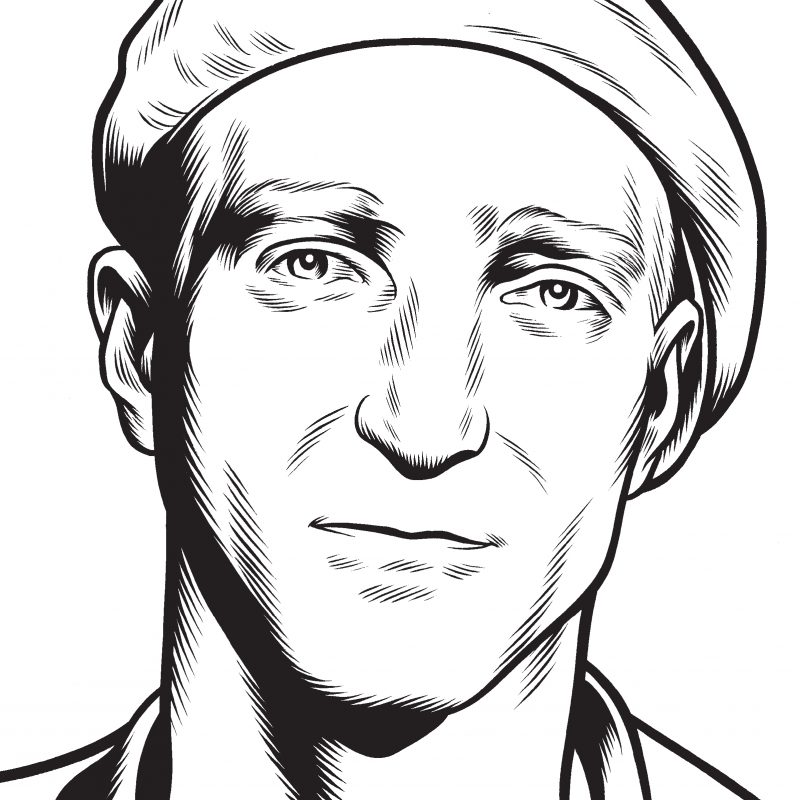

Jonathan Ames was a fencer at Princeton University, which is also where he began writing. Since 1989 he has published three novels, four essay collections, a graphic novel, and several short stories, all of which blur the line between the fictional and real Jonathan Ames. Ames also edited Sexual Metamorphosis, a collection of memoirs on transsexuality, a subject that he explores at length in his writing. An HBO show, Bored to Death (based on his short story of the same name), airs this fall, and a film adaptation of his novel The Extra Man is currently in postproduction.

I first spoke to Ames in Iowa City in the fall of 2007, when he was a visiting professor at the University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop. We sat down for an interview directly after Iowa’s NonfictioNow Conference, at which Ames performed monologues. The last two years have been some of Ames’s busiest, and to chronicle his progress, we met twice more. The three discussions have been arranged here chronologically.

—Andre Perry

I. NOVEMBER 2007, IOWA CITY, A RESTAURANT

THE BELIEVER: You lay a lot of your life out there in your nonfiction work. You keep giving us all of these pieces of Jonathan Ames. There’s so much confessional going on. But what are you not showing us?

JONATHAN AMES: Well, if I could answer that question, then I would write about it. But what I’ll say is this: I guess I am still writing essays, but I think a slightly false impression comes out that I’m doing it all of the time. I wrote a column for almost three years in which I had to produce every two weeks, fifteen hundred words. So I basically came up with three books of essays—all very confessional—all of which came from this column I did for New York Press. And they published almost anything I wrote. They gave me great freedom and I kept coming out with nonfiction. I was making money and having fun with it, but since I stopped writing the column, in 2000, I’m not confessing as much.

It was in my late twenties and early thirties that I was doing, as you said, a lot of confessing. I was doing monologues onstage all the time. My first novel (I Pass Like Night, 1989) had a lot of dark material, stuff that people wouldn’t write about: prostitutes and all sorts of weird sexual behavior. That was risky, doing that stuff in my first novel and then writing it in the first person. And then after that, from 1990 to 2000, for ten years, really, I was confessional: performing a lot, writing lots of nonfiction, and using myself as the subject.

Then, since 2000, that’s seven years now, I still do it, but not with the same frequency and probably with increasing trepidation. Because as you get older it’s harder to put out that stuff where you take a risk. Like in the [Marilyn] Manson piece I did [for SPIN], I took a risk acknowledging that I was drinking absinthe with him all night and implying that we were doing cocaine together. I mean, these don’t sound like such bad things, but my family, I don’t like them to know about all of this misbehavior.

So your question was: what am I not telling? A lot of what I don’t tell is the sheer volume of my life. I read my journal sometimes and think, Woah, I’ve got a lot of energy! I’m doing a lot of running around, or what a psychologist might call “acting out.” At some point I stopped writing about a lot of it because it was redundant. You can get away with saying, “I went with a prostitute once and here’s the story,” because people think, Oh, he did that a few times. They just don’t know the sheer volume.

BLVR: Do you ever find yourself playing into the “Jonathan Ames” that you’ve created in your essays? Do you ever find yourself living life and being like, “Well, if I just push a little further tonight, I might end up with an essay?” Do you live in order to create the material?

JA: Not so much now. When I had the column and I had this “every two weeks” deadline, there was a relentless recording going on in my mind, thinking: Is this a column or is this a column? You know, I was getting two hundred and fifty dollars a column, which was five hundred a month. I liked writing the column because in New York, at the time, it was pre-Internet and people were still picking up the alternative paper. So in my little village—the East Village or Brooklyn, wherever I was living—people were reading that paper, reading my column. And it was fun. You write something on a Tuesday, you send it in on Wednesday, then it’s out the following Tuesday, and then you’re getting feedback, and there would be letters in the paper the next week! So I did enjoy writing it, but at the same time it was like a gun to my head. Only a few times did I really push situations so that I might write a column about it. I think it comes out in my second book of essays (My Less than Secret Life, 2002). I was invited to an orgy, and I’m not really into group sex, but I was thinking, “Yeah, this could be a column.” And I was a bit curious too. Again in that book, a friend of mine was doing an animal sacrifice—she’s into voodoo—and I normally wouldn’t have participated—well, I don’t think I would have. I mean, I do like to do weird things, but there was this voice in my head going, “This could be a column. Go do it.” I had to watch this chicken being killed.

BLVR: So if you’re moving from the confessional, what do you want to do with your nonfiction in between the novels? What’s interesting to you?

JA: Well, for example, I’m writing about this Hatton/Mayweather fight. I’ve never been to Vegas, so I’ll probably have fun trying to describe Vegas, but I won’t go overboard, because Vegas has been written about so much. I’ll try to write about the fight, find humor, and write tight sentences, but I also like getting into scenes. SPIN magazine sent me to a goth music festival in Illinois. I don’t know anything about goth music. I didn’t even know what it sounded like. But I went and I enjoyed being in that subculture, interviewing kids, getting touching stories, and when I write these nonfiction things, they become like diary entries, ’cause I’ll keep the pad: “At 1:15 p.m. this happened”—for me, time creates narrative. Rather than do this overall global view of the goth music festival, I can write it in a diary form, taking you through the way I experienced it: I arrived here with this frame of mind and left with this frame of mind. So I constantly do these nonfiction pieces the same way. It’s like a freakin’ diary. I went to the music festival, I liked meeting the weird kids, I liked being in the weird scene. You gotta be on top of it. You gotta take notes and ask questions. You can’t just absorb: you gotta get some data.

BLVR: When you sit down to write an essay, what’s your process of getting it out once you’ve gone out on assignment or finished the experience?

JA: For me I tend to write in a linear fashion. I’m not saying all of my work is like this, but I am somewhat addicted to beginning, middle, and end. For my Marilyn Manson piece, I began with my approaching Manson’s house, and from there I just did a linear narrative. That’s my process. I start at the beginning and see what happens. I even keep my notes in a chronological fashion.

BLVR: Are you afraid to break with that tradition? Is there ever a time when you’re sitting down and you say, “Fuck it, I’m just going to get experimental with this?”

JA: I’m not an experimental person… with my writing. I’m just not. I am addicted to narrative. There might be flashbacks or tangents, but I really work best starting at the beginning. I see the appeal of goofing around and riffing off and then coming back to a bit of story, but, I dunno, I always worry about boring the reader. I might be limited, but I play to my strengths. In basketball, Shaquille doesn’t shoot from the outside. You know what I mean? Does anybody fault him? He just shoots from the inside.

II. DECEMBER 2008, IOWA CITY, A RESTAURANT

Ames returned to New York after his visiting-professor gig at the Writers’ Workshop in Iowa City. In the year since our last meeting, Ames had been busy developing Bored to Death with HBO producers and observing the transformation of his novel The Extra Man into a film. He was back in Iowa City to give a reading in support of his newly released graphic novel, The Alcoholic (written by Ames and drawn by Dean Haspiel). I met with Ames a few hours before his reading.

BLVR: What does it mean to make it as a writer?

JA: Being able to pay the rent. Getting a book out there. Consistently writing and being paid for it, I guess. Sure, you can write your whole life and get joy from it, or other people might read your stories. I guess I’m talking about publishing books and being able to support yourself as a writer. It’s very hard to do. Maybe you have to teach, but even then I just don’t know how many of my students actually have enough to write a whole book. On a sentence-by-sentence level almost all of them have talent. But who am I to say? I’m a middling writer. I’m not genius or super-talented, but, you know, I’m surviving. In the [Iowa Writers’] Workshop one girl wrote a really accomplished short story and everyone else attacked her, which I’ve seen happen before. They love to attack things that are actually on the next level.

It’s almost like that Vonnegut story: There’s this society where if you have a really good brain they’ll force you to have a radio in your ear that makes all this noise, and if you’re strong they’ll put weights on you. And there’s this guy with a clown nose, weights, and his hair is shaved and he’s got chains all over him because the whole culture’s gotta be mediocre. The TV announcers have lisps ’cause you don’t want someone who can really articulate themselves, because it’ll make people feel bad. And this man’s watching TV and he’s obviously a little bit intelligent, because he’s got this radio that goes off in his head anytime he might start thinking too much. His wife doesn’t have too many talents but she’s physically strong so she’s got a ten-pound bag around her. So this guy’s watching TV and there’s a ballet and the ballerinas are wearing masks if they’re too pretty, and if they’re too good they’ll have sandbags. Then this guy busts in who’s got the most covers: chains, clown things, piercings, anything to break his beauty and brilliance! And he rips it all off and he chooses the most beautiful ballerina and he rips off her sandbag. And they’re so amazing that they fly up to the sky, and the man watching this on TV realizes he’s seeing his son who has been taken away from him, and the radio in his head starts going off and he can’t even grasp what he’s seeing, and it’s on national TV, and that’s when the police come in and shoot him down. They had to shoot down the thing that was beautiful and great. And you can see it in our own culture. All of the assassinations…

BLVR: Reading your work—essays, novels, the whole thing—I notice that certain characters, scenes, and lines resurface, whether it’s fiction or nonfiction. I’m thinking specifically of that line your aunt says—“I love you more than you know”—which I’ve seen in essays, and then we see it in the graphic novel.

JA: There’s definitely a lot of blurriness, and there is definitely a lot of self-theft. Once I make things up, though, it’s definitely fiction. When I write the nonfiction I stick pretty close to the bone and I don’t make up events— though I might condense the order of things. Then, in the fiction, even when I’m repeating lines from the nonfiction, there’s still a lot made up. On the other hand, I don’t mind if it’s one big blur, because all of my books represent time periods of my life that I’m trying to make sense out of. Like a caveman scratching on the wall, we have this need to give witness to our lives and say, “This is what happened!” even though it gets completely forgotten and dusted over. I do like all of the blurring and stealing of my own lines. In The Alcoholic someone might also see some of the friendship issues that I wrote about in my first novel, I Pass Like Night. A lot of The Alcoholic gives visuals to scenes I wrote twenty years ago. But I also took that theme of fractured friendship into the next phase of life, which I Pass Like Night didn’t do. In particular, I addressed the real death of a friend, a guy who died of AIDS who I never saw again. In my TV show I have a character say a line from my novel The Extra Man. The actor playing Jonathan Ames (Jason Schwartzman) says to Ted Danson, “Do you think we drink too much?” And Ted Danson says, “No, I don’t think we do. Men face reality. Women don’t. That’s why men need to drink.” And then Schwartzman says, “Hey, that’s a line from my novel,” and Danson replies, “No, it’s not, you stole that line from me.” The bottom line is that it is a line from The Extra Man, and it was something that someone had said to me [in real life] that I put in the book.

BLVR: When you write, is there a very conscious effort to make a joke or to make an experience funny? Do you have to really craft the humor or do you feel it comes naturally?

JA: I don’t know if I go about crafting comedy any differently than I’d go about crafting anything else, but it’s about acknowledging something—like a neurotic thought I’ll have—knowing that it’s funny. It all comes down to storytelling rather than “How can I be funny right here?” Though TV is a little bit like that. They’ll say, “We need a funny line here.” It’s more definitive. In fiction, you’re not necessarily thinking that. In TV, you’re almost forcing the comedy.

BLVR: How do you feel about working in Hollywood these days?

JA: The movie they’re making of The Extra Man isn’t so much a Hollywood film. They’re using great actors [the stars are Kevin Kline and Paul Dano]. It’s an independent film. HBO [the studio behind the TV series], in terms of Hollywood, is good Hollywood. I feel kind of weird because the country is struggling more than ever—and I’ve basically been struggling my whole life, been living below the poverty line—but now I’m on the verge of perhaps doing really well because if the movie does get made, I’ll get some nice money for the rights to the book. If the TV show happens, I’ll get some nice money. I’m still scared about it all. I’ve been feeling a bit lost. Like: is this who I am? You know what I mean? My own little personal myth is changing, or could change.

BLVR: Your writing really explores the gray area of sexuality. How do you perceive sexuality?

JA: I will say this: My life has been dominated by sex. I think it’s the thing that most interests me. It’s where all sorts of weird psychological stuff gets played out. It’s where I engage in adventures and dramas. Other people develop deep and profound hobbies. They travel. They climb mountains. For me, a lot of my heroism has come in the shadows of life, some of which I’ve written about but most of which I haven’t. As much as it seems I’ve written about sex, I haven’t quite touched on it, really. It’s also annoying how dominant it can be. I mean, what is it? It’s our genitals and rubbing and fucking and sucking. Enough already. Who cares! For me, a lot of it does feel very psychological, and if you mix certain drugs with it, it becomes a whole weird thing. I know years ago—and I haven’t done this drug for a very long time—when I had smoked crack and combined it with sex, well, let’s just say ordinary sex or normal life is like a record and the needle goes around the record. When you combine crack with sexual behavior it’s like putting that needle in one spot and sticking in this one groove of playing something out in your brain. There’s some connection between your brain and sexuality and childhood and humiliation and power and self-loathing and affection. You know in the action movies when they say, “There’s the gun chest!” or they go into the weapons room? Sex is like a huge weapons room for the human psyche. Look, there’s the hand grenade. You can really waste your life on it, or it is your life.

III. MAY 2009, BROOKLYN, A CAFÉ

I spent a few days with Ames in New York. I watched him charm various editors and New York literati, and then met up with some of his crew, including the Mangina and Reverend Jen (author of Live Nude Elf). I also spent some time in Park Slope on the set of Bored to Death. He was central to the production, running from shotgun meetings with screenwriters to coaching actors in between takes. During this time, Ames was also prepping a new collection of essays and stories, called The Double Life Is Twice as Good.

BLVR: I’ve seen this notion that you have few friends, but thousands of acquaintances, come up in your writing a few times. It’s the idea that you’re this loner in the world. Do you really view yourself as a loner?

JA: I am a loner. Obviously, I do have friends. But I was happy to be alone last night. I had dinner by myself. It felt good to be in my own shoes. I went to a movie by myself. I was just happy to be alone. So yes, I am a loner. For example, all the people in these different places around town, like this café, the people know me. I go to the Russian baths and they know me there. But I am known in a very anonymous way, just from the repetition of going to a place again and again. There’s even a flop hotel—I won’t say why I’m there—but they know me. Then there’s a sushi place. They know me. It’s almost like I have these sign language friendships. It’s because I’m always alone in these places. I never come with other people.

BLVR: Are you at peace with the way you’re being represented in the new media you’re working in? Now there’s the visual and audio side of you: the television show and the movie.

JA: Ted Danson’s character [in Bored to Death] says to the young Jonathan Ames character [Jason Schwartzman], “We don’t really know each other. We’re in two movies. I’m in your movie and you’re in my movie. We just make guesses at knowing each other.” You know, anytime you express yourself, it’s not going to come out perfectly. If you do a handprint onto paper, not even that comes out completely right. Writing gets diluted too. A lot of times I look at things I’ve written and say, “You know what? That’s not what I meant”—or it was only half of what I meant, but a lot of times, half is good enough. With the movie and show there are the costumes, actors, lighting, and camera angles: all of that stuff can shift. A lot of times [the final product] certainly isn’t what I pictured in my mind, but it’s a pretty good approximation.

The Extra Man (film) was really weird for me because so much of that novel was autobiographical: exact scenarios that had been turned into fiction. It’s unlike Bored to Death, which is completely imagined. Yes, there might be little moments in Bored to Death—like I have Jason run his hands through an empty closet, which refers to an essay I wrote about my life after a girlfriend had moved out—but there is very little pure autobiographical stuff in Bored to Death. The Extra Man is very autobiographical. First, I lived that life, from ’92 to ’94. Then, basically, I tried to re-create it as fiction when I was writing the book. The book came out, and I read aloud from it for years. I even did an audio- book reading. Then, years later. I’m on set watching it being turned into a film. The layers were getting really interesting in terms of memory, because what did I really remember? When I first I fictionalized it in print I changed things. Then it was changing again on film and I had to ask myself, “Is that what really happened?”

Kevin Kline [who plays the character Henry Harrison] was like a profound fucking mimic, but he was doing a fictionalized version of a fictionalized version of what had once been real. When I wrote that book, I became addicted to the older man [the true-to-life person on which a central character from The Extra Man is based]. I loved him as a character. When I answered the phone from ’92 through ’94, I was like [in a spritely British accent], “Hallo!” My friends thought I was the guy. I learned a whole lot of rhythm from this guy.

Some scenes for the film were re-created right out of the novel. For example, I once escorted a lady to the Russian Tea Room and the director used the Russian Tea Room as the location. We sat at an old table where I had once helped an old lady drink champagne. Back in ’93, I was an escort. Then I was back in the Russian Tea Room watching that scene being re-created and filmed. They had me be an extra. It was very profound because there were three layers: there was the life, there was the fiction, and now this other level of fiction: a fiction of a fiction. I was like, “Oh my god, that’s how it really was,” or I’d see Paul Dano [who plays the young Jonathan Ames–esque narrator] capture my sexual torment back then with just one look on his face. They re-created a tranny club for another scene, and I played an extra with a line. I kiss this tranny in the scene, over and over—she has subsequently called me a number of times and I think she wants money and shit but I haven’t called her back, though she was very cute and you’ll see it in the movie—but the camera begins with me handing her a piece of jewelry and her just looking at me and I say, “I adore you,” and the camera comes up as I kiss her and then follows a waitress over to Paul Dano. For me, it was like my Bukowski moment in Barfly.

BLVR: In the beginning, how did you make it through New York being so poor? How did you make it through the writer’s life?

JA: I’ve always been a very frugal person. I don’t need a lot. I don’t have to live in a comfortable manner. I often stumbled upon cheap rents. It’s the typical New York thing: “I gotta deal!” From ’97 to ’99 I paid three hundred dollars a month and lived in the East Village. I never thought I would have made it to the East Village, because by the time I did it was already getting too expensive. Then this guy I met at an artist colony was moving out to L.A. to try to make it in the film business, and he had had a rent-controlled apartment since the early ’80s. That enabled me to live in the East Village right toward the end of the East Village. That’s when I was writing my column (for the New York Press), which was great because I could be right in the streets of Manhattan. That was, like, three hundred dollars a month, and then I’d be teaching at the Gotham Writers’ Workshop two or three times a week. You’d get ninety bucks for a class. It was fucking slave labor. It was, like, three hours plus a shitload of reading. But I’d do two or three of those a week, so that’d be, like, two seventy a week. I was reading literally two hundred pages of amateur fiction a week, and I think I also still taught composition sometimes at a business school in Manhattan. A couple of times these students really liked me at Gotham. It was this core of women, so I started my own private class with them, which I wasn’t supposed to do. Then I always liked to perform at night so I’d set up these shows at the Fez and make two hundred to three hundred dollars a night. You know, once a month, we’d do a big show and I’d pay everybody and keep three hundred dollars for me. I also had my son. I’d get in credit-card debt that would range between ten and twenty-five thousand dollars depending if I had to live off a card. I fell into that semi-Ponzi scheme of getting a card to pay off another card. You know, I had loans from Columbia [where Ames went to grad school] to pay off. I don’t know, I just hustled and hung in there. I didn’t really have any other skills. Then things would come along right when I thought, Fuck, am I going to have to borrow money from my parents again or, worse, move home with my parents? I was at one of those awful moments in my life, when someone dropped out of a teaching job at Indiana University. So I went and taught there from 2000 to 2001. I love reading Bukowski. I recently bought this book of his collected weird essays or something, a lot of which talk about the writer’s life. A lot of what he talks about is fucking perseverance. You just hang in there. I would do that Woody Allen thing of “just showing up.”

BLVR: What happened in that nine-year gap between your first and second books?

JA: Well, I just really struggled. I had to go through purgatory. I had to actually learn how to write. Teaching composition really helped me. I had to study grammar so I could teach grammar, and then my writing went to a whole other level. I’m not a great grammarian now. I am not a sentence architect on a high, profound, three-dimensional chess level, but I got a better grasp of the sentence, which I never had. My first novel is full of run-on sentences, but to me they seemed like sentences. I remember the editor saying, “I love your use of run-on sentences. It captures the voice!” and I just nodded my head and said, “Yeah.” I never understood the math of writing until I taught composition. So while I was teaching, I struggled to find something to say, to write about. Then I met that man I lived with who became the idea behind The Extra Man.

Columbia. He was leading a three-day seminar and said that in his experience he had rushed out his third book because he was “a good dog when published, a bad dog when not published.” He realized he just had to find something he was in love with and not just write to be published. That’s what had been going on with me from ’89 to ’92. I was trying to write a novel just to be published again. I was like a rat in a cocaine maze. I just wanted the high of having a book and not actually writing one, because something was deeply motivating me. Price said these things— good dog, bad dog, and finding something you’re in love with, and he also said that writers hang out. I chased him down the street and said, “Thank you so much for what you said. That’s how I’ve been living the last three years: writing another book just to write another book.” He said, “Maybe you should just stop trying for a while and drop out.” I said, “I can’t drop out, I just signed all of these loans.” And he said, “Do you like cops?” Because that’s what turned around his writing. He had been put on assignment for something else and had to hang around cops. He loved their language and took off from there. So I thought to myself, What do I really like? I realized I liked boxing and trannies.

I started going to this gym on Fortieth and Eighth Avenue when Times Square was still Times Square. And there was this tranny bar right across from the New York Times. I’d go box and then I’d go to the tranny bar. In both places I was around young men looking in the mirror at themselves. One was this heightened masculine version, and in the other they were being women. Both worlds were very different. The boxing gym was all black, Hispanic, and Asian, and the tranny bar was all black, Hispanic, and Asian. I had come from the world of Princeton, so these were very interesting places for me in terms of trying to find out who you are and in terms of understanding economic levels. I would leave the gym and go to the tranny bar and kind of do what you’re doing now. Sometimes I even had a tape recorder. I was interviewing the trannies because of my own interesting sexual journey. I was doing research. I spent ten years in tranny bars. I loved the drama, the comedy, the tragedy, the masquerade, and the circus nature of it. That’s why I say I’m a loner. No one from my world would come with me to these places. The deepest, longest hours of my life have always been alone with strangers.

Slowly, I realized I was more intrigued by the trannies than the boxers, and then that I was most intrigued by the old dude I was living with. So I wrote the first chapter of The Extra Man about the guy and this old tranny I had met. I lived that life and worked for years on that book and started performing and teaching composition and just kind of went into an apprenticeship of writing.

That was one question, really: how’d you make it? Well, I hung in there. So I can’t fuck up this HBO thing. I wouldn’t mind retiring and teaching someplace like Iowa. I liked it there. I’ll try that life at some point. I hope I can keep making it. You never want to go back to moving in with your parents.