A recent Daniel Clowes cartoon in the New Yorker closed with this punch line: “I mean, think about it—we’re just these weird organisms on a rock in space!” The joke is part paranoia, part truth—the worldview that drives his oddball characters. Clowes is a trenchant observer, and he consistently turns that which is most familiar—the human life-form—into something otherworldly and frequently repellent.

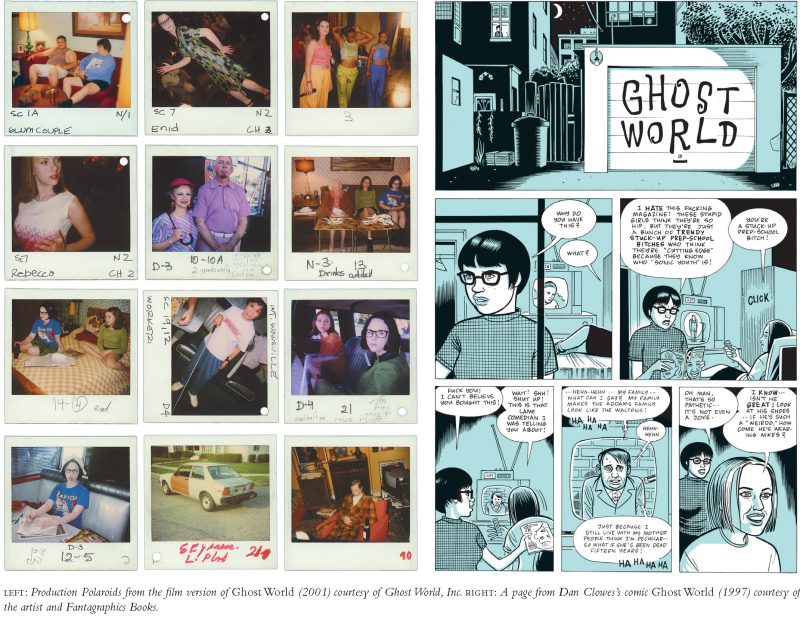

But as his more recent endeavors have shown, the cartoonist has, by his own account, softened a bit toward his characters. In 2007 and 2008, Clowes created Mister Wonderful, a weekly strip that ran in the New York Times Magazine. In deciding the fate of Marshall, its hapless hero, he confesses, “I couldn’t do anything bad to this poor guy.” In the special edition of Ghost World, published by Fantagraphics in 2008 to mark the tenth anniversary of the original hardcover edition, Clowes admits that in re-reading the book, he expected to feel an authorial distance from the heroines’ travails; instead, he experienced an affectionate sympathy. He also observes that Enid and Rebecca’s story has taken on a life of its own, and in so doing has caused the author to “question [his] own existence.”

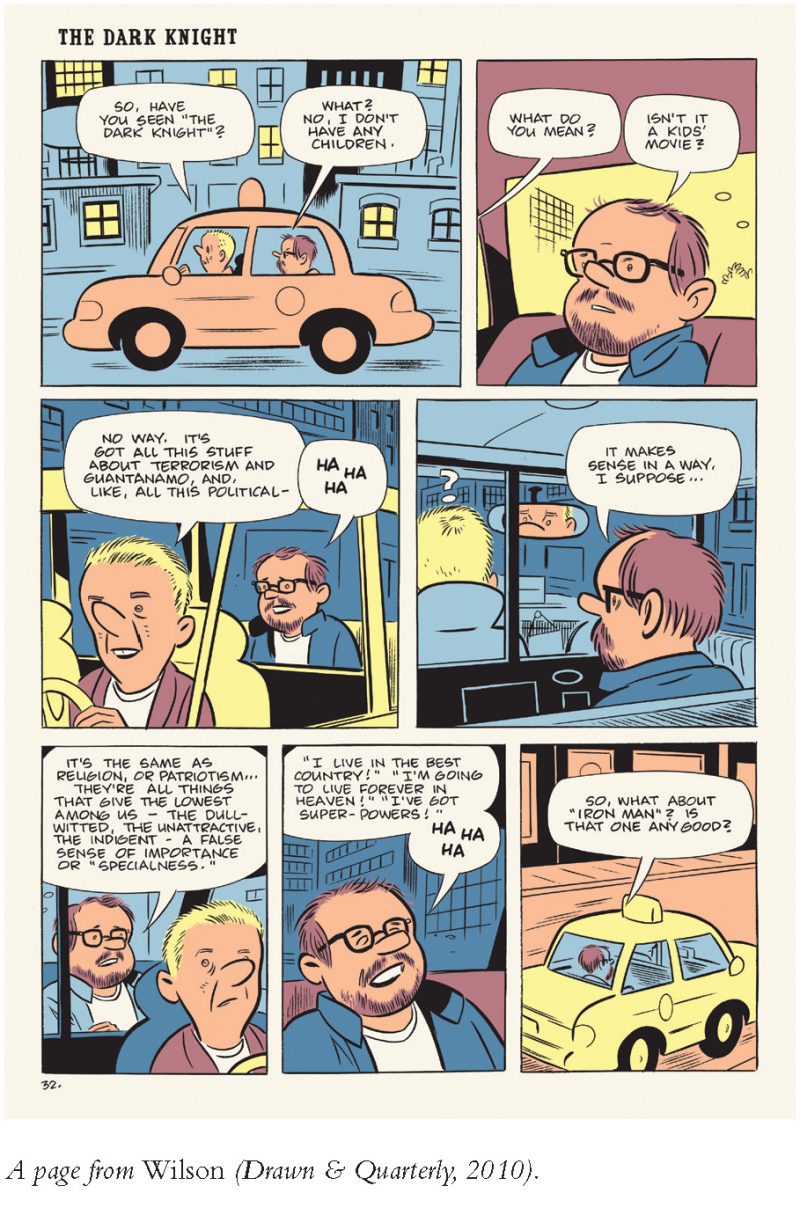

We first met up for a late breakfast in SoHo in August 2008, to reminisce about Ghost World. Part of the book’s popularity stems from the 2001 film, for which Clowes wrote the screenplay, and our conversation turned to his more recent film and television projects. When we spoke again, by phone, last February, talk of film and TV brought us back around to his exceptional new book, Wilson (published by Drawn & Quarterly), which stages the title character’s daily efforts and irritations as a series of Peanuts-like gag strips. Wilson, who fits seamlessly into the Clowes pantheon of socially challenged characters, seems to have taken his creator’s existential wanderings to heart, and Clowes, for his part, acknowledges feeling equal parts disdain and admiration for this middle-aged loner.

—Nicole Rudick

I. “DOES ANYONE WANT TO TALK ABOUT JOHN UPDIKE’S NOVELS FROM 1985?”

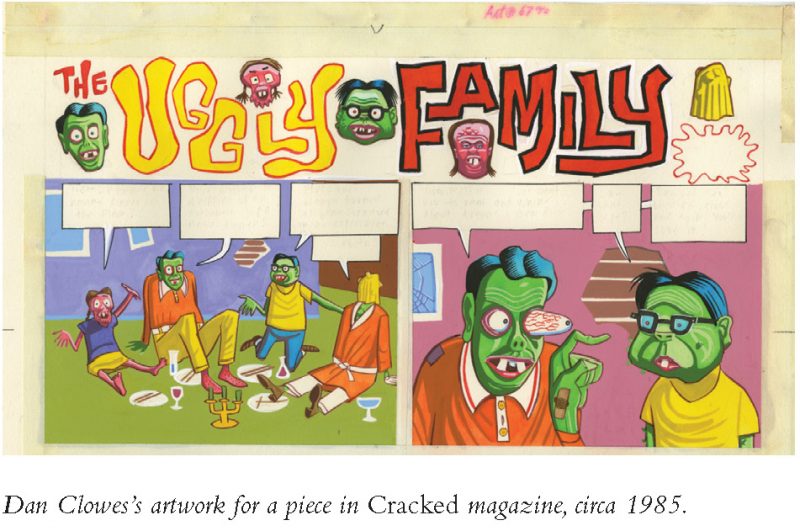

THE BELIEVER: Your first story, a Lloyd Llewellyn story, appeared in Love and Rockets in 1985. But before that, you wrote for Cracked, under the pseudonym Stosh Gillespie. Was that your first comics work?

DANIEL CLOWES: That was my very first work.

BLVR: How did you get involved with Cracked?

DC: I had a roommate in college who was an unbelievably persuasive guy, and one day he saw that they needed a gopher at Cracked for the editor in chief, and he went out and got this low-level job—I don’t even know how he got that job with no credentials at all—and within, I think, two months, he was the editor in chief of the magazine. Since he owed me like three months’ rent, he paid me back by getting me work at Cracked, which is more than I would ever have wanted at the time.

BLVR: Why did you write under a pseudonym?

DC: Because I turned in my first story under my own name, and the publisher, who knew nothing at all about comics or humor, no idea what was good or bad, had just bought the company and wanted to show that he was on top of things. So he took the pile of art for the subsequent issue, flipped through it, and said, “This is good, this is good, this is no good, this is good.” And mine was in the “no good” pile, so my friend the editor said, “He doesn’t know what he’s doing. Just white out your name and come up with a pseudonym and resubmit it.” Which I did, and the guy was like, “Yeah, this is great.” So I was stuck with that name.

BLVR: What were you reading at the time? Who influenced you?

DC: I was reading a lot of over-the-top pulpy stuff, like Mickey Spillane, which was the opposite of what was going on at the time in the culture. I always read everything from a certain era about ten or twenty years after it’s over, and I’m like, “Does anyone want to talk about John Updike’s novels from 1985?” In terms of comics, I was really interested in underground comics, which were still available. There were still head shops in the West Village where you could buy them—not the originals, but reprints. Soon after I moved to New York, RAW magazine started, and that was really a revelation—seeing that there were all these other artists who were out there in the wilderness and interested in the same kind of things I was, doing these absolutely independent things. There was a movement afoot.

BLVR: How did you start writing serialized comics?

DC: I drew in my spare time while I was trying to get illustration work besides Cracked magazine to make a living. So just to keep from going insane, I drew this comic strip. I’d kind of given up on the idea of doing comics, because there was no market for it. There was RAW and Weirdo, but I didn’t feel that this was a career possibility. So I did this Lloyd Llewellyn story and sent it off to two or three publishers and never heard back from anybody. But I got a call, maybe a month later—I’d totally forgotten about it—and it was this guy Gary Groth from Fantagraphics, and he said, “Hey, we’d like to do a comic of your Lloyd Llewellyn thing.” He was offering me what I was envisioning doing way down the road, after jumping through all these hoops, and I was totally not prepared for it. He wanted a bimonthly comic and he wanted it to be all Lloyd Llewellyn.

So here’s this character I’ve never thought about beyond this twelve-page story, and all of a sudden I have to fill up endless pages with this guy. And I said, “Oh sure, I can do a comic bimonthly.” That was insane. I just sat in my room fifteen hours a day, thinking, What do I do next? I did that for two years and did six issues. Right at the same time that that ended, I got divorced from my first wife, and I wondered, What am I going to do now? So I thought that I should do the exact comics I wanted to do all along and not think about anybody else. I don’t care if anyone reads this. So I did Eightball.

II. “ALL IT TAKES IS ONE NUT.”

BLVR: In 2007, you wrote Mister Wonderful for the New York Times Magazine. Did you enjoy doing a weekly strip?

DC: About four years ago or so, I had open-heart surgery. I had a year and a half where I was barely able to work at all. I didn’t do any comics for that whole period, so I really needed something to force me to get them done. Usually when I do comics, I just do it and turn it in. I don’t have any deadlines at all. So I really felt that I needed a deadline to get me back to work. That was the reason I agreed to do it, because it’s not the sort of thing that appeals to me: having a deadline where I can’t keep fixing things and making things better and better, holding on to it until it’s perfect. But it was good: it forced me to think and get it on paper as quickly as I could and really get back to work. The Times isn’t really set up for fiction. Their style book is very much for news reporting, so it’s all stuff that doesn’t quite make sense with dialogue. They’d correct my slang; they’d say, “Oh, you can’t say, ‘She handed him a lit cigarette.’ You have to say, ‘a lighted cigarette.’” They were very prissy and fussy. As the strip began, they let me get away with certain things. I could have a character say “Jesus.” That was the one thing I had, so I really used it quite a bit. And then after eight episodes, some disgruntled fundamentalist wrote to them and said, “We really object to your use of the word Jesus.” So they called up and told me I could never use that word again. Right in the middle. All it takes is one nut and that’s it. I kind of wish it had happened at the beginning, because it actually made my writing much clearer. I was relying on Jesus as this catchall crutch of exasperation, and then I had to think about what it is he’s trying not to say. It was sort of helpful to the writing, but it’s awkward that all of a sudden he stops using his catchphrase.

BLVR: Adrian Tomine has described your work as being a distinct influence on his own and named you as a mentor. I also notice elements of your style in the work of younger artists. How do you view your position now as a member of an elder generation of comics writers?

DC: Adrian was a special case. When I first moved to Berkeley, Adrian had been sending me his comic strip for a few years, and I always thought he was maybe five or six years younger than me. (When I first moved there, I was about thirty-one, and I figured he was twenty-five.) He sent me one of his minicomics, and it had photos of him on the cover—which is hard to imagine him doing nowadays, Mister Modest. I had it lying around and my wife, who was going to Berkeley at the time, came in and said, “That guy’s in my class.” And I said, “No, he’s not. He just looks like someone in your class. He’s too old to be at Berkeley, there’s just no way.” So then, of course, the next day in class, she went up to him and said, “Did you send my husband a comic?” And we wound up becoming friends. And of course it turned out he was like eighteen or nineteen and had been sending me his comics when he was like fourteen. He really knew nothing about the trade secrets of drawing comics, and, for me, it was fun to be able to tell someone how to do stuff I had learned only by trying everything and failing miserably.

BLVR: You’ve mentioned in the past that you refuse to relinquish control of the artwork in your books and that you take great pride in having created each line. How difficult was it to take Ghost World, in which you drew every line and wrote every word, and offer it up for a collaborative film project?

DC: You have to realize that even the greatest auteur in film can’t have absolute control. It’s a medium that doesn’t allow for that. Immediately, when we started to work on Ghost World, I saw how you lose control right away, even in the very special case that Terry [Zwigoff] and I had, where we had a very sympathetic producer and we were allowed to do pretty much exactly what we wanted. We didn’t have a studio involved at all. But just to tell the set designer what you want, it’s almost impossible to communicate. I’m used to drawing a picture and getting it exactly right. And to try to explain Enid’s room was like banging my head against the wall. Finally I had to do the set dressing myself because they were getting it so wrong. These people are trying so hard, and they’re working sixteen hours a day, and they’re chain-smoking and drinking coffee all day, and they’re like, “We want to make you happy.” And then they get it wrong over and over again and you just want to go, “Oh, that’s fine. That’s fine.” I found myself doing that. You just can’t make a film that’s 100 percent your vision. I have to think of it as something that’s very different than what I get out of creating a comic.

BLVR: Did you write Ice Haven in response to your experiences with making films?

DC: That was the idea. I wanted to do something that was pure comics. The thing that I was so jealous of in watching the film being made was how much you could change the story in editing. It’s like writing a novel: You can move paragraphs around and delete characters. You can do anything, just keep revising. You cannot do that in comics. It’s impossible. The way the panels are in a grid, you can’t move them over and insert something else, because the whole page falls apart. You’re stuck with it. And that’s part of the beauty of comics—that it has a sort of spontaneity because you can’t revise it, really. But I was trying to come up with something that would allow for a certain amount of revision, at least moving scenes and things around. I thought if I did these little short stories, no more than two or three pages, if the sequence was off, I could move them around, switch them out, things like that. And that was what I got from the film in terms of how I did Ice Haven. But really, I was trying to do the opposite of film as much as possible. I was doing something totally controlled.

BLVR: What’s your relationship with Robert Crumb? There are so many characters in your stories that seem slightly reminiscent of him.

DC: He’s a hero, certainly, and I think he’s the greatest cartoonist who ever lived. Without a doubt. I’ve gone through phases where I can’t stop looking at his work for days and days, and then over the past six or seven years, I haven’t looked at his work at all. I knew it too well. But I’m sure that in two years, I’ll pull out his sketchbook and for the next few weeks, I’ll re-read everything he’s done. His influence is so ingrained in every cartoonist that came after him. When I hear cartoonists saying anything negative about Crumb, how he’s overrated or something, I know they don’t realize that he’s part of their DNA, that he’s invented everything they’ve done.

III. “A SELF-PERPETUATING SITUATION”

BLVR: I’ve heard that you’re working on a screenplay of the true story of three boys who re-created Raiders of the Lost Ark shot by shot.

DC: I actually wrote a script, but anything related to Raiders of the Lost Ark is a legal nightmare. It was a tough one because it had to be made by Paramount, who owns the rights to Raiders of the Lost Ark, or we could never have referred to the meta-text of the film.

BLVR: How did you settle on the story?

DC: There was an article in Vanity Fair in 2004 about these kids who made their own version of Raiders of the Lost Ark over the course of ten or more years, starting in 1984. It was just a crazy story, and I desperately wanted to see their film. Then one day, out of the blue, I got a call from a producer who wanted to meet with me about writing their story.

BLVR: Was the structure of Wilson influenced by doing the weekly strip for the New York Times?

DC: It was. As I was doing that strip, I was kind of studying comic strips and looking at different ways strips were done, and there’s something about humor strips, especially Peanuts. If you read them all in a row, in a volume, Schulz is just trying to do jokes, he’s just trying to be funny every day, and that’s his only goal. Every once in a while, he’ll get into something that yields four or five jokes—I doubt there’s any more than five or six in a row about one subject—like maybe Christmas. And then it moves on to Valentine’s Day and then it’s the summer, and you get a feeling of progression, as though there’s some kind of plot underneath all these jokes. I thought that was an interesting way to tell a story, a way that we’re all kind of familiar with. I thought, What if I told this story through a series of jokes, using the moments in the story that are funny and ignoring the moments that don’t fit into that, and letting the reader fill in lots and lots of missing terrain in the story?

BLVR: You’ve said you really love the format of the comic book but that there’s no real market for it anymore. In doing the strip format in a book, does it still feel like you’re getting to do individual comics?

DC: After I finished “Death Ray” [which was in an issue of Eightball that came out after Ice Haven], I thought that was it for comics somehow, for that format. I felt like I had done what I wanted to do and that the format was somehow obsolete—in that, to go back and do something in that format would seem like an affectation, like releasing a song on cassette or 8-track tape. It seemed cute. When I first got into comics, my original goal was to do books; I was really intrigued by that idea. Then I got into doing underground comics and got swept up in that. I like comics in book form, and the Peanuts books that I’m really connected to are the ones that came out in the ’60s that are called, like, You Need Help, Charlie Brown. They were annual reprintings of the best strips. That’s what I was going for with Wilson, a kind of collected comic strip.

BLVR: Is writing episodes for TV akin to writing serialized comics?

DC: That’s how I started out, writing serialized stuff where I didn’t really know where it was going. Like the Velvet Glove story [Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron], that was really the kind of thing I would love to do on a TV show, where you keep yourself as interested as the audience. I try not to know exactly what the end will be. I have an ending in case I get stuck, but I try to start out writing a character and a situation that I know will keep me interested for a while. I’m trying to come up with a self-perpetuating situation. That’s what you look for in a comic strip. Charlie Brown always has this frustration and alienation. Krazy Kat is always getting hit with a brick and is involved in this weird love triangle. It’s something you can do in different shades forever.

IV. “A SPIRITUAL CONENCTION TO PEANUTS“

BLVR: Wilson shares many formal qualities with Ice Haven, most significantly the comic-strip structure and varying drawing styles. In Wilson, however, each strip keeps to a single page, with a standard sixor seven-panel grid.

DC: The basic idea for Ice Haven was to take an old Sunday newspaper and turn it into a grand narrative, where Prince Valiant and Henry are interacting in some way, where all the characters kind of know each other in this larger world. In Wilson, I was using the different styles really at first kind of unconsciously, but toward the end I realized that that’s a good representation of human life: We have these various shadings represented by various styles that are not all that far off from each other; they’re all within a certain range. On a day-to-day basis, things shift, and we’re slightly different people. I really was exploring the idea of trying to construct a joke out of every scene in a life in a way that would piece together into a narrative.

BLVR: It’s certainly true of both Peanuts and Wilson that jokes overlay very profound, existential issues.

DC: That was the idea. I wanted it to kind of gloss over these profound issues. Wilson is an archetype, but he’s still dealing with the stuff that I certainly deal with, although in a very different way. When my wife was first reading it, she said, “Wilson is like an everyman version of your constant nemesis in your daily life.” I’m always coming home from a café, where I’m trying to write, and I’ll be like, “This guy was just driving me crazy and he sat down at the same table as me and was boring me with his stupid stories.” It’s always a Wilson-type guy. But then I had to admit that part of my anger about that guy was that I admired him. They have this sort of outgoing personality where they’re communing with their fellow man, and they’re trying to make connections to random people in a way that I find admirable. So I had to reconcile that: in a way he’s my enemy, and in a way he’s my avatar.

BLVR: But Wilson never really makes connections. He’s so self-involved, so narcissistic. He talks to people but doesn’t seem to expect a considered response.

DC: No, that’s part of that type. And that’s his tragic flaw: he can’t quite figure out how to navigate relationships.

BLVR: How aware were you of Peanuts’s influence on this book?

DC: The way the story began, my dad had cancer and was in the hospital—it was the end. So around March 2008, I was in Chicago in a depressing suburban hospital, sitting in the room with him. I had been there for weeks and I had just gotten David Michaelis’s biography of Charles Schulz, and I read that, and Schulz’s life was very oddly parallel to my dad’s: My dad grew up in Pittsburgh, and Schulz grew up in Minnesota; they were the same religion, went to the same kind of church; had very similar affects. My dad always reminded me of the way I imagined Schulz to be, and it was proven by this book. I had a deep connection to what the book was all about, so I felt a spiritual connection to Peanuts at that moment. In the book, Schulz says the difference between a professional cartoonist and some amateur is that a professional cartoonist can just sit down and in five minutes he’s got a workable gag for a daily strip. So I sat down and started writing strips without really thinking about who this character was. He just popped out of nowhere, and I wrote strip after strip after strip. It got so that I wasn’t even drawing, just writing word balloons, and I found I could endlessly write strips about this guy, this obnoxious guy. By the end of this couple of weeks, I had an entire sketchbook filled, hundreds of pages of jokes.

BLVR: Where Charlie Brown is a sympathetic antihero, Wilson is harder to pin down. Just when he’s at his most pathetic and we’re ready to soften toward him, he says something snide. It’s difficult to side with him, and this complicates not only the idea of disliking and feeling distanced from the book’s main character, our guide through the story, but also wanting, in fiction, to find truths that we can hold on to.

DC: I like that terrain, when you have a character that isn’t likable, the kind of person who in real life you try to avoid. But you’re stuck with him, so you’re searching for a shred of humanity. I think as a reader you’re searching for a way to like this guy. I would hope that by the very end, you’ve found a little something. I certainly felt that, when I’d gotten to the end of the story, he had a certain humanity that I have to admire. He’s figured something out.