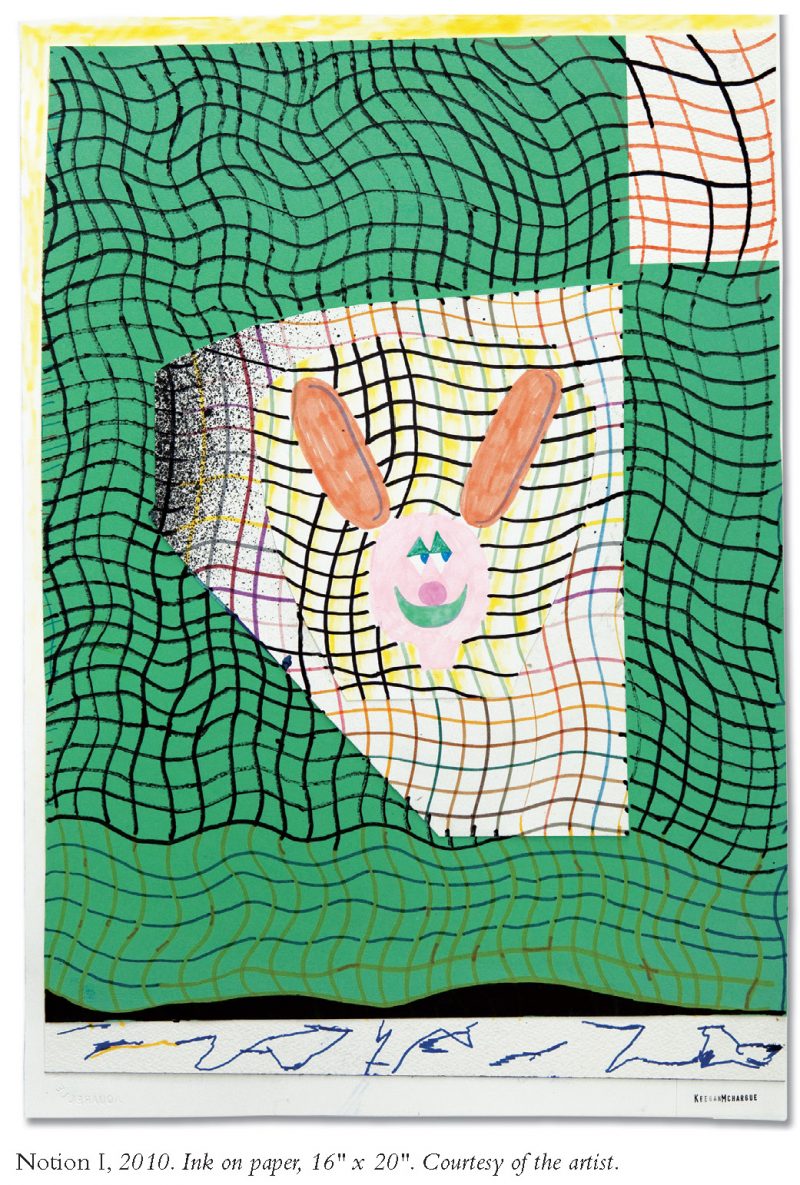

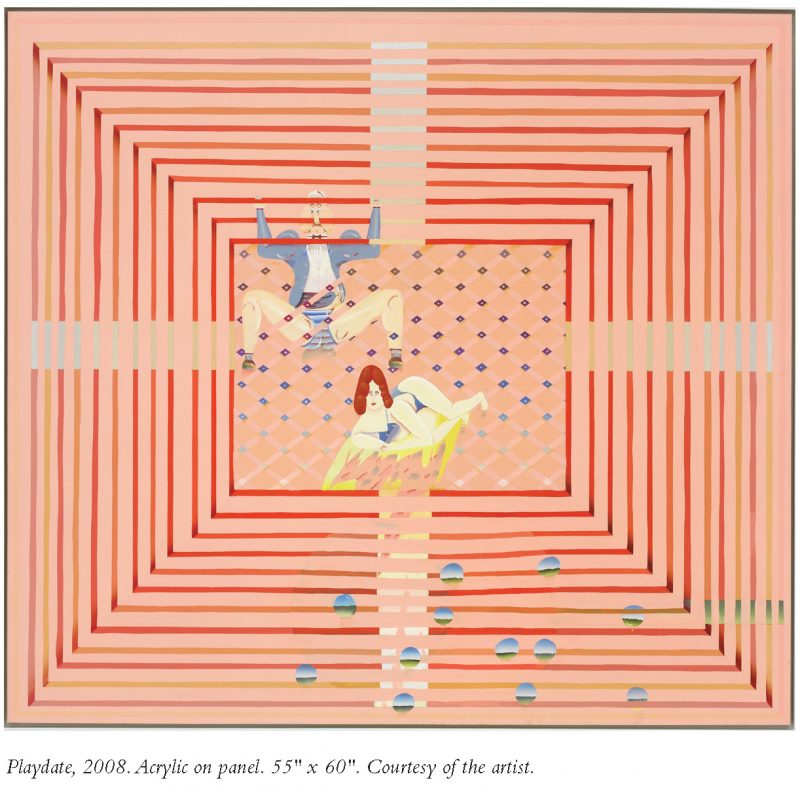

In their own playful way, the paintings of Keegan McHargue tug at the very nature of perception. If M.C. Escher created his optical illusions through hyper-dimensionality, McHargue’s optical magic comes from a strikingly flat universe, a place where foreground and background are irrelevant, and the eye is drawn to nowhere and everywhere at once.

McHargue’s early figurative work suggests everything from Islamic mythology to comic books—art forms that overflow with symbolic narratives and cry out to be visually “read.” But where a papyrus or religious tableau can be deconstructed and understood, McHargue’s symbology of fat lips and piñata heads operates on the level of the subconscious, forever insinuating, never explaining.

McHargue’s recent drawings and sculptures regurgitate and revivify the vocabulary of design—corporate logos, punk-rock fonts, and tablecloths—with an obsessive child’s attention to detailed, artisanal patterns. Though the word decorative has become synonymous with unengaged art, McHargue engages with decorative thinking itself, placing the figure and ornament on equal levels of his visual hierarchy. In this way, his work is an expression of his worldview, in which impartiality and ambiguity are favored over opinions and clarity. Meaning is replaced by labyrinthine disorientation.

McHargue’s paintings show around the world, from Jack Hanley Gallery in San Francisco to Hiromi Yoshii Gallery in Tokyo to Deitch Projects in New York, and his work is currently held in the collections of the Greek art collector Dakis Joannou and the Museum of Modern Art. The following interview took place in McHargue’s studio, an old classroom in a defunct Catholic school in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Also a musician, McHargue played an ambient remix he had recently completed as he spread his newest series of drawings across the floor and toured me through his first experiments in sculpture.

—Ross Simonini

I. THE SURFACE

THE BELIEVER: Is that sculpture made out of chocolate?

KEEGAN McHARGUE: It is. I like the idea of sculpture as both art and product. Until recently, these two things had always seemed opposed to me. I want to create sculptures in “lines”—as in, fashion lines. This series of sculptures belongs to my first collection. They’re all the same size. They’re not intended to be overwhelming. They’re not sculptures that force the viewer into submission through physical dominance. I don’t want to force people into submission—I’m a pacifist. I want to make modesty.

BLVR: I want to take a bite out of it.

KM: That’s great. I want juicy work. The object should hold the power to possess its viewer. Two big interests of mine are consumption and desire. I’m really trying to discuss the idea of our collective desires. But I know for myself I am discussing the idea of sexuality more than I am discussing my own sexuality. I feel very removed personally from the sculptures, almost as if, through these artworks, I’m reporting anonymously about much larger conditions—the desire we have to take a big bite out of something. Though I guess you have to believe that people are just going to see you coming though the work, unless otherwise specified. It’s just a natural default.

BLVR: Where do these objects come from?

KM: I buy them. I love to shop. You’ll find me at the pet-supply store, the equestrian spot, the dollar store, with a big smile on my face. Consumption is a huge part of the work. Plus, I enjoy the idea that people are trying to sell something to me, which I will in turn try to sell to someone else. It makes me feel connected to a larger cycle.

BLVR: It doesn’t feel oppressive to you to have a company shove their product in your face?

KM: I’m a smart and competent enough person to make choices on my own, but sometimes it’s nice to have someone make choices for you. You don’t have to think. Some people are really good at advertising, and I want to respect that and buy something from them. Someone asked me once: would you rather live in a world with or without advertising? I picked “with.” I enjoy the stimulation that much. I grew up with punk ideals, so naturally I didn’t always feel this way. But there’s beauty to be found in advertising. It’s just too easy to shit on it as a whole—that’s a cliché. There’s a lot that can be learned from advertisements. I love the language of advertising. Artists like Jeff Koons and the pop artists knew that—maybe it was looking at them that did it, but at some point I proudly called myself a consumer. I am consuming information and regurgitating it in my art, physically and conceptually.

BLVR: You were saying earlier that you want to work in advertising.

KM: I guess I just love beautiful things and want to work with them. It’s like remixing—I think I would like working with other people’s objects in the same way I am treating ready-made products in my sculpture. I would love to make textiles and design objects for mass consumption. Sometimes I feel like an artist’s ideas can be spread more broadly through anonymous channels. I like the anonymity of advertising, the ability to play with reverberations in culture without claiming anything. It’s an illusion to think art doesn’t operate on the same level as advertising.

BLVR: Just different ways of seeing what makes people’s knees jerk.

KM: I’ve been learning about Edward Bernays. He was Sigmund Freud’s nephew. He took all of Freud’s writings on psychoanalysis and the nature of the grotesque—all those thoughts about how people’s limits are pushed, what draws people to objects, how people come to embrace things that are actually repellent to them. I love that. It’s a huge influence on my personal thinking, philosophically, and of course in my work as an artist as well—the psychology of desire. Questions like: How do you make people want? How do we construct our personality into an image that we project into the world? How do we sell concepts to others?

BLVR: And advertising doesn’t necessarily have to be nefarious.

KM: But maybe I want to use it in nefarious ways.

BLVR: Is that right?

KM: I’m not closed off to it. I want to push limits, and I can’t control what happens to something when it leaves my studio. Brands are exciting—whether they’re nefarious or not. Artists are more or less brands. Bands are brands.

BLVR: Obama is one of the best brands around.

KM: I loved watching Obama make his brand. I love watching corporate brands change over time, too, changing their logo from a bold typeface to a fine typeface. WalMart just changed their logo. People started saying, “Oh my god, these Wal-Mart people are evil.” How did they confront that? They changed their typeface. You don’t even have to touch what’s happening beneath the surface. All people care about is the surface. It’s all about surface.

BLVR: But real life doesn’t have a surface. It’s more complex than that. Or is it not? I mean, would you say that you get more from watching a bicycle race or looking at a painting of a bicycle race?

KM: Well, looking at everything through your own lens can get tiring. It’s limited. Maybe you want to look through someone else’s lens for a change. Sometimes you want to relinquish that power of the experience and accept things in a very clean, crisp, reduced way. You certainly miss something in a representation rather than an experience, but I’m not sure if one is more valuable than the other. Having both is preferable. Like seeing an event unfold in person and then reading about it in the paper the next day. It can teach you a lot about the infinite possibilities of perception. I know it is possible for me to get a richer—but perhaps limited—experience from looking at a painting or reading a story about something than actually experiencing it. Sometimes I opt for the limited.

BLVR: In some ways that seems like the only answer an artist can give. The whole reason for producing the painting or the book is to create a singular thing to comprehend, rather than the entire messy world.

KM: Sometimes you have to limit the window you’re looking through to get a clearer picture of what is you are viewing.

II. THE LEPRECHAUN

BLVR: Your new drawings are called the Preteen series. Why is that?

KM: I went from being a kid to an adult very quickly. I was watching cartoons one day and the next I was out on my own. I left high school at sixteen and jumped right into “life,” but there was a lot that I guess I just spaced out on. I never once went to a school dance, for instance. I missed all that stuff.

BLVR: On purpose?

KM: Yeah. As a teenager, all I cared about was art and music. It never crossed my mind to want to go to a dance or be social. But now I really like looking at what the kids are into. I like watching the Disney Channel. I like to watch TV and imagine who the commercials are geared toward, and of course who is being catered to. Those two things—which can be very different—are distinct because the commercials are for kids, but really they’re for the kids to convince their parents to buy the product. These are products being sold to people who don’t have any money of their own to buy them with. It’s an exercise in power, but a real covert kind of power, and that’s where I get into it with the Preteen series. Art isn’t free from that power, and certainly this series is about these distinctions in a very direct way. With Preteen, I am playing with the idea that a body of work can have multiple target audiences simultaneously by using some of the ideas of desire we were speaking about.

BLVR: The Disney Channel has its own brand of surreality.

KM: It’s completely disengaged from the real world. Do you watch The Suite Life of Zack & Cody? They’re on a boat now. You’re stuck in this world with these kids…. I made a show at Jack Hanley gallery a few years ago called The Yellow Spectrum. I tried to cater the show to babies. I hung the work low. I painted the floors bright and I used colors I thought babies might like. At the time I didn’t know yet that babies recognize red, primarily. It was my own homespun idea about what babies see. I was thinking about the sun a lot at that time and primary colors. Now I’m advancing to making work for tweens.

BLVR: Do you like cartoons?

KM: I don’t like the look of many cartoons, but I like what they represent and how they influence young minds. I am drawn to this idea of sugarcoating as a way to make complex ideas super-palatable and easily absorbable. One can perhaps spread concepts more broadly by planting a seed early and allowing thoughts to grow around them. Since the advent of TV and early cartoons, it would be difficult to calculate exactly how large of a cultural effect they have had on generations of people’s thinking—thinking that extends out into the real world. Cartoons have convinced us of so much without our realizing it. Some ideas are communicated well in cartoon form. I, however, don’t have too many grand ideas to plant, and my work isn’t even really catering to the same viewers as cartoons, even if I use some of the same devices. I mean, I’m not trying to make some bold point in my work. I’m just trying to play with imagery— cartoons can be good for that.

BLVR: Cartoons and comics are full of repetition, and a lot of the artists who work with cartoon vocabulary repeat their imagery. Philip Guston did this. Carroll Dunham does this. You definitely do this.

KM: Repetition is so comforting to people. It is relaxing to know what lies ahead. You liked it once, chances are high that you will like it again and again. But for me, I guess I’m regurgitating images and symbols repeatedly into work because I didn’t work through them the first time around. Who knows why these certain images take on such meaning to me? It’s fervor. I’ll get obsessed with a shape and it becomes all I can think about. Oftentimes I find that it’s not even a shape that I am particularly fond of. I don’t feel like I need to like it. I feel like I need to work through it to grow. Repetition can help in that. My work is not just a catalog of my likes and dislikes. It’s a tool. These symbols are tools. Repetition is the force that puts these tools to work.

BLVR: Guston had his lightbulbs and eyeball. Dunham has his spread legs. You have croquet mallets.

KM: I’m perpetually building up a lexicon. Playing with icons is like having little proxies for my thoughts. Like placeholders that keep notions cemented in place. It’s also my personal mythology. To give an example, there’s this one particular high heel that I have painted a lot of times. It’s a great shape. It’s iconic. But then I read about how the shoe was hot, how it was selling out of stores at record pace. I didn’t know when I first started using it as an image that I had succumbed to something about it. It began taking on a new meaning for me after that. It was an icon that represented the linking of my individual desires to thousands of others, and now it represents not a shoe but an idea that I am—like it or not—sharing similar thoughts with an unknown amount of people all the time. Whenever I want to talk about this idea in my work now, I use that shoe.

BLVR: What about the leprechauns?

KM: The leprechaun was a self-portrait. Thankfully, I’m over the leprechaun series now, because it came out of a difficult time for me personally. They are probably the most aggressive works I have ever made… especially the paintings of leprechauns jumping out of coffee mugs. I realize in hindsight that I was trying to destroy something inside me, and for some reason it manifested as this symbol of a leprechaun. That was the by-product of my internal dialogue about greed and frivolity. But really, I don’t like to talk about the leprechauns too much.

BLVR: The symbols give a sense of logic to your work, as if you’re building a language that could be decoded. Do you plan a lot of your work with logic?

KM: The goal is a form of strategy, or logic, that will accelerate the work through the actual creation of the artifact. This is not a very romantic approach, I know. I’ve spent a lot of time practicing faux-finishing techniques and thinking about paint-by-numbers so that I can have more time to spend in the conceptualizing stages, where I am most happy. I tend to shy away from expressionistic concerns that compromise control. In a sense, everything in my art becomes about particular processes. That’s how process became the most important part of my painting. I always say that I’m not a particularly good painter but I’m a very strategic painter. So it’s really about the long story behind the surface, not necessarily the surface itself. The painting as an artifact is just the tip of the iceberg.

BLVR: Even though your paintings are very controlledlooking, sometimes there’s a rogue paint smear.

KM: The actual realization of a work is a very controlled thing for me. But sometimes, yeah, I like to add contrasts to remind the viewer of the idea of the artist’s hand at work, and I’ll meticulously paint a fucked-up brushstroke. Sometimes I will use the Xerox machine to obtain a particular “mistake” and transfer that onto the work.

BLVR: When you say “the idea of the artist’s hand,” do you mean the romantic idea of the painter in his studio?

KM: The image of the artist toiling away is so foreign to me. I guess I’ve just lost all love for virtuosity. It doesn’t interest me right now. We’re a generation that grew up with Jeff Koons and co. In the past, if I added an abstract- expressionist gesture in the work, it would have to be cheeky.

BLVR: To keep on this idea of meticulous mistakes, I’ve noticed that a lot of the inconsistencies and mistakes in your work create a sort of illusion. You’ll paint a grid but purposely offset a few of the lines.

KM: With good advertising, as with good art, it can’t just be completely mechanical or you’ll trust the image too much. You won’t take the time to break it apart. But all of sudden, if something catches your eye and it’s askew, you get drawn in, even for a millisecond. I try to consider my drawings and paintings as pure objects that hopefully draw people in—like a typo in a text that you can’t pull your eye away from. Even if someone dislikes my work, I want it to leave a tiny imprint in the background of their mind. Maybe they’ll forget my name. Maybe they’ll forget the piece. But maybe they won’t forget that one fucked-up little shadow that’s going in the wrong direction. Hopefully, it’ll come to them later, in ten years, in a dream, and it’ll wake them up and they won’t know why. That’s what I want. I want art that wakes people up in a decade.

BLVR: And you want to do this through a sort of “flatness” to your image?

KM: I gave up figure-ground relationships a long time ago. I understand perspective, but I’m just not that interested in it. It is a device artists use to make the viewer trust their representations, to show importance through scale. I don’t want the person in the foreground to be innately more important than the person in the background. That is so far from my thinking about relationships in art and in life. I try my best to approach the world I exist in as if there are no hierarchies. I want the paintings to reflect that. These things exist together. Why? How? What’s their spatial relationship? I have no idea.

III. THE FENCE

BLVR: Your blog, Mauve Deep, is filled with all kinds of images. Do you “curate” the blog in any way?

KM: I like that the Internet allows information to pour to me indiscriminately. From high fashion to design to obscure music, sites about art history and theory to blogs about cakes and pastries. It just comes to me now. I’m not looking at visual information with specific intent anymore. I’m taking it in as a steady stream. That’s how information currently feels. It’s certainly very different from seeking things out as we used to have to… going to the image bank or to the library, researching with the Dewey decimal system. Someday the kids will laugh about this, too, and it will also be antiquated in the same way the Dewey system is to us. That’s an exciting notion. It’s funny that people try to fight it, because it feels easier than ever before to learn and grow.

How did I not see the world this way before? I’m an information fiend. Things are changing so quickly and I don’t want to oppose it. It’s too much work to have an opinion of one’s own, and with the steady flow of information coming at us now—maybe we’ll transcend the idea of individual perspectives and move into a more collective consciousness as a whole.

BLVR: It’s tiring to have opinions all the time.

KM: That’s the thing. I don’t know if I was always impartial and this way of thinking about information— especially visual information—lined up with it, or if this flow is influencing the way my brain works.

BLVR: And yet, in so many cases, art is so much about making choices based on opinions. Do you try to get away from that?

KM: I was looking up synonyms for natural the other day and I found artless. I really liked that, to make a work without a gesture or an opinion. I realize, more and more, that I don’t even have an opinion. I’ve been consistently on the fence about everything for the last fifteen years. It’s hard for me to find things I dislike across the board. I wouldn’t say there are many things I like across the board, either—maybe 1 percent on either side. The rest of the stuff I could go either way on. But the thing with me is, I’m not opinionated but I am very particular. I don’t know how I can be both, but I am.

BLVR: A lot of people refer to you as a self-taught artist. Does that term self-taught make sense to you?

KM: Yeah, I would say so. I have devised all of my own techniques from imagination. No one ever showed me the “proper” way to make an artwork. I’m all about invention. I like the approximations and reflections that tend to exist around the fringes. I love looking at faux finishing techniques and I love to watch some Bob Ross wet-on-wet painting from time to time. I learn a lot from that stuff. Sometimes I try to do the opposite of what I imagine a certain artist might do. Sometimes I see a painting and I’ll spend my time not looking at the painting itself or thinking about its subject, but thinking, first, How did the artist make this effect, and, second, Can it be simplified? If I can answer those two questions, I’ll just try it in my studio. That, in a sense, is self-taught.

BLVR: You talk about the fringes, but at the same time you exist pretty squarely within the so-called art world. Your work is shown in a gallery in Chelsea, for instance.

KM: Oh yeah. It’s too hard on the fringe. It’s hell on an artist. But I still appreciate the edges very much. And my work definitely talks about some fringe concerns. I’m not above the fringe. I just want to wrap my fringe concerns in little packages and deliver them to people with perfect bows on top. That’s a perpetual push-and-pull. Move with the energy. Make things easier for yourself while creating platforms for your ideas to be driven further into the masses.

BLVR: You’re not painting as much these days. More drawing and sculpture.

KM: Painting is just so messy. I hate getting paint on my hands.

BLVR: Is that right?

KM: No, no, I’m just kidding.…

BLVR: That could be your answer. It’s a nice and simple reason.

KM: OK, it is true. I wasn’t kidding. I just felt bad about giving such a shallow answer.

BLVR: It’s a surface reason.

KM: Right. I do love the surface. And I love the immediate. Drawing is immediate. I’m going through an immediate phase right now. I don’t want to stick with an idea. I just want to get things down on paper. I’ve been consuming products and bullshit, and now I’m purging….

BLVR: Wait, you think products are bullshit? That seems different than the way you were talking about them earlier.

KM: I’m so flimsy. I’m so fickle. But you can print all this. I’m swayed by whatever’s in front of me. I’m conflicted. I’m such a Gemini. I don’t have any limitations or opinions. I want to make candy. I want to make things without having to make up my mind. I just want to make what I want to make.