Laurel Nakadate collects men. The New York video artist has made her mark exploring the arcane psyche of a very peculiar archetype—the single man, the rural outcast, the lonely bachelor. As an M.F.A. student at Yale, Nakadate began enlisting older local men who tried to pick her up in intricately staged video projects that mixed voyeurism, comedy, awkwardness, and no small degree of old-fashioned raunch.

In these videos, Nakadate has developed a kind of ongoing visual diary, with the artist herself poised at all times squarely in the frame—posing in her underwear, playing dead, or dancing to Britney Spears. The final products are intensely personal, colored with a childish nostalgia and what might best be described as a life-affirming sadness.

This fall she’ll be taking part in three shows in New York—at the Asia Society, Danziger Projects, and Mary Boone Gallery.

This conversation took place on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, involving a few beers, a cupcake, and an in-depth discussion of the very real differences between exploitation and empathy.

—Scott Indrisek

I. SINGLE-ROOM OCCUPANCY

THE BELIEVER: Before you went to Yale you did still photography at a number of girls’ schools.

LAUREL NAKADATE: I was an undergrad in Boston at the Museum School. I had just moved to Boston from Iowa, and I only knew one person and it was this girl who was going to Wellesley, which is an all-girls school. It’s known for its “prestigious graduates.” I started going to these parties at Wellesley that my friend Lisa invited me to. And I would take this bus from Harvard Square that picked up Harvard and MIT boys—and me—to take us to the party. It was called the Fuck Bus. I’d ride the Fuck Bus with a bunch of eighteen-year-old boys, and I’d have my camera and my video camera and I’d take pictures of these parties, which were sponsored by the school—they were on campus in these beautiful dining halls or ballrooms. Essentially, for four years I watched girls get really drunk on their parents’ dollar and take off their clothes for visiting boys and professors. I watched the whole thing, and that’s where I got my start taking pictures, I guess.

BLVR: You applied for the photo program at Yale, for documentary photography—

LN: I showed up to this photo program and ended up immediately making videos, which were one part documentary and one part this constructed narrative that came out of my head, sort of spur-of-the-moment narratives with these men that I met.

BLVR: Were you doing that from day one, making videos involving strangers?

LN: Yeah. I got to Yale and I didn’t know what I wanted to photograph. I’d just finished the college-girls documentary. I knew I was still interested in looking at people, I knew I wanted to put myself in a world I didn’t belong in because I liked the friction of feeling like I didn’t belong—the terror of not knowing what’s going to happen next in a room of people I didn’t know how to interact with. I noticed when I first got to New Haven that a lot of [older] guys were really fearless about coming up to me on the street and talking to me, and that was something that I had not experienced in Boston. New Haven is a really strange town—there’s really two parts to it: one part is Yale and the other part is New Haven. I started talking to these men and I’d take their phone numbers.

BLVR: Where were you meeting them?

LN: I’d meet them everywhere—in parking lots, on the street, in the grocery store. The most memorable one was the guy I met in my apartment building. I was getting out of the elevator and I accidentally dropped my keys down the elevator shaft. I asked him if he would let me borrow his phone to call the super to try to get the key to my apartment, and he said, “Actually, I have a copy of your keys in my apartment.” Apparently—I don’t know if I believe this story or not—the super had entrusted him with keys so that he could let people in when they got locked out. We started talking and I told him I was a photographer. He said, “Well, maybe you can come over and hang out some time.” I said, “I’ll come hang out, but can I take pictures?”

BLVR: Which obviously is not that much of a turnoff… was he an older guy?

LN: At the time I was probably twenty-two and he was probably fifty.

BLVR: So this wasn’t Yale University housing.

LN: No, I was living in an SRO off campus. An SRO is a single-room occupancy, which is essentially for transient people—people who want to live alone in a one-room studio… a very small living space.

BLVR: What was the first time that you invited someone in?

LN: The elevator guy was probably the first one. He’s been in a lot of my videos. He’s sort of my recurring character. He’s in the birthday-party video.

BLVR: How did that project come about?

LN: The birthday-party video is one of the first that I made with strangers I met on the street. I wanted to make believe with them, to play pretend. These are men who live by themselves, who don’t have anyone to care for them or anyone to care about. I wanted to put them in a situation where they were really in over their heads or out of their depth or just where they felt uncomfortable and didn’t know how to deal with what was happening. The one thing that single men don’t know how to do is have birthday parties—they don’t have children, they don’t have anyone to celebrate with. I showed up at their houses in a party dress with a birthday cake and I asked them to pretend that it was my birthday and to celebrate my birthday with me. I’d have this birthday cake and I’d set it down on their kitchen table and ask them to sing to me. So they sang “Happy Birthday” a cappella and we had cake together.

BLVR: Did they know it wasn’t actually your birthday?

LN: Yeah, but I think that sort of added to it, because the fact was that it wasn’t really my birthday but I was pathetic enough to really want a birthday party. I think I may have also said something to them like “No one ever remembers my birthday. Will you celebrate it with me?” What I thought was really touching was that these men had no way of knowing how to celebrate a birthday party with a girl, but they tried so hard and they wanted so badly to make it work for me.

BLVR: Had they been married? Had kids?

LN: One of them had been married but his wife had ended up “accidentally” tripping in a hotel room and breaking her head open on a glass table.

BLVR: While he was there?

LN: He said he wasn’t there, but I don’t really know. The story changes depending on when I ask him. Most times the story is that she tripped on a rug and fell on a glass table and broke her head open.

BLVR: When you’re meeting these guys, in the parking lot or the grocery store, are they approaching you? Are you putting yourself out in some way that makes it look like you want to be approached? What’s the normal scenario?

LN: In general, I wait to be approached. I want to be the one who’s hunted, I want to be the one who they take interest in—because if they’re not interested in me, they’re probably not going to be interested in being in a video. I also like the idea of turning the tables—the idea of them thinking that they’re in charge or that they’re in power and they’re asking me for something and then I turn it on them, where I’m the director and the world is really my world.

BLVR: How do you frame it?

LN: Usually they either ask me out or they ask me what I’m doing.

BLVR: Do you tell them you’re an artist?

LN: It varies. Usually I just say I like to take pictures.

II. HELLO KITTY BOOM BOX

BLVR: So after the birthday-party piece—

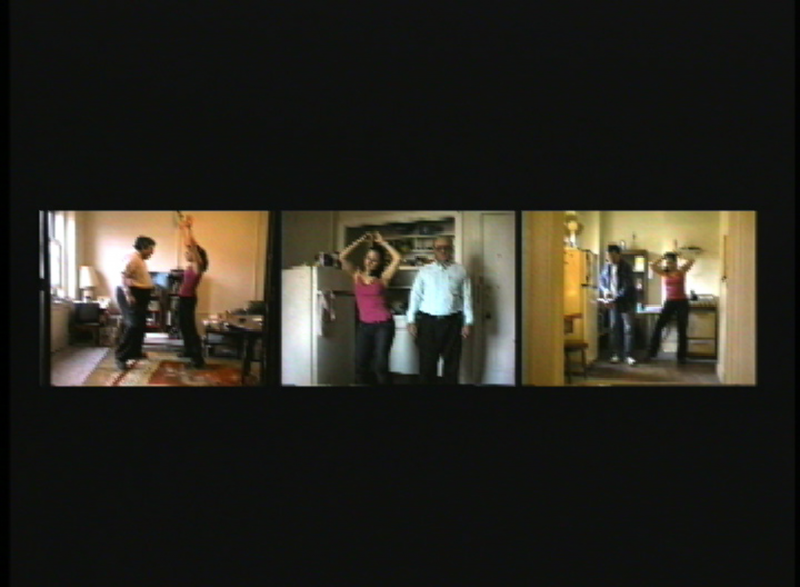

LN: The next piece I made was a dance piece. At the time, Britney Spears’s “Oops, I Did it Again” was the No. 1 single on America’s Top 40. I showed up at these men’s houses with a boom box—a pink Hello Kitty boom box, to be specific—and Britney’s “Oops.” I told them that I had memorized the entire song off MTV, which I had. I downloaded the video and memorized her choreography. So I asked them to dance with me, and we danced to the song from start to finish. Three different men. I actually shot about five, but ended up only showing three. I’ll shoot a lot of stuff that I don’t show because I feel like even if you experience things and shoot them, you don’t have to show them. Some things I’m just keeping for myself.

BLVR: For the B sides.

LN: For the dark side!

BLVR: In that video, we see a real-time triptych of you dancing with three different men. The guy in the middle frame, if I remember correctly, isn’t dancing.

LN: He’s moving in his own way.

BLVR: Did you ask him to dance?

LN: He was dancing. Really slow.

BLVR: He looked like he was trying as hard as possible to show no movement.

LN: I think he wasn’t actually dancing, but maybe in his mind he was having some sort of dance experience. I asked him to dance. It’s more uncomfortable to be dancing around someone else who’s not dancing.

BLVR: The guy on the left panel—

LN He did a great job. The guy in the middle, he kind of became my anchor. He kept me humble. He’s been a recurring character in my videos. He’s like my Divine.

III. SIX CASES OF THIN MINTS IN ONE DAY

BLVR: So what did you work on after that?

LN: The next fall I started doing some surveillance work where I dressed up as a Girl Scout. At the time I was actually mentoring Girl Scouts in New Haven. I was like a Big Sister, teaching girl scouts in New Haven how to take pictures. I actually was a Girl Scout as a kid. I managed to fit into my old uniform. I had access to a lot of Girl Scout cookies. I put a surveillance camera on my sash, and I went out and sold cookies door-to-door and videotaped people’s reactions. I “passed”—no one doubted I was a Girl Scout. Again, it was about going into places I didn’t belong, other people’s homes, wanting to have people react to me. I was playing it dead straight. I was actually selling the cookies on the spot. I think I sold about six cases of Thin Mints in one day. There was one guy who said, “Ohhh, you look sooo great in your uniform today. You look sooooo great.”

BLVR: What happened to that video?

LN: I feel like it was student work, but something I needed to do to get past the fear. There’s a certain rush that comes from making these pieces, because I’m putting myself in a situation where I really have no control: going out there and being at the mercy of whoever opens their door to me. I think it’s a really good thing to put yourself in a situation where you feel really uncomfortable because I think things can come out of that discomfort.

During that same time, I worked on a project where I’d record the outgoing messages on men’s [answering] machines. This was before everyone had cell phones, so I was calling a lot of people’s homes. The thing about giving out your landline number—which is not something I’d recommend anyone doing—is that you can do a reverse search to find the address. So I found where these guys lived, and I’d spend an entire day following them. I’d sit across the street from their house and wait until they came out in the morning and then follow them. I never did much with the project but I felt like it was something I needed to do. I’d follow them and take pictures, like surveillance pictures. They never knew or found out. Some of them had jobs, sometimes they’d just be hanging out, driving around. There are a lot of grainy pictures from far away of men just sort of living, doing their man thing.

IV. LOLITA, ON HER OWN

BLVR: So why did you move to New York after grad school?

LN: I’m a girl from a small town in Iowa, so where else was I going to go? I moved here in 2001. In May. I didn’t really know what I was going to do. I think I was just naive enough, young enough, and dumb enough to think I could move to NYC and make things. I found a lot of guys in New York who ended up in my videos, but I keep finding myself drawn to the Midwest, because everything makes more sense there. The kind of men that I find out there are more familiar to me. There’s something more humble about them, more open. Maybe they’re familiar because they’re the men I grew up watching.

I also like videotaping men who live in towns that are off the beaten track. Not only do they live these lives in a room by themselves with no family but they live in a city that nobody cares about. Anyone in New York City is not that far off the beaten track. I shot some video with a guy in Nebraska. I do a lot of my work going on road trips—my little version of Lolita, only Lolita’s on her own, taking herself on a trip. So I found this guy in Nebraska walking along the side of the road. I started talking to him. It turned out his parents had both died in the last month and he was living in this house by himself and I went over to his house and it was clear that he hadn’t left the house in weeks and weeks. A stockpile of shit all over the place. There was something lovely about this secret life in the middle of nowhere, with everything you need in your home and you never have to leave the house. Things might not get better but they might not get worse. There’s something sort of beautiful about that.

BLVR: Shortly after you moved to New York, though—

LN: Yeah, the video where I’m standing on my roof in the East Village on the morning of September 11. The twin towers are smoking behind me and they’re about to fall, and I’m standing there staring at the camera in a Girl Scout uniform. At the time I was doing all this work around the idea of scouting, going out into the world and discovering little tragedies and how they meet the world’s larger tragedies. I was making all these videos where I was framing myself physically in the context of things that were happening behind me. The morning of September 11 I woke up and went out to my roof and that’s what I saw. It was a way of trying to make some sense out of that morning. I heard the planes hit. I went up to my roof, and all my neighbors were there. That was just what happened that day. I wasn’t trying to make some political statement.

BLVR: And you’re looking at the camera the whole time.

LN: Yeah, I don’t turn. It wasn’t about trying to critique. We didn’t even know what it was at that point—9:45, 10 a.m. on the morning of September 11.

BLVR: Stylewise, it’s similar to the clips where there are fireworks behind you.

LN: It ties back into this feeling of wanting to watch things fall and the moment before they break. Fireworks are that way for me—this lovely thing that blows up and is gone. It all goes back to this desire to record things before they disappear—the original reason we take pictures, right? To record things before they disappear. That’s what September 11 was for me, to record something….

BLVR: What was the reaction?

LN: People sent me hate mail saying, “What right do you have to show footage of that day?” When I received those emails all I could think was that they weren’t looking at the video, they were having a knee-jerk reaction to someone using footage from a day that’s very loaded.

BLVR: There was also a moratorium on that footage. That’s why it’s so affecting—the viewer isn’t used to seeing it.

LN: I also think that people don’t want to imagine that anyone made anything that day that was anything but straight documentary, and I think people have a problem with me having made art on that day. Because somehow art doesn’t take place in tragic moments.

BLVR: It forces us to think about when it becomes possible to artistically handle that day and those events. Creating the work so clearly in real time—

LN: —is extremely problematic. When I showed the piece, people said, “We aren’t ready to see images of that day in an artistic context.” But I don’t buy it. Why do we need to wait to talk about a thing? It’s been five years. I’ve sort of learned not to worry about what other people are going to think about the things I make, because someone’s always going to have a problem with me.

V. LOVE HOTEL

BLVR: What about Love Hotel?

LN: A love hotel is something we do not have in America, which is a real problem because it would be a really beautiful thing to have. They’re hotels in Japan where you can rent a room by the hour, because there’s a lot of people who live with their parents. They live in small spaces; it’s a way of going to a hotel with your boyfriend or girlfriend. Some of them are really nice, some of them are super trashy. I’d always been drawn to the idea of this one-hour time period where you could just go and be in this other world.

I had been dating this guy, and we’d always talked about going to a love hotel, but the relationship ended badly, so I went to Japan by myself with absolutely no plan, and I ended up staying in love hotels for a week. It was a really strange thing. I’d never been to Japan. The great thing about a love hotel is that you show up and there are pictures of the rooms, you select the picture of the room you want, put in a credit card, and it pops out a key for you. Most of the time you don’t have to interact with a clerk. They like to keep their sex anonymous there [laughs]. I’d go into the rooms and pretend that I was there with my boyfriend and pretend the relationship hadn’t failed, pretend that we were there together, pretend that we were still in love, pretend nothing bad had ever happened. You know. [Laughs]

BLVR: It made sex seem kind of hilarious when you ran through all of those positions, minus the other person, totally deadpan.

LN: I got that idea from Nightmare on Elm Street—there’s a scene where this cheerleader girl gets slashed by Freddy Krueger in her bedroom. But all we see is her being thrown up in the air, slashed, and then writhing around by herself on the bed. I always thought there was something so beautiful about getting attacked and turned on by something we can’t see. When I was in these love hotels, all I could think was “I want to get attacked and turned on by something I can’t see.”

BLVR: Attacked?

LN: You know, attacked in the sense of physically moved. [Laughing] That’s going to sound so wrong. So wrong. I guess—a lot of my work stems from things that I see in pop culture, MTV songs, movies.

BLVR: OK, so Love Hotel.

LN: What else is there to say? I went to Japan, I pretended to get fucked in rooms I didn’t belong in, and I came home. It was a long flight!

BLVR: You didn’t do any sightseeing?

LN: No. I think I might’ve sat at a park at some point and fed some birds. The whole thing was just like a relationship—you go through a lot of trouble to basically writhe around a little, and then you go home by yourself.

BLVR: Cynical.

LN: Or just lovely! I think my work is optimistic—as much as it is pathetic and funny and sad and ridiculous, at the end of the day it’s about the hope that something will go right, and the constant wishing for a world where things might start to make sense.

VI. MAGIC REALISM

MIXED WITH SLAPSTICK

BLVR: In meeting these guys, has there ever been a negative experience, a line crossed?

LN: No. I feel like the men who end up in my videos, their biggest crime is being lonely. They’re not violent, they’re not scary people, they’re just men who keep to themselves and have a hard time being social. I’m always out there by myself, I go into stranger’s houses. I did a project where I went and walked around a truck-stop parking lot and videotaped myself dancing with men in the cabs of their semis. I definitely am taking risks, but I think something really great can come out of putting yourself in an awkward situation. A lot of people think that the work is about mocking or making fun of things, but a lot of it is about discomfort and making myself as uncomfortable as the men feel, or putting myself in a situation where I’m revealing my loneliness as much as they’re revealing theirs.

BLVR: There’s enough silliness to it—

LN: If anything, I’m making fun of myself. As much as I talk about the work starting because I wanted to investigate lonely lives, it’s as much about slapstick and folly and the ridiculousness of trying to create anything. The ridiculousness of showing up anywhere and thinking anyone will give you attention.

BLVR: How is the relationship off camera? What else goes on that you don’t videotape?

LN: It’s case by case. Most of the time, I won’t hang out with them. I really want the relationship to be something that is created on camera. There’s a power that comes from a relationship that’s purely based on make-pretend for the camera, this dynamic that wouldn’t exist if I hung out all day with them and it became casual. There’s this heightened moment that happens that I would otherwise lose.

BLVR: What are you looking for in a subject for a video?

LN: I guess the main thing I’m looking for is someone who seems like they have a space in their life for me. Maybe it’s the same thing you look for in relationships. Looking for someone who has a space in their life or who can look at you for longer than a minute. A lot of people have said that the main thread in my work is loneliness or just wanting to create a world with someone who doesn’t really have much in their life, so maybe I’m looking for someone who’s lonely and wants to try to create something with me.

BLVR: Why is it that you are usually either playing dead or wearing very little clothes?

LN: The lack-of-clothes thing is about putting myself in an embarrassing, disarming situation. If I’m barely dressed in these videos, (a) it makes them a little bit dirty, (b) it makes them a little bit pathetic, and (c) it disarms people to the point where they think that I am not going to be able to control any situation and am probably pretty vulnerable, which nine times out of ten I turn it around so that I might be the one half-dressed but I’m not going to be the underdog.

BLVR: What about the videos where you’re in these scenes where you’re dead and these guys come in…

LN: Where You’ll Find Me. I shot them out west. There’s one where I pretend to get electrocuted. The thing about death is that it’s embarrassing. No one wants to focus on it for very long. We’re happy to talk about sex all day long but no one wants to talk about the moment where it all ends. I find some comfort in running through the worst-case scenario in my mind and seeing how it’s all going to go down. Death is sad, yes, but there are some great laughs you can find there. I can’t even remember what it was, but I was watching some action movie the other day. I was thinking about how organized crime is sort of like magical realism mixed with slapstick. You see these men blowing each other apart with guns, and it’s sort of this beautiful magical realism mixed with this ridiculous Laurel and Hardy comedy.

BLVR: They’ll never get killed.

LN: Yeah. There’s got to be a place for slapstick and untimely death and sad sex. There’s got to be a place for it!

BLVR: I think there is. You’ve got Faces of Death videos.

LN: Dude, Faces of Death is old-school. I love it.

VII. A FABRICATED WORLD

BLVR: Let’s talk about the new work, the road trip you took for Trouble Ahead, Trouble Behind.

LN: I got on Amtrak for thirty days last November. You can buy these rail passes where you can take Amtrak for thirty days in the U.S. and Canada. I took the train from New York down to New Orleans, Chicago, Memphis, Seattle. Mostly I ended up sitting in hotel rooms by myself and staring at myself and making videos about being lonely. I had made all this work about people I don’t belong with, and now I’m going to make some work about places I don’t belong. It’s just me. I took pictures of myself throwing my underwear off the side of a train and pictures of men I met on the train. I went up to the American Gothic house, the house that Grant Wood used as the setting for the painting, and I pole-danced in front of the house. It’s thirty days where I disappeared from the world and I think that the video and the show that came out if it was about travel, being in these Edward Hopper-esque hotel rooms by myself. It’s always a problem—you’ve got to figure out a place to put your body. You’ve got to wake up in the morning and deal with the fact that you have this body to lug around. It was thirty days where I didn’t have to worry about that. I was just cargo. The pictures were sad—in the best way.

BLVR: Since you’re in almost all of your work, I don’t think it’s unnatural to read it autobiographically, or at least to make that assumption. How much of what you’re acting out is actually you? How much of it is an expression of some small part of you?

LN: I think it’s about 10 percent me and 90 percent fiction. Although I get a lot of ideas from things that have happened in my life, I see the final product as a place where my imagination meets my experience. What I love about photography is that nothing is really as it seems. Although I use myself in my videos, I really see myself as a character. When I look at myself, when I sit and edit, I never think, “That’s me.” I think, “This is a character, and how do I edit this to tell a story?” I’m more interested in the idea of role-playing in general than the idea of role-playing in art. I like the childlike quality of making pretend or the optimistic idea of pretending something’s happening when it’s not.

BLVR: Because you’re so involved in the work, it’s tempting to think, “This girl wants to kill herself, and she’s a nymphomaniac!”

LN: One of the problems is that I’m the writer, director, and actress in all of this. Normally an actress would not be bound to any part she plays, and people would always know it’s a made-up character. People think I’m deeply implicated in it. I believe that I am some sort of fiction writer and I’m using myself in the work because I’m the person I’m most convenient to use!

BLVR: People don’t assume that with written fiction. The first-person “I” in fiction could be a skinhead, racist, misogynist bastard, and the author wouldn’t necessarily receive hate mail.

LN: As people who make things, we have the ability to think of the most vile, awful things we can imagine, but it doesn’t mean we believe those things. I allow myself to go places in my videos that I would never go in my real life. And I think that there has to be that place where you can create and not have to be living it in real life. It’s one of the problems in my work. It’s a fabricated world.

BLVR: It complicates it a bit that you’re dealing with other “real” people—you’re not hiring actors and writing a script.

LN: Yeah. But I’m interested in that hybrid—the place between the real world and my imagination. There’s a friction that’s created between the things we imagine and the things that exist. A lot of directors use that approach to filmmaking. Godard does that all the time, where he’ll feed lines to the actors as they’re happening. Characters will be created on the fly. There is a history of doing this, but people want it to be one thing or another; they want it be fact or fiction.

BLVR: When you look at the pictures of these men, your knee-jerk reaction is to think there’s some kind of exploitation at work. On video, you’re obviously having a good time with these guys, and there’s a clear sense of respect. And it seems like there’s also something that you’re looking for in the relationship.

LN: When I made the jump from photography to video—when I first started making these videos—it was because one of the big criticisms of the photo work I did was “Where are you in this? You’re just making fun of these girls, documenting every pile of vomit they produce and every time they take off their underwear in their dorm room, but where are you in all of this?” At the time I was just sort of standing at the edge, being a big loser at these parties with my camera. Part of making that jump was putting myself in the work. Yeah, a lot of people look at the work and they think that I’m just being evil or pointing the finger at these pathetic souls, but I’ve always seen the work as trying to make the connection with men who no one really spends time with.

When I was really little I remember driving by a sort of makeshift tent at the edge of these woods in northern Iowa, near where Buddy Holly’s plane crashed. I was on my way to summer camp. I had all my belongings packed up, and we drove by this makeshift tent. I asked my dad what was going on and he said, “That’s where hermits live.” And I was like, “What’s a hermit?” And he said, “It’s a man who lives by himself and doesn’t really have anyone.” And I remember looking at my little suitcase on my way to summer camp and his little tent in the woods and that we were kind of the same. I was going out on this adventure by myself with my pink Velcro sneakers, and he was out there in his little tent. It really affected me. I was about seven years old. Every time I saw an older single man by himself after that, all I could think of was that little sad tent in the woods.

So that experience of seeing the hermit’s tent inspired me to become a hobo clown in fourth grade. I took clown lessons because my goal in life was to be a professional clown. I learned how to ride a unicycle, I learned how to juggle. I took on this alter ego. I became a hobo. The costume was a men’s suit jacket with a fake beard on my little fourth-grade face. I walked on stilts. I was obsessed with this idea of people who live by themselves and didn’t have to deal with anyone. So I guess this has been a theme in my work since about fourth grade [laughs]. Not to defend my intentions in going and hanging out with these men but I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for them.