Keith Knight is a cartoonist who has been doing running commentary on his own life for over a decade. His weekly strip, The K Chronicles, has been a fixture in alternative weeklies, and online at Salon magazine, since the mid-’90s. Drawn in a loose, noodling style, the strip riffs on a variety of topics: family relationships, life on the road with his “semiconscious” hip-hop band, the Marginal Prophets, observational humor, and politics. (He draws Bush as a boyish little homunculus.)

Taken together, the strips form something of a memoir-on-the-fly, though a deliberately suspect one. While there are real incidents and real characters (Keith’s wife, Kerstin, and his dad make regular appearances), there are also fictional characters (a lunkheaded ex-roommate named Gunther, for one), and events that deliriously skitter far outside the zone of plausibility. He’s less interested in the unvarnished “truth” of life than in the humor of it—he raids his own experience with the giddy zeal of a stand-up comic or an inveterate fibber.

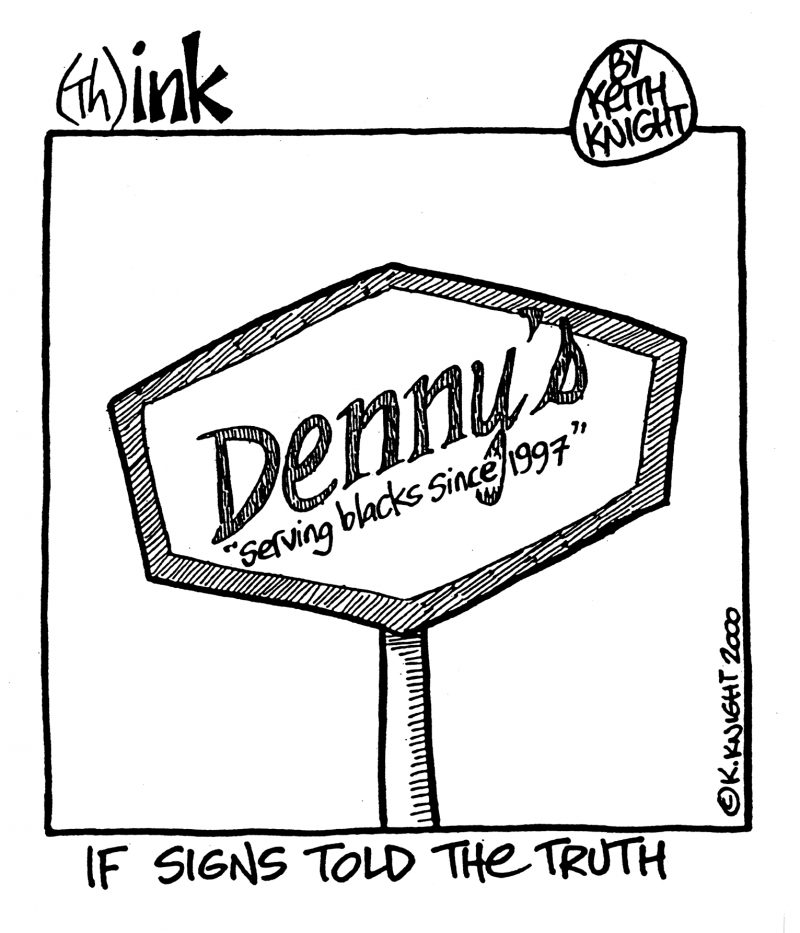

In addition to The K Chronicles, Knight pens a weekly single-panel editorial strip, (th)ink, the SportsKnight strip for ESPN The Magazine, and two strips for MAD magazine, Bully Baby and Father O’Flannity’s Hot Tub Confessions. Most recently, he launched a syndicated daily newspaper strip, The Knight Life, which maintains the The K Chronicles’ balance of autobiography and fabrication while somewhat dialing back the scatology. Part of the kick of The Knight Life is seeing how close to inappropriate Knight is allowed to get, wedged between the Garfields and the Blondies of the world.

This interview was conducted in a café in the Mission District of San Francisco, a city Knight lived in for several years. (He relocated to Los Angeles in 2007.) He was in the city for a slideshow of his work, just ahead of the opening of an exhibit of his cartoons at the Cartoon Art Museum. Since the conversation took place, a number of topics that were in a state of immanence have actually come to pass—most momentously, the birth of his first child, and slightly less momentously, the publication of The Complete K Chronicles, a collection of ten years of his K Chronicles strips. In fact, both book and baby made their appearance on the same day.

Knight quickly commemorated the double event in The K Chronicles, demonstrating his desire to avoid the pitfalls of “cuteness” while keeping true to the autobiography of his new fatherhood. His son’s first appearance in the strip compels his parents to note how deliciously edible he looks, and a bout of parental cannibalism follows. When I mentioned that his son was born into both a family and a comic strip, Keith remarked: “That’s true. His life is going to be recorded for posterity. I’ll just say: ‘Look at this. Look at the way you embarrassed me as a kid. So go do the laundry.’”

—Chris Lanier

I. “BORED KID IN STUDY HALL”

THE BELIEVER: Looking at your sketchbook here—

KEITH KNIGHT: [Pointing to a drawing in the sketchbook] That’s Clive Owen, by the way. Clive Owen at the airport in New York.

BLVR: Do you take this sketchbook with you everywhere?

KK: Yeah. There’s only two blank pages left in that one, although there are lots of little parts on the side that I could fill in.

BLVR: Yeah, it’s very top-to-bottom, really filled in. Just to describe it, it looks like on every page you’ve got about three layers of drawings going on. A bottom layer in black ballpoint pen, and then maybe a layer drawn right on top of that, and another layer on top of that one, in red ink, just drawn over the other drawings. What do you use this sketchbook for? Is it observational? I guess you saw Clive Owen, and broke out the sketchbook….

KK: Broke out the sketchbook, yeah. It depends. Sometimes I use it to work out dialogue, sometimes I use it to record something. Maybe there’s a look I’d like to get down. Or it’s working out gags, working out drawings, working on eyes. Eyes are probably what I spend most of the time working on. Trying to get the eyes right.

BLVR: You work in a pretty simplified style, so what would be some of the nuances of getting something “right” in the eyes for one of your characters?

KK: I don’t know exactly what the system is, but I bet if someone analyzed it, they’d figure out what my system is for making certain eyes. There are dots, or sometimes there are lines for the pupils, within the circle. But there are never lines for pupils when there aren’t circles around the eyes. It’s just more dots. And… [gives up.] Yeah, I don’t know. [Laughs]

BLVR: So you don’t have a system for it at all.

KK: No, no. I know which characters have big circle eyes—my character does, Kerstin does. But then there are characters that just have dots for eyes. And then when I draw myself real small I’ll put dots for eyes. The eyes are a big Chuck Jones influence, because he was all about the eyes. When you look at his work, it’s all about the look and the eyes.

[Pointing out a picture] Like this drawing. This woman’s sort of psycho. And the separation of her eyes a little bit, and the fact that the line, the pupil, is right in the middle of each one—it makes her look psycho. If you move her eyes a little bit, it expresses a whole different thing. You can do a lot with the eyes.

BLVR: And then this layering. The three layers of drawings going on here, superimposed—what is that about? Is it a space-saving thing? Was this sketchbook so expensive, you’re trying to squeeze every drop out of it?

KK: Actually, it was a nice gift. It’s a really nice book. But it’s just that, if I get an idea, I don’t want to do it across several pages. I want to keep it on one page. Bang! That’s the idea.

BLVR: I’m with you that far, doing one idea on one page, but then it looks like you go over that idea with another pen, and you draw other ideas right on top of that.

KK: I guess I see it in layers, especially with the different colors of ink. It’s real easy when it’s a different color. Even when it’s not a different color, I can tell what I was working on, and refer back to it pretty easily. I don’t understand why I do it. [Laughs] I don’t understand. Maybe it is because I don’t want to spend money on more books. The frugality. I am the Friar of Frugality.

BLVR: You know, these pages kind of remind me of study hall. A bored kid in study hall.

KK: That’s exactly what it stems from. This is exactly what I did in grade school, and high school. I just continued to do it. Now I get paid a little bit for it.

BLVR: And how much of this is observation, and how much is it thinking through gags?

KK: All this is based on truth somehow. And then the cartoons spin out from it. If I drew everything according to real life, it would be rather boring. When you take it and put it in a cartoon, you have to make everything extreme. I’m working on a story line about my brother-in-law, who’s in town, visiting from Germany. And the euro is really strong. He’s going around buying stuff. But if I wrote about him buying an iPod, there’s nothing funny about that. In the strip, he’s hiring Kanye West to play my backyard, and buying the naming rights to the L.A. Coliseum. Stuff like that. You just make it extreme.

II. DECENCY AND OTHER CHALLENGES

BLVR: A shift in The Knight Life, after having done The K Chronicles in the alt-weeklies, is the change in decency standards. You push the edge in your weekly strip, but I’m wondering how you’re approaching this daily strip, knowing the kind of humor you can pursue is going to be more constricted.

KK: I see it more as a challenge. Art is defined by not only what you have access to but what your limitations are. The Knight Life is a different strip, because I have to work within those parameters. It’ll rise and fall on its own merits. I like the fact that I can’t just go to an ass joke. I will do my best—

BLVR: But that seems like such a strong part of your arsenal.

KK: I will do my best to get one in there, but believe me, some of the upcoming ones—there’s some nudity, and things like that.

BLVR: Nudity? How do you approach nudity in a daily strip?

KK: Well, obviously it helps that there isn’t a lot of room. So stuff gets cut off in time, by the panels, before it gets down there.

BLVR: How clear are the decency goalposts to you? Do you, as a syndicated cartoonist, get some piece of paperwork that says, “These are the rules”?

KK: No, they don’t write it out. The one thing I don’t do is hold myself back. I don’t say, “Oh, they’re not going to go for this.” I just do it, and then Ted Rall, my editor, writes back: “No, no penis jokes, no fart jokes. Change drugs to stash.”That’s actually one of the things. Actually, crap just ran in the paper. And somebody wrote to me, “Wow, I don’t believe they let you put crap in there.” So there you go.

BLVR: Are you looking toward any other cartoonists, as far as figuring out how the rhythm of a daily strip goes?

KK: I look at other cartoonists for what not to do as much as what to do. There are certain things I make an effort not to do in The Knight Life.

BLVR: Such as?

KK: I don’t want to date my strip. One thing that The K Chronicles is known for is that it’s indirectly political. It’s political, but on a personal level. I’m trying not to name specific incidents in the daily, things that automatically date the strip. When you look at a timeless strip, like Peanuts or Calvin and Hobbes, they don’t make any reference to who’s president at the time. But you look at the old Bloom Countys, and they’re automatically dated. I want to see if I can walk that fine line of dealing with contemporary issues without instantly dating myself.

BLVR: On the other hand, it does seem like a lot of your material deals with a lot of pop-culture references. Is that a conundrum for you?

KK: Yes and no. It’ll be in there and it won’t be in there. For me, I’d rather say, “The president is a moron,” and everybody knows who I’m talking about. As opposed to saying, “Bush is a moron.” Because it doesn’t have to be that specific. And we’ll always have a president, and chances are, they’ll generally be regarded as a moron by somebody, in some way, shape, or form. Obviously, if it’s relevant to the humor, then I will get specific.

BLVR: But isn’t part of the function of a daily strip to be ephemeral?

KK: [Laughs] I don’t think so. I think it’s something someone wants to turn to every day, but I don’t think it’s something that specifically has to talk about what’s going on, on that day. Like doing an Easter strip on Easter. I would love to do strips on specific, obscure holidays, as opposed to the big ones. Arbor Day and things like that. I like doing the real obscure references that one or two people will get. Those one or two people freak out, and you’ve got a fan for life.

In one of the early Knight Lifes, I talk about being a sports fan, and I’m cheering and waving a flag that has the Washington Generals on it. The Washington Generals are the team that loses to the Harlem Globetrotters every time. This one guy wrote to me, and he was so excited about it. I said, “I want to make it cool to wear Washington Generals gear all the time.” And he says, “Yeah, I’d love to have a ‘Klotz’ shirt.” Klotz is the name of the guy who started the team, years and years ago. For that guy to know that… is pretty scary. One that ran last week, I talked about scratching. It says scratching the turntable was invented by this cat in Brooklyn. And in the strip, it’s a real cat scratching the record. But the cat’s name is Theodore. And this one friend of mine, a huge hip-hop fan, knows that Theodore is the name of the guy who really invented scratching, Grand Wizard Theodore, in the ’70s. Those types of things—if someone gets it, that’s great. If people don’t, they may find some humor in it. But the super-cool humor [laughs] is under the layer. Which brings me back to the layers in the notebook.

BLVR: It’s all making sense to me now.

KK: It’s all a big theme.

III. “ THAT ONE BLACK KID”

BLVR: Is that part of your job, in a daily strip? To be a cultural smuggler?

KK: A cultural smuggler. I like that. I think so, in some ways. Basically, what I want to do as a cartoonist is to make a strip that I like. I just try to make something I like, because I know that there are a lot of people out there who have something in common with me. That’s what I’m doing more than anything else. I guess it goes back to the whole idea of representation in media. I’m making a comic with black characters that don’t fit the stereotypical role. Yeah, I like rap, but I also like other stuff. I’m a huge Clash fan. I believe the Stanley Cup playoffs are the most exciting sports to watch. I don’t think it’s my duty, but making those references—it makes me think of the “One Black Kid” strip I did. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen that. “This is dedicated to that one black kid.” I go through the strip naming black kids that didn’t fit in. The black kid who’s into heavy metal. The black kid who’s living out in that town, when you’re driving down the 5, and there’s this dirt road that goes off to this little town, and there’s one black kid there. I go through it, naming off all this stuff, and then, in the end it says, “This is dedicated to that one black kid,” and the picture is all these black people holding their hands up and saying, “That’s me.” And that really resonated a whole lot. I don’t think I’ve ever gotten more mail.

BLVR: In putting work out there that’s going against some of the myths, or some of the stereotypes—do you feel like things are genuinely shifting? There’s so much coming out around the Obama campaign—

KK: Yeah.

BLVR: He’s having to negotiate this minefield: is he black enough, is he too black? And it seems he’s really trying to make a nuanced way through it. Half of me feels, Wow, this is really great, he is really messing with the dominant ideas of what constitutes race. And then on the other side of it, after he makes this great speech on race, you get all these reactions from pundits that are just idiotic, fixating on the idea that he dissed his white grandmother in the speech. Do you really feel there’s been some actual positive drift in the culture? That you’re a part of?

KK: Ah… it’s tough to say. It’s weird. If he gets elected, people will use that as an excuse—“See, we have a black president, we don’t have racism anymore.” It doesn’t change the dynamic of that whole system that allows cops to blow away black people and just get off. Just walk away. That doesn’t change. What he is going through is insane, because it’s damned if you do, damned if you don’t. It’s extremely complex. I think it’s cool, because people are talking about things, and people are showing parts of themselves that, in the past, they wouldn’t say anything about. But now you see that there are people who will not vote for a black person. Or who say they will, and then they go in and they won’t do it. That just goes to show you how much further this country needs to go.

BLVR: Is it part of your inspiration, or part of your drive, to be negotiating that kind of political terrain—to essentially, in your way, in your corner of the universe, redefine blackness?

KK: Certainly not. But to show that there are, for lack of a better word, different shades of blackness. There are so many different aspects of black culture. How I grew up, and the music I listen to, and the work I do—that’s one aspect of it. There are all different levels. I think about the guys I grew up with, and how they’re coming up, and it’s way different from what you see—the typical depictions of a black male in newspapers, in the news. I remember my cousin walking down the street. He had pictures of his kid and he was showing them off. And this one girl said to him, “Wow, that’s really cool that you stuck around.” [Laughs]

BLVR: What a compliment.

KK: Yeah. It was really weird.

BLVR: Does it function, in a funny way, as one of these boundaries to push up against? There’s the boundary of what’s acceptable, humor-wise, and then there’s the boundary of what’s acceptable as a human being, politically?

KK: I guess it’s a boundary for other people to cross over, in their thought process. I get a lot of emails from the fifty-three-year-old white males, who say, “I’m a fiftythree-year-old white male, and I like your comic strip.” As if it’s a shock: “I don’t believe it.” And I always say, over and over again: half the stuff I like, Star Wars movies, whatever, are done by fifty-three-year-old white males. So if I like that, what makes it so hard for you to say you like my stuff? Why is it such a shock? And they just get bent out of shape.

BLVR: They don’t receive that reply very well?

KK: No, no.

BLVR: That rolls into that comic-strip action, or comicstrip protest, that you were involved with, with Corey Thomas and Darrin Bell. Could you explain a little bit about what that was, and how you got recruited for it?

KK: That was an action by a group of black cartoonists. More than that: Lalo Alcaraz joined in, and a few white cartoonists joined in, too. Corey wrote a strip, and everybody else drew their characters doing that strip. Everyone did it in their own style, but it was the same gag. The gag was this white guy getting mad because there’s more than one black comic strip in the paper. “Another Boondocks ripoff! Why can’t they put in cartoons that everybody can relate to?” And then someone else says, “ ‘Everybody,’ meaning you?” And the last panel has the white guy laughing over Dagwood, or Beetle Bailey. “Oh, that Dagwood!” Everyone picked a different comic at the end to make fun of. I picked Andy Capp, and had the guy laughing, going, “You gotta love Andy Capp and his chronic alcoholism!” I originally put in two gags, about spousal abuse and alcoholism, but just went with the chronic alcoholism.

BLVR: I thought your strip was the funniest because it was not only the joke about representation, it was also a funny jab at Andy Capp.

KK: There you go. Always going one step farther. The whole thing made a great point, and it got so much publicity, because papers sit there and go, “Oh, we have a black strip, so we can’t put another black strip in there.” Come on, give me a break. If a strip is funny, then put it in. The comics page shouldn’t be like a jury. There can be more than one black person on the comics page.

IV. SUNDAY MORNINGS

BLVR: You’ve alluded to the fact that daily strips were what got you interested in cartooning. What were some of the strips that you were looking at as a kid that really hooked you?

KK: Well, I was reading Mutt and Jeff. That was at the top of the page in the Boston Globe. I was fascinated by Andy Capp—not only the chronic alcoholism and the spousal abuse, but also the dialect. My dad would tell me, “That’s how they make it sound like there’s an accent.” Now when I do dialogue, I really try to make it sound like the way I would talk. I remember my uncle showing me The Lockhorns, and how their heads float above their bodies—they’re not connected. So you’ll see in my drawings that I don’t connect a lot of things. Which is a nightmare for anyone coloring it, but too bad. My favorite strips, coming up, were Peanuts and Doonesbury.

Doonesbury was the first strip that had black people in it, acting like black people, taking on black issues. It was a big influence. I remember going to the library, and the two cartoon books that they had were Peanuts and Doonesbury, so I would read a lot of Doonesbury. I liked the idea of real stuff, real issues, mixing with these fake characters, and with real characters. I think that was the first idea I had of meshing fiction and nonfiction.

I also liked leaving the comics page and looking for other comics in the paper, in the classifieds or in the editorial page. Feiffer was in Parade, and he was the first one I saw that didn’t have panels a lot of times. That was really cool. And then Parliament/Funkadelic albums, just buying those and sitting there and looking at them, and MAD magazine, with the Sergio Aragones cartoons along the edges. It was a combination of all that.

BLVR: It seems there are a lot of vivid sense memories for people around reading the Sunday comics.What sorts of things does it evoke for you?

KK: Just coming down in the morning, grabbing it, reading that and Parade with Feiffer in it, having breakfast and waiting till the football games start. It reminds me of Massachusetts, mainly, ’cause I grew up there. Leaves falling, and snow, all that stuff, I associate that with sitting around with the paper. I guess it reminds me of family, too. We all read the paper. The other thing was, we were a Globe family, the Boston Globe. And my uncle up the street, he was a Herald guy. It was great to go up and visit him and read all these other comics, which were in the enemy paper. I remember, I forget the name—like The Moose, or Moose MacGillicutty, “Moose” something—it was this dirty-ass family that just had cats everywhere, and everything was trashed all the time. Bones lying around the living room. It was a big mess. And I loved how filthy these people were. It was “Moose” something; it might have been The Mooses.

BLVR: So there was something contraband about that one.

KK: Yeah, and also the Herald had the two pictures, “Find the six differences in these two pictures.” That made it worth it going to visit my uncle. But now The Knight Life is starting up in the Herald, it’s not running in the Globe. Those bastards at the Globe.

V. KEEPING A PUBLIC DIARY

BLVR: Now you’ve got this big compendium coming out, collecting most of your K Chronicles strips. How does it feel, after a dozen years of working, to suddenly look over your shoulder and have this massive thing behind you?

KK: It’s cool. I really didn’t think about how cool it was, until realizing that we’re gonna have a son, and it’s just that—I mean, I’m not going to show it to him anytime soon.…

BLVR: You could probably be thrown in jail for that.

KK: Yeah. But you know, at some point I can just sit there and say—“You wanna learn somethin’? Just read this.” It would be great to get a comic book to read, and by the time you finish it, you can see: “This is why my dad beats me.”

BLVR: With the collection—looking back, is there anything that surprises you? Things that make you say, “Oh yeah, that’s what that was like.” If you hadn’t been doing a strip, you would’ve totally forgotten about it.

KK: Not really, ’cause I remember practically all the strips. What surprises me is when people comment and say, “Oh, I really like this strip. This is my favorite strip.” The one that got me the most mail, besides the “One Black Kid,” was one I did about bacon. It got me the biggest mail, and started the biggest controversy—from vegans. People were sending me bacon recipes, and this one dude wrote me and said he makes bacon milkshakes. Bacon and maple syrup milkshakes. He used to do it when he worked at this diner, in Portland. And then when my wife and I went up to the Stumptown comics festival out there, he was there. He came up and he said, “Hey, I don’t work at the diner anymore, but I’m sure if we went by there tomorrow morning, they’d let me go back there and make a bacon milkshake.” I was like, “Listen, man, I don’t want to go there.” He says, “No, seriously…” He said he made it once for Matt Dillon, or maybe it was Christian Slater, and he goes: “He really liked it!” It was some weird thing. I said, “No, man.” He wanted me to get up at seven o’clock in the morning and meet him there for the bacon milkshake. And I said, “I do wacky things, but that’s a little too wacky for me.”

BLVR: Is there anything that didn’t make it in there that surprises you? Parts of your life, parts of your personality that never made it into the strip? Parts of yourself that were kept out of it?

KK: Oh, there are plenty of parts. I have to make myself look good. [Laughs] As much as everybody wants to see the worst parts of people’s personalities, if you’re doing the editing, you’re not going to allow that. And there are a lot of things about family and friends that I wouldn’t write about. When people say, “I feel like I know you,” it’s always—“Eh, you don’t really know me.”

BLVR: I’m curious if mining your own experience for the strips gives you a certain split-level consciousness about what you’re going through.

KK: It does, a little bit. I really felt that way when I witnessed someone trying to kill themselves jumping in front of a BART train. That strip was in Passion of the Keef. I was standing there, thinking, Wow, am I really going to watch this person get hit by a train? Am I really going to stand there and watch it? She was on another platform, it was way too late to go over, run all the way down the platform, over the stairs, go across the other side and try to grab her. There were already enough people running up the platform to signal the train to stop. There was nothing for me to do, but honestly, I was trying to just look at her, and kind of… just look at her and convey, “Don’t do this.” To connect. And the way she looked—I’ve never seen anyone who had so given up on life. But the idea that “Yes, I am going to watch this”— that was kind of strange. I could do a much longer story on that one strip.

BLVR: While you’re watching it, there’s a part of your brain going, I’ll probably use this in a strip.

KK: Probably in the back of my head. Definitely.

BLVR: There are also some strips that cut even closer to the bone. When Kerstin had a tumor, that was material you used for the strip. It’s in the collection I Left My Arse in San Francisco, right? I’m trying to remember, did you start doing the strips before you knew the outcome?

KK: No, no. It was definitely one of those things where I did not start it until I knew what was going on, because it would’ve been hard to grasp how to move forward if it was a negative outcome. Many people were writing in when those strips ran, saying, “I hope everything goes well.” It’s tough not to say, “Oh, everything’s fine.” You wanna leave them hangin’ for two weeks. So that was kind of weird.

BLVR: [Laughs] So you were stringing the audience along….

KK: Yeah, yeah. It was weird. But also it was amazing, the outpouring of people. They wrote in and offered not only their sympathies but their services. Doctors, and the DanaFarber Institute, and WebMD wrote to me. Somebody with a bed and breakfast in Vermont invited us there. Just amazing, the outpouring. And amazing, the people who contacted me, who went through the same thing. Brian Fies, who won an Eisner for his Mom’s Cancer book, wrote to me. One heartbreaking thing was a guy who came up to me at WonderCon and said his wife had cancer. They were twenty-six or twenty-four, something crazy like that. And we saw him, and he said, “Thanks for doing that.” The next time we saw him, she’d died. And what can you say? To be able to make somebody for a second feel a little better, or to feel like somebody can kind of relate to what’s going on… you can’t ask for much more than that. Besides health insurance.