Eve Sussman, the woman behind this year’s Whitney Biennial darling, 89 Seconds at Alcazar, has just returned home from Athens, Greece, where she and two collaborators (Claudia de Serpa Soares and Jeff Wood) auditioned two hundred people in a four-day casting frenzy. Sussman’s most recent project (working title: Raptus) is inspired by Jacques-Louis David’s painting, the Intervention of the Sabine Women, much as her acclaimed 89 Seconds video paid tribute to painter Diego Velazquez’s Las Meninas. After folding the newest Greek cast members into their expanding, intergenerational, transnational pack of performers and artists, Sussman and her co-conspirators moved through Greece for three weeks under the evolving entity of the Rufus Corporation. In her own manifesto/press release, she states:

The Rufus Corporation, a band of itinerant actors, artists, dancers, musicians now totaling twenty-two—having added twelve performers, two horses, an opera singer and a cowboy to their ranks—ascend two hours to Episkopi… in the mountains of Hydra, to the estate of the late cigarette mogul, Papastratos, who graciously abandoned his summer home in the late sixties leaving a perfect time capsule and testament to the glory days of the Athenian entrepreneurial class… as if anticipating the arrival of a group of wandering bards in the early part of the twenty-first Century.

—From “What Is the Rufus Corporation

and Who Are the Sabine Women?”

We met in her home/studio, a large, open space overlooking the Wallabout Channel in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where we discussed her work-in-progress. While talking to her about her developing opera-cum-musical, I flashed between images from various black-and-white Greek musicals I watched day after day while visiting Athens in the mid-nineties. Sussman hadn’t seen any Greek movies from this era, but was assiduously culling ideas from other cinematic influences, along with architectural, musical, operatic, sculptural, and (once again) painterly sources.

—Suzanne Snider

I.“PEOPLE HAVE WHAT THEY SAY IS A NORMAL CONVERSATION BUT TO ANYONE WHO DOESN’T SPEAK GREEK, IT SEEMS LIKE THEY’RE HAVING A FIGHT.”

THE BELIEVER: Is it a tragedy?

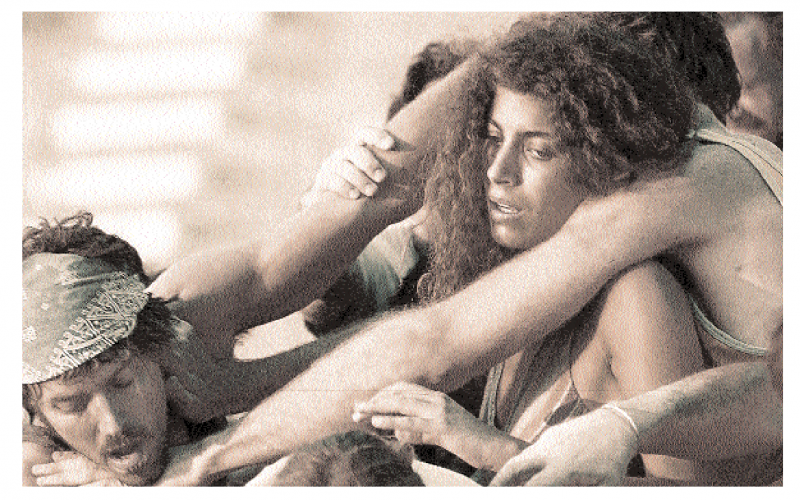

EVE SUSSMAN: Yeah, probably it is. The new piece is based on the myth of the Sabine women. These women are stolen from these men and the men go back to create a war to win back their women. And instead of going back to their homeland, these women just separate the two groups of men, and in some ways that act’s pretty confounding. In the group dynamic that we had [in Athens], the men did form into packs, and the women were sort of filtering between and that just happened socially. You watch it as a strange psychological and sociological study of what happens when you put people in a room. And that’s the thing I was most interested in with 89 Seconds. What would have been going on in this room? I feel like I could make films about that forever—what’s the psychological condition when you walk into a room full of people, and how do you capture that? What are the tensions in the room? What are the love affairs in the room? What was the backstory before you walked in? Where is the energy going?

BLVR: How did you decide where to set it?

ES: The myth of the Sabine women is actually a Roman myth, but you could set it anywhere. I felt strongly that I wanted to do it in Greece—at first it was intuition. People asked, “Why Greece?” I had more obvious reasons, but when I finally took my company and we cast our other Greek actors, I think people understood why I felt it was important to work there. For me, it had to do with some hokey idea of collective unconscious and the idea that there is this layered history that people carry with them. In Greece, that collective unconscious, that shared history, is really prominent. There is an overall consciousness of ancient history and the sense that you live in a shot of these ancient sites, and you use them. We’re now trying to get permission to use the Herodion Theater at the Acropolis to do the fight scene in that amphitheater. And the idea that that’s been used for 2,000 years is kind of phenomenal. I had lived in Rome and in Istanbul, and Athens puts you right in the middle. It somehow felt important to me to be right in the middle between these two cultures that I was familiar with. I put myself in a place where I was unfamiliar to the point where I couldn’t even read the alphabet. Instead of going to a place where I knew people and had connections and spoke the language, I went to a place where I knew no one and understood nothing, but I had a feeling about this idea of shared history and collective unconscious and I had a feeling about the landscape. The landscape in Italy was much too bucolic— much too soft, much too sweet. And I thought the lifestyle in Italy also was not quite rugged enough. I felt I needed a more raw environment. In parts of Greece that’s still true. In parts of Athens, it’s really intense; people talk about it as a polluted, aggressive, and loud city. It’s actually less aggressive than I could have imagined, but it is an aggressive place—I mean, it rivals New York in terms of being noisy. People have what they call a normal conversation, but to anyone who doesn’t speak Greek it seems like they’re having a fight. So it is really a different culture and it’s not a very European culture. Greek friends of mine say,“we were raised being told we were Balkan, not European.” And it feels much more Oriental and Turkish than European. That was important to me for this piece, too.That we get away from the domesticity and conformity of a lot of European culture. In Greece, nobody quite conforms—there aren’t really any rules on how to do anything.

BLVR: And they break plates! I love a country that breaks plates to show joy.

ES: I didn’t see anyone breaking plates but I can imagine. Maybe we’ll have to use that.

BLVR: You called your new piece-in-progress an opera. How are you defining that term?

ES: I want it to be driven by voice and music in the broadest way possible. We’ve experimented with a bunch of different choral ideas. Jonathan Bepler was talking about having a baby chorus, a man’s chorus, and a woman’s chorus. And an animal chorus. We’re talking about setting part of the new piece in the marketplace. In Athens, we went into the meat market—which is huge, with this cacophony of sound—it’s really medieval. You have goat heads and pig’s feet and slabs of lamb and beef and guys with knives this big [gestures impressively] and they’re all screaming. We just went in there and started doing musical improv with them. We were walking through the market in groups with Jonathan leading the groups and having them do different sound improvs based on the sounds they were hearing. We threw in some traditional Greek instruments like bouzouki and some percussive instruments.

BLVR: How did that work out?

ES: It was cool. We played around a lot with bells, too. At one point, we were doing a bunch of fight choreography where everyone had bells attached to them. That was based on Jonathan’s interest in the way you always hear bells in the landscape in Greece, once you get out of the city and are into the countryside. We attached bells to all the actors.

II. “AS IF SOMEBODY HAD WALKED OUT OF THE HOUSE IN 1965 FOR A CUP OF COFFEE AND NEVER CAME BACK.”

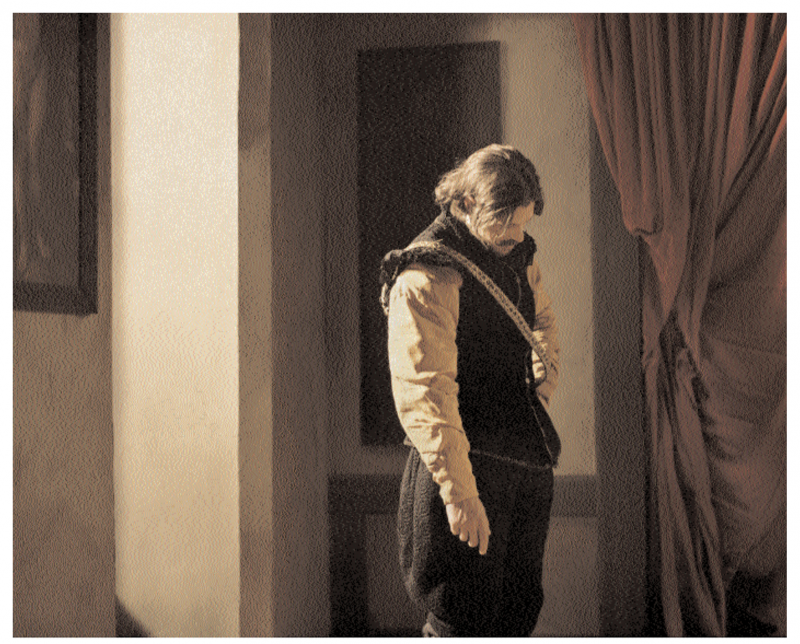

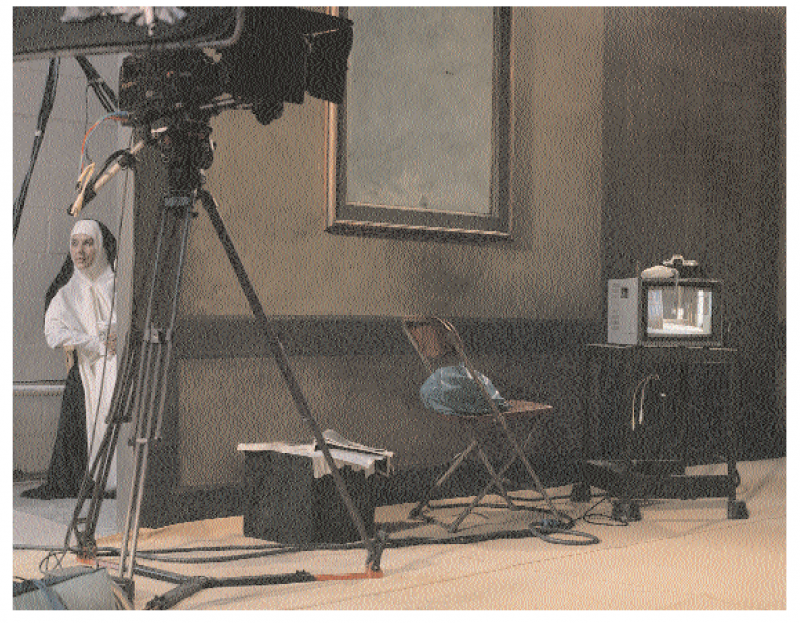

ES: Last time, we tried to quote a painting and tried to quote it as carefully as possible. This time, we looked at a painting [David’s The Intervention of the Sabine Women] and thought, “Well, that’s a cool myth.” The initial impetus for the piece was: I saw the painting, I emailed it to my choreographer Claudia and said. “OK, this is the next project.” And she said, “You’ve got to be crazy.” I thought this would be amazing fight-choreography, an awesome possibility to do it as this huge operatic moment. But the more I thought about it and tried to couch it in this early-modern thing, [the more] I became more interested in not quoting the painting at all, and instead looking at filmmakers like Antonioni and Godard. Start in 35mm black-and-white and let that morph so that by the end of the piece you’re in this really loud, garish, HD-color riot scene.

BLVR: How did you find the specific location once you decided on Greece?

ES: We somehow lucked upon this estate that was built by Papastratos, who was the big cigarette mogul in Greece, in the first half of the twentieth century. We’ve gotten permission to film on this ranch that he built up in the mountains on Hydra, which has three houses, the last of which was built in 1932 by this very famous Greek architect, this beautiful slicked-down early-modern house in this phenomenal setting. That’s going to be one of our prime locations. The really interesting thing about the location was that the guy who owns it, and who took us there, stopped using it in 1965. Nobody had been at the property for forty years. Three years ago, he went back to this old estate and walked into the house. And it was as if somebody had walked out of the house in 1965 for a cup of coffee and never came back. All the products, everything in the kitchen, the bathrooms, all the magazines, everything on the shelves, were all from 1965.

BLVR: Did he chuck it?

ES: He has it all. He has the Time-Life magazines, the Greek magazines, all the toiletries. There was perfume and powder and Tampax and mosquito spray.

BLVR: Who was he that he was historically conscious enough to keep all the products?

ES: The grandson of Papastratos, who is from one of the richest empires in Greece.

BLVR: And is that his full-time gig? How did you hook up with him?

ES: You know, we hooked up with everyone you might need to know in Athens. We got really, really lucky.

BLVR: Is that because you were very visible there— wearing bells?

ES: It’s a very cosmopolitan city, and as a group I don’t think we were that visible. But we were talking to a lot of people.

BLVR: And wearing bells.

ES: I think it was karmic, or about luck. We lucked into this amazing apartment in Athens in this landmarked building; the owner had bought it three months ago. He happened to be an editor of an art magazine in Athens. He called me up one day—we were in Hydra working—and said, “What are you doing?” and I said, “Oh, we came here to do a little residency for a week” and he said, “Oh, well, you have to call my friend Sotirus, he’ll take you horseback riding.” I said, “I hope Sotirus knows we’re twenty-two people,” and this was including one ten-year-old and two members over sixty. He said, “Just call him, it’ll be fine.” The thing about Hydra is that there are no cars, so you’re going on foot or on horseback or donkey and this estate that he repossessed three years ago is a two-hour walk from the port, so you’re either walking or going on horseback. No motorized vehicles are allowed on Hydra. There are three dump trucks—those are the only motorized vehicles on the island. Which is why it’s a celebrity island. Brice Marden owns three houses there. Leonard Cohen owns houses there.

III. “I’D FILL A ROOM WITH WATER OR I’D MAKE AN ALLEYWAY THAT WAS A FORGOTTEN STREET INTO A CANAL.”

BLVR: You’ve referred to the group as a company. If you continue to have this core group of people moving from project to project, does it take away from watching new dynamics if you’re watching people socially interact, [always] looking for that awkwardness?

ES: I don’t really know. It’s sort of an ad-hoc company. I was trying to write a press release for this new thing, and it started out with “What is the Rufus Corporation and who are the Sabine women?” In a way, if I could answer both of those questions, we would know better what we were doing.

BLVR: It’s a compelling line.

ES: In a way, my goal is the answer to those questions and maybe that’s what we’ll do in the next six months. I think the company is kind of ad hoc and always changing. And that doesn’t mean I won’t do the next piece totally alone, shoot the next piece on the street with a surveillance camera, which is what I used to do. The Rufus Corporation is more of a concept than it is a solid group of people. Maybe the way you keep the strangeness is that the company keeps growing. The other way you keep the strangeness is you keep moving from country to country.

BLVR: I was going to ask about location because this is obviously different—you built your 89 Seconds set in Williamsburg.

ES: Right in Williamsburg. I knew where everything was and could call anyone at the drop of a hat. I was working in my native language.

BLVR: Now you’re working in Athens but I also read that you did a project in Lomé.

ES: I shot a little film there. I was traveling a lot to West Africa. It’s a Super-8 piece that I created from footage that I shot there. It was much more the run-and-gun style of shooting that I really like doing. I would like to be able to do both. In a way, I was just doing both. In West Africa, six or seven years ago, I was shooting constantly and then trying to find the story afterwards. I love doing that. I think that things keep changing. You keep rearranging people and adding new people, but I think that changing location is really important. I’ve traveled a lot throughout my life, so I feel like keeping moving is a lot of what it’s about.

BLVR: You told me earlier that you started as a photographer at Bennington.

ES: Yeah, at school I was a printmaker and a photographer.

BLVR: And what was your trajectory after that?

ES: Oh, god. Sculptor. And builder. Making my living by renovating buildings—I’ve done that for a long time. That’s part of my interest in working with architecture. I was a sort of sculpture installation-artist— I still kind of consider myself that. Maybe the best description I have is from a friend who introduces me by saying: “This is Eve. She’s a sculptor who shoots film.” I think, in a way, a sculptor who shoots film is a better description than a video artist or a filmmaker, because I’m interested in finding a great piece of architecture and asking: How do you work in that space? As an installation artist, I often take a place and change it; I take out a window and build a ramp out of the window and build a tower that is a viewing platform for the audience. Or, I’ll fill a room with water or I’ll make an alleyway that’s a forgotten street into a canal.

BLVR: You used the term “video artist,” and mentioned that it makes you uncomfortable. Why is that?

ES: All of the characteristics of what I’m doing seem like they fall more easily into the concerns that surround filmmaking as opposed to what you would think of as video art. It gets very blurry. That blurriness is really interesting to me and that’s why I’m trying to bridge the gap—trying to have a foot in both worlds. But it’s not as easy as one would think. In a movie theater, people are a little more tense. They’re really expecting to be entertained. With video art, you’re not quite expecting to be entertained. And when you are entertained, you’re really pleasantly surprised. Video art demands a certain kind of patience and forgiveness from the viewer. You have to allow yourself to sit for a certain amount of time. You might have to accept that you’ll be bored for a while. It’s rare that you get emotionally involved during a piece of video art the way you do at the movies. There’s that idea that you’re able to leave at any point with a piece of video art. If you go to a movie, you’re almost buckled in. To walk out of a movie is a huge statement. Even if the movie sucks, you’re always debating: Should I walk out? Is it rude? Is everyone going to notice? I’ve only done it once or twice in my life because I feel like even if it sucks, I should sit through it and I’ll learn something. And I want to see who’s in the credits.

BLVR: Do you want to change people’s expectations? Or do you want to surprise or subvert those expectations?

ES: I guess I’m more interested in subverting those expectations and surprising people. I would love if you went to a piece of video art and got emotionally involved the way you do at the movies. You’re not expecting that to happen, so the emotional involvement is much more shocking. I guess I’m saying I really want to be a filmmaker, but then, am I playing the wrong field? Am I in the wrong world? On the one hand, it doesn’t even matter. The only place genre matters is where you’re trying to explain to people what you do or when you try to raise money. Then people want you to categorize yourself. That’s where I find that more and more difficult. It would be so great to not have to answer those questions.

IV. “WE GOT SADDLED WITH A TWO-HUNDRED-TON BOAT.”

BLVR: I was told to ask you about tugboats. Is that code for something?

ES: [Laughs] No, it’s literal, unfortunately. We owned an eighty-seven-foot tug for about four years. I know. This is a whole other theory I have about…

BLVR: About tugboats?

ES: No, it’s a group-dynamic theory. What happens when you put twenty people on a boat? I got really seduced by the idea of owning a tugboat, and crazily enough, three of us—my husband Simon [Lee] and a friend of ours, Peter Lundberg, a sculptor—bought a tugboat. And little did we know what we were getting into. It’s kind of a dream I have, to live in an urban environment but also to live off the grid. I think your whole state of mind is changed when you’re on the water, even when you’re tied to land and not moving; when you step onto a boat, it’s such a psychologically different state and I’m not sure why. I think you just feel more free. But that didn’t change the fact that we got saddled with a two-hundred-ton boat. It was a huge money pit, and the only way we could have made it work was to make it as a nonprofit, as an artists’ residency. It would have worked—it was beginning to work—it was floating. It wasn’t running, which is why we were able to afford it. We bought it for very little money and sold it for even less. It was sort of a sad story. Ultimately, it was kind of a failure. I think if one of us were able to devote enough time to it, we could have made it work. And I think we could have made it work as a nonprofit; we could have raised money for it. We were getting a lot of attention for it as an artists’ residency.

BLVR: Did that ever happen?

ES: We had people staying on the boat. Our friend Pete had a sculpture park in Connecticut and for a while we had her up there. People would stay in the boat and make work for the sculpture park.

BLVR: How did the boat get to Connecticut?

ES: We towed her. For a year she was right out here [points to the water] in Wallabout Channel, which looks very calm but is actually very dangerous. It has a really broad tidal swell, an eight-foot tidal shift. The currents are much swifter than you would imagine. We made a deal with the lumberyard out there.

BLVR: That’s such a pioneer fantasy.

ES: Yeah. There are some people who do it rather successfully .A couple of people we know have boats in the Hudson, right off of Chelsea piers, but that’s kind of all they do—that’s their artwork. For Pete, Simon, and me, it became ridiculous because we all had other things going on. We had to get rid of her. It was really sad. If we did it again, we’d have to go into it with a lot more money. The amount of money we spent in those three years was kind of ridiculous, and she was never really livable. We kind of camped on her in the summertime, up in Connecticut, but it wasn’t really a viable option for a place to live. I still imagine it could work. We did Thanksgiving on the boat one year. We had nineteen people doing Thanksgiving on her. I’ll show you a picture. She’s lovely. Being really close to the water is very important to me.

V. “THE WAY YOU CAN DEFINE YOUR EMOTIONAL EXISTENCE IS BASED ON TEN WORDS OR SOMETHING.”

ES: The real transition point was 1995. I did a piece on Roosevelt Island. It was a configuration of six mirrors that worked as a giant periscope. The biggest mirror was kind of like a drive-in-movie screen—it was cantilevered off the side of a building. And it was positioned in such a way that if you were inside the building, you could see what was happening. If you were outside of the building, you could see what was happening inside and if you were inside, you could see the river. What was great was to do this giant mirror like a drive-in movie screen. For me, that was kind of transitional. The whole time I had been shooting film and video. I started shooting Super-8 when I was like seventeen or eighteen, and shot a lot from the mid-eighties until now. I still shoot a lot with Super-8 and with surveillance cameras—I did a lot of pieces with surveillance cameras. I did a piece in the Istanbul biennial in ’97 that used twelve live-feed surveillance cameras, and I cabled the entire train station. My first solo show at Bronwyn Keenan, also in ’97, was with live-feed surveillance cameras, and I was surveying pigeons in this light-well. It was this tiny little gallery, and it looked out on this typical view where you see just the building— an air shaft. But the air shaft was filled with birds. That was where I took out the window and built a ramp out the window, so you could go out and watch the birds in the air shaft. But everything was under surveillance as well. When the viewers went out on the viewing platform, they were under surveillance and it was all projected inside the gallery. If you could put together groups of people all the time and just watch them, it would be eternally interesting to me. It would never get boring. I’m trying to figure out how to keep that going.

BLVR: Do you think there are a finite number of ways we interact and deal with social situations? Do you think it’s predictable?

ES: I think there are a finite number of emotions. Of course, technology grows, the world keeps changing, and there’s a scientific knowledge base that keeps growing. Your social dynamic keeps changing and what’s considered acceptable keeps changing. But I think our emotional life is no different than it was a few thousand years ago. I think the way you can define your emotional existence is based on ten words or something.

BLVR: Do you find that liberating or devastating?

ES: It’s not liberating or devastating. I think that’s just the way it is. I think it’s just really interesting. I think society keeps changing and the world as we know it, in theory, keeps changing, but the thing that doesn’t change is how you feel. I don’t think there’s a new emotion. I don’t think you can invent a new feeling that didn’t exist a thousand years ago.

BLVR: That makes me think of Vladimir Propp’s literary theory based on the folktale where the author specifically asserts that there are a finite number of narratives in existence and you can never get out of this finite number.

ES: Which is sort of the same thing.

BLVR: There are only so many ways a story can go.

ES: Which is why you can take a basic idea, like a love story or a war story, and there’ll be quintessential themes, and it’s really hard to stray from them. And even if you think you’ve strayed from them, you really haven’t. Which is why I find those narrative themes are less interesting to me and the way people interact within them is what’s more interesting.