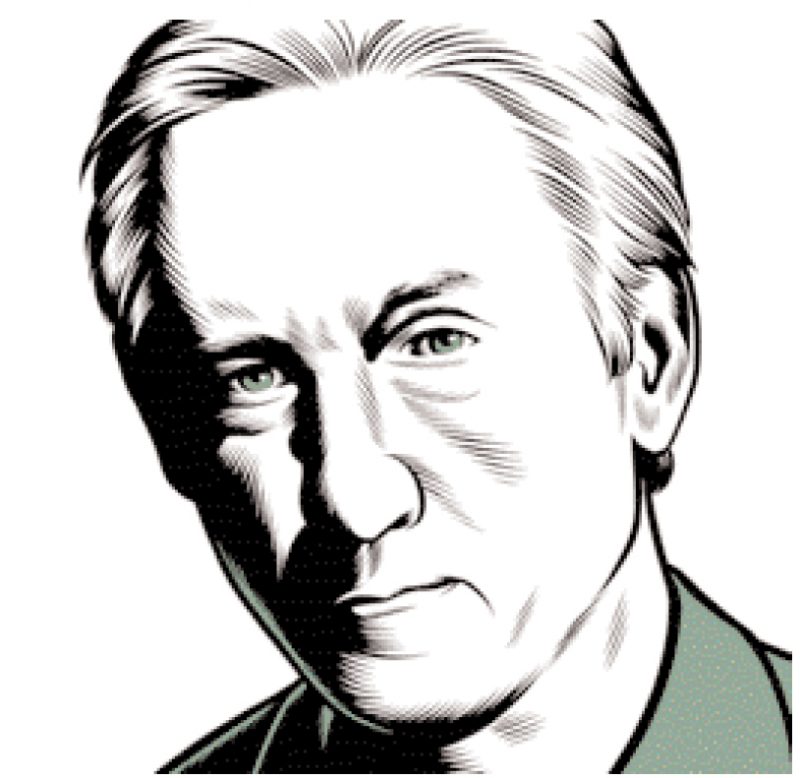

Ed Ruscha is an L.A. artist. In fact, he’s the L.A. artist, although the sixty-eight-year-old has always been resistant to easy labels (“I don’t write those kinds of histories for myself,” he says in a deep, muscular voice that betrays a hint of the Oklahoma lilt of his upbringing). His crucial series of photographic books, where he shot, among other things, twenty-six gasoline stations (remember this number) and every building on Hollywood Boulevard (and repeated this project in 2004) elides the usual photographic sentimentality because the structures are recorded with the cold, detached focus of impassive scientific observation. Ruscha, though, is primarily known for his paintings, which are no less unnerving in their chilly, deceptive straightforwardness. His word paintings—perhaps his most famous works—often turn single nouns, adjectives, or verbs into jarring, confrontational environments set in uneasy color surrounds. What is desire doing written in a milky liquid studded with blueberries (Desire, 1969)? Why is the word dimple, served up in clean, even red letters, suddenly violated by a C-clamp crushing down on the final e (Dimple, 1964)? Why is space written in zooming yellow 3-D block letters, crammed up at the top of the canvas, while a solitary pencil at the bottom is allowed so much legroom (Talk About Space, 1963)? On these canvases, the elementary words fight against all of their multiple meanings—in physical, emotive, connotative, and denotative form. Nearly half a century later, the paintings still hold their disturbing visual-linguistic currency. Ruscha’s lexicon still aggravates (I was gasping for contact swirls over an orange spiral), humors (brave men run in my family is printed against a ship at sea), and mystifies (baby jet letters hover over snowcapped mountains)—because we’re still speaking his language. Most recently, Ruscha has continued work on a series of bare industrial buildings set against swirling acrylic skylines. Perhaps the one thing that connects all of his work is an ongoing interest in the unreal spectacle of public space, which belongs simultaneously to everyone and to no one.

Last November Ruscha met with me on Manhattan’s Upper East Side in the lobby of the Carlyle Hotel, just before a series of paintings he’d created for the Venice Biennale were to make a second appearance at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Ruscha drank tea and talked more about Los Angeles than perhaps he wanted.

—Christopher Bollen

I. BABY JET

THE BELIEVER: It’s funny, interviewing you here in New York instead of Los Angeles. We’re sitting in a blue baroque tearoom off the lobby of the Carlyle Hotel, which is a bit like interviewing Woody Allen on the Sunset Strip. I actually have a photograph of you in my apartment walking down Sunset by a gas station, so let’s talk about roads in Los Angeles. You recently published a photography book, Then & Now, which built on your project in 1973 of photographing all of the blocks on Hollywood Boulevard from start to finish. You reshot both sides of the street in 2004 and ran them as horizontal bars right under the originals. That book is all about driving to me, looking out the window. How much does driving in L.A. influence you?

ED RUSCHA: I do drive a lot in L.A., and it really gives me all of my impressions of the city. They come right from driving. Sometimes I get into a groove where I’m listening to the radio—there is one particular number you can punch on the dial and it will give you two or three radio stations at once. It’s so comforting to listen to these overlapping effects. You might be hearing country-western music, stock reports, and a sporting event. Two or three programs overlapping each other can be used as a soundtrack for driving around L.A.

BLVR: What kind of car do you drive?

ER: I have a 1990 Lexus four-door sedan. It’s a boat. I got into the habit of big cars. And I always have my dog with me. He rides along. I don’t live and work in the same place. Once, I loved that kind of situation, but I don’t do it anymore. I live in a house in Trousdale, which is off Coldwater Canyon. My studio is in Venice. So I got a twelve-mile ride to my studio and it’s completely peaceful. I go about 8:30 in the morning and sometimes drive back at seven at night—if I don’t spend the night in my studio.

BLVR: That twelve-mile drive must be pretty important, given that so much of your work involves the impressions you take from the city.

ER: I also go to the desert a lot. I have a place out there, east of L.A., where the maps have no names. You can look at a map, and all these towns have names, and the highways have names. Where the names stop, that’s where my place is.

BLVR: What’s visually thrilling about Then & Now is the way it’s laid out, with the center of each page blank. The reader is actually driving down the center of the street—or down two Hollywood Boulevards simultaneously, one in 2004 and one in 1973. I’m not sure what’s more fascinating about the comparison—what’s changed on Hollywood Boulevard in thirty-one years or what’s managed to remain the same.

ER: There are big jumps, but it’s hard to say whether any progress has been made or not, and it’s not really addressing that question. It’s just presenting cold, concrete facts. There are lots of signs of progress and lots of signs of depression, so it’s up for argument.

BLVR: I think a lot of people outside of L.A. think of it as a new city. Isn’t it called “the City of the 21st Century”? But you’ve recorded a whole history of it that’s been lost, bulldozed, or utterly re-landscaped. Are those losses nostalgic to you in any way?

ER: You can immediately see the nostalgic aspects of it even if you’ve never been to Hollywood in your life. Europeans who haven’t seen America might say “gosh.” But I look at it more like an archeological study, where you may notice the Mann Chinese Theatre, but you also see the curbing and driveway entrances and light poles—how did they change over the years? So it’s not just the nostalgic aspect but the cold structural changes. I first came to L.A. back in the ’50s. I was riveted by Hollywood and Sunset. They were mythic streets. They were implanted in my brain all along. All I did was come back and photograph them. I shot other streets too, like the Pacific Coast Highway, which goes all the way through Malibu, and Melrose Avenue and Santa Monica Boulevard. At some point I may update those streets too.

BLVR: How did you shoot both sides of the street while driving?

ER: The first time, I had a little Japanese pickup truck, and I had a camera mounted sideways. I would be in the back with a motorized Nikon cruising along in this truck at six in the morning on Sundays, because there wouldn’t be any traffic then. There would be a driver in the front and someone changing the film. You could do that in 1973, but today the police would stop you. So this time I resorted to using a van with an interior camera. BLVR Why did you first move to Los Angeles? Aren’t all young artists required by law to go to New York?

ER: I guess as a kid I visited California. It was such an accelerated culture from where I was living. Growing up in Oklahoma, it was an extremely glamorous place. My impressions of New York—from the movies— were also glamorous, but it also seemed cold. It seemed too remote. The vegetation in L.A. always had an appeal to me—the palm trees and desertlike vegetation. All of those things combined to make me want to go there. I knew I had to move on from Oklahoma, and I wanted to go to art school. I thought I wanted to be a painter or a commercial artist, so that was my initial motivation.

BLVR: I’m not saying L.A. doesn’t have a decent art scene, but it certainly wasn’t the eye of the storm.

ER: That’s right. The art world in L.A. was minuscule. But there were key figures there that gave comfort to the thought of staying. New York was the art capital. We had these romantic pictures thrown at us from Abstract Expressionism—Pollock and de Kooning, all of them doing great things. It was always tempting to move to a place like that. But if you couldn’t afford it—and I couldn’t at the time… I’d put tail between legs and go back to California.

II. BRAVE MEN RUN IN MY FAMILY.

BLVR: There was a recent catalogue published on your early paintings that comes with commentaries on your work from various critics. For an artist who uses words—often just a single word—it’s fascinating how many different readings were posited. Do you enjoy this kind of linguistic battleground over your word paintings?

ER: Well, I never took offense to anyone’s misreading of a painting. I mean, man, it’s not my job to communicate with people. A picture is made in a solitary spot. Trying to reach people with a well-defined message is almost impossible, and unnecessary. So various interpretations of a single word are welcome. I might look at it forty different ways on forty different occasions. Take the word boss. I see it so many different ways each time I look at that picture. That’s the nature of art.

BLVR: Has the way in which you cull words and phrases changed over the years? I’ll never forget brave men run in my family. I always read that as “get as far away as possible.” You’ve said you take text from songs, conversations, television…

ER: Not so much television. Radio, particularly the car radio, and isolated sightings of some hot word I’d see in a book or a magazine. I was never that affected by television. I didn’t even have a TV as a kid. I didn’t get one until I was seventeen. Our family just didn’t have it, so the TV Age skipped me. I rarely think about it as a vehicle, whereas other forms of mass communication, I do—radio, movies, even dreams. Words come to me in dreams. If I do remember sentences, I have to write them down instantly or they’re forgotten five seconds after I’m out of bed. I’m going to forget them unless I absolutely sit down and write them. There is some wicked truth behind dreams. They are so out of your control. They’re involuntary. There’s got to be some protein to them, something important happening in dreams—especially the words that come out of them. It’s a diabolical time. The fact that you would dream about someone you never cared about in grade school who suddenly appears in your dream, why would that ever happen?

BLVR: They’re involuntary moving pictures. Have you ever considered making films?

ER: I made a couple of short films. They gave me a very quick look at how complicated making a movie really is. I like pictures. Here we have moving pictures—something accelerated beyond still pictures. There are a lot of people who have investigated film in all of its rawest ways. I think Warhol is one of the best filmmakers. Those movies he did—Sleep and Empire—were completely profound statements, and the movie industry laughed them off. The industry claims to be so into discovery, creativity, and all of that, but they dismissed those films as antics or stunts. When I made my films I was so busy writing checks and paying for equipment rentals that I had a headache by the time I was finished. It entails so much cooperation from people, it’s enough to make you weary. Everyone has their fantasies, though. I’d like to make a feature film some time.

BLVR: What kind of feature would you make?

ER: I don’t know. Maybe something about the desert.

BLVR: There are some great desert films, like Altman’s 3 Women.

ER: That was done in Desert Hot Springs. I haven’t seen that in many years but I remember liking it a lot.

BLVR: You must have a lot of Hollywood connections.

ER: None that I work. [Laughs] I’m committed to my studio, but it would be nice to make movies. It would require putting my life as a painter on hold. I’m not sure I’m ready to do that now, so maybe I don’t have that much to say after all.

III. ED RUSCHA SAYS GOODBYE TO COLLEGE JOYS

BLVR: I ran across a photograph of you from 1967 taken by Jerry McMillan. You’re under the covers in bed with two young women sleeping. It’s called Ed Ruscha Says Goodbye to College Joys. Did you come up with that title?

ER: Irving Blum came up with that. He’s a semiretired art dealer. He ran Ferus Gallery, which was a very progressive gallery in L.A. at the time. It started out as a coop and he had some very good artists. He gave Warhol his first one-man show of Campbell’s Soup Can paintings. He had a great Morandi show, and Lichtenstein, Kurt Schwitters, Jasper Johns—those were all international shows. But he had a stable of local artists too. That gallery was my introduction to the art world.

BLVR: You used that College Joys photograph as an announcement of your marriage in Artforum.

ER: Yeah.

BLVR: It ran like an advertisement. Did you have to pay an ad rate?

ER: No. What I did was I traded a work for that page to Charles Cowles, who owned the magazine at the time. He said, “OK, I’ll swap you a page for a work.” It was a little plaque with the word “California” on it.

BLVR: Last summer you were invited to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale and walked away with incredible reviews—even from dyspeptic critics like Benjamin Buchloh. Usually, the American artist who takes over that Jeffersonian pavilion in the Giardini gets critically thrashed. You showed two sets of paintings together—buildings painted more than ten years ago and the same ones updated today. Those weren’t real buildings, correct?

ER: No, they’re fictitious. I had a show in New York in 1992 at Tony Shafrazi Gallery. It was a two-man show with Dennis Hopper. He had big photographs and I had those paintings—I call them “blue-collar paintings.”

BLVR: Hopper is a good friend of yours, right?

ER: Yeah, he’s an old friend. He actually bought my first painting, a gasoline station, but eventually lost it in a divorce.

BLVR: It has to be out there somewhere still.

ER: That painting is now at Dartmouth College.

BLVR: You give a painting to Dennis Hopper, it gets loaded into a car with boxes and plants of a busted marriage, and ends up at Dartmouth. It’s comforting that those paintings don’t go missing forever.

ER: That’s the best thing that can happen to an artist— to have your work go to some secure location, like a museum or a university.

IV. PSYCHEDELIC INDIAN GURU NEW MEXICO FADE-OUT PHOTOREALISM

BLVR: The title of the show in Venice was “Course of Empire.” You’re there representing the United States in a time of little international support for this country’s foreign policy. Certainly, a title like that begs a political positioning of your paintings.

ER: If anyone wants to make that interpretation, that’s fine. It’s like going back to those word paintings. You can’t tell somebody how to think. I don’t come loaded with a message to impart. As far as using my art to make political statements, I always felt like there was a vacuum there. I’m a lefty. It’s not that I just keep my peace. But I can’t toot a horn through painting. I realize if I say “Course of Empire,” I might be toying with hot subjects. But the title actually comes from the Thomas Cole paintings. Somehow I felt there was a golden thread from his time to mine—his time being the 1830s and my time being the crass commercialism of today. [Laughs]

BLVR: Do you think you’ve become more sentimental as you’ve gotten older?

ER: It seems like with age you would build up a log pile of memories just by living that long, and you could constantly refresh yourself with these memories. But I don’t find myself getting nostalgic, particularly for the old days. It doesn’t help you in any way on the work you do today. Not for me, anyway. Some people abhor the idea of their past, so they naturally run from any traces of nostalgia. Just like Elvis Presley, who hated old things. He only liked new things.

BLVR: Did you keep any of your old paintings?

ER: I have a few, but most of my work is, regrettably, gone. I haven’t been exactly crafty or thrifty with my own work. I’ve sold it to advance my vocation. It’s a commodity, I suppose.

BLVR: Obviously, pop culture is a big influence in your work. Critics have often called you “the West Coast Warhol.” Does the idea of getting linked to a movement make you worry you’ll be frozen in historical ice?

ER: You could say I came out of a movement or a time of popular culture. If “pop” in Pop Art is short for popular culture, and that’s how I read it, then hell, I’m a pop artist. People always say, “oh, you must hate to be called a pop artist.” For a while people were calling me a conceptual artist because I did those books. I don’t write those kinds of histories for myself. Every day I wake up, I find there’s some new chore to take care of with my art.

BLVR: There’s a lot of violence in your work. You’ve used gunpowder as a medium. In your paintings you’ve set fire to art museums and gas stations. Is there any rage behind these works?

ER: I see violence or negativity of imagery as a tool in itself. It’s something I have to go through—it’s more the idea of fires than actual flames. I’m not lighting fires. It’s a way of attaching an additional meaning to the painting that would otherwise not have fire—if I can be so simple to say. And it’s fun to paint fire.

BLVR: So there isn’t an embedded desire to burn the Los Angeles County Museum?

ER: No. But if you want to see that as a political painting, you can—a revolt against an authority figure.

BLVR: What are you working on now?

ER: I’m twisted at the end and flipped upside down. I’m like a surfer who gets knocked off his board. You know, he’s twisted, rolling around, but he knows he’s in his element. I’m in the water with my own stuff, but I’m not on any particular roller-coaster track. I don’t know. I might make another book. But I’m always working on something. Every so often I’ll want to start working small or make some pastel drawings.

BLVR: I always love those artists who completely drop the kind of work they do and take up a different practice. Like, what if Ed Ruscha started drawing portraits?

ER: The idea of completely changing your work, there’s a hell of a lot of bravery in that. But some people have done it. There was this abstract artist, Harry Jackson—he was a friend of Pollock’s. One day he just quit and moved out west and started doing Frederic Remington–style bronzes of buckaroos on horses.

It all comes around. I did a drawing once of these words: psychedelic Indian guru New Mexico fade-out photorealism. I thought, hey, that encapsulates a certain kind of art that was being done in the ’70s. You go to an art museum in New Mexico, there are all these hidden Indians in the work.

V. BOSS

BLVR: You once said you thought of your paintings as book covers. You even painted the sides of the canvas to resemble book spines. Do you still see them that way?

ER: I completely see them that way. Maybe that’s my attraction to books—books as objects, anyway. I’m a complete romantic when it comes to that subject. The idea of designing a book cover and suddenly finding that the title of the book is actually the subject matter. If I paint a picture of the word boss, why can’t that also be the title? Maybe that’s all I’m doing: painting book covers.

BLVR: Do you collect books?

ER: Yes, I do. Not to the level of, say, Richard Prince, who’s an avid book collector.

BLVR: He’s building his own library in upstate New York that’s apparently fireproof. Do you have any valuable books in your collection?

ER: I have a Spanish book from the seventeenth century. It has a spongy soft velvet cover and Bible ribbons. I forgot where I got it. It might be worth something.

BLVR: You may not think of yourself as a romantic, but that series of mountains you painted some years ago with messages over them had a certain nature-as-inspiration feel.

ER: They’re ideas of mountains instead of mountains. I don’t paint like a naturalist would, or like Thomas Cole would. The image might have been sifted through decades of books and photographs. The concept of taking a canvas out into the wild, parking it there, and interpreting on the spot what I see to the left or to the right is out of my job description. Mine is more like interpreting through history or pathos—three times removed. Those mountains are not American. They’re based on Nepal, the Himalayas, the Alps, some from the United States, some from Alaska. They’re from all over, and it doesn’t matter. There’s no instruction or story that goes with it.

BLVR: I’m sure viewers in Europe might read those mountains as the Rockies.

ER: People in Europe may say I’m trying to discuss America, but I’m really not. Whatever comes out of my work is based on my exposure to the damned universe. Nonetheless, traveling in America, especially on its west side, gives me enormous inspiration. But it’s not the kind that translates directly into art.

BLVR: Have you ever driven across the country?

ER: Oh, yeah. And I’ve hitchhiked too.

BLVR: When did you hitchhike?

ER: I hitchhiked from L.A. to New York back in 1962. And in 1953 I hitchhiked from Oklahoma City to Miami and back. I loved the open road. You can’t hitchhike today. You can’t do it. It took me twenty-six rides from Oklahoma City to Miami and exactly twenty-six rides to get back.

BLVR: Exactly twenty-six? Each way?

ER: Yeah. I kept track of them. I’m always keeping records like that.

BLVR: I can’t imagine relying on hitches today. I just don’t think anyone would stop for you.

ER: No one would stop for you. Except the police.