In the late 1960s, John Baldessari cremated all the paint works he had produced between 1953 and 1966. He announced the event to a journalist so the world would know that he had stepped outside the confines of artistic tradition. Soon after, he began rooting around in Dumpsters for found imagery (newspapers, movie stills, advertising posters) and collaged these visuals with found written texts (broken signs, ripped newspaper headlines) in a way that offered a plurality of narratives—questioning just how relative our ideas of meaning can be.

Based in California for most of his life—save a decade-long hiatus in New York in the ’60s—Baldessari has always delivered a gently caustic sense of humor in his work. Like Warhol’s or Ed Ruscha’s, Baldessari’s understanding of the visual language of communication on a major scale—or, more specifically, advertising—has allowed him to simultaneously subvert and worship the bright colors and smirking politicians that surrounded him every day. On the phone from his studio in Venice, L.A., Baldessari’s voice is so deep and rumbling that it’s sometimes hard to make out what he’s saying. He said he was used to repeating himself.

—Eleanor Morgan

I. THE IMAGING OF PEOPLE

THE BELIEVER: Is it fair to say that in the beginning of your career you were trying to break certain gallery taboos?

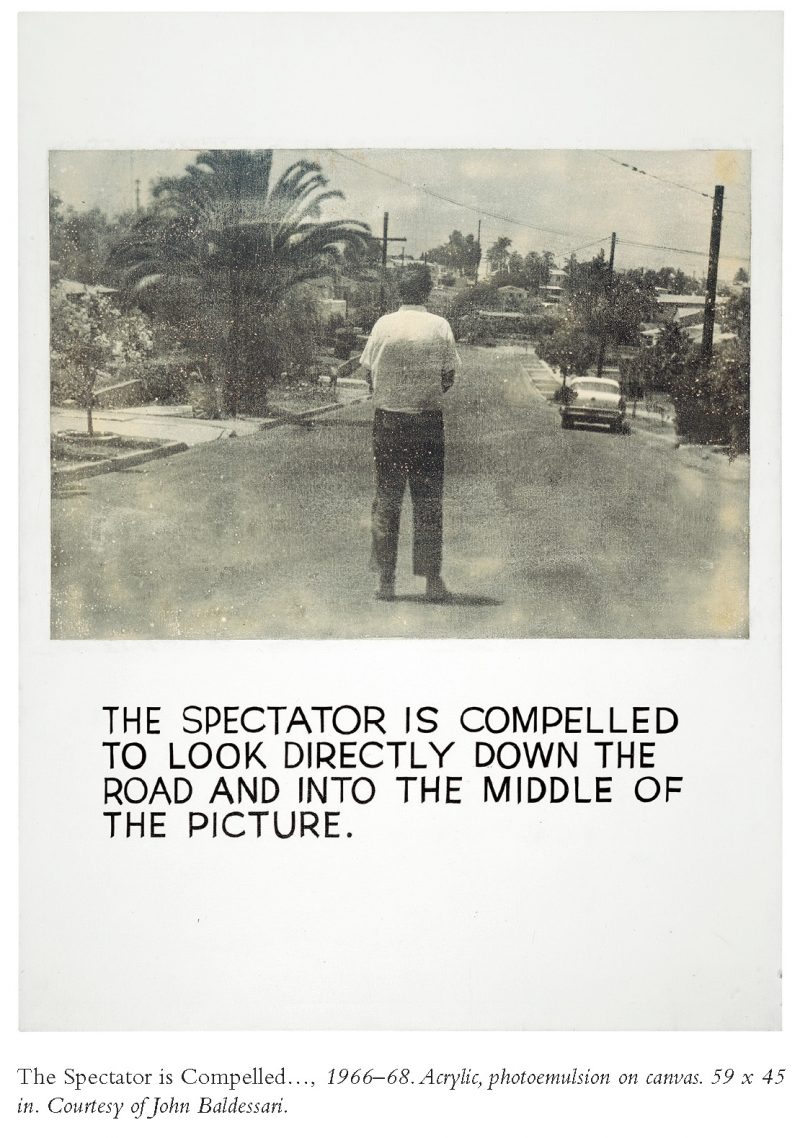

JOHN BALDESSARI: I had a few battles there, yeah. But it certainly is true: I wanted to challenge, and ultimately break, all these taboos that art galleries had at the time. You never saw photographs in art galleries— they were always in photo galleries. So I wanted to make photography a tool that artists can use, as opposed to something they can only, well, look at.

BLVR: You did the same thing with introducing text into your work.

JB: Absolutely. I became very interested in the prospect of using language as a tool for art, and informing the work in a different way. It wasn’t just about the visual appearance of the language, either. It was about giving a different platform for understanding the work. Most of the text was “found,” as well—broken signs, segmented newspaper headlines, things like that. I just appropriated bits of it and gave it a different course.

BLVR: Were there any artists whose work with text had informed you?

JB: Picasso was the main one. But Lichtenstein and Braque did it for me, too.

BLVR: You abandoned painting quite early in your career and cremated every piece of painting work you ever made. Can you tell me a bit about this?

JB: Oh god. I was drowning in paintings by the ’70s and becoming more and more doubtful that painting was the only true way to do art. It occurred to me one day— when I’d totally lost the drive to paint another thing— that I didn’t have to own these works anymore. I was certain that no one was ever going to buy them—plus, I think I had a slide record of almost all of them. One of my first ideas was to photograph each painting and turn it into a micro-dot and put it under a stamp on letters that I’d mail to my friends. I think I’d been watching too many movies. But then I got to thinking about this idea of my work as something cyclical, you know, with some element of return. I thought that all these canvases, materials, oils, and pigments that came out of the ground should return to it. All the painting I did was a body of work, so I thought I’d cremate them together, literally as a body.

BLVR: Wow. How did you find a crematorium that would do it?

JB: It was pretty easy. The guy that did the actual cremating had studied art in the past and was quite into the idea. In the end we had nearly ten boxes filled with the ashes of my work. I burned everything in my possession—which, believe me, was about 99 percent. There were a few that didn’t make the flames—those that were in exhibitions or with curators. I’m pretty sure there are still a couple of stragglers around today, but I have no idea where.

BLVR: In abolishing all of your painted work, it’s as if you dispensed with all classical notions of art. You could move forward in any way you pleased.

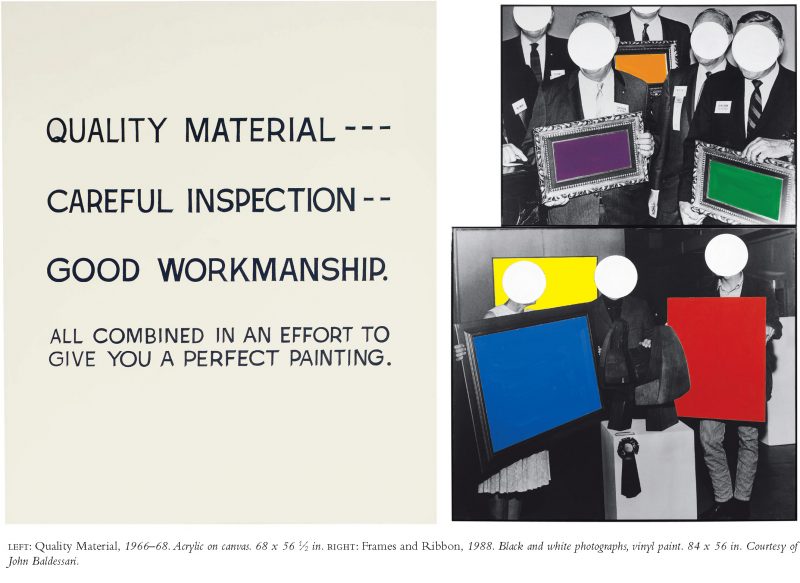

JB: It’s true. And I felt kind of the same later on, when I started to use found imagery in my work. I was basically trying to be artless. I thought that the more I became involved with art and the art world, the more artful I was going to become. I really wanted to get out of that, so I thought I’d let other people do things for me—or use the imaging of other people.

BLVR: Where did you find all those photographs, press images, newspaper cuttings, etc.? I have a great image of you upside down in a Dumpster with your legs in the air.

JB: That vision is pretty spot-on. There was a lot of rifling through garbage in the ’80s. But I also collected a lot of photographs from local newspapers—there’d be celebrities, public officials, those crazy openings of a store or whatever, where someone would come and snip a ribbon. I didn’t know what to do with all the images I had at first—I found them repulsive, but fascinating at the same time.

BLVR: No matter how odd the images that you used in your photomontages were, they have always felt quite familiar. It feels like we’ve seen them before—I suppose because a lot of press photography looked the same back then. But did you have a sense of style in your head when you were scavenging for these images? Was there anything that unified what you found?

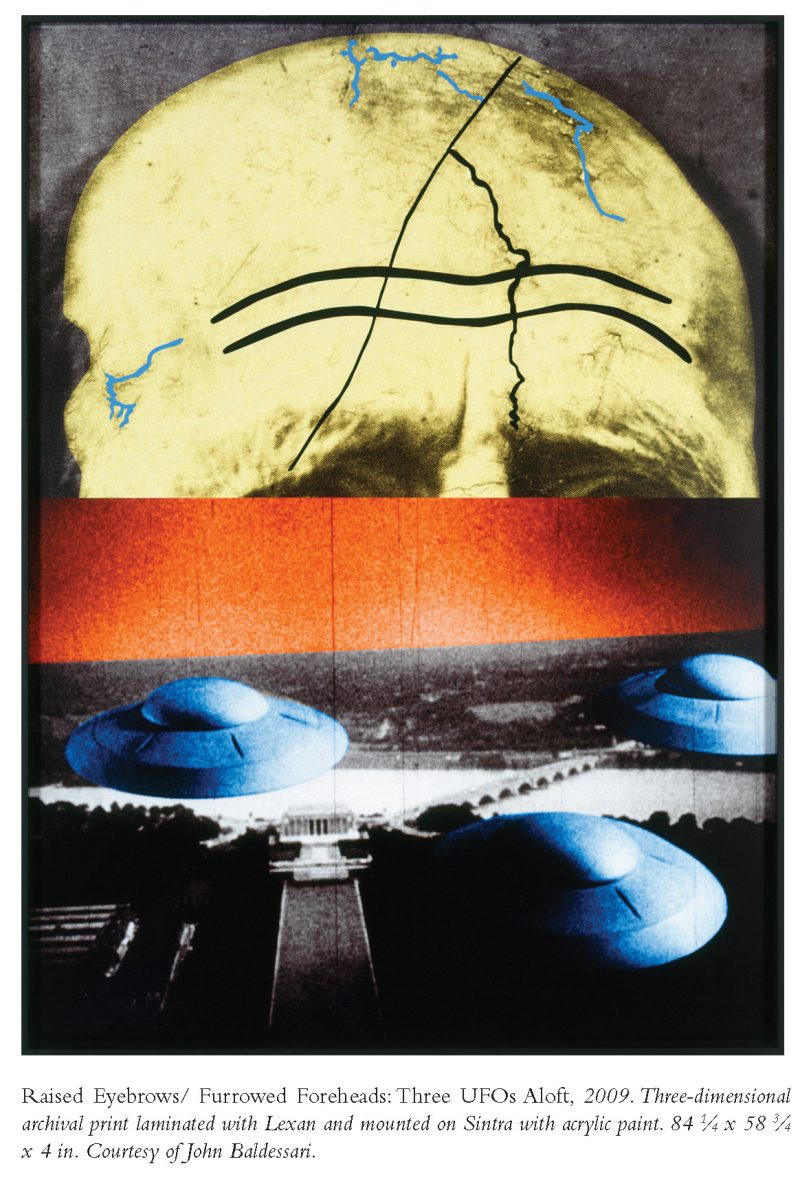

JB: No, no, I don’t think so. Although that’s a good question, because you’re referring to imagery that most people are privy to in some way or another. There’s all this imagery locked inside our heads from all the newspapers we have read, and we don’t even realize it. I became aware, at some point, that these images would be useful to trigger people’s unconscious somehow, and, like you said yourself, feel like you’ve seen them before. By working in this way, I could tap into this universal bank of images we all carry around with us in our heads. But then I started to want to juggle things around, to change the narratives of the people in the pictures.

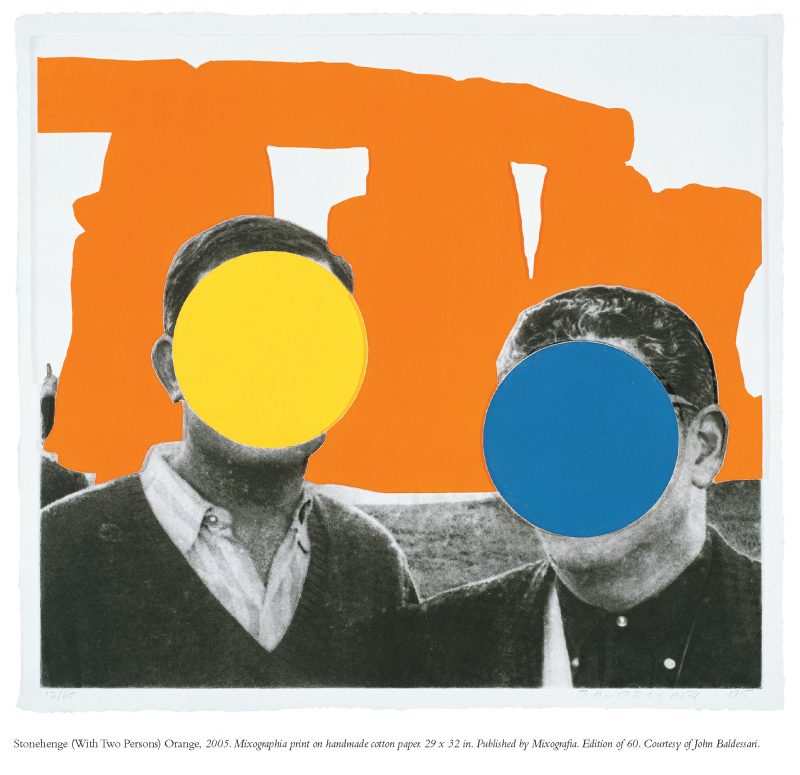

BLVR: Right. So that’s why you started covering people’s faces with those neon dots.

JB: Exactly. I had these price stickers—or neon dots, as you say—that I was using for other works, and just started putting them over people’s faces. I thought, Wow, this really levels the playing field. I felt like these were people that were controlling my life—the politicians were every where I looked when I walked down the street, on every newsstand on every corner. They filled my vision and my head. So by covering their faces in this way, they were no longer specific people. They were generic people, say, the fire chief or the postman. They were the guy next door, and became actors in my own scenario.

BLVR: When I look at those works, it makes me question my visual prioritizing, too, because you normally look at a person’s face first.

JB: Right! That was a big element of what I was doing as well. In a way, I was diverting people’s attention away from what they normally look at. Using those dots also, in a way, flattened the whole image. Because the people have no distinguishing features or character, every element of the piece is as important as the other. It all becomes one and the same, and that idea excited me tremendously.

II. TO THE PLAUSIBLE EXTREME

BLVR: In the early 1970s you made some iconic video works, like I Am Making Art (1971), Teaching a Plant the Alphabet (1972), and Baldessari Sings LeWitt (1972). How did the video work come about?

JB: I was working at CalArts at the time, and the Sony Portapak had come out, which was the very first portable recording device. I was just one of many artists who started filming themselves. Although they were just meant for my students, and I—I never really intended for them to go beyond that.

BLVR: I think what’s so interesting about them, though, is how they mock other conceptual artists. They’re like a comment on the times.

JB: I think I was trying to explore the idea of an artist making choices, and that the result, by default, becomes “art.” If I made a slight body movement on film—lifted my arm or nodded or something—it was a conscious choice, so I was making art. Pushing things like that to their plausible extremes excites me. But I took that idea and ran with it—it becomes ridiculous what you can get away with, really.

BLVR: Was film sequential to working with photography in your mind?

JB: Definitely. I think what I was trying to do is find out what the differences were between photographic film and video. In my head, video was the natural progression from 35 mm film—and the theory works if you reverse it, too. Videos are just lots of frames one after the other.

BLVR: I’ve seen the term “static cinema” applied to your work a lot, and read that you watch movies obsessively. Has cinema always been a big part of your life?

JB: Oh yeah, always. I watch a couple (sometimes even three) movies a day, still!

BLVR: How has your relationship with cinema influenced your work?

JB: I think if you’re storing all these images unconsciously, you never know when they are going to come out in your work, or from which film. It’s an exciting thought, not knowing what’s going to trickle out where. It just happens, and it’s only when it happens that you can sort of identify it.

BLVR: Do you have a “waste not, want not” approach to art?

JB: Yeah—and in almost everything else in my life! I was born during the Depression, so I’m bound to be like that. I have an inbuilt aversion to throwing stuff away. Actually, more like a complete inability to throw stuff away. I used to drive my assistants absolutely crazy—if they threw things in the trash can, I’d pull them out and ask them why they were throwing away a perfectly good piece of paper. It was like I was personally offended by it!

BLVR: Your parents were both immigrants—you have an Austrian father and a Danish mother. When you were younger, did you feel like your home life was different from your peers’?

JB: It was and it wasn’t. But my parents were different from my friends’ parents, sure, and not just because of their nationality. We ate different food than everyone else—that was a big difference. My mother was incredibly health conscious and made all these healthy things like brown bread and vegetable juices. My parents had become totally self-sufficient by the time I was born, at the end of the Great Depression. They grew all our fruit and vegetables, and we had chickens and rabbits. We filled huge bottles up with spring water at the weekends. My mother and father came from entirely different social backgrounds—she was middle-class, and he had grown up with eleven brothers and sisters. His house was divided so that the family lived at the top, and all the livestock lived at the bottom. As soon as he could, he collected his earnings and left for America.

BLVR: Was there a language barrier with your parents?

JB: With my father there was, yes. Not with me, per se, but I had to explain a lot of things to him. I’d have to go through so many ways of putting things before he’d understand—which was strange, but kind of like the way I went on to approach my teaching. And my art, I guess, in the sense that I always wanted—and still want—to create a middle ground of understanding. I don’t want anyone to be left by the wayside.

BLVR: You were a teacher of art for so long. Why did you give it up?

JB: It became a difficult situation for me. I didn’t need the money, but the fundamental reason was that I couldn’t be there enough for the students. And my philosophy is that if you’re not there for a large portion of the time—if not the whole time—then you’re really cheating them. I just got to the point where I thought it wasn’t fair.

III. A CLOSED ARTIST

BLVR: What struggles do you think young artists face today?

JB: I think the main thing is that for some—if not most—of them, it’s hard to disassociate art from money. What I want to say is that money does not mean quality, you know? You can easily live on the assumption that if a gallerist isn’t picking up your work, then there’s something wrong with your art. But a gallerist has to pay the rent, and it sort of doesn’t matter— well, it does, but I am making a point here—whether they like your work or not, they have to be able to sell it. If they think they can sell your work, they’ll give you an exhibition. That’s the size of it. Retaining self- belief when galleries aren’t picking you up is incredibly important. It’s not all over if it doesn’t happen straightaway; you just have to keep at it while you’re earning money somewhere else.

BLVR: There’s a big flux of young artists now who are making a lot of money very quickly by doing lots of commercial work. How do you feel about that?

JB: That’s a tough one. Fundamentally, though, if you’re an artist who has making money as your main goal, then you’re a business, not an artist. You’re making a product. It’s a fine line—I have no problem with people that sell their work, but if money is their ultimate goal, then I think they’ve got it wrong.

BLVR: How many artists do you think can actually live off their work?

JB: It’s depressing to think about. Probably less than 10 percent of all the artists in the world.

BLVR: That is kind of depressing.

JB: Yeah, but think about in the sports and entertainment industries. It’s the same thing. There’s this top layer of people making ridiculous amounts of money, and thousands of others working really hard and earning very little. I always tell people when they’re starting out, “If you want to make money, be a plumber. You’ll get a good living out of it.”

BLVR: Do you think there’s more money being exchanged in art now?

JB: Oh yeah. When I started out, if you sold a piece, the joke was “What are you doing wrong?” Art has a far bigger currency than it ever used to.

BLVR: Do you think it’s fair to say that as a working artist, you have to put your “real” life on hold a little if you really want to succeed?

JB: Pretty much. Until you get to a certain point, being an artist is no luxury. And unless you are totally obsessed with making art, you’re not going to make it. At some point you may want to settle down and have a family, and it’s hard to navigate that if you’re a hungry artist. What it boils down to is balance and realism. You have to be realistic about how you will support yourself.

BLVR: Have you ever, at any point, thought about giving it up?

JB: No. It would be like stopping breathing for me. Believe me, it would take something pretty big to make me stop making art.

BLVR: Like what?

JB: Well, my worst fear is repeating myself and becoming a parody of my work, if that makes sense. If I ever felt like that—well, I don’t want to think about it.

BLVR: I’ve spoken with many artists who say that their chosen path has meant that they’ve had to work hard at fighting off depressive tendencies—with all the long days to fill and the loneliness and unpredictability that come with working for yourself. Is that something you ever grappled with?

JB: Not really, because I never had the idea that my vocational goal was to be an artist. When I came out of school I went straight into teaching and really resigned myself then to that life—teaching, marrying, having a family at some point. Back then, art was something I enjoyed doing at weekends, so I never thought about it that way. Then one day I was offered a teaching job two days a week for more money than my other job teaching five days a week. Suddenly, I could see the arc of my life changing. Being a real artist seemed, for the first time, a true possibility. So I guess I never had time to get depressed.

BLVR: You lived in New York for a while in the ’60s, right? Did you ever think about staying in New York?

JB: It’s funny you say that. I had thought about living there, but then I got married to my wife, and she didn’t want to raise children in New York. When my two daughters learned about this, they were so angry! I think they’d have preferred to be brought up in New York. But really, I didn’t need to be there—I had made my mark in Los Angeles, and had everything I needed there.

BLVR: Do you think there’s still a distinct East Coast– West Coast delineation in the art world?

JB: If there is, I don’t know about it. But there was certainly a huge divide back then—not even a divide, really, because New York was the center of the art world. I’m not sure if that’s the case now—you’d have to ask someone a little younger than I am. Art is so in your face over there, you can’t turn a corner without coming across a little gallery. In a way it’s a blessing to be in Los Angeles, because there is nowhere near as much art going on. For me, that makes it easier to work.

BLVR: In the introduction to Wallace Shawn’s new book, he says, “I’ve passed my life largely in a fantasy world. My personal life is lived as ‘me,’ but my professional life is lived as other people. In other words, when I go to the office, I lie down, dream, and become ‘someone else.’ That’s my job.” As a conceptual artist, do you feel like you have to sidestep yourself in order to create something, well, conceptual?

JB: You try to keep your own life out of your work as much as possible—but it’s hard. In the beginning I was a completely closed artist—I kept all my personal thoughts and emotions very close to my chest, and think I did quite well at removing them from my work. The conscious stuff, anyway. But you—well, I—want to be somehow universal, and you have to be much more open for that, I think. I’ve got to say, though, that it’s virtually impossible to stop hidden morals from seeping into your work, no matter how detached you claim to be. Little bits are going to seep out on a level that you can’t possibly control.

BLVR: Looking at the timeline of your career and various interviews you’ve done over the years, it’s quite startling just how much you’ve done in terms of your body of work. You must never stop.

JB: The long and short of it is that I don’t. I’ve never stopped. Except from doing the things that fathers and husbands do.

BLVR: Do you have a daily routine that you’ve always followed?

JB: I refer to my friend Lawrence Weiner, who once said in the press that I was a “9-to-5 artist.” I think that’s most accurate. But, yes, I’ve always structured my day in the same way wherever I can—get up around five, read for a couple of hours, and then make breakfast. I get to my studio around ten a.m. and stay there until six or seven. Even if I don’t do any work, I just like to be there. To me, it doesn’t matter if you spend four out of five days cleaning the place—soon enough you’ll get bored of doing that and actually create something.

BLVR: Do you go into the studio every day?

JB: Yeah, it’s my life. I’m not here five days a week, I’m here seven. I’m separated and the children are gone, so it’s not like I’m upsetting anyone by being away so much.

BLVR: What do you do in the evenings?

JB: When I get home in the evening, I cook dinner, do the dishes, watch a couple of movies, and maybe read a little. Then I go to bed, wake up, and do the same thing. I’m a real bore, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.