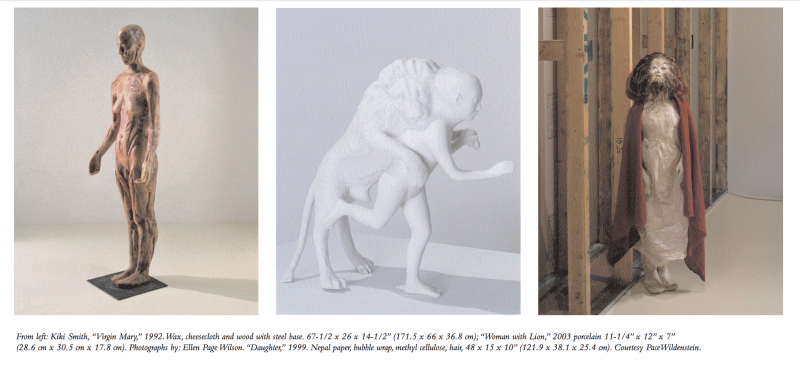

Kiki Smith is generative and genuine, and, like a King Midas, everything she touches turns into art. Sculptor, painter, printmaker, videomaker, photographer, she has been an artist all her life. Smith is constantly building and doing: house-painting, carpentry or electrical work, rendering quick sketches, knitting, making art. Her work varies in medium, size, and material. Smith’s portrayals of the human form, for which she is perhaps most famous, range in scale from life-size, hanging bodies to figurines.

Smith was born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1954, then moved to a New Jersey suburb in early childhood. Growing up, Smith and her twin sisters, Bebe and Seton, were surrounded by artists. Her father, Tony Smith, was a renowned minimalist sculptor; her mother, Jane, was an opera singer and a close friend of Tennessee Williams. In a way, Tony Smith’s art was a family affair. Smith’s childhood was dominated by her father’s Abstract Expressionist crowd, with dinner-table talk about art and aesthetics. Their suburban lawn had a Tony Smith sculpture. So, unlike many kids who rebel against their middle-class upbringings, Smith had to adjust to an artist’s life. For her, it’s normal. Her journey from seeing and hearing about art to making her own was mostly a continuous one.

Early in her career, Kiki Smith joined the artists’ collective Collaborative Projects and contributed to the famed Times Square Show of 1980. She had her first solo show at the Kitchen in New York City in 1982. Her second, in 1988 at the Joe Fawbush Gallery on Broadway, was provocative and revelatory. She exhibited huge pharmacists’ bottles of bodily fluids—sperm, blood, urine, and human fetuses among them—which sat on a shelf on one side of the gallery. With this show, Smith burst onto the scene, fully formed imaginatively, like one of her strange, near-mythological figures. Since then, her influence on the art world—particularly on the treatment of women and the body—has been dramatic. Recently, the Museum of Modern Art exhibited “Prints, Books & Things,” a retrospective of twenty years of Smith’s wildly unusual and unique printmaking.

Kiki Smith’s surprising investigations and inventions are reflections of her: she’s intense and casual, friendly and private, shy and forthright. She discusses Catholicism as readily as she does sex and bodily functions. And, for one of the most influential artists of her day, she’s refreshingly modest and candid. As we talked on the second floor of her house in the East Village, Smith worked on a small clay sculpture. Her pet bird, Birdie Bird, flew in and out of the room.

—Lynne Tillman

I. NUNS AND OTHER METAPHORS

THE BELIEVER: There’s a quality of isolation to your figures, which are often singular objects, set apart and shown in large spaces. Do you see them as alienated?

KIKI SMITH: I always see my sculptures as a little bit like statues. I don’t know exactly what statues are, but they’re not illustrations of life, but like separate entities in space; it’s what statues exist in. One of my favorite stories is Abraham playing with his father’s idols—his father was an idol-maker. Abraham breaks one and the father comes home, and he’s angry that it’s broken. Then Abraham says that one of the statues did it to the other. His father says that they’re just statues, and Abraham talks about believing in one god. But I always liked the staticness of the statue, maybe something like playing freeze tag, or playing statues when you were a kid. Or statues in churches. I think my work is in a different realm. It’s not a naturalistic realm. It is in another realm.

BLVR: I think of your work, even though it often uses bodies, as antinatural.

KS: It does have a kind of stiffness. But I think that probably about myself, too, though I think of myself as not being isolated.

BLVR: Your studio is a whirl of people coming and going. You’re often surrounded.

KS: But I do always have a fantasy of being a nun, in a silent convent.

BLVR: So maybe each of your statues is a nun. [Laughs]

KS: They’re playing out my nun life. I thought recently, only two sculptures I ever made, large sculptures, were a male and a female. And they didn’t touch one another. They were very separate from one another. One was: they’re both suspended, their milk and semen are falling down. The second was a female sucking her breast and a male sucking his penis, so that they were self-perpetuating. It’s called “Mother Child.”

BLVR: Not “Man and Woman.”

KS: The mother was mothering herself and the child, and the man was like the child. It was about being self-contained in their own systems. I don’t want them naturalistic. I think that’s the biggest problem of making figurative sculpture or making art in general. Where I’m critical of my work is when I see it being illustrational. I don’t want to make illustrations, particularly. Probably sometimes I do that, but not on purpose. But when it fails, it’s an illustration of something rather than an experience.

BLVR: Looking at your figurative work, I see the body as a source of metaphors. I think that’s the way you use bodies.

KS: Absolutely. I never mean any of it literally, always metaphorically. When people speak to me in a manner that says they read it literally, I’m sort of horrified. I act like,“What are you, crazy?” But it is a physicality. Now in the last couple years I’ve made women with animals, because I believe that sculpture can be active; but there’s a way that I also like the statue as a stiff. There is a kind of…

BLVR: Deadness to it.

KS: Deadness and frozenness. Once I saw an episode of The Outer Limits or The Twilight Zone, probably when I was making all these figures, in which a man becomes a famous artist. He dips his girlfriend by accident into a vat, or murders her, or a cat falls into a vat of plaster, and then he starts dipping women into vats. He becomes very famous as a figurative sculptor. His figures are in strange positions. But he accidentally became a murderer, then he happened upon a good art career. I sort of feel that a little bit.

BLVR: You give clues to your work’s fantasticness. That sculpture of a head with chains coming out of it. It makes associations: thoughts are like cages or…

KS: That’s how I mean that. The body as a trap or the body as a drain, there’s a lot of drainage.

BLVR: Also, when you do pieces like beads trailing out of a vagina or hundreds of glass sperm on the floor— they refer to bodies, what drops out of bodies, but they seem abstract to me.

KS: Also for me. I would say 90 percent of what one’s doing, or anyway, for me, in a way, is going over historical terrain. Playing in it, historical forms, playing in them. So you might make the beads a body’s fluids, but it’s probably really interesting to see it as sculpture that incorporated decorative art’s history and fine art’s history.

BLVR: By using beads.

KS: Yes. To me often the main interest is really, in a way, to have all: you have to have a form, then you have formal issues you’re playing with, and then you need an emotional, vested interest in the object. But the content is also simply coming out of my interest in the history of decorative art. That’s the part I talk about the least, though, because it’s easier to say that this is some emotional, chaotic…

BLVR: But you’re working within forms and…

KS: An idea in my brain. I want to make something, I want to do a scale of figurines and what figurines mean, like table figurines, or to make small porcelains because I’ve never done it before. So it’s a matter of trying to figure out how you could make your own version of the world. It’s like making your own version of the world but using historical forms that exist already. I’m not somebody making up any new forms at all. I like what exists already. There’s so much that exists already that’s so fascinating.

BLVR: When you made those hanging paper bodies— you would hang just one or many—there was something new about that. It’s not that paper is new, and it’s not that representing the body is.

KS: No, it’s mixing it up. But it’s like saying that people recontextualize, or it’s rehashing or juxtaposing things they know and using them in ways that weren’t apparent, at least to you before. To me lots of times I know what’s an interesting form, then I don’t know how to use it. Those pieces came directly from Japanese paper balloons that we had as kids.

BLVR: Paper balloons?

KS: Little Japanese paper balloons you get that you blow up. They’re made like orange sections, like a globe, an inflatable globe. My mother used to give them to us for Christmas presents, and so that was just wandering around in the back of my mind. I liked those, and I wanted to make the body as an envelope. This form is this thing. It was something I read from Aquinas, about separating form from matter. I thought I could separate the form of the body from its insides, then I thought, “How would you do that?” And then I remembered the Japanese paper balloons. That’s how you do it.

II. FAMILY RESEMBLANCES

BLVR: I like the idea of the body as an envelope. I think of the novel as a container. And you do matter as content. Like those jars of fetuses.

KS: They were done all at the same time, all because I read some Aquinas. My father had the great books; I read them. Aquinas was talking about angels. But it was all about the separation of form and matter, what ceases to be actual when the form is separated from the matter. I really liked that, and all my work from that time was about that. You know, it was right when my father died, pretty much.

BLVR: What year was that?

KS: He died in 1980.

BLVR: Your father was such an important sculptor. Was it hard for you to begin making sculpture?

KS: I think it was. I always thought that I was lucky that he died, which doesn’t sound nice, but I don’t think I would have become me if my father had lived. Not in the same way. I just don’t think I would have had the courage.

BLVR: He was so big to you.

KS: So, I was somehow in relationship with that, and I felt that, one, I would fail in that relationship, but also as if it would be a betrayal of my family, or a betrayal to be in the same arena. And presumptuous. When he died, I thought none of that mattered particularly anymore.

BLVR: How did you feel about the recent “three Smiths” show in Florida—with your sister Seton Smith, you, and your father having your work shown together?

KS: I thought it was fun. It’s weird, because I felt as if you get to see you have this family, and I don’t know that much about my father and I don’t know that much about Seton in a way, or myself particularly. I realize that, to me, their work is totally familiar and internally, intuitively known. I recognize their work as kin. We’re all individual people just doing their trips and there is appreciation…

BLVR: There’s a family resemblance? [Laughs]

KS: There’s a family resemblance, but the resemblance can be hard to discern, though I can see things. Some people say,“I didn’t ever think about it,” and then my friends say that I use paper as a sculptural material because my father made models out of paper. And it’s true. I spent my whole childhood making paper models for him.

BLVR: I didn’t know that.

KS: That’s all we did all day long: work for my father. So I thought, it makes sense. It also makes sense that I use lots of things, when it’s just all these elements of things. He would make octahedrons and tetrahedrons and put them together, so then it would make one smooth surface. Lots of my sculptures are all the elements separated. I related much more to the Frankenstein model, in which you saw the ruptured whole. There was a whole, but taped together and precarious.

III. MATERIAL FREEDOM

BLVR: One of the first pieces I remember of yours was “Severed Limbs.”

KS: That was the first body thing I ever did.

BLVR: I remember it was a hand, an arm, or a leg…

KS: It was in the seventies.

BLVR: Late seventies.

KS: Because I was making still lifes before that.

BLVR: Something that’s often struck me about your work is your relationship to materials. You approach them with freedom, almost casually, whether it’s glass, clay, paint, bronze or porcelain, photograpy, video. Many artists, I think, keep to fewer elements.

KS: Probably some learn how to do things more indepth than I do. [Laughs]

BLVR:[Laughing] You think you’re superficial about this?

KS: I think I’m superficial. I’m just greedy and hungry and curious, basically. It’s curiosity and then it’s also that you read materials the way you read people or anything else. They have histories you’re conscious of, they have physical properties that you’re maybe not conscious of, but they have histories as materials,times when they were invented. They have historical use, they’re part of technology or not, or they come and go in their technological attraction.They also have ways that you read them…

BLVR:They have certain qualities.

KS: Physical qualities, they have physical ways and they interact with your body, and that’s physiological, it has nothing to do with your consciousness whatsoever, none of the things you’re conscious about, and they carry emotions, they’re economical—many different things are operating.To me, if you’re going to make sculpture, part of it is curiosity, and part of it is just saying, “I want to work in a form,” either a form that exists historically or that has certain material aspects attached to it.

BLVR: Do you ever think about a form, for example, that glass would be more like a poem or a sonnet? I might say I’m going to write a short story or a novel.

KS: It’s the same thing.You’re picking space to play in. Even the same way you would say I’m going to make figurative sculpture or landscape sculpture—they’re just forms that you play with, that you’re making a decision about.The materials also have different qualities so you can utilize that or exploit those qualities. It’s also that you work with one material, then you get sick of it and want to have another experience.There’s so much possibility. Like living in New York. And so to me it’s the same thing in artwork.You have all of history to be a model for making things.You have the entire history of people making things. I actually make things within a very narrow range. I use mostly lumpen materials that don’t have form and that can take form…

BLVR: Like you blow glass…

KS: [Laughs] But you know, I actually don’t blow glass, but somebody does…

BLVR: [Laughs] You use blown glass.

KS: I use artisans also, which is a way that certain people work, too. Other people want to do everything themselves but I don’t have that much attachment to doing every aspect of everything myself.

BLVR:You grew up in a studio situation. You grew up in your father’s factory, in a sense.

KS: My father was famous for ordering his artwork on the telephone, which then became a model later in representational work rather than abstraction. To have everything manufactured. I’m somebody in-between. I derive immense satisfaction from making things. For me what’s interesting is that I don’t have any really great inherent ability to make things. Growing up, I couldn’t make very good drawings, representations. I take tremendous pleasure in the struggle to try and make things look like something.

IV. BEING ALIVE IS MESSY

BLVR: Ever since I’ve known you, whenever I’ve been visiting you anywhere, your hands are busy. Right now you’re working on a sculpture of a man.

KS: No, it’s a girl and a bear.

BLVR: A girl and a bear.The bear is holding her from the rear. It’s very perverse. Your work gets more and more perverse.

KS: [Laughing] I’m just getting more mannerist.

BLVR: When you mentioned glass and materials, I thought about Robert Smithson’s “Map of Glass” piece at DIA:Beacon, how scary that mound of large shards of glass is spilling over the floor.

KS: Commercial, not studio blown glass.

BLVR: Looking at the broken glass, I feared I might just slip and fall on top of it, cutting myself to pieces.You said once that the body was “frail and mighty.”Your use of paper bodies—you could just blow one away; then there’s a head that’s bronze, and chains coming out. Tough and fragile.

KS: I always say the joke is that historically what appears to have strength has weakness and what appears to be weak historically has strength.

BLVR: How do you mean?

KS: Americans have an enormous cultural bias against bronze or cast metals. I was making something, and a curator said to me that now I was working for posterity because I was using bronze, and I thought, that’s historically inaccurate, because it is bronze that could be reutilized. I would say that we are the first generation in which bronze isn’t primarily a material used for weapons manufacturing, and that most of the bronzes of the world have been melted down in times of war. In the first World War, it was a patriotic duty to give your parlor sculptures…

BLVR:To the war effort.

KS: These materials people associate with power just because they have been used to make representations of power are not materials that will last forever.Absolutely they don’t. It gets recycled. But ceramics—we know the history of the world through ceramics or through glass shards and ceramics, because they couldn’t easily be recycled. I mean now, to some extent, glass is; usually it was just discarded.

BLVR: Paintings could be recycled—paint over the canvas and use it again.

KS: But people don’t, generally.There’s not a shortage of material. So it’s a joke to me. I used to play with paper, a very inexpensive material, except that the paper I used to make the paper sculptures cost me about twenty dollars a sheet. It cost hundreds and hundreds of dollars to make something that looks like a piece of nothing.

BLVR: Returning to the 1980s, your father’s death had a great impact on you. And everyone was forced into the AIDS epidemic. Your work has a lot to do with death. I know you’ll say it’s in part about your being Catholic… [Laughs]

KS: [Laughs] Irish Catholic.

BLVR: But there’s another way to think about it. Often when artists use the female figure, it’s to affirm life.Your work contradicts or twists that and links women with death. And when birth is involved, it can be a very treacherous.

KS: I always thought birth was treacherous.

BLVR: You did a piece—a uterus like a cage, for instance.You’ve helped change the way human beings, women in particular, are represented in, as art.

KS: If you look at representation—not in all art, but in Western, figurative art—there’s a small sector of life represented. I used to say that it was women lounging around eating cherries. I’d always joke I was so upset that wasn’t my real life. [Laughs]

BLVR: [Laughing] It’s not?

KS: [Laughing] No, I would much prefer to be lounging around naked all day. But most of my life was taken up trying to get the dishwasher to work or trying to keep one’s insides inside.There was such an incredible open field, this enormous open field in terms of children, also, hardly any representation of children and very little representation of women from the experiential side.There are ideas about the gaze, women being looked at, but not from the active standpoint of being an embodied participant.

BLVR: Your figures aren’t life-affirming. What you affirm, if anything, is that everything struggles and dies, things live and die, bodies are fragile and strong.Your work shows the messiness of being in a body, how messy being alive is.

KS: It’s just terrible. And the older you become, there are all these new messes that nobody ever told you about. [Laughing] People always think I’m serious. Not like now—I don’t think people think I’m serious at all, but when I was younger, people would meet me and say, “I really expected something different.” To me, so much is about making an amusement, like a folly, a folly version of life. It’s amusing citations, about our precarious predicaments in being here.

BLVR: Some people find your work horrifying.

KS: I mean, people go to horror films. I can’t watch horror films. I hate them. I can’t watch slasher movies. I can’t watch the Chainsaw Massacre, because it’s too real. It is too real. I first started making body stuff, those severed limbs, and right afterward we were in the war with Nicaragua. I thought, “That’s people’s real lives.” You shouldn’t use other people’s suffering for your metaphor. This physical suffering had a reality in people’s lives. I stopped using violent, ruptured imagery because I realized it was profoundly real. I felt I shouldn’t use it in a vicarious manner.

BLVR:You’ve said that your work is very close to your own experience.Was that when you decided you should keep it close to your experience?

KS: I might feel emotionally, psychically hacked to bits, but I’m not physically hacked to bits; people were physically being hacked to bits.Also, my life changed.That was close to 1980. I don’t believe that you keep your life for your artwork, to have a certain image.You take care of it, you go where it wants to go and float around. My artwork has often been a protection for me, a way of making an external model,or making sense of my life.But my life has changed a lot, changed for the better, and I come up less with images of dismemberment. I still believe that unconsciously I often think about dismemberment.The animal sculptures sort of came from that again.

BLVR: From dismemberment. How is that?

KS: I made them as prints first. I wanted to make a print of a Rousseau painting from MOMA, because I was going to have a show at the Modern. But then it turned into animals attacking women. It was both playful and sexual; then I thought that really they’re about spiritually, about trying to get out of a body. I want to get out, away from being in a body.Then I started making all these pieces with animals. But then it all just looks like bestiality. [Laughs]

BLVR: [Laughing] Interspecies love?

KS: [Laughing] Yeah.Also, for the past five years I’ve been making things about women or humans with animals, in relation to animals. Because all the animals are disappearing, and then we won’t know who we are anymore.

BLVR: There’s also so much fantasy in your work. In your 2001 exhibition at the International Center of Photography, “Telling Tales,” you constructed a complete narrative, in photographs, sculpture, and video.You deployed the “Little Red Riding Hood” story, mixed with other myths. The wolf girl, Sleeping Beauty, Eve. You also photographed yourself for it, in a cape.

KS:As a witch.

BLVR: Sometimes people miss the irony and comedy in your work. To make yourself the artist as witch goes back to a medieval idea of women and of creation…

KS:And nature.

BLVR: It’s also uncanny. Your bear embracing the woman from the rear, or your sculpture “The Sirens,” in which a small bird body has a woman’s head, breasts— the body stands on bird’s legs—they’re uncanny and perverse.

KS: The sirens are mythological figures or characters that represent natural phenomena.

BLVR:You said once, “I want to construct a bridge to the unseen.” It’s interesting you didn’t use the word “unknown.”This sculpture fuses unlike elements, man, woman, bird—the unseen. It doesn’t exist in the world, but everything’s recognizable. It gives a sense of a world no one has seen but can imagine.

KS:The unseen, I like that.

V. WIDE SARGASSO SEA

BLVR:You sometimes use the male body: you’ve drawn penises and sperm and made sperm out of glass. But your work mostly focuses on the female body.With all its art-historical and other associations, there must be similar issues to a writer’s, how a female character is read differently from a male.

KS: Yes. It’s read totally differently. I always thought I wanted to go from my experience, although I’m not using myself in my work for the most part, because I didn’t want my work to be autobiographical, so it’s not about me, either. It’s not about my personal life, because I don’t think that’s interesting. But I thought: what if you impose the notion that the female stands in for human? The way you would say “man,”or “mankind”— why couldn’t you use the female that way? I also thought that little of what happens to me in my life is gender-specific. Yet how you experience is gendered, and culturally and personally specific. But most of what happens to you isn’t…

BLVR: How the rent gets paid…

KS: Or maybe what it means about my rent being paid as opposed to a male’s my age means something different but basically you’re just paying the rent.What happens if this is a generic person, and it’s a female person. But obviously, culturally, everything is read differently. People say that I’m a woman artist; in Europe especially sometimes, I get turned into “a woman artist,” with women’s art problems and concerns. I’m just a person. That’s why I make those jokes about preferring that a lot more of my life was very gender-specific in a good way. But it’s not. Most of it is I’m just making art, I’m just working. I don’t see my experience as particularly unique. I also realize that I’m playing with women characters, like my use of Little Red Riding Hood. I would say for me now the biggest influence in my work in the last six or seven years was the novel Wide Sargasso Sea.

BLVR: Jean Rhys.

KS: The idea—which writers do much more than artists—that you could have a character with a certain iconography and attributes that surround it and history, then take it out of its narrative. Like the way the Virgin Mary sits when she sits in a chair holding Jesus, that really comes from Egyptian sculptures of Isis with Horus. Images move around and iconography moves culturally.

BLVR: Rhys is one of my favorite writers.

KS: That book left such an impression on me. I had never thought about taking a character and subverting it, subverting the meaning of one story with another, as she did Jane Eyre. I liked that about “Little Red Riding Hood”; in some versions the woman comes out of the wolf, or the grandmother and the girl—the butcher cuts them out of the wolf, then the grandmother and the girl come out of the wolf. What if you take that image, a woman and a girl born out of a wolf? The wolf becomes a big vagina, covered with blood, a virgin birth out of an animal.

BLVR: [Laughs] A not-so-immaculate conception.

KS: I made a large print of a wolf on the bottom and a woman and a girl coming out of it, in which I made portraits of myself, but I realized: it’s the same position as the virgin on the moon, often a crescent moon was placed at the bottom of her feet, or like Venus on the half shell. There are lots of sculptures and images that exist with a risen body, a vertical female body rising out of a horizontal space.

BLVR:Verticality makes me think about how you configure space.You’ll use the ceilings, floors, walls. It’s not as if you make work for the floor.

KS: No. That comes from my working with papier mâché. I made the Lilith piece, where she’s sort of a fly on the wall, but it was only out of luck and the process. I was making her as a squatting figure, or like a fly or animal. If I was making her more like an animal, that was only because she was of papier mâché and she had no weight. Then I realized she could go on the wall. She could be plastered, taped, wallpapered onto the wall, and be seamless, her and the wall. Like a fly but also something like a sculpture.

VI. UTOPIAN DOLLHOUSES

BLVR:You once made a huge chandelier, which hung low in one room, then in the other room you installed a head way up high in a corner.

KS:That space—Fawbush Gallery—was very theatrical. It’s also my sense that in making shows there’s a kind of theatricality, that a show is like a show. Like Broadway. It’s a kind of theater. Statues are in a room and activated. Even if they’re frozen, dead things, they take up psychic space, they make an interaction, and they make something like a play.

BLVR: It’s really object relations.

KS: That’s true also when you make a show, it’s constructing a kind of utopian dollhouse.

BLVR: Sometimes the figures are on the wall or hanging from the ceiling, sometimes they’re crawling, sometimes they’re on the floor lying in the fetal position.

KS: But that probably does come from church stuff also, because in church you have Christ, you have objects on the wall. More so than in museums: you have pedestal sculpture, you have freestanding ones. Probably sculpture was made, historically, for the outdoors, mostly. For gardens or promenades, for public spaces.Then you have discrete art or shrine art. But they all have taken very specific forms.

BLVR:You said once that you liked an idea you heard about transforming the critic into a fair witness. I wondered, what’s the expectation for the artist?

KS:A little bit of what an artist makes is what is unseen. Lucy Lippard said that art recalls that which is absent.And in a way it forces rupture to the surface. It brings to the surface that which has been neglected or needs attention.

BLVR: So the critic has to pay attention to what’s not there. That art makes possible something that might remain unseen.

KS: But also sometimes it makes it right-in-your-face seen. But I have no idea what critics are doing; I certainly have no idea what artists are doing other than making a kind of physical experiment. Physical. I would say it’s just physical model-making, or making an expression of a human’s curiosity.

BLVR:You’ve also said, “I like making the same image over and over again like making batteries by wrapping copper wire around a core, making power by repetition.” So, repetition creates power. Sometimes I think people fear that repetition in work dilutes it.

KS:They fear that there’s a kind of emptiness to people who repeat. But I think a lot of art-making is a form of devotional attention to something. I think that, because some art—not all art—is somewhat contingent on craft, on knowing something physically in your body and being able to manipulate what you’ve learned physically, so that it takes lots of people a long time. I know that I’ve gotten better at doing things. Actually, for me the last couple of years I’ve been making these silly sculptures because I wanted to…

BLVR: Silly sculptures?

KS: Small sculptures, like doll sculptures and figurines, because I wanted to. Before, I never wanted to make my version of figuration. I wasn’t really interested. I was just interested in moving, manipulating body meaning. But then I wanted to have the physical experience of drawing or making something myself. So they come out in a strange way. But I’m trying to learn. I see that you do learn physically, you can move physically from one material to another, and you’re much more adept in one because of your experience in the other.

BLVR: I was thinking about your attitude toward sculpture and about the differences between classical ballet and contemporary dance, about how Bill T. Jones has dancers without perfect bodies.

KS: It’s very conscious. It’s about trying always to enlarge the field.That the field can fit our lives. Because that’s the thing. For the most part, the culture is smaller than we are, so it’s always that we keep having to expand the possibilities while it keeps contracting. I mean, it moves around, but there are always some parts that contract and some that expand, but where there’s contraction and it hits against your life, then you have to cut, cut, cut, go out there with a machete and try to cut it back. So that you have some more possibilities just because we’re much bigger.We have much more space than our culture acknowledges.

BLVR: Is that what keeps you working? Or what is it?

KS: I think just curiosity. I always think it’s going to end. I’m always convinced I’m never going to have another idea but then I don’t know, and, as I say at the moment, I’m in a very mannerist period.

BLVR: How do you mean that?

KS: I feel I’m going over to forms that I haven’t had experience with but it’s as if I’m at the edge of the table. That my work will change in some way I don’t know. But I always think that. I’m very episodic in my work. I go through periods where I would do this kind of work and this kind of work, then this kind of thing, and there are these things that have longer strings and kind of trail around it. But I see that my work really shifts around. My interests shift. And I have very little control over it. I’m not thinking about what I want to be doing next year. I just see that it changes. Some of it is sparked by reading something, seeing something, getting really curious about a certain form. But it just moves around, and there’s so little control over it. But to me, I just feel I’m at the edge of the table. But I’ve had that feeling before, too.

BLVR:A great metaphor:“at the edge of the table.” Is it your table or are you a guest?

KS: [Laughing] A bystander.