Gus Van Sant’s twelve feature-length films are multicolored magnifiers of disquiet, loveable investigations into death. His twenty-three-year career, which also includes a novel, music videos, a book of photography, a couple of CDs, and a slew of short films, falls into roughly three periods:

The early features—Drugstore Cowboy, My Own Private Idaho, and the recently rereleased Mala Noche—are gritty, lyrical portraits of small-time junkies and vagrants, heading for futile, youthful deaths.

The mid ’90s brought a string of more commercial films—Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, Good Will Hunting, To Die For, and the shot-for-shot remake of Psycho. Made with bigger budgets and name-brand actors, they, in turn, led to Oscars and name recognition. In that period he tried his hand at writing a novel, Pink, often thought of as an exploration of the death of River Phoenix.

Then came Gerry, a film of long, real-time takes, marking Van Sant’s return, with extraordinary force and clarity, to the subject of mortality. Matt Damon and Casey Affleck wander for a hundred minutes through the desert, in brute desolation, barely talking, before one dies. Here, the mundane and silent become metaphysical. Everyday details reconstruct the moments leading up to death, an exploration Van Sant continues in his most recent films, Elephant, Last Days, and now Paranoid Park, a set of elegies of extraordinary compassion.

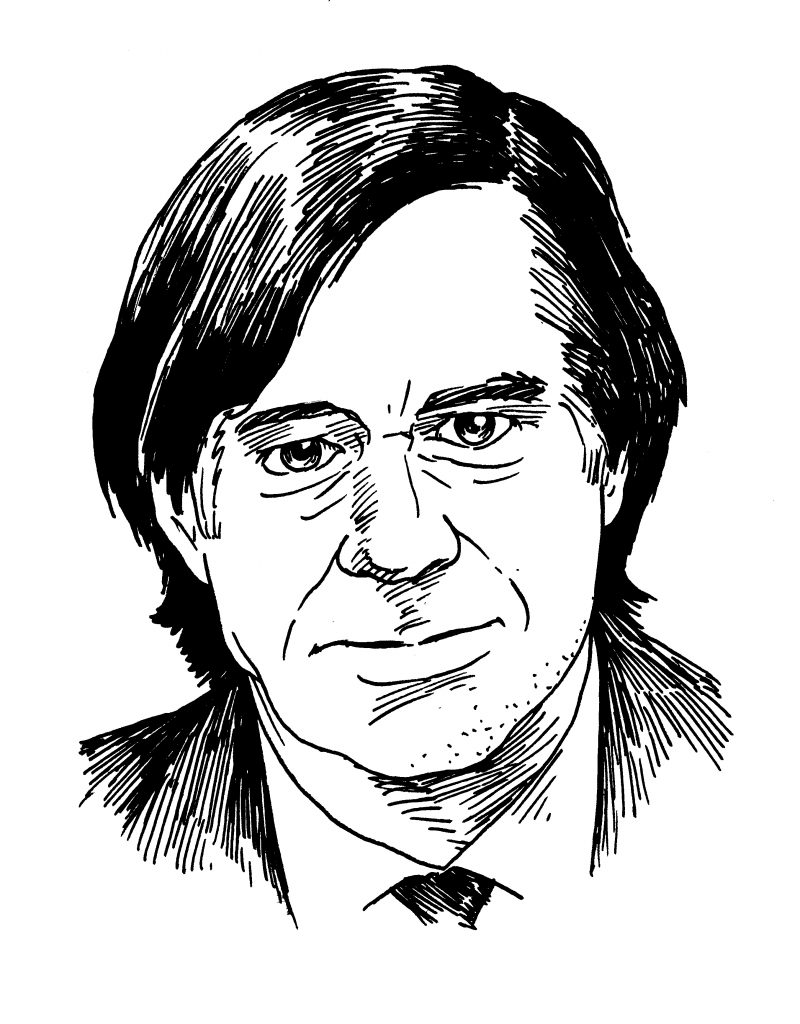

On the occasion of this interview, Van Sant was attending the North American premiere of Paranoid Park at the Toronto International Film Festival. Compact and orderly, he appeared promptly for the interview at the Four Seasons Hotel Café, where he discussed his career and ate Belgian waffles.

—Alexandra Rockingham

I. FRANK’S THE GUY TO TALK TO

THE BELIEVER: You went through a very interesting period in the late ’90s. You made two commercial projects, Good Will Hunting and Finding Forrester. You wrote a novel. And you remade Psycho shot for shot. To copy a film shot for shot, it seems to me an artist must either be having us all on, or be in a very dire place, or maybe both. But it really seems you were trying to get back to some understanding of the fundamental language of your medium. Is that in any way how you feel about that period now?

GUS VAN SANT: Sometimes I see a script and I just like it for one reason or another. Sometimes I’m doing things partially because I haven’t done them. When it came to Good Will Hunting, I guess I just had never made a film with a hero. They had always been antiheros, and I thought, Well, let’s just see if I can. And then, because of the way Good Will Hunting played—it did very well in the marketplace and Miramax got it nominated for a bunch of awards—it was the first time it happened where a studio was interested in making a deal with me, and they would let me do anything I wanted, and they would pay me more money than I’d ever made. So, there were some projects I never really could get going, and one of them was Psycho. It was a project that I suggested earlier in the ’90s. It was the first time that I was able to actually do what I suggested. And the reason that I suggested Psycho to them was partly the artistic appropriation side, but it was also partly because I had been in the business long enough that I was aware of certain executive’s desires. The most interesting films that studios want to be making are sequels. They would rather make sequels than make the originals, which is always a kind of a funny Catch-22. They have to make Bourne Identity before they make Bourne Ultimatum. They don’t really want to make Bourne Identity because it’s a trial thing. But they really want to make Bourne Ultimatum. So it was an idea I had—you know, why don’t you guys just start remaking your hits. It came after Drugstore Cowboy. I was in the office of the president of Universal and he had with him a lot of other executives, and one of the executives was in charge of the library. So they looked at me and said, this is Frank, he’s in charge of the library, and if there are any old films that you might want to remake, Frank’s the guy to talk to. What they meant was—which was just an accepted meaning—any old films that people don’t know about, you can rob them, or take them and popularize them. So earlier, when I was in a screening for Drugstore Cowboy, I kind of flippantly said—and also, I was young and I was sort of angry about the way executives would think about films—I said, why don’t you guys go for the gusto, remake your hits and try and get those to sell, because those were the ones that were the hits. Don’t remake the obscure detective movie that nobody knows about.

BLVR: Seems quite logical.

GVS: There were other things going on at that same time. Remaking TV shows into movies—like The Addams Family was the first one. What they really needed was brand identity. So when someone goes to see a movie, they go to see The Brady Bunch, they know what it is because they watched the TV show. It’s sort of similar to remaking a hit. I just chose Psycho out of the blue. I just knew it was a Universal film and it was a hit at the time. I said, remake a movie you like—Psycho, for instance—and don’t change anything. Just copy it. Make it color, and have your new cast, have Jack Nicholson play the detective, recast it with modern people, update it. But leave the technical side the same—it seems to work, so why play with it? And they just sort of laughed and said, well, we won’t be doing that. But later, every time I went back to Universal I would say the same thing. And they would just laugh. And then came the winter of 1998, the day before the Academy Awards, and Good Will Hunting was up for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Screenplay—nine categories. The day before, the awards agents and executives go crazy. They have six or seven films that are big possible winners, and over the phone—you don’t even have to have a meeting at that point—over the phone they’re trying to make a deal with you, through your through your agent, which they can probably cancel if they want. So my agent says, “Universal is calling. They just want to do something, what’s your dream project? Anything you want to do.” And I said, “Oh, I know, tell him Psycho. Don’t change anything. Just copy the film, make it in color with a new cast.” And five minutes later he calls back and says, they think that’s a great idea. So even though it wasn’t such a good idea before, now, because Good Will Hunting is doing well, it’s a great idea.

II. “THERE IS NO LINE.”

BLVR: After Psycho and the commercial films, Gerry comes along. And it’s the first step toward this trilogy. I see a progression: First Psycho, then Gerry, and then the trilogy of Elephant, Last Days, and now Paranoid Park. By the time you made Gerry, you had become interested in the long take and real-time tradition of the 1970s— the Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman, or the work of Andrei Tarkovsky, of Warhol earlier than that, and the Hungarian master Béla Tarr, who’s still making films. With Gerry you set up the simplest thing a filmmaker can do: people in a desert, in a bare landscape. And you seem to just set the camera down in the dust and let the people move through the frame. So although it is derived straight from that 1970s movement, it’s also like the first small step toward finding a new language.

GVS: Yeah, I think a lot of it had to do with what you’re saying, the language, and then watching Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó.

BLVR: His eight-hour film set in post-communist Hungary. It rains and rains and villagers trudge through mud, all in very long, real-time takes. That’s how I remember it. Nothing much happens, but a very beautiful film.

GVS: It was like, wow, here’s an example of a different language. Experimental cinema was where I had come from. I was a painter early on, that was sort of what I did. In high school you don’t really have an identity, but I think as much as you could, I was a painter in high school. I also did stuff with film, but it was pretty much experimental cinema. I went into New York City to watch Anthology Film Archives shorts, and when I went to Providence [at the Rhode Island School of Design] we were watching experimental shorts. Michael Snow would come to speak and show his films. Wavelength was one of them. We were interested in expanded cinema and the avant-garde. Going to L.A. eventually, and working in the system, you always have that in your head, that cinema. Modern cinema is a code, and it was created somewhere along the line. The standards that you’re learning—and I guess this is true with other mediums—but the standards are created and absorbed and re-created. Abstract art is sort of an invention that is absorbed and becomes its own idiom—I was interested in that version for a popular cinema. I was also reading Marshall McLuhan. His main thing is “the medium is the message,” and it sort of becomes obvious that modern cinema is just using film to present something that really was from other media, like literature or stage plays. It wasn’t yet actually its own thing, and it was subverted in some ways by the invention of the close-up and medium shot in the mid-teens, 1910 to 1920. They were stylistic innovations, but they became the popular idiom. And it is also the way you tell the story—it’s coming from previous media. The thing that Marshall McLuhan is criticizing or observing: that the new medium will borrow from the old medium until it becomes its own. Writing will be used just to copy down words until it actually arrives at its own thought process and becomes the novel, which isn’t just copying down an orator’s words, it eventually works like psychological storytelling. So film is borrowing from previous media until it can arrive at whatever it is supposed to arrive at. Watching Sátántangó, I was thinking, Wow, this is the guy who’s beat the system. One little rule about shooting is that you’re not supposed to cross the line between two characters. You shoot on one side of the line—you can’t just pop to the other side of the line, because what a camera seems to be doing is just mimicking a person in the room. It becomes a person in the room, an observer. So I was always interested in this one little question, which was, How do you cross the line? And then watching Béla’s film I thought, Oh, I see, the way to cross the line is to not have a line, of course. He was thinking outside the box. There is no line. The camera doesn’t cut back and forth. And I thought, Ah, it’s so brilliant, because why should you create a line? Why should you have cutting back and forth? That’s not like an observer. Eyes do dart back and forth, as if we’re cutting. Our eyes fl it from one shot to another—cutting is mimicking that—but ultimately it’s not really a cut, it’s a really fast whip pan.

BLVR: No shortage of whip pans in movies these days. Any car chase or fight scene in a Bourne film seems made up mostly of whip pans.

GVS: It was a way to create a new language. Maybe it’s not getting out of the literary, because the literary thing that Marshall McLuhan is talking about is really, really hard to break. It’s not an easy thing to just go, Ah, we’re not going to copy plays and literature, we’re just going to do our own thing. And the true experimental filmmakers, like Kenneth Anger or Stan Brakage, they’re really doing that, they’re breaking the role, they’re getting out of the literature model, they’re creating a new cinema. But it doesn’t become absorbed by the popular consumer or observer.

III. CINEMATIC TRUTH

BLVR: I love the way your newer films create a personal world inside the viewer. And I think the longer takes are part of that, or at least it seems that the long takes are the means by which you started to discover how to do that.

GVS: I think that they are sort of stylistically innovative films, but they’re not really breaking out of a literary model. They are sort of going more into the literary model. Or at least my observation is that they’re actually becoming more like something that would be in a novel. Because of the spaces within them, there’s a lot of time that goes by. If somebody in Elephant walks down the hallway for three minutes, to me, it is novelistic in the sense that a writer might describe somebody walking down a hallway for three pages. They might take a number of pages just to describe a very simple thing. I mean, there’s a short story by David Foster Wallace where he describes a man on a chaise lounge in the backyard. It takes ten pages or something like that, and you’re very riveted. You’re really following it.

BLVR: In that time you give us, we can do a kind of work, and fill in details. We see small things, the color of the walls, a shrug, the texture of the floor, the other kids looking over their shoulders, their different expressions.

GVS: So the films are attempting to head in a direction outside of the model, but it’s such a big impasse that it doesn’t just happen. My guess is that something else will happen before film can achieve its own language. Something like a three-dimensional environment will happen first. And I assume that will borrow from the previous media before it has its own life. And film will become antique, like silent film. There will be a new type of environmental cinema. It’ll be like cinema, but it won’t be flat on the wall.

BLVR: One thing about your films that I find incredibly important is their compassion. I distinguish this compassion from the effect of more typical Hollywood, where we are forced to relate sentimentally to a character. Sentimental, conventional films depend on preexisting emotional conditioning in us. They don’t show us anything new, they just show us a pattern that triggers a patterned response. What you seem to be seeking is a deeper compassion, which allows us to form our own unique emotional relationship with the character or story.

GVS: I get upset with a lot of films because if you’re interested in a character, there is no way that you can really see them—they’re always cutting away from them, even if it’s Brad Pitt or Meryl Streep. They’re doing really intense work and if you really want to see what they’re doing, you’ve only got three seconds, and then it’s off, and then you’re back, and then you’re off again. So I think partly it is just sitting there watching them for a pretty long time. It does what I liked in Béla’s stuff, or in other films that I’ve seen, like Chantal Akerman. You really get to watch the thing, like you might if you were really there. You have time to really be with the moment, rather than having a shorthand. In Gerry, you’re really walking across the desert with them, rather than showing them start and then finish their walk. You go through the actual walking part. In Elephant, there wasn’t a traditional script. There was no script. What we first did was have a group casting where we met the characters that ended up in the movie. And we kind of selected them and paired them down so that slowly we built a group of ten characters who we liked that were examples of different kids in high school—the librarian girl, the boy with dyed-blond hair, the tall photographer, the two killers. We had a core of kids. Mali Finn was the casting director, and she just talked to them. She was able to talk to them in this really intense way, where it was like psychotherapy almost. They would be telling stories about really intense things in their lives within a minute of talking to Mali, just by the way she conducted her interviews. So we said, OK, those are the characters, now we have to figure out what are we going to do with the characters. So I wrote up the script around the characters. I used some of their true life, like Elias really was a photographer, and things that I knew from my own high school experience. So you’re kind of docudramaing something that is built with characters. And then there are the long pieces of film, the time the viewer is spending with them added into that. Verisimilitude is forced on you. I just saw Jesse James [The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford]. It’s relaxed and nothing really is going on. But the characters are talking, they’re in the woods and you think, Ah, I really like to be here with these characters. And I was thinking, Why, exactly? You can’t tell what it is. Same with if you’re reading the first pages of a book and you’re really drawn in. It could be an easy description of a river, and you’re not sure why you’re happy to be there on page three, but you are. So even the novelist wouldn’t exactly be able to say how he’s doing it, except that he’s done it a lot. You sort of arrive at this ease with what you’re doing. Which is what the audience really likes. It has to do with having done it a lot. It’s not really about rules, it’s more like a sensation. I could write about a river for three pages and by the third page you would be going, All right, we get it. But somebody else, Nabokov, could write about a river for three pages and on page three you’re wanting more. I think it has to do with experience and the familiarity [an artist has] with his own style.

BLVR: I think it’s in your novel, Pink, where Todd Truelove, an experimental German filmmaker, disses cinéma vérité, and says that what he wants to do is to control the image in a way that allows the filmmaker to get at a more revelatory and transmissible truth.

GVS: It was something that I heard Werner Herzog say at our museum in Portland. He was showing a film. He’s really a great speaker, and a really great original thinker, as we know. He was speaking about cinematic truth, which often is discussed by filmmakers in very different ways. And I guess there was some kind of comment that he needed to make about cinéma vérité, which was a 1960s French movement of sorts. I guess the idea of cinéma vérité is that you just shoot and you don’t manipulate. You basically don’t cut the camera, you don’t turn it off, you keep shooting, and it sees truth because it’s not manipulated, it’s not cutting to close-ups, and it’s not cutting to other things because that would be an untruth, because cutting is an untruth. And Herzog is doing these fantastic, almost surreal presentations of all kinds of things, and he is shooting, at times, documentary subjects and he is manipulating in a non–cinéma vérité style. He went into this thing about how cinéma vérité was an insignificant moment in film history. It tells the truth about absolutely nothing. And I don’t know whether I agree with him, but I really do think that his cinema is unbelievably powerful, and he’s trying to get at the transmissible truth. And I think he does.

BLVR: Do you concern yourself with trying to get at truths?

GVS: Yeah, sure, I think about it. Certainly those three films [Elephant, Last Days, and Paranoid Park] are trying to get at some kind of truth that you didn’t see in other investigations. In Last Days I think that there was always this mystery about where [Kurt Cobain] went in this missing period, as if that were somehow an answer to why he was found dead. And I thought maybe it wasn’t really an answer, maybe it was just part of his life. And it was possibly very, very mundane and ordinary, and he might have just wandered around his house. Perhaps it’s not absolute, but perhaps this is the truth to the missing period of time, which I thought was an important and interesting mystery. And there were little hints as to what actually did happen. There were little moments where people saw Kurt. They were like these little pinpoints where you could kind of fill in the blanks. And I was trying to get at the truth of those three days—but the truth of just the mundanity, really. Whereas in Elephant there are way more truths that aren’t actually being stated, they are just sort of being brought up. The first one being the absence of the parent, the responsibility of the parent being abused. And then the next one is the environment of the high school, the absence of a system, the system being too small to actually control the kids. And the usual suspects lightly drifting through the frame that ignite your own thoughts about the subject, that gain momentum as you have time to think about it yourself, and add in your own reasoning. So by the end of the movie you’ve thought about it yourself, using your own information, without me saying what the truth of the matter is. There isn’t a hypothesis being spread out. It doesn’t lay out the answer, because laying out an answer, or even five or six answers, always leaves out the hundred other answers that are there, that can be supplied by us, by the audience, by one audience member at a time.