Miranda July might be a performance artist who makes films, a filmmaker who writes fiction, or an author who creates performance art. Or perhaps the idea of being defined by just one of these forms is precisely what she’d most like to avoid as she travels fluidly through each medium, transferring the attributes of one into another with seamless grace. Her keen deployment of narrative keeps her performance work from feeling dry and excessively theory-driven, and her films resonate with an artfulness largely missing from contemporary cinema. Her work has been featured in the past two Whitney Biennial exhibitions, and her directorial debut, Me and You and Everyone We Know received the Camera D’Or at Cannes as well as a special jury prize for originality of vision at Sundance. She did not, as a child, feed Cheetos to other, younger, children.

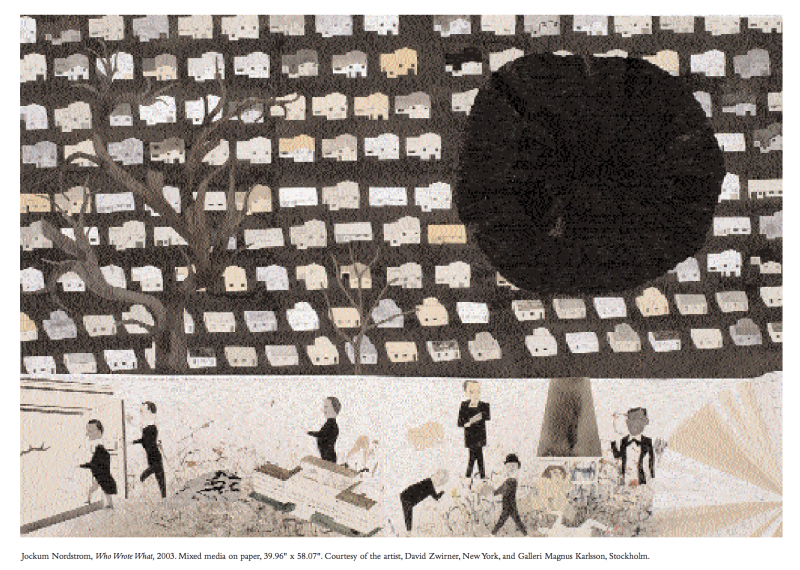

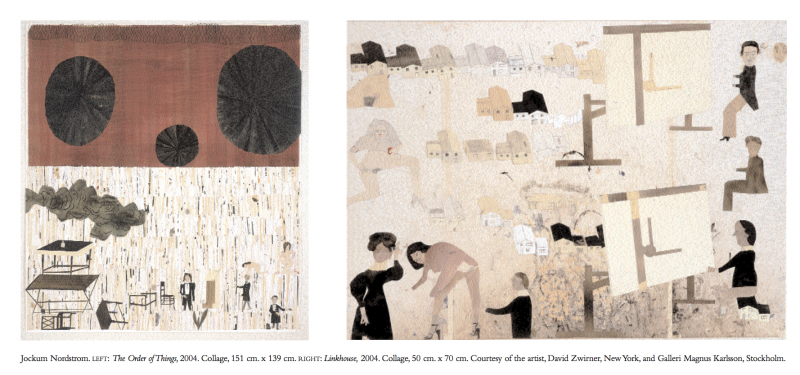

Jockum Nordstrom was born in and lives in Stockholm, where he makes drawings of ships, tiny dioramas of cities, and men in uncomfortable suits, all rendered in a deliberately crude folk-art style. His compositions are spatially dimensionless, but the figures that populate his odd, rickety landscapes are vividly—even lewdly—robust, the rich mysteries of their private lives pooling suggestively in the impossibly steep and cavernous rooms through which they move. These might be the banished mating diagrams of the early settlers—swiftly illustrated erotic comedies that barely made the leap from the elaborate theater inside Nordstrom’s head to the collage-laden page.

In September 2005, July met with Nordstrom in Manhattan. July had just returned from the French opening of her film, and was visiting New York for a premiere, and Nordstrom was in the U.S. to attend a wedding on Long Island. They wandered the Lower East Side, eventually settling in Nordstrom’s hotel room for a conversation on art, the deceptive warmth of Spain, and a group of tourists they followed around and dubbed “the Tribe.”

I.

MIRANDA JULY: Last night I dreamt that—I think this was an anxiety dream about global warming— I dreamt that I was the only one who realized that the sky was being digitally replaced by a fake sky—like, when you looked up you could see that there were these little, sort of—

JOCKUM NORDSTROM: It looked like that yesterday.

MJ: Oh, it did?

JN: Yes.

MJ: Oh.

JN: The sky was short—it was like a theater.

MJ: Maybe that’s where I got the idea.

JN: It was a really short sky.

MJ: In the dream I kept saying to people, “Look, you can see that little part isn’t real.” I realized that this had been happening slowly over many years—the government was doing it for some reason—and my proof was that people used to say “the sky’s the limit,” but no one said that anymore, because we all knew subconsciously that the sky was fake—that it was very short.

JN: That’s scary.

II.

JN: There was one part in your film [Me and You and Everyone We Know], the part about the macaroni woman? For me it was—I like that part, but in the end, I didn’t understand that you were coming back, and you have a show that…

MJ: Oh.

JN: I was expecting that it would end after she was in the park with the little boy. That was a good ending for me.

MJ: So you don’t have a question, just more of a constructive criticism. [Laughs]

JN: Yes. I like when you dropped the film in the elevator. I just liked that moment. You gave her one more chance—this odd woman.

MJ: Well, you don’t see her again so the end of her story is on the bench, but I feel like when she calls and says “macaroni,” that’s enough, to say that—I mean it’s a little poetic, but…

JN: But it ends with you waiting for another call.

MJ: Right.

JN: Also the two boys in the family were really good.

MJ: Yeah, it’s so nice—everyone always says it must be so hard to work with children, but for me, I’m sort of at my best when I work with children because I’m really curious about what they’re thinking and what they’re going to do next, and that’s sort of how you want to be with everyone.

JN: The cast—did they know each other from the beginning?

MJ: No.

JN: It seems like some of them must have known each other before. The brothers?

MJ: No, no one did, not even the brothers. One was from New York, the other was from L.A. I hired everyone through auditions. It was all very formal.

JN: One of the girls—the gangsters—the tall one— I think I saw her in something else.

MJ: Really?

JN: Was she not in something?

MJ: Probably not, but I don’t know. Usually, the things I’ve made before— the videos I’ve made for art galleries—usually I do know everyone involved, so doing it this way was a little strange. I was thinking, “How is this going to be good?”

JN: What about the old man? I think I’ve seen him before.

MJ: Yeah,he’s one of these amazing character actors who’s been in hundreds of movies but, you know, he’ll have like one line. I remember I looked at his résumé and I thought, well, I should rent some of those movies that he’s been in.[Laughs] He was in Three Amigos, but he’s just one of the villagers—you know, always in a crowd.

JN: I’ve seen his face sometime.

MJ: Yeah, he has a wonderful face. I love those sort of pockmarks. I think he never quite reconciled that it was my film. He would look at me and he’d be like, “But you’re such an angel, and you’re so young, and there’s these parts in the movie.” He almost felt embarrassed for me, I think. I think the idea of a young woman director was probably more unusual to him than for everyone else.

JN: Do you want to make more films?

MJ:Yeah, because it’s turned out how I wanted it.

JN: When you do your next film, do you think you’re going to use yourself? I mean, like an actor?

MJ:Yeah, the thing is, I love to do that. It’s one of the only times I feel really—

JN: Happy.

MJ: Yeah. It’s really hard to shoot a movie, and acting made it more fun for me, to get to be a part of the world that I was making. It helped when I was writing, too. I’d be sitting at the computer, and it’s nice that the medium is people, because in fact I’m going to be in the movie, so I’m like the pencil, you know? I have myself already.

JN:Is it hard for you that people recognize you? For me, I don’t have this problem so much, because nobody knows how I look. Is it hard sometimes?

MJ: Before this movie, when people recognized me, it was always really special because I was lesser-known, and it meant that they had probably gone to some length [laughs],you know—they had really tried,so I felt almost like we had to go have lunch or something.

JN: Do you still do theater?

MJ:Yeah, I still do performance. In a way, that’s how I was more known before the movie.

JN: But now a lot of people recognize you.

MJ: Yeah, it’s funny because the places that I go, the people who would see my movie also go—bookstores and clothing stores and galleries. It’s like I’d have to go to totally different places… you know, I’d have to hang out uptown. [Laughs] A few months ago, when the movie first came out, I was really alarmed.

JN: Because you need privacy to make new stuff.

MJ: It’s been really devastating for my creative life. I’ve kind of had to let go. Usually, I’m like you. I have my notebook and I have to have had at least one idea, or notice one thing, like the Tribe.

JN: The Tribe, yes.That’s really good.

MJ: [Laughing] Yeah, maybe you can use the Tribe. But for me, when I’m starting out, basically as far as I get, it’s just the Tribe. I don’t get to go further and write the story about the Tribe, or make the video.I just notice them and that’s as far as I can get. I’m sort of filing ideas for later.

III.

MJ: When do you find yourself wanting to draw?

JN: I think for me, I have been drawing since I was two years old. I am always drawing and painting. For me it’s like eating. Before I was an artist who had exhibitions, it was easier. I was always drawing, but now it’s more like a job. Something is lost.

MJ: Right.

JN: Without this, I would be very sad. It’s a very big part of my life, and if I don’t have an exhibition I draw all the time.I’ll maybe draw this one two weeks before that one, and I’ll stuff them all in boxes and cabinets and then I take them out and look at them again and make changes.

MJ:And I know, when I’m making something, I’m really not—it’s kind of a combination of thinking and not thinking, and mostly I’m not thinking…

JN: You just have an idea, and that’s the way you go in.

MJ:Yeah, that’s like the door, and then you’re in.At what point did you know about the “art world,” or did you always know?

JN: No. I went to art school very early, when I was seventeen, but I didn’t know I was going to be an artist at the time. I was studying to become a teacher—for young children.

MJ: Oh, OK, and is that what you did?

JN: No, I drew all the time and played lots of music.

MJ: What kind of music?

JN:All kinds. It began with punk rock—

MJ: [Laughs] Uh huh, OK, yeah, in college.

JN: And after a while it was more like blues, early blues. And then I was playing more jazz.

MJ: So more and more adult. [Laughs]

JN: [Laughs] Yeah. But for me, the drawing was always more important, and the music was more a social thing, much more to make friends and have a good time together. And after school, four years in art school, I was very—you know, it’s like a black cloak, the future, and I knew I wanted to paint and draw but I didn’t know how to get money. So I went up to, I think, like, twenty publishers with my drawings in a briefcase. And I got a lot of jobs. I began to illustrate. It was very boring after a while. I hated it.

MJ: Did they give you assignments, tell you things to draw?

JN: Yes, I got a lot of deadlines.

MJ: What’s an example of something you’d be asked to draw?

JN: I was drawing for children’s magazines, and books for school, so—

MJ: Right, so like,“draw a ladybug”?

JN: Yeah, exactly. [Both laugh] And also English books— Learn to Speak English books, where I’d have to draw a woman walking down the street.

MJ: Right…

JN: Yeah, and one football magazine. A lot of that job was not good. So I worked for different publishers and made pictures for books, too. But after a year of that I went to Spain and Italy, just moved away in the middle of winter with one jacket. I thought it would be warm, and I was so cold, I was freezing, just walking around. That was when I decided I didn’t want to make these crappy pictures of a woman for magazines. It just wasn’t for me. I think I was around twenty-two or something. But I’ve always been drawing so much, if I look in the back mirror it was the only way…

MJ: If you look in the what? The back mirror? [Laughs, delighted]

JN: Yeah, if I see… If I look at my life from a distance.

MJ: Do you have work that you never show anyone? I mean, I have this—I work in these different mediums, even more than people know about. I actually feel like I’m a child, in that I’ll see something and I’m so inspired I think I might go home and draw, because even though I’m not very good and no one will see it, I’m actually making—like, I was in Paris last week, and I couldn’t write, and I didn’t have very much time, but I bought this very nice felt, like felt wool.

JN: Is it paper?

MJ: No, it’s like cloth…

JN: Like silk, okay.

MJ: I picked the colors very carefully, three colors, and I bought glue, and this is during my one-hour break—

JN: So you could make pictures like in kindergarten!

MJ: Yeah, I really felt—I was like, “oh!” and the things I had to express were anger—I thought that maybe I could actually describe my anger at the press [laughing] through a felt banner, you know, with pictures— and also my sadness at having to be away from home, away from my life at the time.

JN: Was it good in Paris, the film?

MJ: Yeah, it’s very good. They love it, my problem is my own.

JN: Do they have the text?

MJ: Yeah. There are subtitles.

JN: But they don’t take the voice out.

MJ: No.

JN: Dubbing, is what they call it.

MJ: No. I saw on TV that they often do that.

JN: In Sweden they always do that. In Germany, too.

MJ:That would be really exciting for me, actually—to see myself speaking French.

IV.

MJ: How old are you?

JN: [Awkward silence] I’m forty-two, I think. Maybe forty-one. I was born in ’63, but my birthday is close to the Christmas season, so I’m forty-one.

MJ:Well, I had a boyfriend that was born in ’62, so you would be his age. He was born in November.

JN: Yeah, I’m forty-one. I try to be forty-three.

MJ: I’m thirty-one. It’s funny, I realized with all the sexual things going on in your work, I think that because you’re a man and these are drawings, you get a little more of the space that I wish I had.

JN: Because drawing is more private, and to do what you do you must have actors, and you must have…

MJ: But even if it’s a short story, I realize—I’ll write a story and I’ll realize, sometimes I forget to say that this woman—she’s not thirty-one, she’s fifty-five, and she doesn’t look like me. I forget to describe her.And then I realize that when people read the story they’re picturing me as the protagonist. So then, when they read this sexual passage, it’s totally wrong. That’s why your space is so appealing to me.

JN: I think for me, I take one picture at a time. It’s not so much about making a room. It’s more like the one picture. I think a lot about how the drawing looks on the paper, but it’s also about relationships and memories and something that’s behind you, but you can’t talk about it. And you can’t find it every day. You can find it when you’re really in it. I think the picture and the speaking language are very different.

MJ: Yeah, I often feel like if I could say it, what it was, I wouldn’t have to make the movie—the movie is the thing. It’s the feeling, and to try and say what it is would be really clumsy. For me, too, it’s a lot about—

JN: Something behind.

MJ: Yeah.Yeah.

JN: It has a lot to do with memories, something you’ve seen, and you’re trying to make it one more time. But sometimes it’s more about relationships.

MJ: And for me, sometimes I’ll have something that I wrote down, to use the Tribe again as an example maybe [laughs], just an image—something that caught me—and I don’t know why. I’ve noticed it. It doesn’t matter what the thing is, it’s just that when I sit down it’s like the road and the thing I’m putting in it is all me and my sadness…

JN: You don’t know, exactly.

MJ: Right, and so it—it just happens to be able to move, like the Tribe is the car, and you’re taking it down the road. For me it’s a little frustrating. People see the “peep peep” thing in my movie and then ask me, like, “Oh, is that you when you were little?”And it’s like,“No. Just a friend of mine told me. And he wasn’t emotional about it. It wasn’t special.” But I just had the image in my head and I think I drew a star shape in my journal.

JN: You wrote down that the girl would feed the other children?

MJ: Right.

JN: And there was another thing in the film, the two young girls who were going to have sex with that man, I was afraid that something terrible—

MJ: Would happen to them?

JN: Yeah.

MJ: But then it doesn’t.

JN: It was good how it changed. I liked that it was more like this.

MJ: Yeah. Yeah, I know. That scene where they’re just running away from me, that was…

JN: And looked at each other. It was relief.

MJ: I probably feel a lot more than what is actually there on the screen, but for me it’s like all the times when my best friend and I would have built something up as this really exciting thing, but we always ended up back with each other, just thinking,“Oh, it didn’t work out.” And we’d be kind of glad, because we really are happy just to sit in the kitchen and talk.

JN: But the feeling, I recognize from my own life, is very good. It’s really good.