Frank Stella had come to Toronto to help promote an exhibition of his prints from the collection of a friend of his who owned the Adelaide Club, where the prints were being shown. The night of the opening my friend and I went and realized that the Adelaide Club was not, as we’d expected, a gentlemen’s club with bookshelves lining the walls, but rather a health club—a fitness center—and so among those who arrived in all their elegance to drink the free wine and eat the canapés and hear Frank Stella say a few words were men and women sweating through their spandex, passing among the hobnobbers with towels thrown over their shoulders, on their way to and from the locker rooms. It was bizarre.

The next day I met Mr. Stella in the Adelaide Club once again. It was eleven in the morning. All signs of the former night’s elegance were gone. The long white drapes that had obscured the squash courts were pulled back to reveal men in shorts and wristbands. On the counter where there had been white wine were now cups of yogurt and granola. We sat at a high table and Mr. Stella wore a fleece vest with TEAM STELLA embroidered in small letters above a pocket.

Frank Stella, born in 1936 in Malden, Massachusetts, has been considered a major American artist for almost fifty years, becoming, in 1970, the youngest artist ever to have a career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He is best known for the monochromatic pinstriped paintings that first brought him to prominence, which when seen in person have a very moving, vulnerable quality, and (a few years later) for his color-field paintings on irregularly shaped canvases. He helped legitimize printmaking as an artform in the late 1960s, and his work in the 1980s included paintings in high relief on objects such as freestanding metal pieces that contrasted with his early, minimalist works. He seems to be all over Toronto—a bright, mural-size work of intertwining half-circles from 1970, Damascus Gate, Stretch Variation, hangs high on a wall in the David Mirvish bookshop, where I first saw his work as a child. In the past twenty years, he has taken on architecturally scaled sculptural commissions, such as the design of the interior of the Princess of Wales Theatre here, as well as an installation in front of the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C.

Frank Stella spoke especially quickly during this interview, with much energy and an air of distraction. After it was done, while waiting for the elevator to go back up to the main floor of the mall, I noticed Mr. Stella leaning over a railing, looking at one of the paintings he had made in the 1980s, hanging high above a fleet of StairMaster machines below.

—Sheila Heti

*

I. HAPPY TO BE THERE

THE BELIEVER: There’s a fiction writer in Canada who’s fairly famous—her name is Barbara Gowdy. When I interviewed her a few years ago, she said that her first love was to be a concert pianist, and it was her theory that everyone does their second love, and that’s sort of our condition. I wonder for if you’re at all doing your second love or if painting is your first love.

FRANK STELLA: Certainly there weren’t any other arts that made much sense for me. Being tone-deaf, music certainly was not in the cards. My mother painted and there were paintings around the house, and I was interested in painting and I stayed interested in it, and I sort of, in a mild – actually fairly straightforward way – practiced it at the level I could at a young age. It’s not like with musicians, say, where there is exceptional technique and ability at a very young age. I was not exceptional, but I liked it and I worked at it and I was satisfied by what I was doing. I mean in terms of, things would occur to me and I was never finished. There was always something ahead of me.

BLVR: You say you weren’t exceptional in any way. Then how do you account for the place that you’ve reached in your career and art history and in relation to others painters of your generation, which is obviously pretty high?

FS: I work at it. As I say, I have no particular talent, but I have a familiarity and a lot of experience with the materiality of painting, since I’ve been doing it since I was 12 or 14. That counts for something. I have a lot of experience – way more experience than ability. I also know what I like and I’m not shy about making a judgement about what’s worth doing.

BLVR: Is it possible for someone to be a very great painter if they don’t have a lot of familiarity with paintings and art history?

FS: Yeah, I think that happened to me. I understood art from Manet to Pollock. I really knew what that art was about. I was pretty confident, and probably rightly so, about my take on what was called modern art, and it’s what I wanted to do, so I both studied it and was immersed in it. But I knew that I didn’t have much of a sense of the painting that came before, so around 1980 I got involved in writing a bit, and I started to look at the art of the past, but from the point of view of having made art myself, which was a slightly different way of looking at it. Then I found myself to be fairly comfortable in it and I was able to have an understanding of art back to the 13th century. I went to look at Austrian painting. I went to all the great museums, as they say.

BLVR: Did that bring about a new way of thinking about art for you – to be straightforwardly analytical?

FS: I don’t think it was so analytical. It was about seeing, and it was about seeing the real thing in the real place, either the museum or – I mean, the biggest turn-on for me was Caravaggio, not because I like Caravaggio so much, but because in Rome you could see the Caravaggios where they had been made – not where they were actually painted, but a few blocks away, and then they were moved into the churches. That’s a totally different kind of seeing.

BLVR: When you started out, you wanted your paintings to have total stability and total symmetrical organization. Then the work became more dynamic and was less about being totally stable, and I wonder if it seems to you that the need for total stability and total symmetrical organization are the needs of a young man.

FS: Yes, it could be. You like to have a structure. It’s not so bad to make something that you feel is strong enough to build on, so then you gain a certain confidence.

BLVR: When you look at that early work of yours now, does it seem like it doesn’t have emotion in it? The black paintings for example…

FS: Actually, it’s the opposite of that. The goal is a level of feeling beyond the normal feeling, which can be relatively trivial, so the search is for the absolute or the pure feeling.

BLVR: And do you feel like there’s a range of absolute and pure feelings, the same way that there’s a range of trivial feelings, or is there sort of one ur-pure-feeling?

FS: I wouldn’t dwell on them being trivial feelings. I would say normal feelings.

BLVR: Daily feelings, okay.

pause

BLVR: So do you think that in any way changes the human being – to have abstract art in our consciousness?

FS: Well, I don’t have a lot of faith in the efficacy of art in relation to living a life, but for some people I think it can be comforting. It can be uplifting. It can be a challenge. From the professional point of view, it’s the challenge that’s kind of great. But in the end, look, I’m part of an enterprise of painting, which is painting in my time, and I’m a very small part of that. And if you take the totality of it, the organism of visual culture or art, which is kind of evolutionary, I’m an infinitesimal part of that, but I’m happy to be there.

II. JUNK IN A COHERENT FORM

BLVR: You wrote an essay in which you said that there are certain things you don’t consider art. You don’t consider performance art art, you don’t consider photography art, you don’t consider –

FS: Yeah, I got on a tear one time.

BLVR: – video art isn’t art…

FS: There are a lot of things I don’t like.

BLVR: Do you actually consider that work not art?

FS: Well it’s, I don’t know, it’s a tawdry kind of art. It’s art that hangs onto the kind of art I consider really worth doing. But look, I would love performance art if they had their own performance art museums. There should be photography museums. There should be video art museums. I don’t need to go to a museum that has painting and great art in it to look at videos. They should have their own place.

BLVR: So you want to segregate?

FS: I think they should be separate but equal, yes.

BLVR: Yet you’re obviously interested in architecture. Do you consider that art? Richard Serra said it’s absolutely not, because if you have to worry about plumbing, it’s not an art.

FS: Yeah, well Richard has a limited view of a lot of things, but you know, there’s a tradition, at least since more or less the Renaissance, of the fine arts being painting, sculpture and architecture. And that’s quite broad, and I like to stick with that very broad definition. Of course, in actuality, there was a lot of performance art during Renaissance. They painted on the front of buildings and they did all the painting for the parades and marches and everything. It wouldn’t be what’s in museums now, largely because it’s ephemeral and didn’t survive. So perhaps it’s not quite right to say what I said, but that’s the way I felt about it when I wrote about it. I was getting tired. I didn’t like the museums being overrun with just a lot of junk! I mean, I’ve produced plenty of junk myself, but in a more coherent form.

BLVR: I interviewed the art critic Dave Hickey a while ago, and he said the important thing was to want to win – you have to want to win. Do you agree?

FS: No. Like I said, you’re a small part of the enterprise and an infinitesimal part of the organism, and you don’t win anything. You’re just lucky to be conscious for a limited amount of time, and what you’re able to do with your consciousness is up to you. You don’t win anything. There’s nothing to win.

BLVR: Do you feel like you have any personal stake in abstraction continuing in any direction? In any essay you wrote, you said that the values of materialism should inform abstract art rather than the values of spiritualism.

FS: Well, I never was very big on the spiritual aspect. I’m interested in the final – the concrete expression of those feelings. Abstract art continues to get made and to my mind it’s usually the better art, so I’m happy with that.

III. DONALD DUCK AND NAKED WOMEN

BLVR: You once said that you only have enough time to be a painter – you don’t have enough time to be an artist. What does that look like to you – an artist?

FS: Artists are worried about their career and being artists and looking like artists, I guess. I only worry about what I do, I don’t worry too much about how I’m perceived as a person. I worry a little bit about the perception of my work, but not about what people think about me.

BLVR: And what about the perception of your work do you worry about?

FS: Well, I don’t worry that much about it. Usually the negative criticism is what you hear most of, but it pretty much evens out. If you were to go through all the criticism – which I don’t recommend to anybody – the praise is more or less equal to the criticism or the negativism, so the positive balances the negative. I mean, it’s pretty much a push or I wouldn’t be here doing this interview if the negative things overwhelmed everything. I probably wouldn’t be around.

BLVR: Do you feel like it’s taken away from your life at all to be an artist, or only given you things?

FS: It’s not much of a judgement for me to make. I don’t know anything else and I really can’t actually imagine anything else.

BLVR: You’ve had two children, right?

FS: Actually I’ve had five children.

BLVR: Oh, five children. And –

FS: That creates a life of its own, so you don’t have to worry. I mean, I don’t have extra time on my hands.

BLVR: Were you really engaged with child-rearing?

FS: Well, yes, I mean – yes. I – you know – I didn’t do a very good job, but I was plenty engaged.

BLVR: And you were married to the critic Barbara Rose, I guess, for a while –

FS: Yes, yes.

BLVR: I’m a fiction writer, and well, it sounds ridiculous to say that I’m no longer married but it’s true, and I was also married to a critic, and I just wanted to know whether you had any thoughts on an artist being married to a critic. Is there a weird –

FS: Well, I’ll put it as straight as I can. Barbara was a better critic when she was married to me than she ever was after.

BLVR: What does that mean?

FS: You can think what you want to.

BLVR: Was it based on the conversations that you guys would have together or was it simply –

FS: I don’t make a judgment; I’m just pointing to the facts.

BLVR: You once said, “I do not have a secret desire to put Donald Duck or naked women in my paintings, although I know they harbour a secret desire to be there.”

FS: Yeah, I think that it’s true. (laughs) Naked women always want to get into paintings. They always want to take off their clothes. They always want to be photographed. That’s a fact. And Donald Duck is pretty aggressive in that way, too.

BLVR: Of all the Disney characters.

FS: Well, I could have chosen another but I like Donald Duck and naked women. They went together. That was a literary conceit.

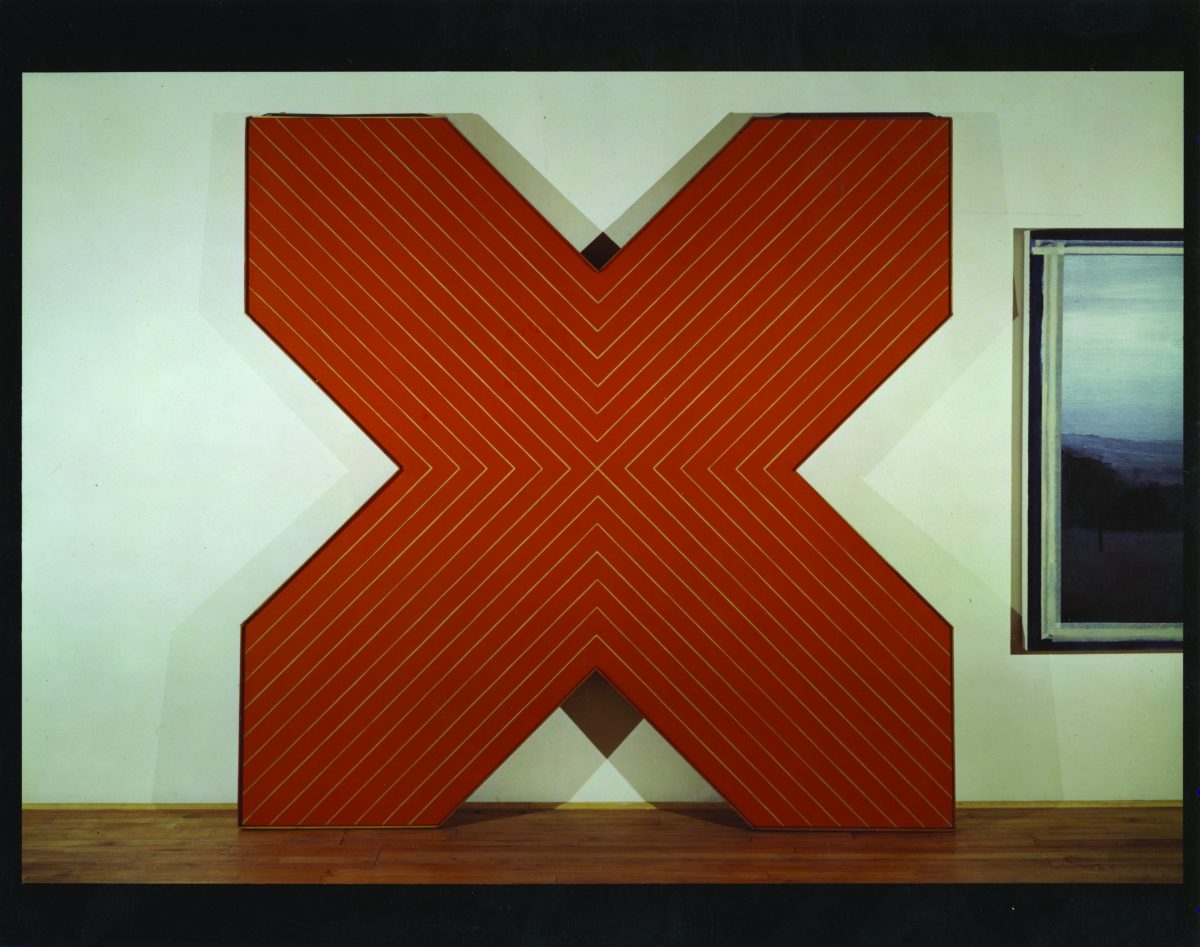

Frank Stella, Tampa, 1963. Red lead on canvas. 8′ 3 3⁄8″ x 8′ 3 3⁄8″. Private Collection. Courtesy Art Resource, New York.

IV. LEO CASTELLI’S NEIGHBOURHOOD BODEGA

BLVR: Do you miss that time in American art, the fifties and so on, looking at the art world now, the kind of things people are doing –

FS: Well, it’s pretty amorphous now, and there are artists that I like – and don’t ask me who they are because I keep forgetting the names – but I know the work and everything, and there are quite a few. I see things that I like quite a lot all the time, but I don’t get much of a sense of relatedness or coherence, and I see the other stuff around it as being not so interesting – you know, very average kind of landscape painting and this semi-pseudo porn. It seems like a waste of time to me. But look, I don’t really care actually. It’s not relevant to what I do or how I live.

BLVR: Do you buy that old Arthur Danto formulation about the end of art and that basically the movement of art has stopped happening and it’s just going to be this pluralism for good?

FS: It’s not a bad idea but I doubt that because I assume that the better work will coalesce eventually – or at least how we see it – so it will look like there was something serious going on and that there was coherence. It’s pretty hard to believe that now, but I don’t know that it was ever that true before.

BLVR: You don’t think?

FS: No.

BLVR: You think it was just put together by the critics –

FS: Yeah, it was kind of exaggerated. Take cubism – okay. Braque, then Picasso really got into it. So okay, two guys were doing it. Then four or five years later, there was Juan Gris. A lot of people got into cubism, and it showed up in Mondrian, Malevich – it showed up in a lot of people and in a lot of other places, but it wasn’t a real movement. It was people using the ideas of the people who generated the original ideas, making them essentially more diffuse, although some of them had good consequences. So I think there’s always a diffuse quality to movements.

BLVR: So you think there are people who have an original way of doing things, and then there are copiers, and they lift –

FS: Well, that’s a brutal way of putting it, but some artists have great – a greater degree or a more significant profile or originality than others. You can’t deny that. Art historians, if they’re being complimentary, they’ll say, This work was without precedent. That pretty much tells the story.

BLVR: I might be mistaken, but did you once say that an artist whose art does not resemble them is to be trusted?

FS: I don’t think that’s my way of thinking, no. I’d be more interested in the other. The more it resembles them the less interesting it sounds to me. (laughs) I’m all in favour of the shifty artist.

BLVR: I know you speak a lot about “quality” and quality in art – do you think it’s just as legitimate to devote your life to quality in some other area, other than art? Like a really quality pizza shop or being a really quality teacher?

FS: Yeah, you know, nobody wants to fly on an airline that’s 85% successful at landing their planes. So one of the things about art is – I think it’s a problem – that you can’t train an artist anymore. There was an assumption before – with the academies – that you could get a trainable result, and that would result in quality, but that hasn’t been the case in a long time. Art actually doesn’t have a style of education, although we continue to have art schools. All my teachers told me, Don’t go to art school. That was their absolute advice.

BLVR: What do you mean, anymore? Do you think there was a time one could train artists?

FS: Well, certainly in the 17th century we had academic training, and there was the apprentice system in the Renaissance – people did learn certain techniques. But we don’t have that now. With the rise of abstraction and the demise of mimetic art, when you’re not trying to make an image that represents something so someone can tell what that image is supposed to be, what kind of technique do you need? I mean, you need technique to make the image arresting or something you could care about, but you can pretty much do that any way you want to.

BLVR: Were you a good draughtsman?

FS: No, not at all. I never was – I never studied art conventionally.

BLVR: Is that weird to you? Does that ever feel awkward?

FS: Uh, no. I was born in 1936, so by then abstraction was established, so I studied that. (laughs) I wasn’t a bad student either.

BLVR: Is that when you got your teeth knocked out at school? In a lot of those early pictures, you don’t have front teeth.

FS: That was in the fifties.

BLVR: I think that would be kind of neat, to wander around university without any front teeth.

FS: I had a plate in university but I had bone in there. It was kind of botched; it wasn’t about being neat or having an image. It was about imperfect dentistry.

BLVR: So they didn’t do it well?

FS: Well, I had the plates but they always hurt because it came out about six years later – a piece of bone in the top.

BLVR: Speaking of Picasso and Braque, and I wonder if there’s been any friendships like that in your life, art friendships that particularly –

FS: Well, I don’t know how friendly they were when Picasso ran wild over Braque’s ideas. (laughs) I was friendly with artists and I still am friendly. It was small and it was quiet in the 60s. I was very active, and it was active – not really quiet, but it was small, so the artists, we saw each other a lot, and Leo’s gallery was sort of like – I don’t know; galleries now are so business-oriented and whatever, and Leo’s gallery was sort of like a mom and pop shop, a neighbourhood bodega.

BLVR: I have a painter friend from Shanghai, and he just had his first solo show in New York and he was really depressed because the day he arrived, the gallerist didn’t take him out for dinner, he had his assistant take him out for dinner because he had just bought a yacht and wanted to wash or touch his yacht.

FS: Well, there are infinite amounts of slights that we endure.

V. GAMBLING WITH LIFE VS GAMBLING

BLVR: You once wrote that “life is more wonderful than the imagination and recall of the people who life it,” and I wonder if to any extent making art is an engagement with art at its –

FS: Yeah, I think that’s what you feel when you see a great Ruebens or Velasquez or – that’s what a great painting does for you. It reminds you of that fact. Whatever they were, it’s gone, and their consciousness has evaporated, and something magical was achieved above it all.

BLVR: Are there some things you can now say for certain about art, that you know for certain about art?

FS: It’s just too tempting to say that you know that there’s no certainty. I mean, the way you frame the question that makes for a kind of inevitable answer. (laughs)

BLVR: Then are there things you’re more sure about than you were then?

FS: I mean, you have more experience. You make a lot of decisions based on experience, and you’re sure of them based on experience, but you know, you could be wrong. Also, your experience is fragmented. I mean, you tend to think of it as sort of systematic – you did this, you did that, you know this, you know that, but after a while it’s a mish-mash, so – a lot of artists say it, and a lot of people say it about everything, but in the end you have to temper your experience with intuition – in the moment. That’s why I like racing. They have to do it in the moment, and they do it on the basis of how they think they’re going to stay alive. (laughs) But it’s a very quick decision.

BLVR: Do you like betting, gambling?

FS: No, actually. I gamble a little but my whole life is a gamble as they would say, so gambling doesn’t interest me. That’s a trivial level compared to what I expend on trying to make art. I mean, if I could temper that habit, probably I’d be a lot better off. Maybe I should go to Art Anonymous.

BLVR: I know you have a horse farm and that you like racing horses and so on, and in your talk last night you said that there’s no connection between art and sport. Do you really believe there’s no connection?

FS: Well, all activities generate their own sense of beauty and accomplishment, so I suppose in that sense they’re connected, but sports really is about winning, and art really isn’t. Art’s about being able to make something that’s beautiful. There are millions of really great sportsmen who really love the beauty of the game, but in the end they’re happy to win ugly. They say that all the time: If we have to, we’ll win ugly. But you can’t win ugly in painting. Though guys have tried.