Guy Nordenson recommends that New York City embrace climate change and start anticipating its consequences. Earlier this year he presented the American Institute of Architects with findings from a two-year research project that envisions how rising sea levels will impact the city. The problem facing New York is not higher sea levels alone, though these may be more than forty-eight inches higher at century’s end. What concerns Nordenson are the severe storms and hurricanes that will become more frequent and more powerful on elevated, warmer oceans. On the Water/Palisade Bay, the book-length report produced by Nordenson’s team, includes an “Atlas of Edge Conditions” that shows in high resolution how far the surging floods delivered by these storms could reach.

Yet Nordenson is optimistic. In the aftermath of 9/11, he led a volunteer effort to triage four hundred buildings impacted by the World Trade Center’s collapse. It has also been his fortune to work with some of the best minds of two generations. His first job out of MIT was a drafting gig at the Long Island City studio shared by Isamu Noguchi, Buckminster Fuller, and Shoji Sadao. Nordenson has since served as a structural engineer on many of the projects that will define the architecture of this decade: the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Addition, in Kansas City, Missouri; the New Museum of Contemporary Art, in New York; and the Linked Hybrid Building, in Beijing. He is also a professor of architecture and structural engineering at Princeton University, the coauthor of Tall Buildings, the editor of Seven Structural Engineers: The Felix Candela Lectures, and is credited with the design of the torqued and tapered World Trade Center Tower One that preceded the numerous iterations of the so-called “Freedom Tower” by Daniel Libeskind and David Childs/SOM.

To reinvent New York City in an era of climate change, his Palisade Bay proposal calls for the renewal and expansion of wetlands as well as the introduction of piers, parks, and tidal marshes, ensuring a porous boundary between the city and the sea. Nordenson’s team of architects, engineers, and landscape architects also designed an archipelago of artificial islands and reefs. There are tidal turbines, wind farms, algae farms, and oyster beds. Unique conditions in each part of the city are engaged, Nordenson says, which allows for a genuine sense of place to emerge. Since its debut last May, he and his collaborators have presented the design to several audiences, including a few government agencies, heralding Palisade Bay as the Central Park of the twenty-first century. On the Water/Palisade Bay is the focus of a two-part exhibit this winter at The Museum of Modern Art and PS1 Contemporary Art Center in New York City.

—Scott Geiger

I. “A VERY OPEN KIND OF URBAN GESTURE”

THE BELIEVER: Your introductory essay for Tall Buildings describes the Statue of Liberty—a collaboration between a French sculptor, a French engineer, and an American architect—as “a speech act in the marketplace of urban ideas.” What do you mean by “speech act”?

GUY NORDENSON: It’s referring to a performative quality to the work as, in this case, the manifestation of the group effort and the international effort that led to the creation and placement of the Statue of Liberty. Historically, the Statue of Liberty came about because the French were trying to make a point within the context of their own political situation about democracy and saw an opportunity by making a gift to the United States to make a point back home. So they were exercising a speech act in the political realm in that sense. The relationship between the sculpture and the engineering was tricky because at some level [Gustave] Eiffel (the engineer) wasn’t particularly excited about working on something that would be hidden behind a dress. So he grumbled about it in his writing, but at the same time did something very inventive by taking a bridge pylon and turning it into the core of a tall structure with a curtain around it, inadvertently creating a paradigm for a certain kind of tall structure.

BLVR: How many projects have you worked on in China, built or unbuilt?

GN: Three.

BLVR: One of them is Steven Holl’s Linked Hybrid Building, in Beijing. If the Statue of Liberty is a speech act in the grammar of democratic capitalism, what is a speech act in the grammar of autocratic capitalism?

GN: Good question. The exciting thing for me was Steven’s determination that the building be public. That it not be separated from the city. Also, this fairly crazy idea of linking the buildings together at a higher level being completely the consequence of Steven’s will and determination, because the client still hasn’t quite figured out what to do with this.

BLVR: How big are the bridges?

GN: The bridges are at least fifteen or twenty feet wide. They’re big. They’re spaces. And they’ve been theoretically programmed as different. One is a swimming pool. Others are cafés or yoga exercise spaces. It’s fairly eclectic. But what they do is put you up in the middle of the city and move you between these buildings in this trajectory that starts high and slowly moves down low, so you’re not just going around but around and down, which is a really exhilarating perspective on the buildings themselves and also on the city around it, especially since you’re sitting at the corner of one of the ring roads. You have an amazing vantage point. I think in that sense it’s a very open kind of urban gesture. Ironically, when I went to visit the site last year, I had an opportunity to visit the CCTV Building while it was under construction, which is very striking and iconic but inside feels claustrophobic.

BLVR: China is said to be forward-looking. We have seen ambitious architecture and planning in the Persian Gulf for some time now. I wonder what you think of as “forward-looking”? Is there a tall building in China or elsewhere that exemplifies contemporary architecture and engineering?

GN: I think Rem Koolhaas is right that the tall building, as a type, is exhausted. The argument he made in favor of the CCTV Building had to do with the kind of social relationships he was trying to establish. The fact that in the end it doesn’t turn out as dynamic as you would expect I think undoubtedly has everything to do with the client, not with his ambitions. There’s opportunity in a loop to create different kinds of interactions. What Steven tries to do with the bridges—tying buildings together—those are things that take us into a different direction. There’s not a whole lot of that going on. Right now there’s every possible type of warped or oversize tall building going on in different parts of the world, but they are not that interesting. They’re baroque.

The one architect who has been consistently the most ambitious over time has been Norman Foster with the ways he has tried to think about the social organization of tall buildings, or “villages,” as he calls them, and the sustainability attempts that he has made.

BLVR: Foster was collaborating with Isamu Noguchi and Buckminster Fuller back in the 1970s, wasn’t he? Did you meet Foster during that period?

GN: I did not. But I did work on a project that was going on at the time, which I loved: the Samuel Beckett Theatre at Oxford. This was an early project of Foster’s that was not realized, an underground geodesic dome which was going to house this theater. We were working on it in the office, doing some drawings, and I was very excited because it had to do with Beckett.

BLVR: A buried theater for Beckett!

GN: I know. It’s bizarre.

BLVR: You’ve worked with a number of very accomplished architects. What are the parameters for a successful collaboration?

GN: There is a need to mark off territory so that inventive energies have space to develop. Where there is good collaboration, people are comfortable giving up space to each other because they believe that they will be pleased with what comes out of it. Look at someone like Peter Rice, a very successful Irish engineer who worked in France and Britain and collaborated very closely with Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers among others. He had a certain number of preoccupations. Piano and Rogers appreciated those preoccupations and benefited from them because they made their architecture more complex and sophisticated. They made room.

The opposite of that is Frank Gehry, where there is an absolute instrumentalization of all disciplines and all tools to execute an artistic vision with Gehry at the top of the pyramid. There are technical challenges and opportunities but not a whole lot of give and take. Frank Gehry’s relationship to engineering and construction says: the cruder the better. You visit the Disney Concert Hall and, in the office of the musical director, there’s this gigantic gusset plate that’s part of one of the trusses in the system. It’s exposed and fire-protected. One of the architects who worked on the project described it to me as a train crash in a room. It’s monumentally messy.

II. “A REFUGE THAT EVOLVED ON TOP OF A DUMP”

BLVR: Were you aware of architecture or engineering when you were young?

GN: I was aware of it. The main influence in that respect was through my mother’s friendship with Isamu Noguchi. This started well before I met him. But I heard storiesbefore that, in particular that he would point out Lever House as the most exquisite work of modern architecture.

BLVR: How was it that you ended up with Isamu Noguchi and Buckminster Fuller?

GN: While I was in college, my mother ran into Noguchi. At that point I was sort of trying to decide between different fields and was sort of interested in engineering. She talked to him about it and Noguchi said, “Oh, he should come and work for me and Bucky Fuller because we just bought this building together in Long Island City. Bucky would be a great inspiration for him.”

BLVR: There’s a Fuller exhibit making the rounds called Starting with the Universe. Some of his ideas—I’m thinking about the World Game and Spaceship Earth— offer a meaningful background to the energy crisis, the climate crisis, right?

GN: It’s interesting to ask: why Bucky now? I think it follows an anthology put out by Lars Müller called Your Private Sky. What that book did was to dig through the archive and highlight the side of Bucky that was the artist, his drawings in particular, the cartoon-like sketches of the 4D House and the ways in which a helicopter could install it. There was an energy in those drawings which I think surprises many people. The artist side as opposed to the intellectual side of Bucky is coming out.

BLVR: What comes out of On the Water/Palisade Bay is this vastly enlarged map of New York City that relates the metropolis to the regional ecology to ocean and weather. What were your sources? What maps and tools did your team create for the project?

GN: Historical documents about the evolution of the shoreline. Documents about the ecological history, about the oysters, for instance, from their discovery to their destruction because of sewage. We also learned about populations of birds and fish today to find out how they relate to the different regions of tidal flow. The modeling of the storm surge itself using computational fluiddynamic tools, ADCIRC, a tool for modeling surface water velocities. But also some other tools to create hurricanes and storm surges that were used in more local models. Various Google Earth maps, especially in threequarters perspective, through which we were able to create our approximate map of edge conditions. Where there are walls, we learned how tall they are, which we needed to compile so that we would have some basis to figure out if there was a flood, is the water stopped or does it have ways to get around.

BLVR: It’s been four hundred years since a ship captained by Henry Hudson, hired by the Dutch East India Company, arrived in these waters. To what extent is the design proposal for Palisade Bay a withdrawal or erasure of human presence?

GN: We’re trying not to approach this as a restoration. Instead, we’re trying to keep the spirit of Robert Smithson and others who looked at the postindustrial landscape, took it on its own terms, and tried to work from that. We’ve used Shooters Island, an island just west of the Bayonne Bridge, as an example. There was a shipbuilding facility on it. There are shipwrecks and buildings that are now submerged and used by all kinds of animals and wildlife. It’s a refuge, but it’s a refuge that evolved on top of a dump.

One of the discoveries of this whole project was, at the very beginning, the psychological aspect. Instead of considering climate change as only cataclysmic, we were looking to it as an opportunity and trying to find ways in which we could improve the urban environment. Implied in that is a sense that the ecology has to encompass what man has made. So, in a sense, it also means trying to chart terrain that is at some level in the subconscious and repressed. If you examine the bureaucratic structures built around preservation of ecological conditions, you see a lot of suppression of reality as well as protection.

BLVR: The term “soft infrastructure” is at the core of your book. Can you define it?

GN: By no means is it our invention. It’s a way to tie us to a larger perspective. If you look at the work of a lot of contemporary landscape architects, the movement called landscape urbanism, all of that has to do with the intermingling of infrastructure and landscape.

BLVR: So the water around New York City is potentially a secret park hidden in plain sight?

GN: The Upper Bay is the Central Park of the twenty-first century.

BLVR: Can you elaborate on the comparison though? Central Park, as conceived in the 1850s, was to be a geographical and social nexus for the city. It also communicated certain narratives about pastoral nature and city life. What do you think Palisade Bay will communicate? What messages are in the subtext?

GN: It links again to the psychological. Psychological is probably too weak a word. If you go back to D. H. Lawrence’s Studies in Classic American Literature, Lawrence recognized that in the nineteenth century there was this issue for Americans to contend at the same time with European culture and the wilderness. Both wilderness as reality and wilderness as an idea. I just finished reading a review of a biography of John Muir. Muir and Olmsted were part of a culture that included Melville and others who thought hard about what this wild animal of nature meant to them. The presence of Central Park in the city is tied to this thinking. Muir would have argued that, to be complete, humans must have that sense of both wonder and fear in the face of nature in the city as well as in the wild.

I grew up at a time when Central Park went through this transition from being a useful and functional part of our lives to a place that was to be feared. I think many people who lived in New York through the 1970s appreciated that there was this duality of danger and opportunity that existed in places like Central Park but also on the water, under the elevated highway, and out on the abandoned piers. This is what appealed to Smithson. He was another fan of Melville.

Where Palisade Bay has this kind of energy is where it comes between the apocalyptic tone of climate change and a very American tradition of thinking about nature.

BLVR: Palisade Bay doesn’t quite read to me as futurism. It includes artificial islands, wind farms, oyster beds, floating and detached piers of tall buildings. But there’s little sense that these elements are part of a distant future.

GN: For me, there’s a polemical advantage to making things seem as though they’re completely normal. For others, there’s a polemical advantage to making things seem utopian. I like the first, but it’s just personal disposition. And I’ve collaborated with people—Adam Yarinsky and Catherine Seavitt—who share the attitude that we should present things as if they are already here.

III. “I REFUSE TO CALL IT THE FREEDOM TOWER.”

BLVR: Things are quite bad for architects and engineers right now. But the collapse of the economy must have also opened up some opportunities, right?

GN: One is a reality-based approach to problem- solving. This means using whatever methods are available—peer review, competitions—to push in the direction of what actually works. There’s no need to throw tons of money at infrastructure, because there’s so much money that’s wasted in the way we do things now. In the early ’90s, I was working on a terminal at LaGuardia Airport, and at the same time there was a new airport being built outside of London called Stansted. There was an exquisite terminal being built there, designed by Norman Foster with Arup, the firm I was working with at the time. I learned that the cost of the terminals was the same but the quality at LaGuardia was abysmal. Banal design, cheap materials, et cetera. The administration of the project was corrupt. Waste was built into the system. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which was responsible for the terminal, had no mechanism to advance design excellence in any way.

BLVR: This begs the “Why can’t we have nice things in America?” question.

GN: It’s just method, not means. We have the resources. The most difficult thing to overcome in New York is the belief that mediocrity is inevitable. There are many examples of well-made buildings in New York, of inspiring architecture. We seem to do a pretty good job with microchips and iPhones. The fact that we don’t do as well with buildings is not because it can’t be done, it’s because for some reason we have this almost religious commitment to mediocrity.

BLVR: Do you see a line that connects your work in the post-9/11 building damage assessment and an interest in doing a project on the scale of Palisade Bay?

GN: Sure. Both show it’s true that groups of people and experts can self-organize at moments of crisis and work together effectively to solve complex real-time problems. I see an opposition between the sclerotic organisms that are operating in the domain of infrastructure in this country, both private and public, and the opportunities for democratic processes like what we accomplished for a while at Ground Zero and what this project represents.

BLVR: This chronology is really interesting. Where in your career does this project begin?

GN: There are a lot of interweaving threads, if you will, but a kind of nodal point for it all is 9/11. An organization I helped to found, the Structural Engineers Association of New York, through my own and other people’s initiatives got involved in providing volunteer expert opinion. We had two hundred members to mobilize. After getting that off the ground in the first couple of days, I ended up on the site, and I personally didn’t feel like there was a heck of a lot I could contribute standing around looking at all those cranes. There were a number of other people who were far better at looking at whether this crane could or couldn’t get up close to the slurry wall without collapsing the slurry wall. Bill Baker, for instance, the engineer of the Burj al-Dubai, jumped in a car in Chicago with three other guys, one of them being the engineer of the Sears Tower, and drove here. Better they than I. So, standing around, trying to figure out what I could contribute, I realized that no one was paying attention to the surrounding buildings.

I approached some of the people I knew in the buildings department and the Office of Emergency Management. My suggestion was: let’s go out there and systematically triage these buildings. To Giuliani’s credit, word went up the ladder, word came down the ladder: good idea. On the Monday afterward we had about eighty engineers and architects doing inspections based on the post-earthquake evaluation methodology developed in California. We also managed to get hold of a very highdefinition, current satellite photograph of the city, which I think a friend of mine in Albany managed to purloin from an NSA file. It was unbelievably high-resolution. So we had this on a CD that we gave everybody so they could look and zoom in on the roofs of all the buildings to see if there were any holes. There were four hundred buildings to consider and triage. The end result: 10 percent of the buildings were problematic, the rest were OK. But it was systematic. And this was the basis for whether people could go home or not go home. Then we would go back and look more closely at some of the buildings that were damaged and do floor-by-floor reports.

The process by which people were thinking through problems on the site was very striking. There were two shifts every day. One starting at eight in the morning, the other at eight in the evening. We would meet every day and talk over what was going on. There was this sort of problem-solving meeting to address technical issues, which were difficult. Someone might have done calculations, but in the end you have these buildings that are teetering on the verge of collapse, held up by a pile of rubble. How do you know if it’s safe or not? What do you tell people who want to go and dig in front of it for survivors or, later on, for remains? There were a lot of really charged questions that required a technical response based on not a whole hell of a lot of information.

I got to know a friend of mine during this period, Josiah Ober, a classicist who now teaches at Stanford but was then at Princeton. His work is all about Athens , and he has this notion called “democratic knowledge,” which is the collective intelligence of a group that is functioning in a certain kind of organized way that has to include dissent. So, when the Athenians were deciding how to repel the Persian invasion, they argued about it until they figured out the right thing to do. No one person had figured it out exactly.

As the situation evolved there were various attempts to privatize the whole recovery operation and put it into the hands of Bechtel and others. It was interesting to see how the public sector repelled those attempts. The characters who were showing up from the private sector offering to do it better clearly didn’t know what they were talking about. That was heartening and inspiring.

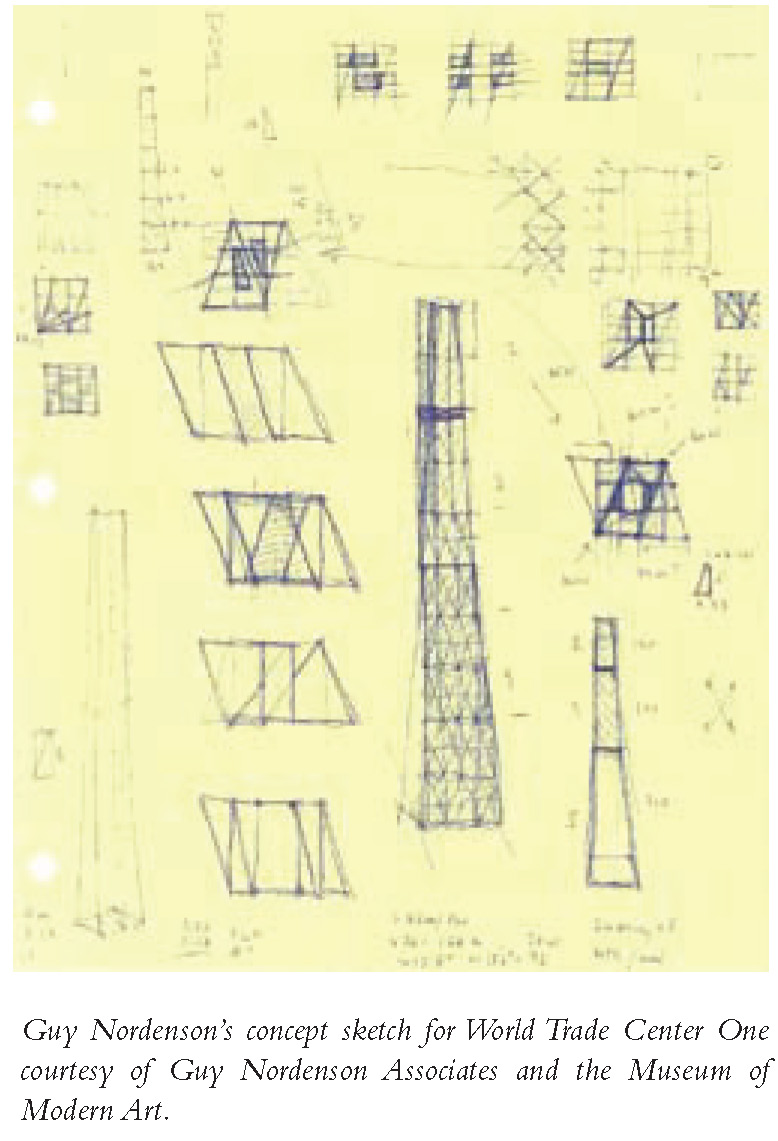

BLVR: Herbert Muschamp’s article “Thinking Big: A Plan for Ground Zero and Beyond” (the New York Times Magazine, September 8, 2002) included a design for two new World Trade Center towers whose structural concept you worked on. Where did they come from?

GN: Herbert showed up one day with these candlesticks he had brought back from Italy, which he loved, which were torqued, and a little model of a twisted tower that Gehry had done in Germany, which he also loved. He said, “I think that this is in the right spirit for what we need to do. How do you engineer this?” I thought the thing was a bit too easy and gestural. So I said, We’ll investigate the engineering implications. It was kind of interesting, actually, because when you take something where the windward and leeward faces become the sides, you do get an interesting distribution of stresses as you go down the building. That investigation was published in the article.

Then David Childs picked up on the idea. He also picked up on the fact that there was a connection with Herbert, who was influential. Childs contacted me and asked if I would help with the tower. I started in May 2003, and intuitively I sort of understood that there was no way of knowing where this would lead, so I might as well experiment. I took David’s idea that the building ought to fill the site, which was this parallelogram, played with that, and came up with the notion that instead of twisting the building entirely the way that Herbert’s idea did, the way Frank Gehry’s idea did, you could take two faces of a building and rotate them to get a tapering form.

BLVR: You walked away from the project. I heard it was because there was no more room for collaboration.

GN: Maybe there was too much collaboration. I was really opposed to what seemed to me to be the kind of connotative aspects of Daniel Libeskind’s design, which had to me a crystal-architecture feeling. In the context of Bush’s jingoism, it was just too much. So, with David Childs, this was an opportunity to fight it rhetorically. Then Pataki decided the best solution was some kind of collage of the two. He told Childs he needed that, and Childs dutifully tried to execute the collage. At that point it seemed like just the right time to push the eject button.

BLVR: Has your experience with the Freedom Tower informed the way you are thinking about proposals for Palisade Bay?

GN: My particular episode is just one within a longer story. I refuse to call it the Freedom Tower. You know, it’s a little bit of a Rashomon thing, where everyone has a certain response to Ground Zero. But I have to say, over time all the contesting forces and energies at every level have led to an outcome that isn’t so bad. I don’t particularly like the result, but mostly what I don’t like about it is the name. Strip away the name and the 1,776-feet jingo ism, and you’re left with a building—it’s bulky, maybe. The other towers are equally of interest, in particular Fumihiko Maki’s tower that the Port Authority’s going to occupy. The Memorial is compelling. So this democratic process has happened, in a way.

If there is a compelling argument for an intervention into the Upper Bay and along its border, it is that it will help us from a climate-change point of view; it will help us improve the ecology of the region; it will help us understand each other across the bay, New York vis-à-vis New Jersey; and it will decenter the region away from Manhattan. If it does what Central Park did, then people might feel compelled to move it along. A good idea catches on.