The first paintings were domestic in subject and radical in nature. These were lucid suburban narratives bathed in pellucid oils of sunlight and frozen on bodies, often naked with legs splayed, caught languishing in master bedrooms or sunning restlessly on crowded beaches. In Sleepwalker (1979), a post-pubescent boy masturbates in a backyard wading pool over his own shadow as two empty lawnchairs watch from the sidelines. In Bad Boy (1981), an older woman, lying nude on a bed, picks at her foot while a young boy secretly slips his hand into her open purse. Eric Fischl’s paintings rarely preach, but their frank, coolly aloof treatments usually fixate on American family or marriage life at its most ordinary, most stripped, and most dysfunctional. Their entrance on the scene came during the reign of minimalism and conceptual art, when the painted human figure was about as acceptable as speaking Russian or joining the U.S. Army. It was Fischl, along with artists such as Julian Schnabel, Ross Bleckner, and David Salle, who literally resurrected the human body and returned it—kicking, fucking, sleeping, and mowing the lawn—to the galleries and collections of the early 1980s.

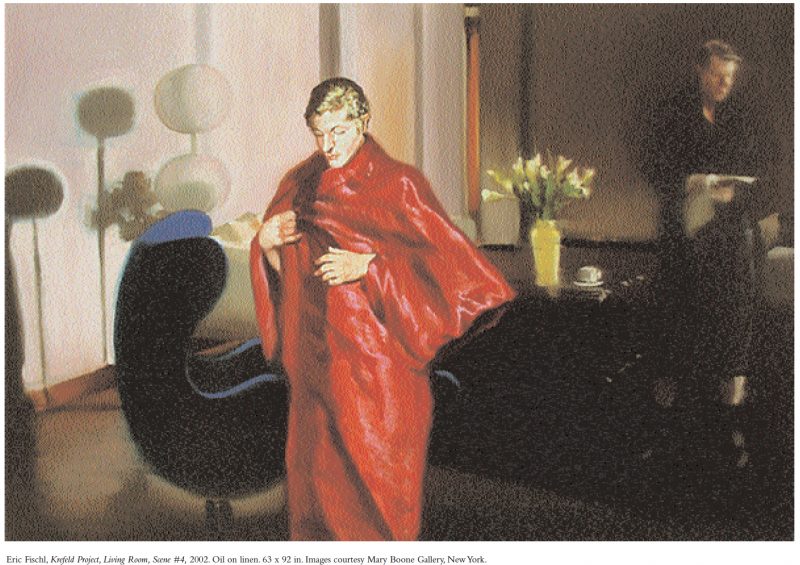

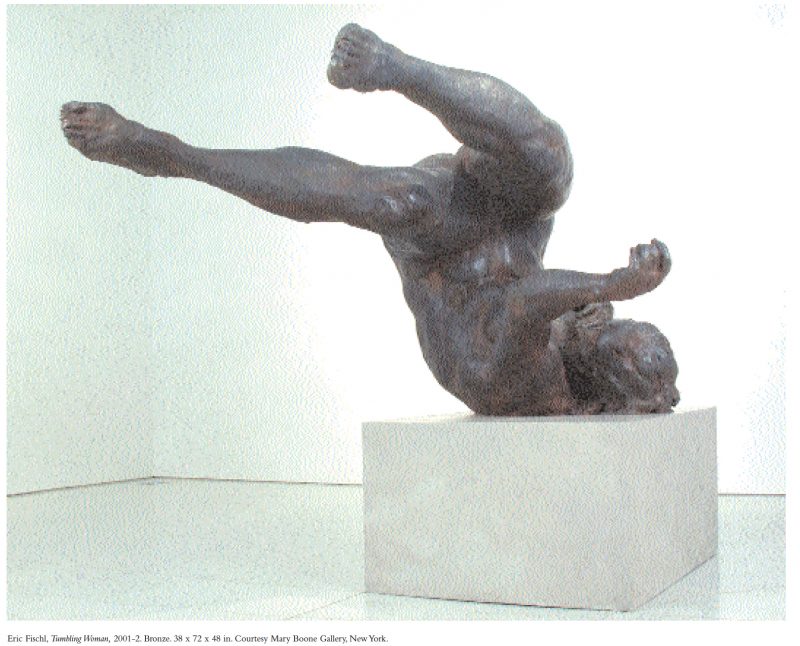

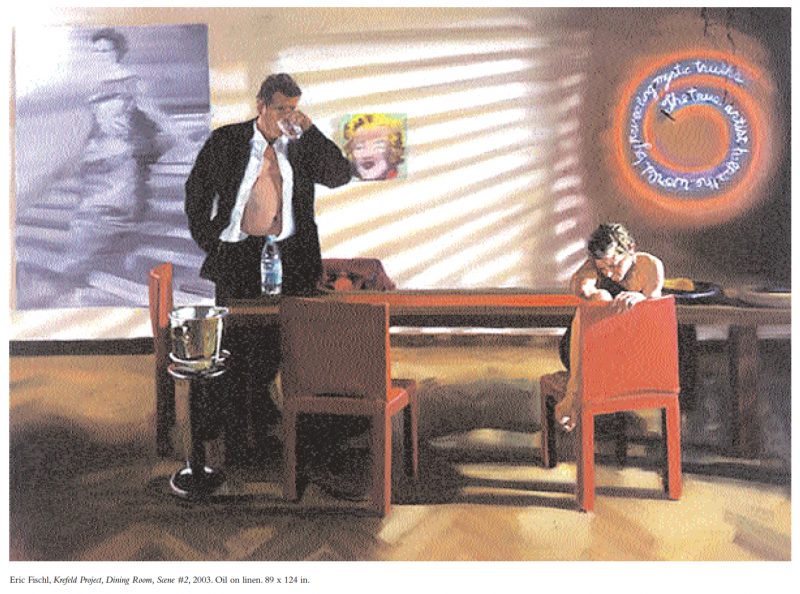

Don’t miscast Eric Fischl in the role of bad boy, however: he was never really bad, and he was never just a boy caught between an open purse and an open body. Fischl’s work has progressed through the years in incredibly sinister and seductive ways—roaming from India to Italy, and from pivoting corporal watercolor forms across white paper to memorializing friends and famous acquaintances in head-to-toe portraiture. In 2002, controversy surrounded his sculpture of a woman falling in space (Tumbling Woman, 2002), inspired in part by those victims of the World Trade Center attack who jumped from the windows before the buildings fell. The memorial sculpture, placed at Manhattan’s Rockefeller Center, drew public outrage and the usual conservative mill of shock-art criticism. Fischl meant to express grief, not to give it, but like most of his works, it brilliantly exposes the runny gray area between art-world and popular values, acceptability and expression. Currently, this master of the figure is painting domestic scenarios modeled on two actors whom he routinely photographs by following them around the house. Any trace of scandal appears to have died down lately, but his dark vision of human interaction is still alive and well.

—Christopher Bollen

I. “UNTIL WE EMBRACED IT, AND SO MANY MEMBERS OF MY GENERATION DID, SUBURBIA WAS NOT CONSIDERED A LEGITIMATE GENRE.”

THE BELIEVER: It seems like figure painting isn’t just back, it’s pretty much ubiquitous—especially with younger artists. I’d think you must be something of a role model for this aspiring generation.

ERIC FISCHL: I think there’s been a paradigm shift. Not an uninteresting one, but one that, on a fundamental level, excludes me. My generation was the last generation to embrace anxiety as content for art. That manifested itself in formal terms—attitudes about gesture, edges, a certain kind of violence to the canvas, a certain disrespect and angst.

BLVR: You feel like today’s art isn’t angsty?

EF: I think they have decided that there isn’t a place for it in art. So it’s not that they are less anxious as a people, they just don’t see it as a subject matter. Today, there is a playfulness, an innocence. One of the generational differences is the sources. Today’s figurative images are inspired by kitsch, cartoons, anime.

BLVR: You once said you were inspired by film and television. How is that any different?

EF: The kinds of film and TV were different. For me there was more of a realism to it. Like Hitchcock— film-noir type things. Now there is a lot of attachment to video games and that kind of mediated world.

BLVR: You mention your generation, and really, in dealing with your work, it’s hard not to talk about it. You were and are so often linked with “Eighties Artists.” Does that term dog you today?

EF: I have mixed feelings about it, because when you say that it seems like a fixed thing. I look back on the late seventies and early eighties as one of the most exciting times. It was the prime of my life in one sense. It was unlike most historical moments in art, because it wasn’t just the next generation coming along to displace the reigning group. No, there was an entire shift taking place. There was the influence of the feminist critique, which affected what we considered subject matter and style. There was a reassertion of European artists who had been closed out by a New York chauvinism. All of a sudden we were being exposed to work from Germany, Italy, everywhere. There were also racial issues being addressed. There was so much stuff impinging on the moment that it was incredibly exciting and confusing and exhilarating. The gateway in New York art was just bursting with multigenerational, multicultural needs. It just blew through, and it was great.

BLVR: There was all of this multiculturalism, yet your work focused on white, suburban middle-class families largely in moments of leisure.

EF: I was dealing with an insecure area artistically. The style and manner and traditionalism of my work—my work was never academic, although it was often accused of being such; I wasn’t good enough to be academic in terms of technique to be accused of that—they were all incredibly vulnerable areas. So what I did to protect myself was to focus on something I knew, so nobody could take that away. What I knew was a certain suburban upper-middle-class life. I knew dysfunction in the family structure. So I drew on those. Are any of the scenes I painted autobiographical? No, they’re fictions. They are compilations and conflations.

BLVR: Sleepwalker and Bad Boy quickly became the defining paintings of an era when they were first shown. But entering the New York art world wasn’t all acclaim for you. Certainly, there was a resistance to your style.

EF: Until we embraced it, and so many members of my generation did, suburbia was not considered a legitimate genre. You had urban. You had bucolic. But the suburbs were a no-man’s-land of no content. What turned out, of course, was that most members of my generation came from the suburbs, so we had a different relationship to it and a familiarity with it. Of course, the suburbs began with my generation. We could be the voice for it. Now it is commonplace, but it wasn’t at the time. If you wanted to make art about urban life, great. Or the honest farmer and the pastoral landscape—that had a legitimate historical genre. Whereas someone at a shopping mall or watching TV…

BLVR: Eighties art has had a renaissance lately, specifically in terms of the political, anti-Reagan, agenda-driven content of that decade—groups like ACT UP and the Guerrilla Girls. I think there is a tendency to see eighties art in two camps: the social-justice fringe camp and then those artists—more traditional, often young white male painters—who were making names and fortunes in the New York gallery world. This is a crude line to draw—aesthetes vs. activists—but is it an accurate one? Was there such a feeling at the time?

EF: I think that we, and again I’m saying the generation as we, had a profound degree of self-consciousness. The self-consciousness came from a feeling that everything was a cliché, that everything had such a strong predecessor to it—that basically you were in pantomime. So political art seemed like a stylistic choice as opposed to a political choice, the same way that painting sexual imagery was a stylistic attitude instead of something about its content. A lot of discussion in my generation, through the art, was about whether you could legitimately make work that had an initial impact, as opposed to a self-conscious one. You had artists making art about whether painting was dead or not. Artists were making dead paintings to show you that painting was dead. And there were artists trying to make live paintings, fearful that maybe painting really was dead after all. Cindy Sherman’s early work imitated film stills. Robert Longo was imitating advertising. You had many artists working in a self-conscious way. The success of it was something that became a critique of it. But I never equated the two. The success was being in the right moment at the right time and filling up what was clearly a profound need in the art community—for museums, galleries, and collectors—for something that felt new and vital and exciting.

II. “SO MUCH OF WHAT I DO IS ABOUT RECREATING A KIND OF MEANING BASED ON BODY LANGUAGE.”

BLVR: And then you suddenly switched out of suburbia and went to India.

EF: India was incredible. It’s the furthest away from familiarity with what I know that I’ve ever been. And I’ve been to other places. I’ve been illiterate but still didn’t feel as far away from what I understood. I couldn’t read India. I couldn’t read the body language. I didn’t know the signals. I didn’t know what was an OK situation and what was a dangerous one. It was also so exotically beautiful, an assault on every sense. The smells went from the most exquisite to the most disgusting. Visually, it was so rich and also so shocking and desperate. I didn’t go there with the intention to do anything. We were invited. My wife wanted to go. I tagged along with a lot of trepidation. When I came back it was all I could do to paint it.

BLVR: It must have been interesting as a figure painter to go to a place where you couldn’t read the body language.

EF: So much of what I do is about recreating a kind of meaning based on body language, on gestures, without attaching specific meanings to what the body language is. It’s about how you read something before you know what’s actually happening. Here was the place where my readings were askew. When the work was shown, I was accused of a kind of colonialism, which I thought was very funny. The experience of the work for anyone who stands in front of it is that you feel outside. What are you doing here? That’s not colonial as far as I understand it. There was also enough of a hangover from critical expectations of sixties and seventies art, where artists got their styles and had to do them the rest of their lives the same way. Critics saw these as some huge shift in my work. To me, I was looking first at suburbia and then at India with the same eyes.

BLVR: More recently, your eyes have turned to much more specific characters. You’ve been doing a series of portraits—faces that stare out at the viewer with a sort of intimate chill. I’m thinking particularly of the portrait you did of Joan Didion and her late husband, John Gregory Dunne [ Joan and John, (2001–2002)]. How do you choose the people you paint?

EF: For the most part, I started to do portraits because I know I have this amazing life beyond my own expectations. I’ve been in contact with and surrounded by extraordinary people. It just seemed to me that one of the cultural jobs of the painter is to remember those people and memorialize them. Painting portraits of people is different than taking photographs of them. Paintings monumentalize people in a way that photograph portraits can’t. So that’s why I started. I asked people I knew and have been influenced by. Joan is one of those people whom I have read continuously since college. Her essays are so perceptive. And I loved the couples thing. I’m married to another artist [painter April Gornik].The idea of creative couples is an interesting and complicated relationship.

III. “FREEFALL WAS A METAPHOR FOR THE COUNTRY.”

BLVR: And lately you did a public memorial. It’s timely to bring up your 2002 sculpture Tumbling

Woman—just recently in the New York Times there was an article on the victims who jumped from the World Trade Center. The article reported that not one person who jumped from the towers—and they think the number is as high as two hundred—has ever been officially identified. They mentioned your sculpture when discussing the idea that the population can’t for some psychological reason handle this fact—of victims jumping or falling to their deaths. It’s a factual blackout, and perhaps this explains the outrage over your sculpture at Rockefeller Center.

EF: In the days after 9/11, I was absolutely convinced that artists had to come to the occasion. This was such a huge event that artists were needed to make sense of it. We had to address the tragedy, the complexity, the human experience of it. I had that in my mind for six months or so before I made the piece. One thing that stuck so deeply in my imagination was trying to imagine how horrible an experience would have to be that you would choose one form of death over another— the image of people leaping, falling. It started to make sense that freefall was a metaphor for the country.

America was now in freefall. I didn’t call it Falling Woman. I called it Tumbling Woman, because when you look at it, it looks like it’s moving in a lateral way, like sagebrush. It feels like it will keep rolling along. I was alluding to the falling people, but I was trying to make it more than that. The strong reaction against the piece was in part because there were so few images of the people who died. The buildings pulverized the death, and the images that did exist were censored by the media in fear.

BLVR: I think that’s why those few and rarely seen images of people at the broken windows are so strong. You want to see the human beings in the buildings. In some compulsive way, you want to know that the deaths were real.

EF: The discussions and arguments were all about the buildings—replacing the buildings, what kind of memorial, etc. Even George W. Bush, when he visited the site, promised we’d get revenge on the people who “brought these buildings down.” Those were his words. Buildings, as though there weren’t three thousand people inside of those buildings. Who gives a shit about the buildings? Think about the kind of censorship going on now with the images of the war and how we are not seeing the carnage or the human devastation. We see cars being blown up and people standing around scratching their heads. We see blood spots. We don’t actually see the corporal damage, the wounded, maimed, and dead. We’ve lost our ability to face this reality. That’s been going on for a very long time. It’s not without reason that so many of our horror movies are about the dead not being able to die. They keep coming back. Part of it is that we never see dead. We don’t know dead, so it keeps coming back.

BLVR: This would be a place where you’d think a figure painter could step in—

EF: —and contribute—

BLVR: —and, as you said earlier, memorialize.

EF: I wish I could.

BLVR: I think Tumbling Woman did do that. And it must have been hard to be suspected of trying to be merely controversial.

EF: To be accused of it! For that to be thought of as my motive was very hard. That the piece was disturbing is OK. It is disturbing. But to be accused of it being sensational—like, “This is the artist that bought you Bad Boy.” But what can you do? The older I get, the more I should learn that there are appropriate times for certain things. Maybe I had rushed it. I don’t know.

BLVR: Maybe art isn’t capable of memorializing anymore. I can’t even think of recent art that deals with death.

EF: Warhol did it in an ironic way with car crashes and electric chairs. I don’t believe that art can’t. If the audience can’t face death in its physical form, if we can’t handle looking at it, it makes it harder and harder. But I think it’s necessary. It’s a social glue that holds communities together—that kind of sharing. I think that the problem with photography is that there is a certain kind of distance that tends to alienate. You don’t see the artist connected on the other side of the painting. That’s what you want memorials of all kinds to do—to connect you. It becomes a public suffering, a public lament, a public celebration, not a private one.

BLVR: At the same time as the sculpture, you were doing a series of figurative watercolors. But unlike your paintings, your watercolors float or tumble in space. There is no backdrop, which is really a cornerstone of your early work—definite locales.

EF: I think it’s the difference between painting and sculpture. I found with the watercolor drawings, when I first started, that they were better informing my sculpture than they were my painting. It’s the nature of sculpture itself to try to contain within its form the whole story or experience. Going back to the Tumbling Woman experience, that sculpture was put in the concourse of Rockefeller Center. It was dropped there. It was a place where people are going to and from work, eating, and the like. It happened to be on the backside wall of Prometheus. Prometheus is soaring into the heavens as the giver of life. And on the backside of it is a charred figure falling into itself—the total opposite. Metaphorically it was perfect. But people were really upset. It wasn’t that they were saying, “This isn’t art.” They were saying, “This is art. It should be in a museum,” which I find really saddening. Why ghettoize art? Why not keep it within the public boundary?

BLVR: That really questions whether public art can be overtly political. The sense is that one shouldn’t have to deal with art on a lunch break.

EF: And I agree with that in a lot of cases. But, on the day of the memorial, I leave my house and I’m walking through my studio in Washington Square Park and the names of the dead are being read down at Ground Zero and radios are on and people are listening. I hear, walking past the dentist’s office, names filtering out. And through the park, people are on a bench listening with a ghetto-blaster tuned to the station. Names are wafting out in the park. All the way from my studio, the names, the ghosts of the dead, are coming out and floating through the city. The whole city is filled with the ghosts of the dead. It was incredibly powerful experience. In the place I’m walking, the dead are being remembered.