“Why not fashion?” David Altmejd asks me.

Why not, indeed? I’m a fan of fashion; he’s a fan of fashion. So when I went to interview him about the spectacular sculptures he creates, we decided that fashion would offer a fine entrée to a conversation. Fashion feeds his work. Clothing, jewelry, and wigs pop up in his sculptures. Birdmen sport natty suits. Rhinestone flowers sprout from the corpses of werewolves. Gold chains swarm like insects through mirrored counters and cabinets. The fashion world furnishes him with many of his materials; he transforms them into the flora and fauna of a world that’s entirely his own design.

It’s small surprise that fashion designers—Marc Jacobs and Raf Simons, to name two—admire his work. But they’re not alone: his art is both original and engaging, critically acclaimed and crowd pleasing. At thirty-seven, he is an artist of international stature, his work collected by the Whitney Museum, the Guggenheim, the Dallas Museum of Art, and the National Gallery of Canada, among others.

Altmejd was born and bred in Montreal. He started his studies at the Université du Québec à Montréal, then completed them at Columbia. Though he has been in New York since graduating, he still speaks with a francophone accent. He apologizes for his English, but he shouldn’t. He speaks well. Better still, his ideas are as idiosyncratic as his sculptures.

I met him almost a decade ago. If fashion is the framework for our interview, so, too, has it been a framework for our friendship. We talk about style. We go shopping together. He has much nicer clothes than I do. In my novel The Show That Smells, fashion icons Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli battle for the soul of a country singer. Altmejd created the novel’s cover art, a crystal-encrusted werewolf head with tufts of shocking-colored hair. For those who know fashion, the cover makes it clear: Schiaparelli wins.

—Derek McCormack

I.ART IS A BROOCH THAT YOU WEAR ON A BLOUSE

THE BELIEVER: Years ago, when we first met, we walked around midtown Manhattan looking for costume jewelry for you to use in your work. You bought a brooch with the word ART in rhinestones. What happened to that?

DAVID ALTMEJD: I don’t think I used it. It would be too obvious.

BLVR: Still, it would look perfect on a blouse, don’t you think?

DA: It depends on what blouse, and who is wearing it. It would be cool on an older lady.

BLVR: I’m an older lady. Can I have it? [Laughter] I mention the ART brooch because brooches, and jewelry in general, play a big role in your work.

DA: I really use a lot of jewelry.

BLVR: I’m fascinated by the way your work incorporates clothing and jewelry. I’m fascinated, too, by the way it plays with display and merchandising principles— plays with them and perverts them.

DA: I’m interested in display, though it’s not the main aspect of my work. It’s an aspect among other aspects. I’m not even against the idea of using the same sort of strategies as stores. I’ve never really taken things from a store display; I mean, I’ve never walked into a store and thought, I’ll do that, I’ll do that. I just end up using the same strategies that stores do. I feel as if I do it instinctively.

BLVR: Where do you find your jewelry?

DA: I used to go to these wholesale stores where they hand you a basket when you walk in. You could buy a brooch for two dollars. I don’t buy jewelry pieces anymore; instead, I buy the parts of them: the chains, the stones. It’s more like I take the parts and put them together my own way.

BLVR: Do you ever incorporate precious jewels in the work?

DA: No, it’s costume jewelry. I do use real crystals now, though, real rocks. I will use real amethysts. But precious stones, no—I don’t need a diamond, I can use a fake diamond. It’s not how much it’s worth that matters, it’s the effect.

BLVR: How about when galleries or museums stage shows of jewelry? Does that interest you at all, the work of jewelers?

DA: I am interested in beautiful artifacts, of course. I’m not so interested in the history part of jewelry, the chronology of creators and what was made. I like individual pieces. When I’m really working on something, I feel as if I’m a jeweler making jewelry.

BLVR: When you’re constructing a sculpture, what dictates where a piece of jewelry will go? Is it a sense of rightness?

DA: It’s symmetry. I like things to be symmetrical, or at least balanced. Since we’re talking about fashion, I will says this: it’s sort of like a designer staring at a model and putting that final touch to her outfit, that final accessory, and saying, “That’s it!” [Laughter]

BLVR: Can jewelry be art?

DA: Yes, I think so. It’s more likely to be art than fashion is. I can see a jeweler completely absorbed in his work and forgetting about what the purpose of it will be. It seems like a fashion designer would always be thinking of what the final result will be, which is people wearing his clothes.

BLVR: Can fashion be art?

DA: It’s a different game. Fashion is much more respectful of taste. Even if it pushes boundaries, it’s always tasteful; even when it tries to be distasteful, it’s tasteful. In art, it feels like you can push it further.

BLVR: A designer can do something outrageous, but he still needs customers who want to wear the outrageous clothes, and who can pay for them.

DA: I think the idea of cool is important in fashion; I feel that when fashion designers do something outrageous, it’s supposed to become cool right away. With art, there’s the hope that it will remain outrageous or shocking, at least for a while.

BLVR: Fashion works at a frantic pace. The most shocking look is meant to be recuperated at a ferocious speed. Art, too, can be recuperated right away, too, but sometimes it isn’t; sometimes it stays difficult and unsettling for a while.

DA: I feel like art is different; it’s so conceptual, in a way, that it lets you do anything, whereas fashion is not really conceptual. When it says that it is, as with Hussein Chalayan, it’s not true; it’s really a style, it’s “the conceptual” in quotation marks. It’s the look of “conceptual.” I’m sorry, sometimes there are moments when my English is really, really bad.

II. WEREWOLVES DON’T WEAR SILVER PINS

BLVR: I met you in 2004, when you were in the Whitney Biennial.

DA: You wrote an article about me and called it “Hairy Winston.”

BLVR: That was about the time you bought the ART brooch. I thought it might wind up in a werewolf sculpture. I thought, Don’t put a silver brooch in a werewolf!

DA: I didn’t.

BLVR: At that time you were making sculptures with decaying werewolves. The werewolves were covered with costume jewelry and crystals.

DA: Jewelry, because it’s shiny, it vibrates visually; I see it as something that has a little pulse. If you place it on something that’s obviously dead, it’s going to seem like a strange organ that generates real energy.

BLVR: The werewolf sculptures weren’t really about dying and decay at all; they were about alchemy. Jewelry and crystals were somehow produced by the processes of death; they were growing. They were magic.

DA: Maybe it was magical. I like to think of it as physical, as biological. The jewelry plays a part in the transformation. Gold chain, for example, I use to connect elements. I see it as a way of making energy travel from one point to the other.

BLVR: It’s the energy, but also the conduit. The jewelry refracts and redirects energy, but it also consists of energy. It’s playing different roles in different situations. I love that, I love that its functions can change so fast. I also love that the jewelry doesn’t have to be a diamond; it can be some dumb dime-store rhinestone.

III. THE SLOT IN A BOX THAT A RING SITS IN

BLVR: In 2004, at your first solo show at Andrea Rosen Gallery, there were lots of werewolves and jewelry. The show seemed to me to be at least a little bit about jewelry display.

DA: I remember a sentence you told me, something that you were going to put in your book. You said the slit in the head of a penis was like the slot in a jewelry box that a ring sits in.

BLVR: That line’s your fault. In that first show of yours, dead werewolves were doing all sorts of sexual things. No, it had werewolves who had died doing all sorts of sexual things. Or were they dead? I don’t know. They were covered in gold chains and costume jewelry and they were lying in incredible mirrored boxes and on counters.

DA: How do you activate an object? If you’re given a werewolf head, how are you going to make it feel precious? For a really long time, that was an important part of my work: to position them in such a way that they would vibrate. I don’t think there’s an infinite number of ways.

BLVR: I know that the chains and jewelry were acting as energy, and it made sense to me to think about retail: there are few places more fraught with energy and desire than store counters. I don’t know what kind of store sells dead werewolves, or uses them as jewelry trays.

DA: I don’t know.

BLVR: You were saying?

DA: If we think of the idea of activating an object, how do we do it? If you place it on a table, right in the center to make it look important, yes, people are going to think about store display. Throughout history, how did churches display sacred objects? A little bit the same way. It’s not necessarily about store display; it’s about making something seem precious.

IV. THE CHANGE ROOM CHANGES YOU

BLVR: At the 2007 Venice Biennale, you used mannequins in your sculptures.

DA: Yes, but I haven’t done it very often, only in that piece. And they had bird heads.

BLVR: I think it was the first time you incorporated clothing into your sculpture, wasn’t it?

DA: A couple of the werewolves I made years ago had underwear and shoes. I made the underwear dirty to make sure that it was sort of decaying with the body, becoming part of the body. It was involved in whatever transformation was happening with the body. I wanted them to wear a specific brand of underwear, which was 2(x)ist. It’s a popular brand: if you go to a department store, you have a choice between Calvin Klein, 2(x)ist, and Hugo Boss. I wanted to allude to existential ideas, but through underwear. [Laughter]

BLVR: The mannequins in Venice couldn’t help but conjure a retail space, at least in my mind. Not the men’s department, but the birdmen’s. Do you like mannequins?

DA: I don’t think I’ve ever loved a dress or piece of clothing that was worn by a mannequin. I never stop at a store window to look at what mannequins are wearing. It’s dead. It’s not cool if it’s worn by something dead; that’s just my opinion.

BLVR: So with the mannequins, did you mean to convey a degree of deadness?

DA: If I had them wear clothes, it was sort of to make them seem more alive. It sounds contradictory. Putting a mannequin under clothes won’t make the clothes look more alive; putting clothes on a mannequin makes the mannequin look more alive.

BLVR: Did you dress the mannequins in any particular designer’s clothes?

DA: I don’t remember. I used some new clothes and also some used ones. I didn’t want them to look too much like they were in a store window.

BLVR: There was one bird-headed man in a booth that contained crystals and mirrors. It seemed to me to be a change room. Maybe he was trying on clothes, maybe he was changing from man to bird, or from bird to man. I considered that it could be a confessional booth, but it’s mirrored, and that’s really a retail thing.

DA: The mirrors are cracked and shattered. There are a lot of mirrors in stores and in displays, but you don’t look at yourself in them; it’s not like the mirror is a focus that puts you at the center. Of course, the mirrors on the walls are there for you to look at when you try your pants on. The mirrors that line counters and are on columns are not looked at. Mirrors are materials that move and that multiply space and that vibrate visually. Do churches use mirrors? If I were to build a cathedral, I would place mirrors everywhere in it.

V. BEES ARE NATURE’S BROOCHES

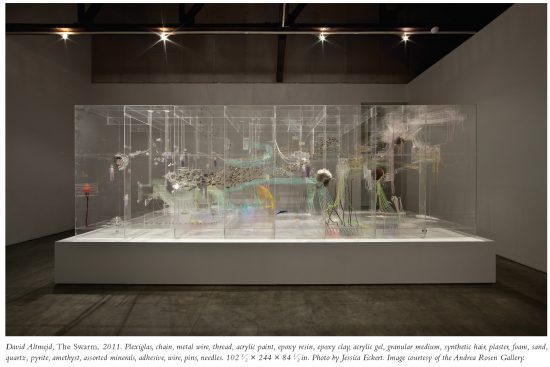

BLVR: The Vessel and The Swarm, a pair of huge sculptures, dominated your 2011 show at Andrea Rosen. They were giant Plexiglas boxes filled with insects, plaster hands and ears, and yards of thread—thread fanning out, rising and falling, doubling back through holes, wrapping around shelves and objects. Was this the first time you used thread?

DA: There are a few pieces that I made previous to the show that used thread, but, no, I had never used it a lot before. It came about as an alternative to gold chain— the pieces you mentioned earlier, the big Plexiglas boxes with webs and networks of gold chain. I started using thread as a way to introduce color.

BLVR: You dyed them?

DA: Yes, some of them have a gradation of color. I painted them. I painted a bunch of threads with very diluted acrylic to create gradations that I wanted.

BLVR: The bees and the jellyfish you made from thread and Plexiglas—those struck me as the closest thing to jewelry I’ve seen you make.

DA: I really liked the insects. They are positive insects, insects that give. Not like ticks; ticks only take. I’m into using things that give and give and give: things that are generators. Bees give and pollinate flowers. Oh, it sounds so cheesy. [Laughs] I want everything in my work to generate. I want everything in my work to be generated inside the work. If there’s gold chain, I want it to be coming from something, so I need a generator of gold chain at the beginning of the gold-chain segment; it has to be coming from something that generates gold chain. It has to be coming from somewhere. That’s why I used those little Plexi bees, the chain-generators. If there’s thread, it also has to be generated by something—that’s why I like spools. There were a lot of spools in that show as well, because they’re thread-generators.

BLVR: What generates the spools?

DA: The spools are all handmade in Plexiglas. They’re the same material as the box. In my mind, they’re a mutation of the Plexi box that contains them.

BLVR: When I saw those Plexi boxes, I thought, It’s offering a cross-section of what’s happening in the gallery. There’s always something happening, even if it’s invisible. You made a box that lets us see what’s happening all the time in secret.

DA: The purpose of the box is as a support structure to give me the chance—because it’s transparent, invisible— to attach things and make them seem like they’re floating.

BLVR: The spools are the same Plexiglas as the box: it’s as though you had something rare and put it in a display case or window, and the case and window started generating what was inside it.

DA: I like those shifts. I like to use something as a frame, and pretend it doesn’t exist, then all of a sudden it starts to exist. In one of the pieces, I pretended that the box was just an invisible support, and that the Plexiglas structure that I added inside did not exist. In terms of one specific narrative, the Plexi isn’t there, it’s simply a support. At the end I added some ants, and the ants started walking on the Plexi. For me, that was the moment when the structure started existing. They’re not ignoring it. They’re using it to get around. Again, from the beginning, the box doesn’t exist, but it does sometimes. I like to go from pretending it’s not there to using it and then going back to pretending again.

BLVR: It showed in the work, because it was like you were viewing an exhibit, but then you’d notice that the Plexi was fractured and it was participating in the piece.

DA: I liked the fractures in it. It’s participating in the process of creation. I see it as something playful.

VI. THAT NECKLACE IS WEARING YOU

BLVR: If jewelry can function that way in your sculptures, does the shininess function the same way on people?

DA: I think that jewelry offers transformative powers. I’m really interested in the positioning of jewelry on people. It’s not random. It’s not random, for example, with a necklace. It hits right in the center of the chest.

BLVR: Jewelry is close to perfume: it’s worn where you would wear perfume, behind the ears, on the wrists, at the base of the throat. Where there’s heat and blood.

DA: Yes, but you don’t need heat to make jewelry glitter, you only need light. I think it has more to do with the fact that they’re on sensitive areas. It’s the same with the bindi: it’s in an amazing position. Earrings—I question the importance of that. Do you think that’s a good placement? Lip piercings, I think, are an abomination. They show a total disrespect, or lack of care. They’re lazy. There’s nothing that happens there. There’s something too soft about the lips. Often when there’s a piercing there, it’s not in the center, it’s off to the side. I think tongue piercings are interesting—I mean, I don’t like them, because they make me feel pain.

BLVR: Perhaps that’s what some people want to do with their piercings: to make other people say, “Ouch, ouch, ouch.”

DA: I don’t have any piercings; I don’t think I could have any. I can imagine wanting a piercing if I wanted to take control of my body. “David, your body is just skin and flesh, you can pierce it, you’ll see, you’ll feel you have control over it, it’s not a bad deal. Don’t worry, David, you can do what you want.”

BLVR: You’ve never felt the need to get control of your body that way?

DA: Maybe it would be an amazing feeling.

BLVR: You don’t wear jewelry.

DA: No, but I like the idea of wearing it. I don’t wear it, probably because I feel like it’s underlining my body. It’s making it obvious that I have a body. If I wear a necklace or bracelet, it’s going to be like saying, “Hey, look at me, I’m here.” It would make me uncomfortable.

BLVR: It makes you uncomfortable that people would see that you are not invisible. Invisibility is important to you.

DA: It’s not that it’s important to me, it’s simply a fact. I have always felt invisible, ever since I was a child. I mean, I know I am visible to you, but to most people I am not. I can walk down a street and not be noticed.

BLVR: That’s a terrible feeling for a child to feel.

DA: It was hard. I always had the feeling that I would grow up and have—I don’t want to say revenge, because that’s not it. I had the sense that I would show everybody, you know? I think that because I was invisible I could go anywhere and nobody would care. It was an opportunity to think and to become critical.

BLVR: And you still feel this way.

DA: Absolutely.

BLVR: So jewelry would compromise your invisibility? It would be akin to the Invisible Man putting on a bow tie?

DA: I would be invisible, but people would notice the jewelry. Jewelry has no purpose other than to be noticed. It’s always an exclamation. It’s always showy.

BLVR: What about clothes, then? How do you decide what to wear?

DA: Clothes are different than jewelry. Clothes can either draw attention or they can make you invisible. I always wear things that accentuate my invisibility.

BLVR: How can clothes accentuate invisibility?

DA: Well, it’s a matter of avoiding things that are trendy. In terms of color and cut… [Pause] Oh, I have an honest answer, but I’ve never talked about these things. I have codes, I have systems, but I don’t know if I can put them into words.

BLVR: I think a lot of gay guys develop ideas like yours as boys, that they’re invisible or monstrous or evil in some way. Me, I would rather be invisible than be disgustingly ugly, which is what I’ve always been.

DA: You have never been disgustingly ugly!

BLVR: You have never been invisible! It’s difficult for me to comprehend all this, David, seeing as you’re so good-looking. You have sex, David; you have boyfriends. Men notice you. Men see you.

DA: I don’t believe they do. It’s always dark when I meet them. [Laughter]

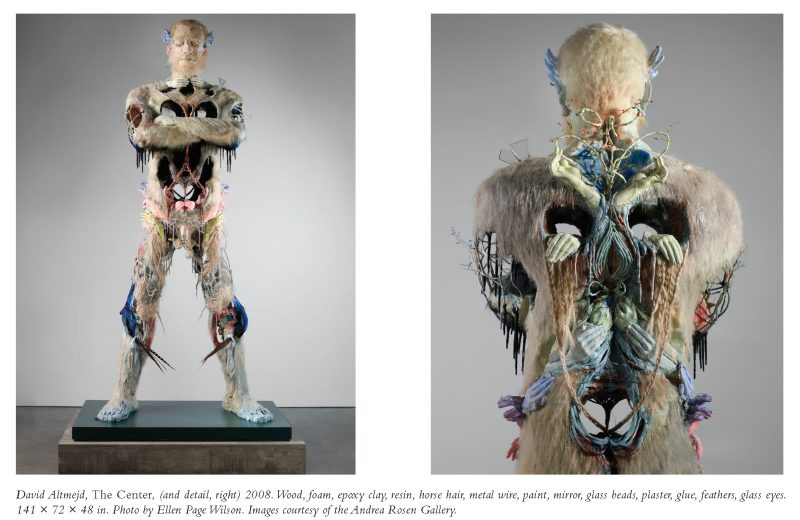

BLVR: I can’t help but think of your 2008 show at Andrea Rosen, which featured colossi. These were giant statues, David, giant figures.

DA: Yes.

BLVR: You’re invisible, yet you build statues of yourself that dominate the gallery. And some of them were made of mirrors, though they didn’t function as mirrors: they somehow demanded and deflected attention.

DA: That’s why I’m a sculptor. I think that it’s very satisfying to make sculptures so that I can create things that aren’t invisible. My physical and visual anchors in the world are my sculptures. The mirrors in the figures were sort of deflecting attention, which was a different level.

BLVR: It must be very unnerving when people criticize your work.

DA: But at the same time, there’s something really satisfying about it—it’s a reminder that I exist. I mean, no one would ever criticize me or my body, because I’m invisible. It would never happen. It’s amazing to know that I really exist in the world through those sculptures.

BLVR: They represent you, but you also understand that they’re stand-ins for you.

DA: I can’t back away from them. I don’t want to. I don’t like seeing that. I like being aware that people are looking at my work, but I don’t want to see it happening. It gives me a sort of vertigo. It’s not supposed to be like that. It would be like being outside of my body and seeing people looking at it. It’s embarrassing.

BLVR: So your sculptures are you; that is, they are visible, tangible things that allow you to have a visible presence. You have taken all sorts of shapes: decaying werewolves covered in crystal, mirrored mazes, bird-headed men, Plexiglas boxes that contain ecosystems of thread and insects. All these Davids wear jewelry, though you do not; all these Davids are showy, though you are not. The boxes are invisible structures, though they can become visible. I could describe you the same way.

DA: Yes.

BLVR: The sculptures are always bursting with life. The energy—your energy—doesn’t die; it’s always pulsing and mutating.

DA: I’m wondering if with time it will change. I can imagine a piece so dusty that the energy will be held inside. What happens if the jewelry gets tarnished? What if it doesn’t shine? Does it mean that the piece is dead? Does it have the same power? Is the magical aspect only connected to the shininess?

BLVR: Who in the world would let their David Altmejd get dusty?

DA: I’m not worried. I don’t think that dust can kill anything.