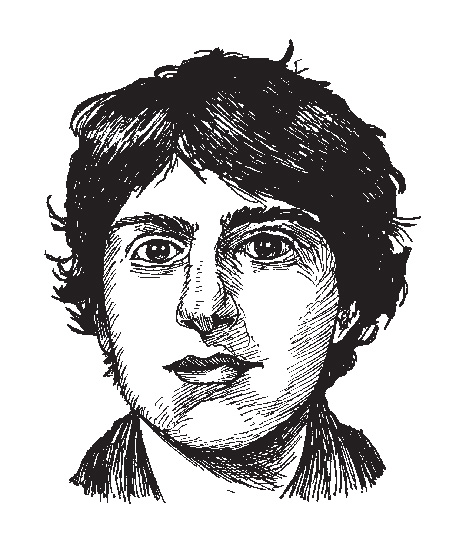

Ezra Koenig is a smartly dressed, culturally savvy rock musician living in the age of hip-hop. His band, Vampire Weekend, has released three widely successful albums (a trilogy, as he thinks of them) since 2008, when they rose out of the golden age of innovative Brooklyn bands. Unlike many of their contemporaries—Dirty Projectors, Animal Collective, Grizzly Bear—who gained audiences primarily through the independent-music community, VW attracted mainstream attention and were quickly received by the broader pop music world. This could be attributed to their songwriting—a lot of old-fashioned, three-minute foot-tappers—but also to their media-friendly aesthetic, which can be described as preppy and worldly and is expressed equally in their fashion (cardigans, popped collars), musical style, and song titles, such as “Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa.”

The band’s sound is a nimble and clean variety of pop rock that has grown in subtlety and richness over the last eight years. For his part, Koenig plays guitar, often like a South African from the ’80s, and sings like a talky choirboy with an Ivy League English degree, which he has. His musical persona is more like an observational journalist than a confessional songwriter, and he frequently diagrams his life experiences through the media around him. His songs, often lyrically led, are erudite, poetic collages of cultural references to designer brands, ethnic foods, cars, technology, ’70s films, and international news tidbits.

Koenig is a connoisseur of pop culture. He sees himself as breaking from the archetype of the rebellious, reluctant rock star and embracing pop as a fertile ground for creativity. He isn’t an outsider dragged into the mainstream, conflicted about selling out. For him, the outsider is an anachronistic role and rock and roll is a cold corpse in the ground.

I met Koenig twice for breakfast at the Noho Star, in downtown Manhattan. The first time we discussed summer singles, Kanye West, and Taylor Swift. Because of this interview’s delay in publication, Koenig found his cultural references too dated and asked to meet again to discuss the current pop climate. Further delays ensued.

—Ross Simonini

I. “ALMOST ANY GOOD MUSIC IS POP MUSIC”

EZRA KOENIG: What were you saying?

THE BELIEVER: I’d asked if you enjoyed touring.

EK: Sometimes I do, sometimes I don’t. For me right now, it feels like the end of an era. Just finished three albums, just turned thirty, you know? I associate a lot of the past touring with stress and existential fear, like: will the band continue to exist? Will people like it? Am I a worthwhile person and artist? I have a feeling that as this era comes to an end, the next one will be a little less fraught, just because, no matter what, we’ve released three albums. I’ve always had this feeling that three albums makes a real catalog, whereas, unfortunately, one album—even if it’s an amazing album—often doesn’t mean much in the long run.

BLVR: Are you dealing with your own thoughts onstage much?

EK: I’ve gone through dark periods when—who knows why?—I was just very unhappy and wasn’t psyched to be on tour. And then sometimes when I would be onstage, it would become a weird, quiet, meditative moment, even though I was surrounded by people. In the best shows, though, you’re really in there with the crowd and not worrying about, Is this album is a success? Is it good? Did it work? But I’ve noticed a lot of people tend to enjoy touring more as they get older.

BLVR: That seems surprising, since it’s so tough on the body.

EK: I feel like a lot of these sensitive souls—sensitive artistic spirits like Thom Yorke and Bob Dylan, people who you could easily imagine pulling a J. D. Salinger and who in their twenties often seemed very cagey—they tend to shift gears. You watch Meeting People Is Easy, and Thom Yorke is backstage all stressed out and doesn’t want to be there. And yet as these guys get older, you find that they are very consistently on the road. I think it’s that they start to realize there is something that is important about live performance to them… or maybe it’s just the money. I watched that National documentary, and there’s a part where they have a bunch of technical problems during a big show, and the singer comes offstage and is very angry, and his brother, who is filming the documentary, is annoying him. He’s trying to get into a room and there’s a coatrack blocking the door and he’s so frustrated about the show that he just tosses the whole thing on the ground and walks away in a huff. I saw that and part of me was like, Oh, I know exactly how he feels, but, of course, when you watch somebody else do it, it seems a little bit absurd because its like, Come on, nobody else feels as bad as you. Chill out, dude. My hope is that it all feels a little less high stakes in the future.

BLVR: I remember my first experience of seeing a band perfectly perform their set. They played an album, note for note, and I realized, once I saw it done, that I didn’t care about perfection.

EK: Its like on the last Kanye tour, you know, the so-called rants? I saw one show when he talked for a pretty long time and a lot of people went to the bathroom or to buy hot dogs then, but in some ways it was my favorite part of the show.

BLVR: Are you a fan of pop music today?

EK: More or less. I like to follow what’s going on. I like the stories and the personalities. To me, almost any good music is pop music.

BLVR: What about, say, new classical composers?

EK: Most of that stuff is not good, but Philip Glass in the ’80s was almost on some pop-type shit. He was a character in the world and he was part of the pop conversation. I’m just interested in personalities and figures. Occasionally the music feels incidental.

BLVR: To the personality?

EK: You know that Kesha and Pitbull song that some people think is horrible, called “Timber”? It’s a weird countryish dance song with a catchy harmonica part and people ask, “Do you like this song?” I’m interested in talking about the song—the meaning, the moment, the personalities of the singers—but who cares if I like it or not? When I go home and listen to music, I like to listen to, maybe, an old ’40s recording of “Danny Boy.” That’s the music that makes me feel in touch with the sublime, but I don’t hold it above Pitbull. Personally, I just like to listen to the same songs over again: the Clancy Brothers, Irish folk songs, stuff like that.

BLVR: Have you always listened to that kind of music?

EK: Yeah, for maybe about fifteen years or something. I return to those types of things. But again, that’s just what fills that slot for me. If I wake up early and I’m on a train and I’m feeling wistful, I listen to old recordings of “Danny Boy” or “The Minstrel Boy”… or some other Irish song about a boy. That fills a spiritual need for me.

II. “FRONTING IS UNFORGIVABLE”

BLVR: I want to ask you about your relationship with Twitter. It’s a way of constructing a public personality, and depending on how you do it, the persona could compete with your music or work in tandem with it. People tend to have problems when there is a friction between the two. How do you negotiate this?

EK: I think generally people just don’t like phonies. In that sense, nothing has changed in sixty years. When a certain element of somebody’s persona seems truly antithetical to some other element, then it confuses people, or bothers them. I’ve thought a lot about how when Lana Del Rey first came out, there were a lot of people trying to say that she was a phony because maybe she had plastic surgery, maybe she changed her name, maybe she was from upstate New York and not 1950s Hollywood. Yet these attempts to call her phony all fell very flat, because she didn’t actually feel phony. There’s a difference between a devious liar and somebody who is just being a great artist. You’re allowed to make up certain things as an artist.

BLVR: How do you think the new criteria for persona compares to old Hollywood persona?

EK: I think today you can be whoever you want to be, but it has to be a little bit fluid. Lana Del Rey can pretend—borrow elements of old, glamorous Hollywood—but if we got the impression that she was mentally ill and insisting that the world believe that she did not have a real name and did not have a history, we would feel differently. She doesn’t seem to insist on that. People who grew up on the internet intuitively understand the idea of having fluid personas. I don’t think fans would think it’s weird that I don’t dress super preppy all the time. People are OK with a bit of role-playing and showing different sides of your personality. I think that the greatest sin is just fronting. Fronting is unforgivable.

BLVR: Which just means that in daily life you’re doing it?

EK: Some people do it artistically.

BLVR: What’s an example of that?

EK: I feel a lot closer to artists who craft a whimsical persona than to artists who craft a boring persona by lying or downplaying their own background. With Vampire Weekend, the initial idea was somewhat aspirational. When a lot of people were starting to write about us and it was, whatever, “Rich kids from Columbia!” I remember I had a friend that I grew up with who said to me, “Oh, I like your new band. It seems very aspirational,” which I thought was [laughs] borderline offensive. But then I also thought, No, he’s right. He grew up with me and he knows there is something about dressing above your means. He could see that was a part of it, as opposed to—maybe I’m getting too philosophical.

BLVR: He saw it as a role, whereas other people saw it as you just projecting yourself at a loud volume?

EK: I have mixed feelings about materialism. It brings me a lot of joy: material things, beautiful objects, luxury objects. I can’t say I’ve graduated from the material world. One thing I can say is, I think when somebody aspires to own a fancy sweater or a nice watch, there is something very honest about it, because it’s recognizing that our world is materialistic and status-oriented. There is only a little bit of joy that you can find in this world. Sometimes looking for an object is all that we can do, so when somebody desperately wants to dress in a way that signals that they are richer than they are, that they are more elegant than they are, that they are more mysterious than they are, I can’t knock it, because that’s the real world. Whereas on the flip side, when an artist who comes from a privileged background dresses and acts in a way to deny or obscure the privilege, to me that’s pure wickedness, because they’re lying about how the world works. I think rich people have a responsibility to be honest about their backgrounds, whereas if the non-rich want to dress up and pretend to be rich every now and then, go for it; who cares? So basically, shady slumming is about as bad as it gets.

BLVR: What about a rich person who renounces materialism and becomes a monk?

EK: Well, those are some of the greatest people in history.

BLVR: They’re not fronting?

EK: No, they’re not fronting: that’s as real as it gets. That’s the one thing that people born rich have over people who are not born rich: they are born at the top of the mountain and therefore they can make a different type of sacrifice. That’s what Siddhartha was. And truthfully, the story of Siddhartha would not have been as compelling if he’d been born poor, stayed poor, and meditated by a tree.

BLVR: Your lyrics sometimes come out of tweets. Is the compulsion to write a lyric the same as the compulsion to write a tweet?

EK: I’ve actually just been working on a song based on something that I tweeted years ago. It’s all just language. They strike me as two things that go together perfectly. My lyrics are not 100 percent autobiographical, but they’re 100 percent a part of me. Same with anything I’d write, a tweet or an email or a text or anything. It actually seems weird to me that somebody who writes words for a living would be scared of Twitter undercutting that.

BLVR: You posted a poem recently on Twitter. Do you ever write lyrics as stand-alone pieces?

EK: I feel like it’s really all the same thing. Do you enjoy words? Do phrases pop out of TV shows or books or conversations? Do you want to remember these phrases? Either you’re into that or you’re not. Other people feel that way about colors or shapes or fabrics or sports trivia, but if you’re into words and phrases then it makes sense that you would occasionally write a little poem, take little notes, write little tweets, write little things that become songs—you know, it all seems related. But I really don’t sit around specifically writing poetry too often. If I was born in the ’40s, maybe I would have been obsessed with Allen Ginsberg instead of the Beastie Boys.

BLVR: Do you read poetry? Are you much of a reader in general?

EK: I try to be. It comes and goes. When we’re working on an album I become very obsessive and everything I do has to serve the album, so if I feel like reading a book will help me, I’ll do it; if I feel like it will distract me, I won’t do it. Then usually you get on the road and you’re spending more time on planes and stuff, and you start reading books more freely again, so I’d say I’m probably a very average reader. Maybe based on the alarmist articles I’ve read, I read more than the average American. You know [laughs], people say that the average person reads, like, whatever, less than ten books a year: then maybe I’m above average. Anyway, we all read a million little things a day. A really short Emily Dickinson poem here and there. I’ve been trying to read this seven-hundred-page Emily Dickinson biography for years, like two years. I have it on my Kindle, so I read a tiny bit here and there. But I’m not mad; I don’t beat myself up about it. I guess people say you do your brain a favor, though, when you read a big-ass book.

BLVR: Do you have any leanings as a reader? When you do read?

EK: Sometimes I’ll get on a real nonfiction kick and be obsessed with a certain topic. When we made our second album, Contra, at a certain point I thought, I like this name; it feels like the right name. I like the meaning of the word, you know, the Spanish word contra. I liked the reference to the video game Contra, but I wondered, Are people going to think this is a shout-out to Reagan-backed, anti-communist guerrillas in Nicaragua? I needed to know the ins and outs of the associations that people have with the word, and so I obsessively read about the Sandinistas and ’80s Nicaragua for a while and, who knows how, but in some way I feel like that helped me with what I had to do for the record. I like those periods because sometimes it’s good to just read about the same thing over and over again for a while. Like, after Nelson Mandela died, like a lot of people, I was thinking about him a lot. I read his memoirs, and books about him, but then I was like, What was the deal with the pro-apartheid Afrikaners back then? Like, where was their whole headspace coming from? And I was like, Fuck, I’ve gotta read some books about these dudes. And to even remotely begin to understand something, you need to go pretty deep. When I was reading, like, the seventh book on South Africa, some part of me was like, Man, what am I doing? Am I going to go to South Africa? Why am I reading a third book about the African National Congress when I haven’t even read some supposed American classic like The Scarlet Letter or something? But sometimes the better you understand one thing, the better you understand the whole world. As you read that stuff, you start to realize that there are so many parallels you can draw between that situation in South Africa and other parts of the world today. Like Siddhartha said, under a tree he learned how to understand the whole universe, whereas some idiots who’ve been everywhere don’t know anything. As a touring musician, sometimes you feel like you’ve been everywhere, but you really don’t know shit.

BLVR: How do you start an album?

EK: I’ve been thinking about the fourth album recently, and at first it feels like you’re totally groping in the darkness. It’s scary and you wonder, Will we even be able to make another album? And then I went back to a demo that Rostam [Batmanglij] and I had made for the last album, and I was looking at some of these lyric fragments, some of which were even older than the demo, and suddenly I saw this, like, meaning in it and I suddenly had this feeling: 2014, let’s do this! [Laughs] It all made sense. Why should we pursue this at this moment in time? Why is it worth making another album? What is the meaning? Suddenly it all came together, so now I feel like there is a guiding principle for the next album, even though there are basically no songs.

III. LANDLORD RAP

BLVR: Your music is filled with timely signifiers.

EK: It’s been a conversation that has come up over the years, the question of how valuable is this thing that we call “timelessness.” We grow up reading positive reviews of works of art that are called timeless. We saw those commercials all the time: “timeless classics on CD.” But that just seems impossible to me. All music is connected to the moment it was made. Like, in the early ’60s, you have surf music, something that is using new technology, reverb, and electric guitars to create something that you’ve never really heard before, and then you also have Bob Dylan poring over old folk songs, recording with just an acoustic guitar and his voice and using weird, outdated phrases like a-changing. Yet now, we look back and think, Surf music: does that feel like early ’60s? Yep. Bob Dylan: does that feel like early ’60s? Yep. Because that’s when it’s from. It doesn’t matter if Bob Dylan might have been up in the library researching the 1880s or whatever. He is still a fucking ’60s dude, just like the Ventures. While working on our second album, I remember specifically having this thought: The idea of timelessness is bullshit. It’s totally overrated. If our music sounds dated in five years, good, thank god. I was on this Bret Easton Ellis podcast and this came up, the idea of timelessness. He was saying that when he was in his writing workshop in college, the teacher told him, “Hey, man, you’re constantly referencing specific products and albums. Your work is going to age very poorly,” and I was thinking, That guy was fucking wrong, because actually people today read American Psycho and read those really specific descriptions of Phil Collins albums, references to specific brands and stuff, and feel that it’s aged very well, whereas whoever in the ’80s was trying to write some kind of timeless shit—that must be so boring. And also people often misuse the word timeless; it’s like, “Timeless to who?” To some people, Bob Dylan is timeless: acoustic guitar, plaintive singing. We say it’s timeless, but why is that timeless? Why is that the year zero? Year zero for who? It’s year zero for baby boomers. Is Bob Dylan timeless for my grandma? Or the millions of people who are now passed away from this earth? Were Bob Dylan’s ancestors in Eastern Europe singing those types of folk songs? Like, my friend is German and she grew up in Frankfurt, where for people her age there is that tradition of minimalist techno associated with very specific clubs. They have their own year zero, their own idea of what is timeless. For them, there is such a thing as timeless, back-to-basics, good, minimalist dance music. For them going to a club was part of a multigenerational sense of cultural identity. Dancing to electronic music can be timeless, too, but if you set your year zero to acoustic guitar music, you’ll never understand that. On our last album, we got less interested in synths and auto-tune and stuff like that, but to say that we wanted the third album to sound more timeless is buying back into this whole myth. We didn’t want it to sound more timeless; we wanted it to sound more ’60s and analog. That’s what it is: it’s not timeless. It’s yet another reference. Yeah, so it’s taken me a while, but I’ve increasingly become hostile to this imperial idea of timelessness.

BLVR: Do you think about the music as purposely referential?

EK: Yeah, sure, but you know, that’s the world that I was born into. First of all, I was born in 1984; the last album that my dad bought (before he had children and essentially stopped buying albums) was Run-DMC’s first album. I was born and raised in the hip-hop era. I lost my virginity in the early 2000s, well after the heyday of rock and roll. We were born in an era that’s about using references to communicate emotions, and it’s kind of a myth to pretend that it was ever any different. Like, people try to say the Beatles are somehow the greatest example of this golden age of rock music—that’s when it becomes a true art form, right? All their music is references! We just don’t understand them as well. Some people listen to Sgt. Pepper and are like, “Wow, these guys are just pure geniuses, just pulling ideas out of thin air.” It’s bullshit because it’s basically a hip-hop album full of samples, in a sense.

BLVR: The White Album, especially.

EK: Oh, yeah, The White Album even more, but even the title Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, like they’re referencing Victorian shit, the old music their parents listened to, British dancehall music.

BLVR: The cover is all references.

EK: To me all good art is, to some extent, a game of references. Like, I always had this issue when I was growing up and getting taught about poetry. There was this weird idea that if you looked into your heart, then you would find truth. And when they teach you about writing poems, it’s like, “Express yourself.” It would have been much better advice to just straight-up say, “Copy shit you think is cool, write about the things that you think are cool, and through that process you will one day… express yourself.” This idea that inside of you is the truth and that the world around you is bullshit? That’s bullshit. Inside of you is bullshit; the world is full of truth.

BLVR: Inside of you is bullshit?

EK: Yeah, for most people. We were born and raised in a wicked world, so there is an element of original sin that, merely by being born in 1984 in New York City, I was born into a wicked world and therefore there is an element of wickedness. You’re not born neutral. You know You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train? Howard Zinn? You can’t be neutral when you’re born into a wicked world, so if you think that you’re born with the truth inside of you—that’s not true. You’re born with bullshit inside of you. Even the fact that you were born is probably not a good idea—born into an overpopulated, unequal, miserable world—so I think it’s much better to look around you, look at the wisdom of people who came before you, look at the experiences and ideas of your fellow humans.

BLVR: OK, but with everything you’re talking about, growing up in the age of hip-hop, do you think that being in a rock band is still something that can matter?

EK: Well, here is what I think: we are still very much in the age of hip-hop. Hip-hop today feels like the early ’90s did for rock. The early ’90s, by most accounts, was an exciting time for guitars. Rock still felt vibrant. It was kind of the top of the world and reaching peaks that dwarfed the previous peaks. That’s basically how hip-hop feels now, especially in the last few years. I mean, if in my lifetime there comes a moment when rock-and-roll bands with electric guitars and drums become the dominant form of self-expression for young people in the English-speaking world, I will be shocked. I just don’t see that happening. But I’ve tried to rap many times in my life.

BLVR: When was that?

EK: I mean, I’ve been rapping as long as—see, this is why I knew it wasn’t a good idea to bring it up: because even when I talk about it, it sounds corny—but basically I’ve been rapping as long as I’ve been writing rock songs.

BLVR: Which is how long?

EK: I mean, I guess twenty-one years or something. Like, one of the first songs I wrote was on the piano and it was called “Bad Birthday Party,” and probably right around then I wrote my first rap, which was this terrible song called “The Landlord Rap” that was about a landlord saying, “It’s time for you to pay your rent.” [Laughs] I don’t even know why I was fixated on landlords. Throughout my life I’ve done different kinds of rap. One of the first cool, older kids I met in high school still releases rap music to this day under the name Lushlife—he took me under his wing and we would rap and freestyle battle. And even in college I was starting a kind of a rap group but I guess I never found a voice. As much as I love rap and I love writing rap lyrics, I never found a voice as a rapper that I felt as comfortable in as the voice I found as a singer in a band. It wasn’t in the cards for me to be a rapper, as much as I tried, and, you know, it didn’t leave my life devoid of meaning. I didn’t kill myself, even after I had that realization. I decided that I would continue to live [laughs], and I realized that I could still make other types of music even though it’s the hip-hop era. So it’s all a matter of just knowing the context of the world that you’re putting your stuff out to. Some people will say context doesn’t matter, but I’m a context person.

BLVR: It seems like this is related to the issue of timelessness.

EK: Yeah, the way I think about it is: if in 1975, the middle of the rock-and-roll era, somebody decided to make an album that was a folk album, it wouldn’t be absurd, but you’d have to be very much aware that you’re making a folk album in the rock era. That’s all. You go ahead, you do your thing, you listen to Woody Guthrie or whatever, but you’re making a folk album in an era when everything is somehow contextualized by rock and roll. So when you make an album now, you can make a rock-and-roll album and it will be seen as a rock-and-roll album in a non-rock-and-roll era and you can use that information how you wish. You can be contrarian and say, “I don’t give a fuck about Kanye or Drake. I hope this sounds like it was recorded on a cassette tape in 1988. I hope this sounds exactly like a Dinosaur Jr. album, because that’s interesting to me,” or you can say, “OK, I want there to be some interplay between what I’m doing and what the greatest artists in the world are doing at the same time.” Like you said: I posted a poem on my Twitter. That’s a pretty dated art form. Lots of kids are studying rap and pop lyrics for fun, and they tend not to do that with written poetry. But that doesn’t mean you can’t write a poem; you just gotta say, “I’m writing a poem in 2014.” That’s all you need to know. Some artists would say that context doesn’t really help them, but I can’t really imagine it any other way.