what this society thinks is real. And the word mystical is an even worse word than spirituality—that artists take drugs, and then they add some crazy extra thing to what we all know is real. But our job as artists or as human beings is to investigate what we really think is real, and to come back to the tribe and say, this is what the world feels like to me. Joseph Beuys is a great example of that.

BLVR: So how does your work get to this idea of what’s real?

CM: That’s a really good question. As an artist, one doesn’t know what is real. And so there’s a search and a process of trying to locate something that feels or appears or somehow resonates with us on a deeper level. This is why art is such an interesting business to be in. In this last group of big paintings we were looking at, I was ripping pages of photographs from an astrophysics book and sticking them on the painting. And these physicists are guys walking around with suits and ties and heavy glasses. We don’t think of them as crazy artists, but if you follow anything about what physics says is real, what the scientists say is real—

BLVR: It’s crazy-sounding.

CM: Especially these days. But these are the scientists! These are the tenured professors at MIT. They’re not on drugs. They’ve got giant computer programs and they’re using tremendous logistical skill and rational analysis applied to this data of splitting atoms and zooming particles. Even high-school physics tells us that life is made out of electrical, whirling energy. So that’s some mystical stuff right there! Come on! [Laughs]

Earlier, I was haranguing you about how the Museum of Modern Art used to present Joseph Beuys. No one wants to talk about the fact that Joseph Beuys is a deeply Christian, mystical thinker. They talk about him as an important artist because he engaged in a new formal expansion of sculpture, blah, blah, blah. I can’t stand how most of the main institutions of modern art in America are completely embarrassed by or ignore this aspect of Mondrian or Beuys. And they act like it’s all about cubism turning into abstract painting and that’s what’s important. That’s so boring. What’s important is that, in Mondrian’s case, he was obsessed with finding this balancing of energy as a daily spiritual practice.

BLVR: In his painting.

CM: In his paintings!

BLVR: Kandinsky seemed like he had a similar approach.

CM: Yes, exactly. So Kandinsky was studying anthropological things about shamanism in Vologda and he comes back and a lot of those early paintings with the imagery of riders jumping over people—that’s all about shamanic dream travel. So Kandinsky comes straight out of all that, but all they talk about in the Museum of Modern Art is that his work is the invention of abstraction.

BLVR: Why do you think institutions frame art in such a formal way?

CM: Well, they avoid talking about life or meaning or content, which is a very hard thing to talk about. And they foreground a formal narrative of the development of art. All that stuff about flatness—it’s this idea that painting is a specialized discipline and that modernist painting increasingly refers to painting and is refining the laws of painting. But who cares about painting? What we care about is that the planet is heating up, species are disappearing, there’s war, and there are beautiful girls here in Brooklyn on the avenue and there’s food and flowers, and I love my dog and it’s life. That’s what we care about. I’m falling in love! This is the most beautiful boy I’ve ever seen! I love pine trees! This is what we care about. That’s why any kind of art is interesting—if it brings us as human beings in closer contact with life, and with the deeper mysteries of life. Who cares about whether it’s painting about painting and the flatness or if it’s in F sharp?! These are the mechanics of art forms. The institutions emphasize language. I personally don’t care about language, except when it helps me and us together to look at something that’s meaningful and gives us some kind of trembling.

BLVR: When you say you don’t care about language—I mean, you have all these art books here, each one with an essay about the art.

CM: I never read the essays. I just look at the pictures. [Laughs] I read about it and I think it just makes me angry. And then here we are talking about painting. Painters should shut up and paint and when we stop painting we should dance or have sex or get a massage or take a shower and we shouldn’t be talking about painting. But here we are talking about painting endlessly, and of course the part about painting that we all love is the part that nobody gets to by talking about it. So, yeah, I got all these books about art and I love art and I love the history of art and I’m always interested in looking at paintings. Any kind of paintings are interesting to me. You show me a painting in a barbershop, a painting by some kid, any painting. I love paintings.

BLVR: You’re interested in painting as opposed to just art in general?

CM: Yeah, that is just a personal thing. I was interested in painting as a kid and I always loved painting. And it’s actually kind of an embarrassing situation. If I was a young artist like yourself—you’ve got great cameras and video cameras and iPhones and there’s so much visual technology now and painting is an ancient, ancient thing. It’s not like painting’s so important—it’s just that it’s the thing that I personally love to do. One gets stuck with one’s own little interests at a certain point, and I love painting.

BLVR: You get stuck with them?

CM: Yeah. You do.

BLVR: You couldn’t try to become a filmmaker right now?

CM: Well, I think about it. But I don’t have time to make the paintings I want to make, so I don’t know how the hell I’m gonna have time to make the films that I also want to make. I mean, I do work with photography and mess around with other things and I’ve made sculpture and I used to do performances and I can sing really, really badly… but, you know, the issue here is also one of freedom. There’s this idea that artists are free and that means that we can do whatever we want to do. And it’s very important to engage with this idea, just as human beings, that we are free to do what we wanna do. So the real question becomes, then, what do we wanna do? And as one gets to know oneself, one finds that there are things that return again and again that you wanna do. And it’s not always some sense of great joy, it’s some obsessional thing where I can’t stop doing this. And as an artist, particularly as a young artist, one also encounters the things that one can’t do very well. I remember as a kid there was a guy named Brad Ferris who would draw cartoons and it was just magic. He could draw faces and people and we used to just go out at recess and watch this kid draw. And I could never do that. I can’t draw a face to save my life. I wanted to be a rock-and-roll musician but I never was a good musician. I really wanted to be a pro football player but I’m like a skinny little guy that never had a chance, so one finds that one is also free to do anything, and then one finds, well, actually, this is what I’m able to do and this is what I really find myself compelled to do.

I mean, in America this idea of freedom means I can have any ice cream I want, I get in my SUV and drive right over to your house and reach in and grab your wife. I can do anything I want! I’m in America! But that isn’t actually about freedom. That’s about power. The point of an artist is to find out what are the flavors that I must work with. Finding one’s freedom is about surrendering to your helplessness. I’m a painter. That’s what I do. And sometimes I’m very happy about that and sometimes it’s just what I gotta deal with.

II. THE BAD ONES

BLVR: You make a lot of paintings. I heard you once say you start eighty paintings in a season.

CM: Generally, yes, I am someone that works a lot and does a lot of things. And I used to paint paintings and then repaint them and repaint them and repaint them. And so there were a lot of different paintings underneath each painting and I used to think when I first got to New York that that was a badge of honor, that we were supposed to be drunken abstract expressionists who reworked and reworked and were never satisfied. So I did that for a long time. And then at a certain point I began to give myself permission to—instead of painting over these paintings, I was just gonna paint all the paintings. And I think I started giving up on the idea of making good Chris Martins and I just said, I’m gonna make all the ones that I think of making. And I found it was difficult, at first, to not destroy things that were so embarrassing or odd. And the discipline there was to make all these paintings and just leave them for a while, and start lots and lots of paintings. So I start a lot of work and I don’t necessarily finish a lot of work. And I think there was a point where people said, Oh, Chris Martin’s an abstract painter, but I’d always been making these odd, figurative things as well. Many of which were destroyed, but many of which were just not shown. So then I began to give myself permission to—if I wanted to paint a duck, I could paint a duck, or a tree. I could do that. And then to leave the paintings around and try to figure out what they were about. I remember once talking to Richard Tuttle when he was choosing a group of work for a show—he was vehement with me, saying, I’m not gonna choose the good ones, I’m gonna try to give them a representative group of what I’ve been doing.

BLVR: From good to bad.

CM: From good to bad. I’m just gonna show that, like a scientist, this is the result that I got these last few months. And I remember him saying that it’s important that you don’t just try to show the good ones. Show them what happened.

BLVR: Do you do that?

CM: I’ve been trying to do that, yes. Then you deal with actual dealers and gallery owners and they’re often not so interested. [Laughs] They have these ideas about quality… [Coughs] Next question! [Laughs]

BLVR: What’s your definition of “bad” or “unsuccessful”?

CM: Well, that’s a wonderful question, because as an artist it’s very interesting sometimes to say, I’ll try to make a bad one. And often the kind of energy around the bad one is actually great. And the real assumption behind this is the idea that artists know what they’re doing. Or that we have great taste. We have great, discerning judgment about what’s a good one and what’s a bad one. And this whole, horrible juggernaut of graduate schools and art schools in America is predicated on the idea that everyone gets together and they put up the work and they try to develop critical thinking. “This wasn’t so good because the purple doesn’t pop, and this linear quality is better,” and so young artists are trained to make it better and better. But I think that doesn’t lead to better paintings. The idea is that we know what’s a better one or what’s a worse one. And I’m not sure that we always know what the good ones are and what the bad ones are. I have photographs of paintings that I did in the ’80s and I destroyed them. And then I repainted them in the ’90s and I destroyed them. And a lot of times the ones that I painted in the ’80s were fine. I should have just left those.

But, again, the planet is flaming, we got serious problems. And so the question becomes: what are we doing about it as painters? We’re off here trying to make “good paintings”? Who cares what’s a good painting? How about a painting that’s disturbing, raw, or we don’t even know what it is? That’s probably more helpful to all of us than these very well-made abstract paintings.

All the children of America, up to age seven or eight or nine or ten—they’re really great artists. So here we’ve got this amazing work that very few people pay any attention to, and it’s not valued by the culture. In fact, one of the great dismissive lines by popular culture on painting is “My kid can do that.” And of course the truth is their kid could do that, but could they do that? Their kid’s a genius! They’re the ones stuck in some uptight vision of they can’t do it. And so one sees examples of paintings that we don’t understand, a wild energy or freedom. We see it all the time, looking at paintings that you find on the sidewalk, half-finished paintings, thrown-out paintings. You could buy paintings online made by elephants these days. And elephants are pretty good painters. So if an elephant can make a good painting, then who needs an MFA from Yale? I mean, maybe we should start accepting elephants into graduate school.

BLVR: Do you try to short-circuit your skill as a painter to get to a more childlike or animalistic kind of drawing?

CM: Well, there are lots of ways to do it. You can draw with your left hand. There’s a great bunch of de Kooning drawings that he made with his eyes closed. And they’re great drawings. And he used to make these drawings looking at television and not looking at the drawings. I knew a guy who used to set his alarm for two or three in the morning and he had this drawing paper and he’d wake up—but not be quite awake—and he’d start drawing. People would obviously try drugs or caffeine or not eating. Miró claimed that he wasn’t eating when he made the Constellations series and that’s why they were so good. That’s pretty hard-core.

BLVR: Have you tried anything?

CM: I tried it all. [Laughs] All of the above. I was watching a movie about Miles Davis last night and at one point one of his sidemen said Miles came up to him and said [speaking in a raspy voice], “You know why I don’t play ballads anymore, don’t ya?” And the guy says, “No, Miles, I don’t know why,” and he says, “᾽Cause I love to do it.” And there’s this sense that one has to challenge oneself as an artist, and not do the stuff that one is “good at” all the time in order to keep it fresh. There’s a great quote by de Kooning when someone asked him, “How do you feel when all these younger painters are painting just like you?” and he said, “Well, they can make the good de Koonings but only I can make the bad ones.”

III. THE SLIPPING GLIMPSES

BLVR: When you put pillows or bread into the painting, do you consider them to have a different inherent meaning than paint? Or is all just purely intuitive?

CM: What you said, does it have meaning or is it intuitive? That’s very interesting, the way you ask that question. You see, American society sets up this dichotomy.

BLVR: Well, I meant, do the materials have conscious meaning?

CM: Yeah, exactly. Like conscious meaning is the real meaning. I’m giving you a hard time here, Ross.

BLVR: You are.

CM: Is it real meaning or is it just intuitive?

BLVR: [Laughs]

CM: You know, there’s a great quote from Robert Creeley, the poet, where he was giving a reading out in Iowa somewhere and at one point someone’s holding up their hand and they ask, Was that a real poem or did you just make that up? And I love that story because there’s the sense that with real art the artist sets out to have some kind of meaning that they take out of books or that they’ve copied down beforehand or they have some kind of theory about tragedy or women’s rights or some kind of poststructuralist whatever, and then they put it into the painting

BLVR: Well, a lot people do that, right?

CM: Those poor fucks.

BLVR: [Laughs]

CM: If I paint a painting of a pillow and I’m thinking, This is about dreaming or it’s about my grandmother, and you look at this painting and it reminds you of freshman year when so-and-so did something—that meaning is in that painting, of course, that’s all there.

BLVR: That’s interpretation. I was talking about your own personal—

CM: No, but any interpretation is the meaning of it.

BLVR: OK, so if you are making the painting and within arm’s reach, equidistant, are both a pillow and a piece of bread—now, is there any reason for you to choose the pillow or the piece of bread? Or for you is that not really the point? Is there no reason to choose the bread or the photograph of the physicist or the pillow? Is it all just stuff? Do you have an intention?

CM: But if I answer this question, how do you know I’m not just making this up? Or pretending, Oh, yes, I had wonderful ideas and I put them in place and I realize I’m a genius. You reach for orange and you run out of orange and you use pink instead. Maybe you reached for orange because it was going to be a Halloween painting, but now it’s gonna be about… pink! The point I’m trying to make here is that of course I have all kinds of ideas in my head and then I’m always making mistakes. I’m always getting it wrong. I’m always conflating things. I thought I was going to do this and I ended up doing that. I thought I was going to paint a skull in it and that it would be a profound painting about death, but it turned out that the skull looked sort of stupid and goofy and it became a painting about Mr. Magoo. It’s important to realize that we try. It’s not like I’m advocating that we turn off our rational selves or we turn off our influences. We can’t do any of that. What’s been important for me is to open myself to the process and open myself to the resulting images so that I don’t know the meaning. When I put a group of photographs together in a painting I often tell myself it’s a story. And I tell myself a story. It starts here with this galaxy, then there’s a frog, here’s a mushroom, and here’s my mother, and if I’m successful, these objects have their own reality, and they have reality that is hopefully greater than something I could have planned.

When I came to New York in the mid-’70s, there was this tremendous energy around abstract painting and constantly trying to get rid of the extraneous meaning. There were all these people trying to make paintings by stripping the language down to some kind of platonic, perfect painting. If you made a painting and someone said that it looked like a landscape, that was bad, because now you were stepping back from the avant-garde achievement of what abstract painting could be. But I think the great masters are people like de Kooning, who consistently opened his formal vocabulary to include every kind of idea—it was a shoulder, or it was a breast, or a light on the grass, or it was water, and it was about looking at the sidewalk. It’s what he called slipping glimpses—where something gives you that kind of shiver, and you see that it is the light on the sidewalk and it’s the water rippling at Amsterdam and it’s the little song your mother used to sing you. It all could be in there. Pure, abstract painting doesn’t exist. And even if it did exist, who would want that? Not me.