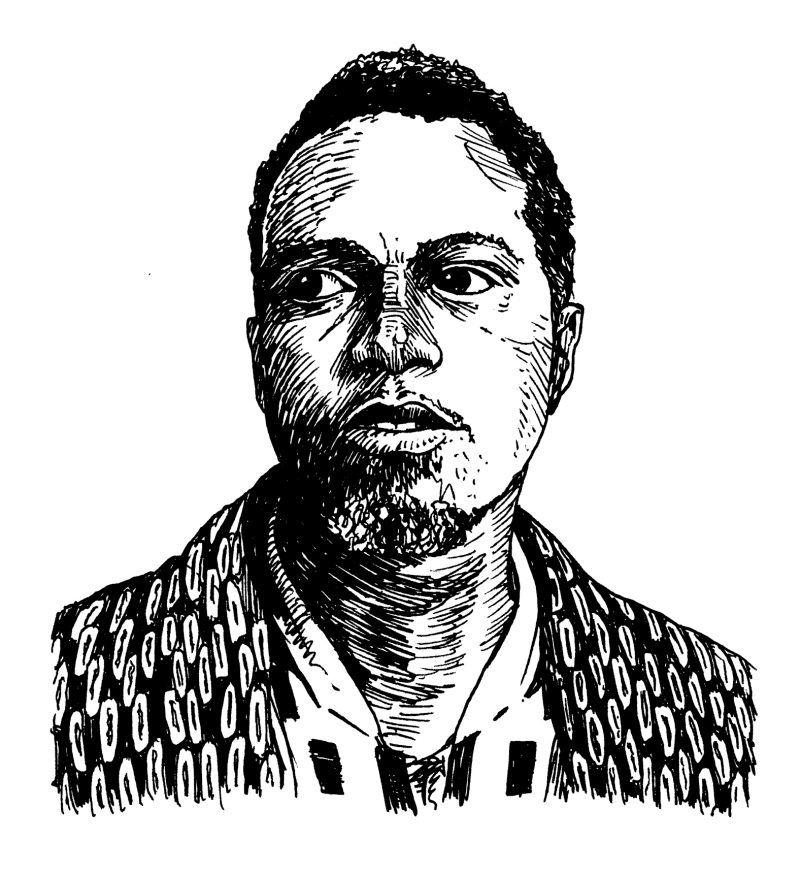

Ishmael Butler may be the world’s first “insider artist”—he’s bright, articulate, handsome, gracious, and obviously not weird, yet he creates kinetic, ecstatic, utterly cool music not from any margin. He’s been in and out of the music business since 1991, when he had his first big break under the persona “Butterfly,” playing in the jazz-inspired hip-hop trio Digable Planets. Their debut, Reachin’ (A New Refutation of Time and Space), was a commercial hit, and over the next decade he released two more Digable Planets albums, and one under the persona “Cherrywine.” Eventually, sales decreased and the band underwent multiple breakups.

After recording a solo album in 1999 that was never released, Butler went into a cocoon of privacy, dedicating himself to his family. Then, three years ago, Butler dropped off some tracks with the Seattle producer Erik Blood—to “see what he could do.” The sound on the tracks was a densely textured, electronic hip-hop art-pop; he had partnered with Tendai Maraire, who plays mbira and is the son of renowned mbira player Dumisani Maraire. Soon, their two debut EPs—recorded under the name Shabazz Palaces—began popping up in independent record stores around Seattle. The next year, they signed with Sub Pop, becoming the label’s first hip-hop act, and Black Up was released amid a solid flurry of attention, including fascinated reviews in the Los Angeles Times and on Pitchfork, earning spots on several prominent “Best of 2011” lists.

For this interview, we sat across from each other at Caffe Vita on Seattle’s Capitol Hill, not too far from where Butler lives with his kids, in the Central District, and where he spends time with THEESatisfaction, his queer neo-soul sisters and collaborators, who he helped out with vocals and sounds on their debut CD (awE naturalE, 2012). As this is being written, the bands are on tour together—a tour which began immediately after we met. As Butler spoke, he held the black, velvet-coated slipcover of Black Up, which he had brought along for the chat, rubbing his large thumbs up and down it. His manner evoked something of the 1970s, and a posh, pop-culture future just now beginning.

—Chris Estey

THE BELIEVER: You grew up in Seattle, then moved to New York to intern for Sleeping Bag [Records]. Did you enjoying working at a label?

ISHMAEL BUTLER: Yeah. I was young man, and back then—this was ’89, in New York—hip-hop was tripping. It was boss. I had ties there, I had family there, I had been going there since I was a kid, so I had a place to stay. A friend of mine had a big apartment and...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in