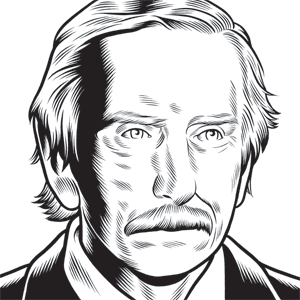

Having a conversation with Edward Albee about theater, even if you’re relatively well versed in the subject, is a challenge on the level of trying to play chess with a grandmaster. It’s not just that he’s more knowledgeable about his own work than any interviewer could ever hope to be, but you get the sense that he’s always one or two moves ahead of you. His mind works quickly, directing the exchange of information as though it’s a game and it’s the interviewer’s job to catch up and capture his interest long enough to elicit an answer—rather than a question—as a reply. There’s always a twinkle in his very blue eyes, suggesting this is all great sport for him. The two of you are engaging in a dialogue, but he’s writing most of the script.

Albee’s groundbreaking career in the theater spans fifty-five years. At eighty-five years old, he is the most decorated living American playwright and one of America’s most venerated writers. Among his many accolades are Pulitzer Prizes, Tony Awards (including one special award for lifetime achievement), Drama Desk Awards, the National Medal of Arts, and many more.

A “greatest hits” list of Albee’s work would undoubtedly leave out some of his most interesting plays. Those for which he’s best known—Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962), A Delicate Balance (1966), Seascape (1975), and Three Tall Women (1991)—are certainly deserving of praise for their acerbic humor, their wordplay, and their biting commentary on human relationships. But equally significant was Albee’s first play, The Zoo Story, a two-character one-act produced first in Berlin in 1959 and then off-Broadway in 1960. The confounding Tiny Alice (1964) is either a work of genius or a complete disaster, depending on which critic you’re reading, and The Goat, Or Who Is Sylvia? (2002) finds poignancy in, of all things, bestiality. For more than five decades, the defining traits of Albee’s plays have been their surprise and audacity.

I visited Albee in his Tribeca home in February, near the end of the run of the recent, Tony-winning Broadway revival of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the play that made Albee a household name and inspired the Oscar-winning film starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Since our talk, Albee reportedly has been completing a play called Laying an Egg. It will be his thirty-first play.

We were joined for this conversation by Jakob Holder, Albee’s assistant for the past twelve years, who is himself an internationally produced playwright. The three of us sat in Albee’s living room, among a rather imposing collection of African and pre-Columbian sculpture.

—Linda Leseman

I. COMMERCIALIZATION

THE BELIEVER: How do you see theater in New York now versus when you first came to prominence?

EDWARD ALBEE: I don’t have eight hours.

BLVR: Can you give me the abbreviated version?

EA: Yes, I will. How do I find it different? You asked about New York City. It’s a very long discussion about how the nature of theater has changed. I don’t know that we have time for it. I was thinking back; I was up to Lincoln Center last night, and they have photographs of their playwrights all over the place, and I was looking at the photographs: Lanford Wilson, all the people they’ve done. They were all together with me when we all started out in New York, and the theater experience was very different. So much has changed. What do you really want to know?

BLVR: Well, you were there, I wasn’t. I kind of want to know everything.

EA: I’ll try and see what the best way to talk about this is. The commercialization of off-Broadway and off-off-Broadway theater has gotten worse and worse over the years. Everything was quite spontaneous. “Wow! This is wonderful. Let’s just do it!” Nothing cost anything to do. It was very inexpensive. People worked for practically nothing and worked with great joy. Now you have to have three agents for every actor you want to stand by for a role on an off-Broadway production. It’s gotten so commercialized that the spontaneity has gone out of it almost completely. And you just did it because the work was there and everybody wanted to do it. We all got together and did it and had a wonderful time. And audiences showed up. And it was marvelous. Now you have to have so much planning. The commercialization is what’s happened, and it’s gotten really bad. It’s not as much fun as it used to be.

BLVR: Do you feel like what you did opened doors to—I’m not by any means implying that you’re responsible for any of that, but—

EA: I’m not responsible for the commercialization. The people who produce the plays are responsible for it.

BLVR: Right. But do you feel like the things you put on the stage, for instance Virginia Woolf—

EA: I’m talking about the off-Broadway stuff, before Virginia Woolf. I’m talking three years, four years before Virginia Woolf. Do you know about any of that?

BLVR: Of course.

EA: You do. You know about all that.

BLVR: Mm-hm.

EA: So we don’t have to talk about it, then.

BLVR: Like I said, you were there. I wasn’t.

EA: Well, I know, but Mel [Gussow] was there, and he wrote about it [in Edward Albee: A Singular Journey]. Did you read about it in Mel’s book?

BLVR: I read the whole book. I even have it on my computer if you want to refer to it.

EA: Really? The whole book?

BLVR: It’s on Amazon. You can get it as a digital download.

EA: Oh, really? Fascinating. So what were we talking about?

BLVR: People called Virginia Woolf—

EA: We’re not at Virginia Woolf yet. Why are you going ahead four years and skipping all the important stuff?

BLVR: What am I skipping?

EA: You’re skipping all the off-off-Broadway work that we all did together. That was the beginning of off-off-Broadway theater.

BLVR: Yes. This I know.

EA: So why have you moved to Broadway?

BLVR: I just thought I would take a little—

EA: You want to skip those four years?

II. “A LOT OF PEOPLE ARE CONFUSED BY ‘HELLO’”

BLVR: Let’s talk about two people sitting on a park bench in The Zoo Story. One of them ends up impaling himself on a knife. That’s kind of shocking.

EA: It is?

BLVR: Were you not shocked by it?

EA: Shocking in what context?

BLVR: Surprising.

EA: To whom?

BLVR: To the audience.

EA: Oh. Oh, yeah. Sure.

BLVR: I’m also wondering, why didn’t Peter leave?

EA: There would have been no fucking play.

BLVR: How do you keep two people talking?

EA: I don’t. They keep themselves talking.

BLVR: Do you feel like these characters are entities—

EA: They are three-dimensional, live people. They’re not characters.

BLVR: You don’t see them as any kind of aspect of yourself?

EA: No. I do not.

BLVR: Do you think that’s unrealistic?

EA: I think that’s foolishness on the part of the playwright to write about himself. People don’t know anything about themselves. They shouldn’t write about themselves.

BLVR: That strikes me as interesting, because your biography was written in such a way that it seemed to be saying—

EA: I didn’t write it.

BLVR: I know, but Mel Gussow said that your plays were your journals, in a way. Would you agree with that?

EA: Did I ever say that?

BLVR: You didn’t say that. Mel did.

EA: Well, ask him.

BLVR: He’s not around anymore.

EA: I know. I can’t answer for him. He said lots of things in that book that I don’t totally find valid.

BLVR: Really?

EA: ’Course. He tried too much connective tissue. All people who write about playwrights do that. I mean, I do not invent characters. There they are. That’s who they are. That’s their nature. They talk and they behave the way they want to behave. I don’t have a character behaving one way, then a point comes in the play where the person has to either stay or leave. If I had it plotted that the person leaves, then the person leaves. If that’s what the person wants to do. I let the person do what the person wants or has to do at the time of the event.

BLVR: Would you say you write character-driven plots?

EA: What else could they be driven by?

BLVR: Some playwrights seem to want the plot to supersede whatever the characters’ motivations are.

EA: Define plot.

BLVR: What happens in a play.

EA: “What happens in a play?” That’s the plot. OK. What does that have to do with the behavior of the characters?

BLVR: I guess that’s my question to you. Do you find that you have a plot in mind or that the characters’ motivations are driving the plot?

EA: I get some interesting people together, and I see what happens to them. Whether I have determined from before I start writing what is going to happen specifically? Not totally. What if that’s not the nature of the characters? I find out more about the characters. What if they want to behave differently? I give them their head to the extent that it fits into what I want to happen. It’s too complicated to simplify. What happens in a play is determined to a certain extent by what I thought might be interesting to have happen before I invented the characters, before they started taking over what happened, because they are three-dimensional individuals, and I cannot tell them what to do. Once I give them their identity and their nature, they start writing the play.

BLVR: Do they leave mysteries to you? Do you know everything there is to know about all of your plays?

EA: What do you mean? You want to talk about all the plays at once?

BLVR: You don’t have to.

EA: I keep asking questions.

BLVR: I noticed that.

EA: I’m trying to find out what we’re talking about.

BLVR: So, the characters take over, as you’re writing it.

EA: They have to. How else can they be three-dimensional people?

BLVR: And when you come to the end of it, do you find that there are questions left in the play that you, Edward Albee, don’t know the answers to?

EA: Give me an example of a question I wouldn’t know the answer to.

BLVR: Why did Peter not leave?

EA: Because he’s been sitting there talking with Jerry for a long time. He’s become mesmerized by the environment, by the situation, by everything that’s going on. That’s why he doesn’t leave. If I as a playwright thought, With logic, he would leave now; he wouldn’t stick around, then I’d have him leave. I’d write another play instead. I don’t remember ever saying, “No, I have to keep him around for certain plot ideas.” I don’t think in those terms. These turn into real people with their own minds and their own answers and their own questions.

BLVR: So back to my question: do you have any questions about your own plays that you feel remain unanswered?

EA: Well, you go into rehearsal, when directors and actors start asking all sorts of unnecessary questions, because they don’t understand half of it—the nature of the characters. Almost all of those answers, if the play is well constructed, are answered during rehearsal. You solve all those problems. Sometimes it’s because the actor doesn’t understand the character. Then you fire the actor and get another one who will understand what’s going on. There may be lots of questions that anybody—an actor or a director or anybody—can ask about a character in a play of mine that are not answered in the play, but if it’s a question that I don’t think is relevant, I don’t bother about it. There’s no reason to ask it.

BLVR: Tiny Alice, for instance. It seemed like a lot of people were confused by it.

EA: A lot of people are confused by “hello.” A lot of people are confused by a lot of things they shouldn’t be confused by.

BLVR: You don’t find it confusing?

EA: No. If I found it confusing, I would have de-confused it. I found it sometimes a little obscure, a little difficult, but shouldn’t something go on in a play besides simple, straightforward statements?

BLVR: I like that.

EA: Me too. A lot of people don’t. But that’s their problem, not mine.

III. TO BE A PLAYWRIGHT THEN

BLVR: Do you feel like today we hold playwrights in high enough regard? I continued to think, as I was reading your biography, that you were—

EA: Don’t pay too much attention to that. That’s things that happened. Those are facts.

BLVR: Was it a fact that you were sort of treated like a celebrity? As a playwright, you were kind of a celebrity. Is that fair to say?

EA: Isn’t that true of all playwrights who have any reputation?

BLVR: Well, no.

EA: How was I a celebrity any more than any other playwright? Have you read all the biographies of all the playwrights who came along when I did?

BLVR: No.

EA: All right. I didn’t know that I was a celebrity.

BLVR: You didn’t.

EA: No. I thought that I was getting some of the credit that I deserved for some things and some of the blame for things I didn’t deserve. And maybe some of the blame for things I did deserve. Maybe I should be blamed for being obscure, as I am in some plays. Blamed for being obscure? That’s one of the things. Sometimes you write diatonic music. Sometimes you write dodecaphonic music.

JAKOB HOLDER: But there is something that your producers, Richard Barr and Clinton Wilder, did specifically in order to create a sense of playwright-as-focus that hadn’t existed before.

EA: Well, they may have tried to make me a little bit more a star of my productions. But I never called them up and said, “This is Edward. Make me a star of my plays.” I never did that. If there was something about the plays that led to people concentrating more on the playwright, that’s because the playwright writes well. Writes interesting stuff.

BLVR: I can’t think of an analogous playwright that would be a household name who’s writing today. Can you?

EA: Well, I’ve been writing for a very long time.

BLVR: Even at the time that you hadn’t been writing for a very long time, people knew who you were.

EA: Oh, come on, there were lots of us at the very beginning there. There was Jack Gelber. Remember Jack? Ever seen a play of his?

BLVR: No.

EA: You should read everybody’s plays from that period to understand what was going on in that period. You have to know Jack Gelber’s work. You have to know Arthur Kopit’s work. You have to know Lanford Wilson’s work. You have to know the work of all of those people to know what it was like. That’s the only way you can tell what it was like. We were all writing of a certain intensity, and you have to know the work of all of us, not just me, to know what it was like to be a playwright then. You won’t know unless you know all the work of all of us and the environment that we all worked in. So, read ’em all! You’ll know an awful lot more about what it was like to be a playwright then. Then you won’t say things like I was the only one who was a star.

BLVR: I think about today, about literary “stars” of today—

EA: What does “star” have to do with anything?

BLVR: I think it’s a cultural phenomenon, and I find it interesting that a playwright was elevated to that. Nowadays, I can’t think of a single playwright… I mean, somebody might know who wrote Harry Potter, but they wouldn’t know who wrote a play on Broadway.

EA: Most plays on Broadway are written by committees, anyway. It doesn’t matter. You can’t think of any well-known playwrights?

BLVR: I can think of some, but I don’t think that somebody—

EA: [To JH] Who are the well-known playwrights today?

JH: There aren’t any. I think that the question really is, when you talk about the nature of a household, which household would have the name “Edward Albee” passing around the dinner table in 2013? Do people talk about the theater the way they did in 1962?

BLVR: No.

JH: So the fact that those of us who are trying as hard as those guys did then will likely never get the recognition they did is probably partially due to the fact that audiences are not led to consider theater as essential an art form as they used to.

BLVR: Whose fault do you think that is?

JH: I’m only thirty-four. I also wasn’t around at the time that they were, but the little that I’ve lived and paid attention, I would say it’s as much the audiences’ fault as the producers’ fault, all kind of giving in to each other’s sense of where the money should go.

EA: All of a sudden there was a generation of young, serious, talented American playwrights. And there hadn’t been for a long period of time. And we were all new. It was all fresh. And the audience seemed interested and willing to participate. And so we all came along. We all had a wonderful time. It was marvelous. Some faded. Some kept on. That’s the way it is with everything.

BLVR: In popular music there’s always a new, fresh thing coming up. And the rest of the world seems to know about it.

EA: Most all of that is an attempt at commerce. You’re confusing art and commerce.

BLVR: But your plays were both. More art than commerce…

EA: But most people who become the most popular are more concerned with commerce than they are with art.

BLVR: What’s the solution?

EA: The solution is to let the people do what they want to do. And to pay more attention to the good ones and less attention to the bad ones. Why are Broadway theaters filled with bad theater? Because it’s being sold to people as something they should participate in, not because it’s going to change their lives or because it’s going to change the nature of theater. They’re given other reasons to see it. It has movie stars in it. It’s a laugh riot.

JH: You know, the current production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? doesn’t have a single what they call “bankable star” in it.

BLVR: Tracy Letts is kind of a big deal.

JH: Theatrically, but he’s not a TV star, not a movie star. If you stuck Bryan Cranston from Breaking Bad into Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, it would probably run three times as long as this production will run, because people are not seeing it to see Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? They’re seeing it to see Walter White from Breaking Bad strutting around onstage. Which is the only way a new play gets done on Broadway. You lose the star; the play doesn’t get done.

EA: It all has to do with commerce, not with art.

BLVR: Where do you go to find the art now?

EA: Off-Broadway and off-off-Broadway. Occasionally something on Broadway turns up. A bad production of a Beckett play will turn up on Broadway every now and again.

IV. CRITICAL STUPIDITY IS NOT A LAW

BLVR: The process a playwright has to go through to get their work produced now is so different from what it was like when you first started out.

EA: Has to go through?

BLVR: For instance, you ship your plays off to the literary manager of the theater, and you hope that some intern is going to read them someday.

EA: I don’t do that.

BLVR: Not you, personally.

JH: I do.

BLVR: It’s kind of sad, you know?

EA: Why does that have to happen? Does it have to happen?

BLVR: It seems like it. Besides being Edward Albee, how else does a playwright get produced nowadays?

EA: How else? You mean, there’s no way to get a play on rather than to go through that process? If the most important playwright of the last twenty years of the twentieth century suddenly came along, I don’t know that they’d have to spend ten years waiting for their first production. I think somebody might be bright enough to figure out this is about the best play of the last twenty years and get it on. Some critic might be bright enough to figure that out. It’s not a law. Critical stupidity is not a law.

BLVR: You’d hope not. Maybe I don’t have enough faith in—

EA: It probably is a little more difficult—and [Jakob], you can answer this question more than anybody else can—it is probably a little bit more difficult now to get your way through the maze of interruption, because there’s so much more commercialization in the theater. No play by Samuel Beckett has ever run as long in any production anywhere as a junk play. Now, why have people been trained to want junk plays? They didn’t always. It’s because junk has been pushed to sell. And you have audiences and, to a large extent, critics who want less from theater than it is possible for it to give. If everybody’s encouraged to want less, you’ll end up with less.

BLVR: That’s definitely the case in the more commercial space.

EA: Do you know how much it cost [in 1960] to produce a play off-off-Broadway?

BLVR: No.

EA: You could get one done—I don’t know how much The Zoo Story cost when we put it on in New York for the first time. You can look it up in Mel’s book, probably. But very, very little. I think it cost something like eleven hundred dollars to produce. Now you have to use at least sixty thousand. The prices of things have gone up. The costs of things have gone up. Partially because of inflation, partially because of the greed of the people who are doing things. They won’t do it unless they’re overpaid. And there is some resistance to the low-price ticket.

BLVR: Why?

EA: Well, it can’t be any good if you’re not charging us a lot to see it.

BLVR: That’s absurd.

EA: Of course it’s absurd. I thought we were talking about American theater.

V. IT HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH THEATER

BLVR: What are your thoughts on the MFA degree institution? It seems like now playwrights have to go through this sort of vetting process. If you’ve been anointed with the MFA—

EA: What is the MFA?

JH: Master of Fine Arts degree.

EA: I wasn’t aware of that.

BLVR: Really?

EA: I didn’t know that was a law now.

BLVR: Well, not a law, but—

EA: Is there somewhere that says you must have an MFA degree to get anywhere in the theater?

BLVR: Well, no, obviously if you’re—

EA: What is your question based on?

BLVR: My question is based on a trend I’ve observed that many—

EA: Most trends exist because they’re permitted to exist and have not been slaughtered.

BLVR: That’s well said.

EA: I know. I thought it was when I said it.

JH: The truth is that we, as young playwrights, obviously don’t operate in a vacuum, but I don’t have an MFA, and I refused to get one. That doesn’t mean that there isn’t—

EA: I got thrown out of college.

JH: I’m sure Samuel Beckett didn’t have an MFA. But nowadays, you’re right. The trend is that it’s almost as though there were a tunnel from MFA programs to literary or artistic directors’ offices and that anybody who doesn’t pass through that tunnel has at least a very difficult time, if not an impossible time, getting recognition from theaters.

Now, if all of us as young playwrights decided to, in a sense, band together as a community and say, “I refuse to pay a hundred thousand dollars to be given a piece of paper that says I’m allowed to be a produced playwright now,” perhaps the theaters would do plays by people without MFAs. But there’s so much money to be made from MFAs that there’s almost no reason for that system not to perpetuate.

BLVR: There’s also the gleam of having a position at a university. There’s the safety net if you have had that advanced education, but it’s kind of cushy, in a way.

EA: It’s kind of what?

BLVR: Cushy. You know, cushion-y.

JH: You mean that playwrights can then teach and make money?

BLVR: Yeah. It’s a self-perpetuating system.

JH: [To EA] You generally can’t teach in a theater department unless you have an MFA.

EA: Really? I managed. Well, I’m aware of all this nonsense. But it has nothing to do with theater. It has to do with the forces of evil that are standing against theater proceeding the way it should.

BLVR: Besides producers and commerce, what other forces of evil would there be?

EA: Lazy audiences. Audiences that are encouraged by critics and by what’s available to expect and want less each year. There’s less good theater being done all the time—anywhere anybody’s going to get the chance to experience it—because the very good stuff is not going to be as popular. But is the very best ever, in any art—any serious art—available and accessible to the ignorant, to the people without an education in the arts? No. Of course not. And the assumption that the arts have a responsibility to be more accessible than they need to be to accomplish their purposes? No! But if you want a commercial success—it’s the confusion of commerce with art. A successful play is not considered to be the best written. It is the one that sells the most tickets. Those standards are destructive.

BLVR: Should they all be free?

EA: Everybody wants to go see the big hit. Not because it’s any good. Because it’s the big hit and everybody wants to be able to talk about the big hit. Why?

BLVR: To be “in” on something.

EA: To be in on what? I don’t know what any of that means.

BLVR: It doesn’t mean anything to me, but I think that some people want to be able to say, “Oh, I saw this big show.”

JH: It’s the having-your-ticket-ripped phenomenon. One time a year, you pay $150—

EA: Or more.

JH: Or more. In order to see it-doesn’t-matter-what; in order to say to your friends, “I went out and bought a T-shirt at this New York City theater.” They had their ticket ripped, and they did their cultural duty for a year.

EA: What does that have to do with theater as an art form? There is not much concern anymore with theater as an art form. And that is the fault of the people who put up with it. If that’s what they want, I suppose people should get what they want. This is a democracy.

VI. “I’VE GOT A GOAT HEREIN THIS PLAY”

BLVR: What do you think would be the most shocking thing that someone could put in a play now?

EA: The most shocking thing? Define shocking.

BLVR: Shocking in that it generates a strong critical response.

EA: Critical response by critics?

BLVR: And also by the people who go to see it. Where it creates polarization and ambivalence.

EA: That’s an interesting question to answer. You mean it has to be both favorable and unfavorable?

BLVR: Like the responses to your plays. They were very much that way. So what do you think now would be the most polarizing thing a person could put in the theater?

EA: Probably to write an absolutely wonderful play in which there was nothing shocking. Nothing surprising at all. Because most shocks in plays are put there for that purpose, and that is not natural writing. That is putting something in intentionally to shock an audience out of participating in a play.

BLVR: Do you know the first play I ever saw on Broadway? It was The Goat, Or Who Is Sylvia?

EA: For heaven’s sake. That’s a good start.

BLVR: The relationship between the male lead and the goat was rather shocking.

EA: Wasn’t shocking to him. It was shocking to whom?

BLVR: It was shocking to some of the people who saw the play.

EA: Yeah. I thought some people would be offended and bothered by it, yes.

BLVR: Was that intentional? Did you put it in there to shock people?

EA: Did I put it in there to shock? No. I put it in there because that’s what was happening. Don’t accuse me of doing anything to shock.

BLVR: OK.

EA: That’s an insult.

BLVR: It was a question.

EA: No, it’s an insult. I would never do it. Some playwrights would. I wouldn’t. I mean, some people are quite capable of writing a play in which there’s a goat in the play and nothing happens. No relationship occurs between the goat and any of the humans. In my play, something happened between the goat and one of the humans. That wasn’t done to shock people. It was done because that’s what happened. I didn’t suddenly decide, Oh! I’ve got a goat here in this play. Maybe I can have them fucking!

JH: Imagine if they were fucking onstage. That would be you putting something intentionally onstage to shock. In that respect, you were withholding.

BLVR: What’s left to the imagination can be even more grotesque than what would have happened in reality.

EA: That’s on the assumption that in a civilized society people don’t fuck goats.

VII. A HUNDRED YEARS FROM NOW

BLVR: Are you happy with the life you’ve had—the life that’s behind you?

EA: Well, I wish I remembered more. My mind is going. Not very quickly, but I’m forgetting more things all the time.

BLVR: Really?

EA: Yeah, of course.

BLVR: Like what?

EA: Um, what I did ten minutes ago.

BLVR: Really?

EA: Wait till you get to be my age. Just wait.

BLVR: How do you want people to remember you?

EA: I’d love if they’d wait until I die.

BLVR: I mean a hundred years from now.

EA: Oh, a hundred years from now. Oh, the fact that they do—that would be enough.

BLVR: You know it’s going to happen.

EA: That I’m going to die, or that they’re going to remember me a hundred years from now?

BLVR: Both of those things.

EA: That doesn’t necessarily mean that when I die they’ll remember me a hundred years after I die.

BLVR: I think you probably will be remembered.

EA: It’d be nice. Although I’m not going to care much.

BLVR: Do you care now whether you are going to be remembered a hundred years from now?

EA: My ego does.

BLVR: Yeah?

EA: Yes. Do I? No, of course not. Because I know I’m not going to be around to experience it.

BLVR: What does that feel like?

EA: Not being around to experience it? I don’t know yet.

BLVR: No, knowing that things you’ve said, things you’ve done, are going to be talked about when you’re no longer around. What does that feel like?

EA: Well, that happens all the time. Every time I go out.

BLVR: You know what I mean.

EA: I don’t think about myself in the third person. He, I, he. I don’t do it. I’m suddenly startled sometimes: “Oh, we were sitting around, talking about you the other night…” Why the fuck were you doing that? Then I find out there was something interesting they might have been talking about, either right or wrong. If it was wrong, I correct it. If it was right, I’m delighted. I don’t go outside and think, OK, here’s Edward Albee going outside. I don’t do that. It’s me going outside.

JH: What’s wonderful is that he’s blissfully unaware of what most of what the internet is, and one time I tried to break that barrier and say, “Take a look at this. Somebody’s described you walking down the street and entering this building and carrying a pear. Isn’t that strange that you did something so basic and simple and human, and someone thought enough of it to want to put it up for millions of people to read?”

EA: Why did anybody find it strange that I was doing something like walking around with a pear.