Clare Rojas (b. 1976, Ohio, lives and works in San Francisco), who has produced work and exhibited internationally since the ’90s, is often placed within the context of what is considered the most definable art movement to emerge out of the Bay Area in the late twentieth century: the “San Francisco Mission School.” This core group of artists, including Barry McGee, Margaret Kilgallen, Alicia McCarthy, and Chris Johanson, was made known through exhibitions at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and the Luggage Store in San Francisco, Alleged Gallery in New York, the documentary Beautiful Losers, and, later, through notorious shows with Deitch Projects.

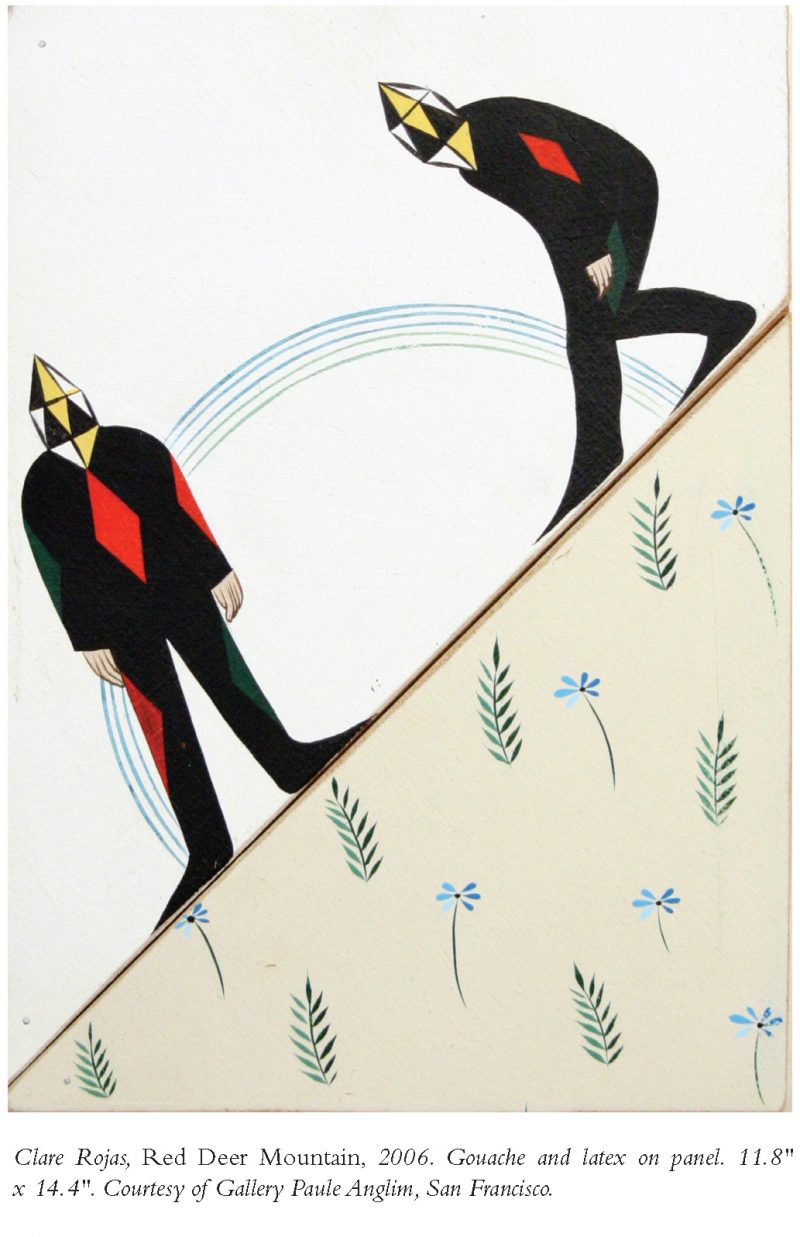

Rojas uses a wide range of media, including painting, installation, and video. Her images reference high art and popular culture—West Coast modernism and Quaker art, Byzantine mosaics, Native American textiles, sign painting, and outsider art. Rojas also sings and plays guitar and banjo under the name of Peggy Honeywell. She’s produced several CDs with her own songs, including Faint Humms (2005) and Green Mountain (2006).

Clare Rojas participated in this conversation at the Museum of Craft and Folk Art on Yerba Buena Lane in San Francisco a few months ago to discuss We They, We They—Rojas’s first solo museum show in San Francisco. The standing-room-only audience gathered to see Rojas’s work and hear what the artist had to say about domestic space and the myth of the Mission School.

—Natasha Boas

I. STORYTELLING

THE BELIEVER: Your three iconic prints—the hooded man, the dark haired-woman, and the red house. Let’s begin with those.

CLARE ROJAS: I was invited as the artist-in-residence to make prints a couple of years ago, and I think that really made me remember my roots as a printmaker, as an art student at Rhode Island School of Design, and how that informs how I paint.

BLVR: People often try to find a narrative within your work. They want to piece together a story with your images. This is part of your involvement in storytelling, and the folk-art tradition. We see it with your children’s books—you create stories. I wonder if there is a specific story you are telling with these three elements.

CR: That’s interesting, because at the time I made those three prints, I started writing my novel, and I think that the writing process is a very isolating process. You have to be alone and you have to be really alone—anyway, I do—and very quiet and focused on trying to write. And before my pen could hit the paper, I had to figure out my whole story. I had to start very simply, and I realized I didn’t know how to write, and I tried to take some classes, and my husband was very supportive at that time, because [laughs] I would run off and be like, “I’m writing!”

BLVR: “I’m not making any more prints! I’m writing!”

CR: “I’m not making any money! I’m writing!” And the thing is, again, it was the idea of explaining every little detail that I thought was overkill, but for the visual arts viewer it isn’t. And it reminds me of how to get down to the bare bones of…

BLVR: The minutiae.

CR: Wanting to be graceful and precise and detailed.

BLVR: You move easily from the highly detailed smaller pieces, the intimate pieces, to these very bold, what you call “blown-up” images, and you’re an artist who’s able to produce these two distinct bodies of work. You move from one to the other somewhat seamlessly. I’m wondering if you could talk about the installation process, the immersive floor-to-ceiling paint on wood paneling, as well as these very detailed, delicate pieces.

CR: I think that has a lot to do with the support of the museum, and the crew, to have access to the materials and the time and the help that go into making these big installations. It’s just not done alone. It’s about teamwork. I think I work so long and hard on the small pieces that by the time they’re done they are imprinted, somehow, in me.

II. DOMESTIC ABSTRACTION

BLVR: Do you see yourself taking a new direction in your work with this particular installation, with the emphasis away from representation and into abstraction? Can you explain what you’re calling “domestic abstraction”? It’s clearly an important shift, and it happened extremely quickly. I don’t know if it’s due to this particular gallery space, the context of a craft and folk art museum.…

CR: It didn’t happen quickly. I’ve been secretly making these abstract works for two years. I have works in this show from 2003 to the most recent from this year, and I’ve changed so much. I like spaces to feel intimate, so they have to kind of engulf you. It’s like trying to fit into your old jeans from high school. [Laughs] Kind of nostalgic, kind of depressing, kind of challenging, embarrassing, all those things. When you invited me and I came to see your space, I was just so excited, because it was perfect, with these weird walls.

BLVR: You can move the walls on tracks and arrange them as you like.

CR: Everything just kind of fell into place. I was really engaged on working with my focus on interior space. As I’ve said in the past, I truly believe that politics are in the house, in the home, on an individual basis, for everybody—especially for women, and that’s where the power is. In a nice, loving way, of course, but that’s where it’s at. So I think I went inside for that.

BLVR: We’re sitting by the fireplace tonight. [Gestures to the wall-painting panel behind them, a large architectural fireplace in an empty room] And yes, there is clearly a pivotal new moment in the work: you are working out this figurative/abstraction dance—pushing the two traditions further. There’s another piece that we’re showing that has not been shown yet, which is an interior piece, very much a detailed domestic scene without any people in it. We’ve known you for your naked men and laughing ladies. There isn’t one naked man in the room this time around. [Laughter] I’m very intrigued by that small domestic interior painting and the fact that the figures have ended up on the shelf as figurines. It seems to encapsulate your idea of domestic space.

CR: That’s where it all happens: on the inside. For me, interiors have become, in a sense, portraits. The inside becomes the figure that I am now representing. There are a couple moments in people’s lives that kind of click. I had that moment a long time ago, and it resonated with me—it still resonates with me. My mom had cancer. She was going through a brutal divorce. And it was the middle of winter in Ohio, in the Midwest. We lived in a ranch house, and the snow was falling. It was a constant battle to keep the ceiling from leaking onto our puke-green rug.… But anyway, you don’t have to feel bad for me. [Laughs] There was a moment where the roof fell in and the snow was kind of almost beautifully piling up in the middle of our family room, and I realized that that house was so connected to my mother and the way she was feeling. At least that’s how I interpreted it. And I never forgot that. I believe the space we live in fills us, and we are part of it.

III. NOT STREET

BLVR: It’s interesting that your work is identified, again and again, in all the curatorial statements, with street art, and graffiti art, and yet, in fact, it’s so obvious that it is not at all associated with those movements. It’s very meticulous and would fit in the continuum of those very methodical female domestic traditions such as quiltmaking, stitching, embroidery, tapestry, knitting….

CR: Street art is pretty dirty and it’s not legal. Who wants to be working out in the street? [Laughs.] This streetart thing… I really do appreciate street art, of course. Some of my favorite artists are associated with street art. [Laughs; her husband is the graffiti-friendly artist Barry McGee] So I can’t engage in that discussion just to set that record straight. If I could get away with working in the street, who knows where I would be. Anyway—I think inside really is the safest place. And I don’t mean that in an oppressive way at all. Solitude is a very powerful place. Quiet is powerful.

BLVR: We are inside your installation. There’s a moment in this room where all of the architectural planes and painted lines will line up. You discussed this as an “autobiographical point.”

CR: Self-portraiture of some kind might be happening. As I’ve matured, I’ve tried, in a way, to understand that I can only see the world the way I see it. And it’s very difficult to tell other people what to do or how to think or how to feel, so I thought about the whole perspective thing from where I see and what I see. From five foot three. When my husband and I go to music shows or whatever, he’ll look down at me and say, “What do you see? Just the backs of people’s heads?!”

BLVR: [Laughs]

CR: My height. Yes, there is a point in this installation where all the different planes line up with my perspective, and this is my self-portrait, I guess. I want people to see my point of view. My goal in life is to get a black belt in a martial art, and it’s just not working out with my schedule. But I took this class, and it was beautiful, in aikido, and it really had an impact on me. It’s not aggressive. You don’t attack the person. You just kind of lead them gently into your movement. You see their point of view and they see your point of view. At any moment you could kill them, but you’re not going to, because you’re just trying to have a conversation. [Laughs] You’re still very empowered. But I like that. I think that is genius—to share that kind of perspective!

IV. FEMINISM MEANS THE WORLD

BLVR: What do you say when people use the word feminism in relationship to your work? How do you respond to that? It’s so hard to talk about feminism in an artworld context, at this point in time. Do you think there is a response to your work as feminist? Or as strong female work? What does that mean to you?

CR: Um, it means the world. I don’t think it’s ever a bad word. It’s a civil-rights issue, and we’re still fighting for it. Statistically, things have not gotten better.

BLVR: [Gestures to Rojas’s art] We’re still doing the domestic scenario….

CR: I think people are really afraid to talk about it. This is a tricky thing, this whole domestic-feminist thing. Part of me identifies domesticity with a kind of Protestant, behind-closed-doors attitude, and what I guess I’m trying to say is that wherever that woman goes, whatever space she fills, that power, and that strength, and that wealth, and respect—she takes it with her. She embodies that space and owns it. For me it’s about owning that, wherever you go. Any space you go into is your space to own.

BLVR: One critic calls you “Grandma Moses meets Kara Walker”—in effect, outsider woman folk artist meets insider art-world contemporary.

CR: Women have been through a lot. And our history hasn’t been told. And it needs to be. Go to any museum, you won’t see a lot of art by women artists exhibited.

BLVR: By the way: how did you come up with the title We They, We They?

CR: It’s off an old game scorecard. I was cleaning—I am perpetually cleaning—and I found it, and I thought it was a perfect title.

BLVR: You reference quilt-making directly by calling your wall paintings “wall-quilts.” Why quilting?

CR: I grew up in Ohio with Amish quilters left and right. My mom quilted. As I got into quilting, and started researching it, I figured out that that was the platform that was the main ground for a lot of women to talk about politics. And they didn’t have any other platforms; they weren’t allowed to talk about politics other than in those circles. That’s where our history begins. These women are mathematicians, they’re engineers. To make some of these quilts, I look at it and I think they’d need tools…. There’s no way men could even come close to figuring some of this stuff out. Amazing. I have so much respect for it.

I’ll never forget dropping my mom off—her group was making these baskets for the men and women in Iraq, a lot of the women had sons there—my mom was one of them, my brother was there, and I borrowed her car and I picked her up, and every single bumper sticker in that parking lot was, like, a radical feminist bumper sticker. You know, like you don’t like abortions, don’t have one kinds of things. I felt like those women—those are the ones who talk for our rights, and this new generation, I don’t know. No offense to anyone…

And as far as men in the art world? Yeah, they dominate. I’m not going to shy away from saying it. It’s really annoying when the media and the galleries and museums make it known that men are more interested in seeing men, and women are more interested in seeing men. That seems to be the status quo, and it doesn’t matter if they’re objectifying women or placing them on a pedestal—these artists and images are celebrated and applauded, and that really makes it hard. But the women at MOCFA have opened the museum up, and I think it’s a radical move on their part, and for their gender, to open it up and create a space where they’ve given the artists this freedom to express themselves however they need to, and this space is like, it’s— you can attack it as an individual and create the base that you want.

V. WAS THERE EVER A MISSION SCHOOL?

BLVR: The do-it-yourself aesthetic is definitely part of this new generation, and I think that it’s not a backlash against the new post-digital world, it’s actually part of it; we are culturally immersed in both simultaneously. We are tweeting and communicating on our iPhones with our thumbs, and at the same time we are knitting and crocheting. We’re using the same hand-eye skills in tech and craft.

CR: And having respect for both. As we have said in our conversation, it’s about respecting both.

BLVR: You mentioned that the first time you experienced the San Francisco scene was actually when you were in Philadelphia in 2001, the East Meets West show. Could you talk a bit about that for a moment?

CR: East Meets West was curated by Alex Baker in Philadelphia, at the Institute of Contemporary Art there. I had graduated from RISD, and a group of us had migrated to Philadelphia. I had worked as a secretary, and after work I would paint. And Alex became a friend, and said, “Hey! I’m gonna put you in the show. There’s three of you from the East Coast and three of you from the West Coast. You know, so work by Margaret Kilgallen and Chris Johanson, and… umm… that third person…”

BLVR: What’s-his-name. [Laughter]

CR: Yeah, what’s-his-name. Barry. And I was so excited and inspired by what they were doing. And I guess there was this similar kind of movement happening on both coasts. We had started this space—Space 1026—none of the spaces in Philadelphia were showing the work that we were making. So we made our own space to show it. Everyone was a musician and everyone was an artist and everyone was a printmaker. It was definitely a community. We didn’t always get along, but it was definitely a community of artists.

BLVR: The art world tends to historicize this group of artists in San Francisco emerging in the ’90s, and refers to it as the Mission School. It’s heavily embedded in a sort of regional identity, and you have made us understand that this was a moment in time, that it wasn’t just a San Francisco movement. These same concerns in painting were happening on both coasts at the same time.

IV. AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION

WOMAN IN THE AUDIENCE: What about other contemporary female artists? Or male artists?

CR: I have to say that my female inspirations are from literature and music. We’ve talked a lot about Patti Smith.

BLVR: Yes, we’re big Patti Smith fans.

CR: I’m reading The Bell Jar right now. I’m trying to catch up on my female literature. I think Annie Dillard is one of my favorite writers. Those writers’ scenes are so poetic, and so visual.

ANOTHER WOMAN IN THE AUDIENCE: What’s your studio life like? You’re obviously very prolific, and I wonder what a day looks like for you.

CR: Oh, goodness, really? [Laughs]

WOMAN: How much time do you spend in the studio? Or what is the studio?

CR: When you have a child—I’m just gonna be honest here—your time is very limited, and you work very fast and efficiently. I work in very small scale in the studio, and I sort out all my issues with painting there. And then when I go to make things big, it has to be very fast. Usually I wake up and then I hit the ground running.

A THIRD WOMAN IN THE AUDIENCE: I know you just did a public art commission for the San Francisco Airport last year called Blue Deer and Red Fox. What was your experience with making public art?

CR: It took so long. It took, like, two years. And I had made the painting in a day. And I just kept thinking, Just let me paint. But it had to be printed and it had to be UV protected and they had all these restrictions. But that said, to have a piece at the SFO, it’s pretty moving. It’s pretty cool. If I ever fly to China, I hope I see—it’s in the international terminal, boarding area G. I worked with Magnolia Editions with that, and they printed at that massive scale. That was fun!

A FOURTH WOMAN IN THE AUDIENCE: I think in this gallery you have created a living room, and a place for dialogue, and you’ve really created community, and it’s very intimate, so thank you.

CR: It should be inclusive. I think in the past I was angry, and working through that anger, this is what has manifested from that inner pulling-back, and being checked. My inner feminist, too, and humanist, mainly humanist, coming down from that. And we’re all connected. All of us. And that community is so important to me. To be able to communicate to everyone, every child, every age, to me is now what I view as super important. So thank you.

FOURTH WOMAN: So what is your personal interior space like?

CR: Just a wall and a desk. Right now it’s really clean, ’cause I did that all day.

BLVR: Cleaned house?

CR: Yeah, cleaned house.