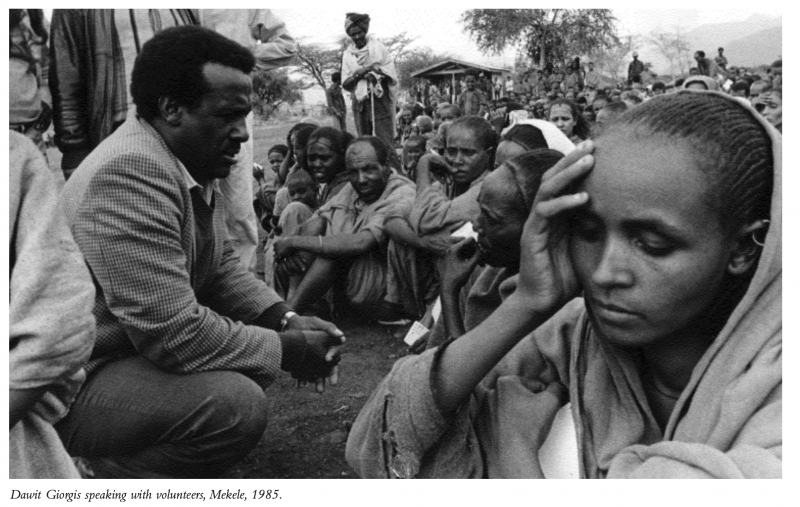

During the Ethiopian famine of 1983–1985, when more than a million Africans starved to death, Major Dawit Giorgis was the presentable face of the Marxist-Leninist junta that ruled his country. He was on TV all the time. The prime-time audience would listen to “We Are the World,” and watch images of stick-limbed children, and then Dawit would smile and ask for donations. At the United Nations, he reassured members that aid and food were saving lives. He was often photographed with Bob Geldof and Mother Theresa. He was young, handsome, and spoke excellent English.

He was also an ambitious ideologue. Dawit was born into the ruling elite of Ethiopia; his father was Emperor Haile Sellassie’s first vice-minister of information; and he served in the emperor’s army. But education at Columbia University radicalized him, and when a gang of junior army officers overthrew the emperor in September, 1974, he rushed home to take part in the revolution. For eleven years, Dawit was a member of the Dergue, the governing Provisional Military Administrative Council. He was, successively, deputy foreign minister, governor of Eritrea, and finally chief of Ethiopia’s Relief and Rehabilitation Commission. He was a cautious ally of the Council’s leading light and Ethiopia’s dictator, Colonel Haile Mariam Mengistu—until the day in 1985 when Mengistu turned his fickle eye on him, and Dawit defected to the United States.

In the following years, Major Dawit went to ground. He wrote a self-justifying autobiography while at Princeton University; he joined the Ethiopian opposition in exile; and he worked for the United Nations in some of Africa’s worst conflicts. But he disappeared from the public eye.

This last winter, I found Dawit in Simon’s Town, south of Cape Town, where the houses tumble down a steep, windy promontory into the sea. I wanted to ask him if he felt culpable for the radical dystopia the Dergue had constructed in Ethiopia, and if so, how much. But Dawit is only partly “reconstructed,” to use the jargon of the 1960s: he is still sentimental about revolution. We drank tea. His speech is courtly, circumspect, and chaste.

—Jason Pontin

DAWIT GIORGIS: On September 14th, 1974, Ras Tafari, the Emperor Haile Sellassie, was deposed. It was the most important moment in my life. I had left the emperor’s army in 1968 and won a scholarship to study law at Columbia University. I said I would never go back to Ethiopia unless things really changed. I was living in Texas, working towards a PhD at Southern Methodist, when I heard there had been a coup d’etat in Addis Ababa. I hurried home. I left everything: my studies, my fiancée, everything. I was ready to go and die. I left with absolute joy.

This was years ago. It’s difficult, maybe, for a younger generation to understand the glamour of socialism in those days. But when I was young, it was very popular to be a Marxist. Every evening, uptown in Harlem, there were meetings about Cuba or China, and everyone was waving their little red books and discussing politics. We wore beards and army fatigues. Memories of the civil rights movement were still strong. It was so popular to be anti-American, to be anti-Vietnam, to be anti-capitalist. The Soviet Union for us was the model of progressive change. Lenin was a hero. Che Guevara was a hero. We even defended Idi Amin. We thought that the end of capitalism was coming and we wanted to be at the vanguard of the struggle.

But, still, I was different from my friends in the student’s movement. The plain truth was, I was ambitious. I was ambitious to play an important part in Ethiopian politics. The revolution was an opportunity for me. Because the military had taken over, I could play two roles. I knew most of the members of the Dergue. Some of them were my friends. So I could be a student to the army and an army officer to the students.

Today, people say that they were forced to join the revolution, but I was never forced. I went to Ethiopia not only to change Ethiopia, but to change the wide world. I thought that Ethiopia might be a model for all of Africa.

THE BETRAYAL OF THE REVOLUTION

The early high spirits of the revolution were soon dissipated. The Dergue chose General Amman Andom, a chippy nonentity, to be head of state—while Mengistu dominated the Council from the shadows. When Amman resigned his post, and demanded that the Dergue recognize him as Council chairman, Mengistu ordered him to be arrested—and in the resulting confusion, Amman committed suicide in full dress uniform, wearing all his medals. Then, Mengistu ordered the killings to begin.

Why did I believe in this stuff? Oh, I don’t know. Marxism is tremendously appealing in a poor country like Ethiopia. We wanted to build a classless society. What’s wrong with that? We thought the theories of Marx and Lenin had been amended by the experiences of Mao, Che Guevara, and Frantz Fanon, and that there was a shortcut to socialism. What’s wrong with that? We thought we could fix everything at once. We would have land reform, and the nationalization of assets, and we would build a truly egalitarian society. What’s wrong with that? It’s beautiful. It’s a very Christian idea.

What was wrong was, it didn’t work. You live through a revolution and you discover certain things about human nature. You learn what’s practical. It takes time to learn these things. Some of us learned quicker than others. Still, I think it’s good to have been idealistic at least once in your life. The generation now, they have no hope for future at all. They are unembarrassed by acquisition.

Things started to go wrong almost immediately. When I went back, I wanted to run the courts. I wanted to prosecute the emperor and his former officials. I was a lawyer, after all, and I thought, maybe I would be part of the prosecution. But instead, in November, ’74, Mengistu ordered the execution of fifty-nine members of the royal family and former officials of the emperor. I was really shocked. At some point I knew the revolution was going to turn bloody: I was not a fool. But I wanted the blood to be shed with the due process of law. If the revolution couldn’t be entirely just, I wanted at least the semblance of justice. I argued to the Dergue, “It doesn’t have to be exactly how they do it in Europe or America, but let’s have the appearance of justice, and we can still do things our own way.” But they didn’t listen. There was a group in the Council who really wanted to execute everyone. When they tried to arrest Amman, and he killed himself, they said, “OK. Let’s get busy. In for a penny, in for a pound. Let the world condemn us, because we are already covered in blood.” But it was a terrible night. Afterwards, it was never the same. There used to be a famous slogan and song in the early days of the revolution. We sang, “Without blood, without blood.” After November ’74, no one sang that any more.

Day by day, your idealism is slowly diluted. You become pragmatic. You see that things are not working as you hoped. Some things you give up, but there are principles you don’t want to lose. All of us in the government reached that point eventually. I compromised and I compromised, and there came a moment where I couldn’t go any further. For me, that point wasn’t the massacre of November ’74, or even the Red Terror in ’76 when men in goggles drove jeeps around the cities shooting at people; what soured me was Mengistu’s behavior during the famine.

RED STAR RISING

Dawit is honest enough to date his disillusionment to a period after the pogroms of the 1970s: he voiced no reservations about the Dergue’s methods at the time. In his autobiography, Red Tears: War, Famine, and Revolution in Ethiopia (Red Sea Press, 1989), he writes, “I was at first an enthusiastic participant in the ’74 revolution. I was caught up in its emotions, and caught up in its potential to improve life in our country.” From 1974 to 1983, he rose through the party hierarchy, occupying increasingly responsible positions, and disguising his growing reservations about Mengistu.

So instead of becoming a prosecutor, I went into the country. I joined the campaign, called the zemecha, that sent 60,000 students into rural areas. The students were to politically educate the peasants and teach them to read. I thought the zemecha was one of the bright spots of the revolution. Many students, particularly those from the elites, had never been to the countryside. Forcing them to go and live with the peasants was a way of educating them, too. You know, you go fifty miles out of Addis Ababa and it’s another world, almost another time.

All through ’75, I was the most jubilant person: in meeting after meeting I argued for nationalization of the land. For me, the happiest days of the revolution were when we nationalized the land. But then the Dergue complicated matters by combining nationalization with socialist agricultural programs.

We didn’t talk to agronomists about whether these programs would actually work. The Dergue didn’t want to hear any doubts. If you questioned any aspect of Ethiopian socialism, you were thought to be against the whole revolution. The resettlement program in particular was crazy. We said that we were moving people from overpopulated areas, but the agenda of the Dergue was quite different. Their goal was the depopulation of certain areas. Mengistu wanted to get rid of peoples who were a nuisance because they were protecting the rebels. He would quote Mao, “The people are a sea in which the rebels swim. Therefore, we must drain the sea.” Our agricultural programs were later very important, because they created conditions where a famine was almost inevitable.

I became the permanent secretary of foreign affairs because I screwed up. In one of my conversations with Mengistu, I brought up the subject of Ethiopia’s relationship with the rest of the world. This was in ’77. I stupidly told him that we were pariahs. So Mengistu said, “If you think you can do better, go give it a try.” Foreign affairs was a good school for me. At the United Nations I realized, “Oh, things are not as I thought.”

And then, in ’79, Mengistu sent me to Eritrea as the chief representative of COPWE [the Commission to Organize the Party of the Workers of Ethiopia]. That meant I was the civilian authority of Eritrea, its governor. I had absolute authority! If I wanted to round up one hundred people from the streets and execute them, no one would have stopped me. But if you ask any Eritrean today, they will still tell you, “Dawit is a hero.” I worked in Eritrea for peace and for unity. Most Eritreans never wanted to be independent. What they wanted was peace and prosperity. The three years I was governor were the best Eritrea ever had. Ask anyone. Today, of course, Eritrea is an independent country.

Mengistu removed me from Eritrea in ’83 because I was opposed to the militarization of the province. My authority as COPWE representative was always being undermined by the army. There could be no purely military solution to Eritrean political aspirations. After I expressed my feelings to Mengistu, he sacked me and sent me to run the RRC [Relief and Rehabilitation Commission], which was in charge of all humanitarian activities in Ethiopia. This was just before the famine. This is how I became known to the world—and enjoyed my little fame.

THE FAMINE

In 1982, the kiremt rains that fall in the Ethiopian highlands from June to September were very light. The main harvest was bad. In many places, the tef crop—a native grain used to make injera, the large, pancake-like bread which most Ethiopians eat—was inedible. The next year, the belg rains that fall in the highlands from February to April failed altogether. There was no second harvest at all. The failures of the 1982 kiremt and 1983 belg came after a decade of severe food shortages, and a century of bad governance. The Ethiopian peasantry had been stripped of assets like stores, seeds, and livestock with which they might have endured a decline in food production. Eighty-five percent of Ethiopians are rural peasants, dependent in one way or another on subsistence farming: with nothing to fall back upon, they began to starve.

I thought I would be left alone in the RRC. Mengistu hoped I would be quiet. But as soon as I got there, I began to hear the most alarming reports. People were dying in Wello, in Tigray, in Gonder—all over the north. I tried to tell the Dergue. Mengistu thought I was trying to cause problems. He believed that famines were normal in Ethiopia. He would rail at me, “Why, Dawit, why? Why are you telling us this? We need famines to trim the population. Why are you making trouble again?” We were preparing to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the revolution and he was angry at the distraction. He reminded me that I was a member of the Party and that my responsibilities were primarily political. But then a BBC crew came and photographed the devastation around a town called Korem. There was an extraordinary outpouring of grief and rage in Europe and America. Celebrities came to see what was happening. The relief effort became the most important fact in Ethiopia.

What was Korem like? I went there on a number of occasions during the famine. There was a regional food-distribution center there. Normally, this village had perhaps 3,000 inhabitants. But in ’83 there were more than 48,000 people in Korem waiting for food. There was a moaning over Korem. It was very disturbing. You hear about death, or you see it on TV, but it is a different thing to experience it, to be amongst people day in and day out when you are see they are dying helplessly. That is a very different experience.

I remember on one occasion there was a Japanese journalist sitting down and looking at a mother and two kids—and he was watching with his camera, waiting for her to die. I hit him, and I threw away his camera, and I screamed, “You are a horrible person.” Some people have the—I don’t know what you call it—the courage to do that, but I never had the courage to look at people dying.

But here is the worst thing. The people at Korem were survivors. They were the lucky ones. The first time I went there, we interviewed people, and they would tell us, “We are only a part of a family.” Everyone else had died on the way. It was very difficult to imagine that kind of suffering. Mengistu never visited these areas except for a very short visit, after the worst was over.

There have been many explanations of why famine is a recurring problem in Ethiopia. There is a standard explanation for famines: academics say they occur consequent to a natural or economic disaster, and in a context of underdevelopment or inadequate technology. But I think it’s different in Ethiopia. For fifty years, there has never been any emphasis by any Ethiopian government on rural areas. Successive governments have cared about different things. The emperor cared about his own dynasty. The Dergue was concerned with control and ideology. The current government has fought to hold on to Eritrea. But no one ever cared about the peasants. No matter who was in power, the military has spent 60 percent of the government’s budget. So how can we not have famines, how can we not have poverty?

There were some immediate causes of the ’83–’85 famine. The first was the agricultural policies of the government, all the socialist measures that we took that backfired so badly: the peasant associations, the fixed prices for products, the forced collectivization, the state farms. We assumed that our policies would create some dislocation, but that in time the attitudes of the peasantry would change, and they would become more selfless. We were trying to create a new kind of human being. He would be a member of the community first, and an individual last. But all our policies combined to discourage the farmer from producing anything. Second, the whole exercise of implementing a Marxist ideology in the model of the Soviet Union in Ethiopia created an incredibly negative response on the part of the international community. When the RRC reported that there would be a famine in Ethiopia, and that we required immediate donations of food and money, the international aid community hesitated. They politicized every issue. They didn’t trust us. They wanted answers to questions that the Ethiopian government could not answer. And there were other, proximate causes, like the war against the rebels.

THE ETHIOPIA OF THE MIND

The belg rains fell in 1985, and Ethiopians went back to their villages, but Dawit had become a tired revolutionary.

I cannot describe what it was like to serve in Mengistu’s government. Sometimes we turned a blind eye. Sometimes we invented rationalizations for ourselves. Sometimes we let the ends justify the means. We said, “So long as it is in the interests of the people.” The records are very clear that I was never part of any of the killings. But I was someone who watched. You could condemn me as some one who associated with a government that was criminal and obscene. In any case, I really felt bad when Mengistu and some of his people took steps to prevent the RRC from doing good humanitarian work.

For Mengistu what was most important was the image of the revolution. So many people died, so unnecessarily. I remember, during the celebrations of the tenth anniversary of the revolution, Mengistu mentioned the famine only once in a in a six-hour speech. This was during the most trying moment in the history of Ethiopia—when a hundred people were dying in every shelter every day and we had more than ninety shelters. These were lives that could easily have been saved. And in this speech, Mengistu refused to give more than five minutes to the famine. This person was really out of his mind. He was talking about the revolution, the revolution, the revolution.

Mengistu only believed what his cronies told him. Anyone who told him things he didn’t like was a political criminal. He really believed in what he was saying. He lived in an Ethiopia of his mind. And Ethiopia at that time really was very different.

Two months before I left Ethiopia for good, he told me this thing. I had known Mengistu for years, from when he was a good soldier. I knew his background. He was an ordinance officer, he hadn’t even been to the emperor’s military academy like I had, and he tells me, “Dawit, you know that by profession and training I am an economist.” I said to myself, “This guy has finally lost it. Either that, or he knows I can’t say anything.” I went to the minister of security, and I said, “Listen, I am worried: yesterday I was with Mengistu, and he told me he was an economist.” And he laughed and said, “Really? Yesterday, he told me he was a lawyer.”

It was clear to all of us in the government that the revolution was being misdirected. So the question became, “How on earth are we going to get out?” It was practically very difficult: in Europe or America, you can resign from office and live in peace. But in Ethiopia, the stark choice for disgraced politicians was to leave the country or be killed. And it wasn’t just you who would suffer: Mengistu would get your family. You had to get them out, too. What stops you from defecting is the terrible idea of being a refugee in another country. The other thing that keeps you going is the hope of ameliorating the tyranny. You think, “Can we go back to reality? Is there any way to change his mind?”

People always ask me, “Dawit, why did you stay so long?” But I have always thought that the hardest thing I ever did was to stay and work. Because I ignored Mengistu, the RRC saved millions of lives. A journalist once pleased me by writing that I tried to do good under difficult circumstances. I stayed and did my best. I’ll leave you to decide.

DEFECTION AND AFTERMATH

By late 1985, Dawit knew his days in the Ethiopian government were closing. He was summoned to a special meeting of the politburo. There, Shimelis Mazengia, the party’s chief ideologue, read out a list of Dawit’s crimes: “Comrades,” Shimelis said, “it is with great regret that I report that the ideology of the revolution has been compromised by the international organizations that the RRC has invited into the country. Comrade Dawit is either too naïve to see what the imperialists are doing, or he is collaborating with them.” In October, Mengistu phoned Dawit and told him, “You are out to create problems, Dawit, and I assure you it is going to stop.” It was the last time they spoke. On November 28, 1985, Dawit defected during a trip to New York.

I don’t really know why Mengistu didn’t have me killed. Perhaps because to the West I was the government of Ethiopia—its spokesman and most visible representative. It would have been difficult to get rid of me. So maybe Mengistu thought, “We’ll take care of Dawit later.”

In politics, we all make our internal calculations. We all know how much longer we have. I thought I knew with some accuracy what was happening. I had my ears. Under a dictator you spend a considerable amount of time watching and listening, because otherwise you don’t survive. So I knew that once the famine was over, Mengistu would take his own measures against me.

How did I defect? I was to go to a regular meeting of the United Nations General Assembly to ask for donations, but first I went to Brussels for a meeting of the European Union. While I was in Europe, I called my maid and she told me that some people had come and ransacked my house. I had left Ethiopia thinking, “One more time, after this I can go home one more time.” But when I spoke to my maid I knew my calculations were off. I called the minister of security and I asked him what he was up to, and when he said he didn’t know what I was talking about, I knew it was all over. When I got to New York, I disappeared.

It was very difficult to become a stateless person. It took a long time to get all my family out. But I wrote three letters to Mengistu that were later published as a book. In these letters, I went over all the problems in Ethiopia. I wrote about Eritrea, about the famine, about the revolution. It took me three or four months to say everything I wanted to say, and at the end I told him I wasn’t going home. Mengistu sent people to see me in America: he wanted to keep our disagreement a secret. He tried many things. He offered me an embassy in any country I wanted. He tried to blackmail me. But I applied for asylum, and became a refugee.

Was I debriefed by the American intelligence services? Many people ask about this. If senior people tell you they have not been debriefed, don’t believe them. Of course they have. If you are a defector seeking asylum, you are debriefed. But I had changed a lot over the years. I had become very practical. I knew that Marxism had failed. I told the Americans that I was totally opposed to Mengistu, and that I would do anything to expel his government. I would collaborate. I had some ideas, I said, about how we could work together. The Americans took care of me. I got a job at Princeton as a research fellow.

And I joined the opposition. I went into the anti-Mengistu movement with the same commitment that I went into the revolution. I organized something called the Ethiopian Free Soldier’s Movement. The Americans were funding the EPRDF [the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, that later formed the rump of the current Ethiopian government], so we allied ourselves with them. I went back to Eritrea, and for three years I worked with the opposition. I was involved with the failed coup of ’89, where so many officers were killed. I was the one on the outside organizing everything: I worked with the Americans, and kept the opposition united by guaranteeing that every faction would be represented in a transitional government.

I tried to enter Ethiopian politics one more time after Mengistu fled in 1991, but I couldn’t work with the present government. So I retired from active politics. I still have such an interest in my country: each of us has a mission in life, and my mission has been the politics of Ethiopia, but now I will influence my country and the next generation through my writing. I will never go home.

What will I write about? After Ethiopia, I sometimes worked for the United Nations. I was the head of the first United Nations team into Rwanda after the genocide in 1994. There were bodies everywhere. There were corpses in churches, there were corpses being used as roadblocks. It was a different kind of brutality from Ethiopia. I have been to every conflict in Africa during the last twenty years. Africa: Ethiopia, Somalia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Angola. There is a very disturbing question that needs to be asked: why is Africa the dark continent? No one knows the answer. Africans blame the West, or the colonial heritage, or apartheid, or even the international trade balance. But those answers don’t really answer the question. By now we should be sufficiently bored to examine ourselves and find out what is wrong with us. For fifty years Africans have had their own leaders. Anyone who achieves power in Africa is corrupted. Our leaders are not ignorant: they know better, they are people who have been educated in the West, who are familiar with the concepts of democracy, economic development, and law. The question is urgent. Everywhere in Africa, there are new crises and conflicts. I want to answer the question: why is Africa so awful?

Today, Dawit Giorgis is a research fellow at Cape Town University. He owns a small consultancy. Haile Mariam Mengistu lives in Zimbabwe, where he is protected by his friend President Robert Mugabe. Twelve million Ethiopians were close to starvation this winter—but the government of Prime Minister Meles Zenawi confessed its people were hungry, and international aid organizations donated 1.54 million metric tons of food, and $81 million in other assistance. There was no famine.