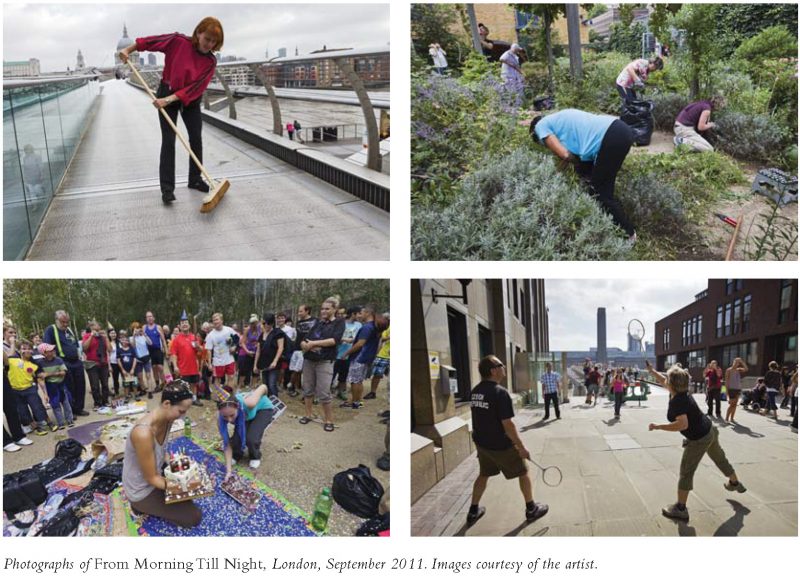

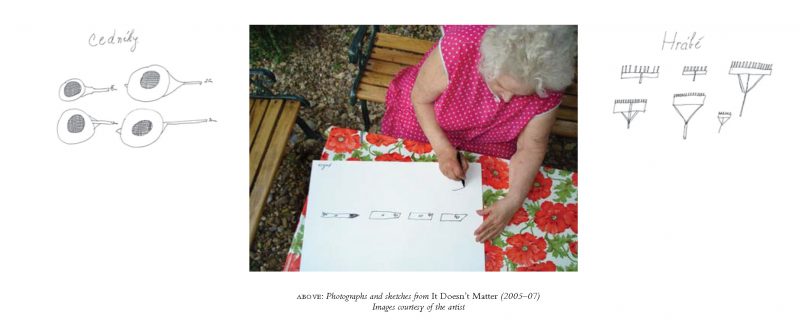

Kateřina Šedá is a thirty-four-year-old Czech artist, living in her birth village and collaborating with nonartists living in smaller villages in her country, intervening in their social circumstances to generate actions that yield atypical social configurations. For There Is Nothing There (2003), she studied the daily activities of the citizens of Ponětovice, a small Czech village, and then rearranged their schedules, synchronizing the entire village so their quotidian and usually isolated activities happened together. The town council participated, and turned off the lights at 10 p.m. Many of her projects involve large groups of people and complicated logistics: From Morning Till Night (2011) featured eighty people from Bedřichovice, Czech Republic, who traveled to London, where they occupied an area identical in scale to their village. They went about their ordinary activities while eighty British painters surrounded the performance, painting a representation of the village from photographs. The boundary between Šedá’s life and her work is permeable to the point of disappearing entirely. With It Doesn’t Matter (2005–07), she goaded her depressed, bedridden grandmother into creating six hundred drawings based on the inventory of a home-supply store her grandmother had worked at her entire life.

Šedá laughs a lot at herself, and easily acknowledges that even she has a hard time explaining her projects. She speaks quickly and forcefully, sounding like a Hollywood depiction of an Eastern European revolutionary, and expresses bemused and resigned impatience with people who do not understand her idiosyncratic epiphanies. For the first part of this interview, she spoke through an interpreter, who eventually left her on her own.

—Darren O’Donnell

I. THE PROBLEM WITH ART

THE BELIEVER: How did you arrive at this kind of work? When you were eight years old, were you thinking, I want to fuck with people’s heads?

KATERINA ŠEDÁ: This came from childhood; when I was a little girl I always tried to control other children. When they asked me what I would like to do for a living, I always told them I would like to be a director. They asked me, “Director of what?” and I told them, “Well, director of everything.” I understood my classmates’ actual roles in society: who would calm the group, who should not be present at certain points. I always had the feeling that this was my future profession. This is how I perceive my current occupation; it’s almost a calling. In Czech the words for occupation and calling are very similar. So for me it was very easy; I never made any decisions, it was a straightforward route. I’ve been doing the same thing I’ve been doing since I was a child.

BLVR: Did you study art?

KS: Yes.

BLVR: Why not theater?

KS: My big problem was that I was a very mediocre child. My last name means “gray,” and I was very gray. I did not really have any talents. I did not have a talent for music, or dancing, or, at that point, for drawing or painting. Since I was a small child, I was really fascinated by how I was able to put people together who were really not interested in being together. The bottom line is that I really don’t have a profession; I really don’t have any skills. I don’t have a driver’s license, I don’t know how to use a computer, and I don’t play any instruments. I am, for all intents and purposes, useless. All my life I understood that I have to take my mediocrity and turn it into an asset. This is the opposite of people who are considered outstanding because of their special characteristics. My effort has always been to become outstanding because of my mediocrity.

BLVR: At what point did you decide—

KS: To go to art school?

BLVR: To do something that you considered a project?

KS: I never call them “projects.” The curators call them “projects.” I call them something different.

BLVR: What do you call them?

KS: Zázrak!

BLVR: Zázrak?

KS: “Miracle,” basically.

BLVR: [Laughs]

KS: Zjevení.

TRANSLATOR: Oh my god, zjevení. [Laughs] “Epiphany.”

KS: Zahájení.

TRANSLATOR: “Opening.”

KS: Uzavírací.

TRANSLATOR: “Closing.”

KS: I would go so low as to call them a “production.” I hate “project.” A project is to go to the toilet. I hate it. When I reached eighth grade, I had been drawing a lot, and I always drew things that I was interested in. They weren’t great drawings; they were drawings about my thoughts. When I was twelve I was making sketches to replace the TV set in our house. Fifteen years later, I realized that this could be considered a type of conceptual art. I met this teacher of art, and she suggested that I could go to an art school and continue in this field. The portfolio that I submitted included an instruction book about how to clean your nose, and a project called Throwing Peas Against the Wall, in which I did drawings with an iron on sheets. There is a saying in Czech that if you are engaged in a discussion with somebody who is absolutely inaccessible and disinterested, it is as if you are throwing peas against the wall. When I applied for art school, they asked me, “Are the sheets that you peed on all you are doing?” because it didn’t really look like much.

BLVR: Did you really pee on sheets?

KS: No, it was the iron, but it was so ugly.

TRANSLATOR: It was probably yellow.

KS: I had one teacher who was a very good artist. He was in Documenta 10. He’s a very good painter, but after Documenta 10 he decided not to continue in the big club of art. He’s an amazing person, and he saw me as exceptional because I was very different, and that’s why they accepted me.

II. THE PROBLEM WITH THE WORLD

BLVR: You talk about wanting to instigate change. What kind of change are you trying to instigate?

KS: The change that I am seeking is a change in real life, in the real environment that is the subject matter of my art. I had this project about my grandmother, who had lain down and refused to move or to do anything. The first change I was seeking was to make her change her behavior. There were a lot of people who were critical of the drawings that my grandmother made, saying, “Why didn’t you use better paper, better pencils or pens?,” but they didn’t understand that the first objective was not the drawings—the same way that There Is Nothing There was meant to change the villagers’ perception of their village. They had been saying, “There is nothing there,” and I wanted to change that; I wanted them to understand that there was something there and they could do something about it.

BLVR: Are you interested in changing things to make them better? Do you take a normative or ethical standpoint? Are you trying to do good?

KS: People laugh at me and tell me that I am naive. I am very optimistic. Optimism is something that is in short supply in the Czech Republic, because we’re still looking at the totalitarian regime. The other topic is trust. Trust is in short supply, because people don’t trust the politicians; they don’t even trust the other people. They don’t even trust you when you tell them that they are going to get something for free. When they do get something for free, they really don’t know how to handle it. When this happens, these people are almost in a new world. That’s why various political parties approached me and asked me to work with them. They see that I can persuade a large group of people, and these people do trust me. The trick is that I’m able to persuade them because I am in the same position as they are. I can never elevate myself above these people I work with in the villages, because at that point I would be finished. In There Is Nothing There, the people did ask me, at the end, if I would like to run for the office of mayor in the village, because they finally saw somebody who was interested in them. But that definitely must never happen to me—I could never do that, because that would be the end of it.

BLVR: Do you become friends with these people?

KS: Yeah, a lot.

BLVR: Do they come into your life? Do they come into your house? Do you send them messages: “Hi, I’m in New York”?

KS: It’s very different for each project. Some of the people I am in contact with, and with some it goes away. The overall atmosphere actually changed over the last couple of years, because in the past people were more afraid of me, and now I am actually getting approached by them.

BLVR: Do they know you are in New York showing photos of them to auditoriums filled with people?

KS: There Is Nothing There is special and a little difficult because it took me a very long time to persuade them to do it, and this aftertaste stayed with me after the project. There was this other project where I took these people to London, and they’re much more interested in it, and they are following me here in New York. I can’t really generalize.

BLVR: What was the project in London?

KS: It was a rather specific project called From Morning Till Night that I based on the fact that most of the villages of the Czech Republic become deserted in the morning—there is nobody there—and everybody comes back home at night. I was thinking about how to arrange it so the daylight would not be so separate. I was thinking about how to remove the separation among the people without them returning back to the town. For that reason, I took the village and brought it to London. I selected a church that was close to the Tate Modern, which served as a reference point that corresponded to the church in the village. Because this was supposed to be a miracle, I needed the village to appear there.

So I contacted about eighty British painters, who were positioned around the imaginary village in London. They painted the village, which was not there. Part of the performance was that these painters would be absolutely behaving as if they were seeing the village, and they would be informing the bystanders that they did see what they were painting. To prepare, they received a photograph of the village from that particular perspective, and used the photo as the reference for their painting. The spectators probably thought that they had lost it.

The people that I brought from the actual village brought life to the whole picture. My idea was that the participants, the people from the village, would see the village in a very different light, and see themselves in a different light. They’re supposed to do the same things that they would normally do on a regular day. We had a professional interpreter who lives in the village, and she organized a lesson on the Czech language in the church, and she would work as a tour guide for the British spectators. It was pretty amazing to see her walking with a bunch of British people and telling them, “Here you see a building from 1925,” and everybody was looking at nothing. Practically all the people I brought there from the Czech Republic—eighty people—said it was the best weekend of their lives.

BLVR: [At this point, the translator has to leave, and I’m alone with Katerina. She struggles, but does a fine job speaking English.]

III. THE PROBLEM WITH MONEY

BLVR: How would you describe your relationship to the global art world? It doesn’t quite seem “suspicious,” but it seems—I mean, why bother to show work?

KS: For eleven years, I didn’t have a clue about how to raise money for this kind of work. I was very poor; my parents are uneducated, and after school I thought that I wouldn’t be able to continue, that it was impossible in my country. I have a very good gallerist, Franco Soffiantino, from Italy. I was nobody—I was person zero, and he believed in me, but he never thought that I would become successful; he contributed money because he loved this kind of work. He asked me how much money I wanted for a project. I had made everything for free, so I didn’t know, and he asked if five thousand euros was enough. I had never seen that kind of money in my whole life. I said, “Wow,” took it, and slept with it. In the morning, I realized it was true. Because I live a very simple life, I was able to live off this money for two years. I’m a very bad artist for the market, because I insist on keeping my work together. Projects can take one or two years and can have hundreds—thousands—of elements. I have a lot of people who want to buy them, but piece by piece. The gallerist pushes me, but I never say yes, because it’s impossible to divide my grandmother’s show, for example. I understand perfectly; it’s really difficult to sell these pieces, it’s extremely expensive for production, but I don’t know what else to do to continue. If I don’t find any more money, I won’t do another show. For me, it’s not so important. It’s more interesting to make my village famous, and people from all over will come to the village and not to the galleries. I would love to be rich. I’m so tired of traveling place to place, showing in exhibitions because I’m not a good artist.

BLVR: The French sociologists Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello talk about the need to criticize the very mobile lifestyle that characterizes many of those who are considered successful in the field of art.

KS: I really want to spend my time in my village, but I need to find money for this place. In my country, they tell me that this is local art, and they don’t give me money. If I want to work with this place and change the place, I need money. Generally, with respect to money, I’m very poor. I don’t have a car. I don’t have a flat. A lot of people see a lot of money in my work. We go to London—it’s the most expensive destination, but after each project is a big book, which I must fund.

BLVR: Do you have a day job now?

KS: No, I work only on this.

BLVR: Is most of your day sending emails or knocking on doors or…?

KS: I have a baby now, so I work in a crazy way, but generally I’m very often on the terrain with the people. I hate emails; a lot of people spend half the day with emails. Me too, but I try to be out, usually speaking with the people. I would prefer to spend eight hours in shops, speaking with the people. When I made the project with the village, I spoke with the people in the village every day for eight or ten hours. Some people are allergic to considering this a “job.” There is the feeling that art is something special, something incredible. A Czech curator told me, “A job? It’s not a job; you look like you’re going to the company, working.” But it’s true; it is a job, it’s really hard sometimes. It’s psychological work. You must think all the time, and I’m so tired.

BLVR: Do you consider yourself an activist?

KS: No. No.

BLVR: Why not?

KS: Because activists—I don’t know how to say it in English—they don’t agree with anybody. Usually I feel more like a child. I don’t like to be an artist, either; my job is different. In each project it’s different. So, for example, in my project Over and Over, at first I was a hole, and, after, I was a key—

BLVR: I’m sorry, you were what?

KS: A hole—this is not a job, this is not a person; it’s like an object. But I was this object. I was a hole because I needed people to see each other through me.

BLVR: Oh, a hole!

KS: And, after, I was a key, because I connected the people. And in There Is Nothing There, I was, at first—I don’t know how to say it in English—something in the middle. After, I was a friend. After, I was an observer. After, I was a child. I changed a million times. For my grandmother, I was a granddaughter. I was never an artist. To say “artist” or “activist” is just stupid; it’s not precise. So with my grandmother I’m a granddaughter, and I want all the granddaughters in my country to see what they can do. If I’m an artist, they would say, “OK, this is an artist’s work.” But when I say I’m a granddaughter, they have a feeling that it’s very ordinary and they can do it. It is the same with the village. If I say, “I am a friend,” they say, “OK, she’s a friend.” If I say I’m an artist, then they feel it’s something special. I want everybody to feel that it’s a very ordinary situation. So I’m afraid to say it’s art, because in my country, art is something very special—to be an artist and do art. I never use this word when I work with the people. I must find a new reason to explain to the people, and must find my own roles, my job.

IV. THE PROBLEM WITH PEOPLE

BLVR: Do you use the word collaborators to describe the people you work with?

KS: This is a really good question, because my job is always different and their job is always different, too. I don’t say “my actors.” Well, sometimes I do. Sometimes they are like tools; sometimes I’m a tool. Usually when I say it was successful, it’s not after the action when everything goes well. It’s the point when I realize what I must do. Sometimes I must disappear. Sometimes I disappear in the middle of the action, and they try to find me, and I’m lost because I see I’m not important now. When I realize my role, I recognize it was successful. It’s really important to find what I do, and find the same for the people. Like I said before, that feeling in elementary school when I knew what everybody must do.

BLVR: You see people’s untapped strengths.

KS: Yes. For example, in London, somebody who sweeps for their job, sweeping is only the visible aspect. The most important aspect is what is between the people. One woman was only sitting quietly, and some people told me that she’s usually really noisy. But this is her real job, in my opinion, because she looks like a very quiet person. My assistant said, “She doesn’t collaborate in the action, you must push her for some activity.” But this is her activity. Everybody asked me, “Where is she?” They tried to find her. It’s important to recognize that this is not the main point: everybody in the village sweeping together, the village being moved to London. The main point is to find the real jobs for people—their real vocation.

BLVR: Do you have to be a bit of a therapist? Do people get scared or confused? Do the projects trigger feelings that are not part of the projects?

KS: Yeah, yeah. I’m really very dry after the work, very tired. It’s strange, because I’m a very emotional person, and when they have some problems, I think about it and I try to speak about this, but at a certain point, I have to stop and only continue with the work, otherwise it would not be possible to finish the work. When you bring eighty people to London, there are many practical problems: one is ill, one is tired, another person wants this, and another wants that.

BLVR: Is overcoming the practical problems part of the artwork?

KS: Until 2009, I did everything myself. Since 2009, I’ve had two assistants, because I made a very difficult project in which I invited 511 painters to create a profile of my village. So my assistants had to call every day to find the artists; it was impossible for only me to do it. One of the assistants had to care for the people, but unfortunately it’s really difficult to find a good assistant in my country. My photographer told me that I’m so strong and so… I don’t know… it’s very difficult to follow me. In the last two years, I’ve had maybe fifteen assistants.

BLVR: Wow, fifteen assistants. What is their background?

KS: I started with high-school students, but now I work with some older women. It’s really difficult because I’m usually looking for some person like me, and it’s impossible to find. Some people are good for practical things but they are not so good at speaking with the people. Another person might be good at speaking with the people but they make a complete mess of the work. I need a complex person who is very honest, so people will believe her, someone who is older. I tried to make a combination with two people, with three people; it’s like a whole other social project. [Laughs] I found two good assistants. Each had something different: one was good for the people, one was good for the artists, but they hated each other. We were in London, and one assistant had damaged luggage, and I said, “OK, I will pay you for the luggage, we can go.” We had eighty people waiting in the bus, and my assistant said, “But I need my luggage.” So I said, “OK, you will stay here. Bye.” Sometimes they’re lazy, sometimes not too much logic, sometimes they cannot recognize the main point. I have a small group of people: a graphic designer, a writer, and a photographer who work with me. All men. They work very hard, not sleeping, but it’s very difficult to find an assistant for practical things.

There’s also a practical aspect that necessitates my presence. Because I am the main person, when my energy is lost, they lose faith. I must constantly keep an eye on people’s energy. I think about it in terms of a gradation from light to dark gray. The action happens when the energy is in the middle gray. When I see them riding in the bus and their energy drops, I know the danger point. At first they start to touch their hair—I know exactly what they do— and after that, they wring their hands. My assistant said, “You are an idiot, you’re crazy.” I know this from eleven years of experience. I know exactly—then they will do this [touches her face]. I must do something: sing, or push my assistant to do something. The participants don’t know that their focus is dissipating, they don’t recognize it, they just get distracted and say, “Oh, I must go to my luggage,” or something else, and then eighty people start to get up and find things to do to amuse themselves, and their focus and energy are lost. My photographer told me, “Katerˇina, it’s impossible that somebody else will understand this,” and I said, “OK, you must follow me.” When I see the group’s energy go down, it’s really difficult, because eighty people—it’s too much. One person can kill the energy. Finding the performers is easy; finding assistants is difficult.

BLVR: Have any of the participants you’ve worked with wanted to create more work with you?

KS: After the project in London, the people called me and said, “Please do something this Sunday.” They call me a lot, which is really strange; it’s happened before, but not so intensively.

BLVR: Will you do something with them?

KS: Yes, we’ve continued for five years. But they want more and more, each week. They need someone to facilitate a connection between them, and they think I am kind of in the middle. But I need to find money to continue. Connections are expensive. I made a project with a thousand families in a housing development in the Czech Republic. It’s really important. In the 1970s, when they made these apartments, each was occupied by different groups of people who came from the same area in the country, and all the apartments were painted gray. After 1989, the people started a regeneration and painted each apartment a different color. But it’s really strange because it was a new pattern for this place, because each apartment was painted to look like a different place, where these people had come from.

I had the idea to connect the people through this pattern. I asked the architects for the sketch of the apartments, and, based on this design, I made some shirts. But the main point was not the shirts; that wasn’t the art. Instead, I created an invisible person to connect the people. The project must be secret. I wanted to connect a thousand families. So I coupled up a family from this building together with a family from that building, and one from this building with one from another building. Then one day I sent these thousand shirts in the mail, the return address on the envelope suggesting that these families had sent them to each other. There was no accompanying information, just the shirts. People hated this project. [Laughs] It was really funny, because a lot of families called each other and went together to the main building and said, “We don’t want these shirts, what is this?” After a month, I sent invitations to an exhibition. There has been no further collaboration with these people, but this project was successful because, for example, one couple fell in love, neighbors who had lived there for thirty years finally met. But people can’t recognize this; they meet with the other family at a restaurant and then together they come to me and say they did not connect. But they did!

BLVR: Do you care if they make friends and fall in love?

KS: Yes, I care, but not about everyone, because it’s impossible. I’ve made many works with a lot of people over the last two years, and it’s not possible to follow everyone. But what I can do, I do.

BLVR: Do people want to work with you because they think you can improve their lives?

KS: Yeah, yeah. I have a queue of people who want to do something. Very often I work with another group of people, but sometimes I work with the same people and change something in one place. Sometimes I work with one group for one year, or five years, but sometimes they hate me at the end. The rules are very open. I don’t know what will happen in the end. Each work is different.

When I made the work with my grandmother, I had to sit with her for five hours. When I went to the toilet, my grandmother would very quickly go to the bed and sleep. People wanted to believe that I said, “Grandmother, please, draw six hundred drawings,” and she just did it. It’s complete nonsense. My grandmother would draw only if I was with her and speaking to her. This work is extremely difficult. All the drawings that were displayed were made when I was with her. This is the main point. I showed one video in which I really strongly pushed my grandmother, and some curators wrote that I’m a big manipulator. But it’s not true; you must be in my family to understand, because my grandmother was a really big problem. She was not ill, but she decided to only lie on her bed and cry. This destroyed my family. My father and mother are good people, so they felt they had to stay at home and take care of her. I had to do the same thing. This caused big conflicts. She is very lazy. We had to sit with her: “Grandmother, can you please get up?” “No, I like being on the bed.” It looks like a nice story about a nice grandmother and a nice granddaughter, but it’s not true. Some stupid curator wrote something like this and never asked me.

It’s much more honest to show this to the public, not show this romantic story, because it’s not a romantic story. It’s a story about a grandmother who was so lazy and the people around her who were so unhappy. I think it was really important to show this: “Please, Grandmother, do this.” Without this push she would never have done anything. In the end, she was happy, too. It’s really important to portray this process. Without this, the project disappears. Of course, if somebody wants to call me a manipulator, they can, but the people who work with me never say this. The people from the village, my family, my grandmother—nobody says this, it’s people from outside. Of course I can show this romantic story, it’ll be so nice and all the women in the shops will cry, but it’s not true.

It’s really an important point that I changed this really lazy person, and not only her, but also I changed my family. My mother was crying, saying that my grandmother was a stupid person, because my mother had to clean her room. But when my grandmother starting drawing, my mother said, “OK, if she can draw, I can clean.”