Laylah Ali was born in 1968. It was a year marked by cataclysmic change: movements, invasions, offensives, assassinations, and a student demonstration-turned-massacre in Mexico punctuated by black-gloved fists raised in the air at the Summer Olympics gathered like storm clouds over the optimism of the previous year. Perhaps I’m forcing connections—maybe it’s just coincidence that Ali grew up to create an exacting visual art out of social and political commentary using similar gestures, but it’d be folly to chalk up the reflective precision of her paintings to her schooling alone.

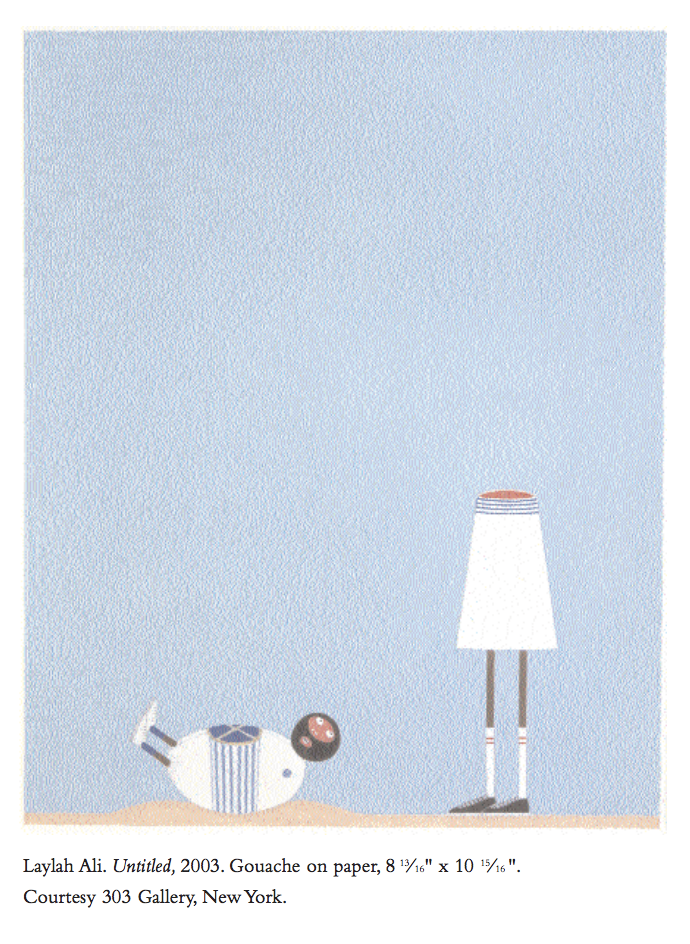

Ali earned an M.F.A. from Washington University in St. Louis in 1994, and studied at the Whitney Independent Study Program in New York and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. Her fascination with weakling superheroes, regimentation, alliance and betrayals, ambiguously tense environments, and, curiously, dodgeball, led to the Greenheads, a series of more than sixty paintings Ali began exhibiting in 1998. These figures, rendered in meticulous detail, are expressive, brown-limbed, razor-thin androgynes, all related by their eponymous green heads yet often segregated by colorful uniforms, accessorized by belts, masks, or rank-denoting headdresses. One such figure, in headdress and white tunic, might be a boss scolding three alternately incredulous, defiant, and apologetic-looking underlings for a botched job, or a survivor pointing out captured war criminals accused of heinous acts.

Ali’s Greenheads has sparked a good deal of debate, from discussions of race, class, and political content in visual art to conversations about the richness (or legitimacy) of genre-crossing between fine art and illustration. Always, though, people ask: how are we supposed to know what these paintings are really about? Though reminiscent of tribunal scenes, war games, comic books, and the absurdist stagings of Adrienne Kennedy and Samuel Beckett, her paintings are free of the slogans, captions, and loaded titles we might expect from such politically charged work. Viewers and curators alike are left to mine their own perspectives and imaginations for answers, and, fortunately, they enjoy ample opportunity to do so. Ali has been featured in solo exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, (which commissioned her to produce a wordless graphic novelette—which, like much of her work, is untitled—in 2002); ICA, Boston; MCA, Chicago; Contemporary Art Museum, St. Louis; and MASS MoCA, among others, as well as showing her works at such exhibitions as the Venice Biennale (2003) and the Whitney Biennial (2004). She is also a featured artist in the PBS series Art: 21—Art in the Twenty-First Century, broadcast beginning fall 2005.

Now that the Greenheads has firmly established her vocabulary as an artist and thinker, Ali has taken her art not just to the next stage, but into the third dimension. For the Kitchen performance space in New York, she collaborated with choreographer Dean Moss on Figures on a Field, which reinterprets, with dancers and audience, the scenarios of her earlier paintings, and the gallery experience. She’s currently working with portraits, manipulating this canonical form by creating intricately marked paintings of imaginary personas instead of actual people, to convey narrative.

Ali is on sabbatical from Williams College, where she teaches, so I had to rely on various inexpensive methods to reach her in her studio in Melbourne, Australia. She was preparing for a solo show at Melbourne’s Gertrude Contemporary Art Spaces, as well as a group show, The Body. The Ruin, at the University of Melbourne’s Ian Potter Museum of Art.

—Tisa Bryant

I. “AUSTRALIANS SEEM LESS PRUDISH THAN AMERICANS— MUCH MORE NUDITY ON REGULAR T.V., EVEN PENISES.”

THE BELIEVER: How is Melbourne as a place to work?

LAYLAH ALI: I’ve been looking for burglars in a burglar-ridden city. I’m drawing imaginary portraits. I’m trying to figure out if it is possible for me to feel comfortable here.

BLVR: How do you look out for burglars in a burglarridden area? Is Melbourne known for that?

LA: I’ve been thinking about it because the house I’m staying in was recently robbed twice within a few months. Melbourne seems to have a drug-related crime problem—lots of house break-ins or “home invasions,” as I think they call them here. I’m told by actual Aussie police officers that I should not fear these thieves because they are only drug addicts and not harmful people. Having been raised in our calm and reasonable U.S.A., I was of course moved to ask if the burglars would be violent if encountered. I was told that they are unlikely to have guns—but knives are not uncommon. So they are allegedly not to be feared, but you shouldn’t really get in their faces. The culture here certainly has a violent aspect to it—the news is obsessed with the same tawdry murders that plague the U.S. media. But Australia seems less fearful and paranoid than the U.S.A. Whereas the Americans engage in fear as a finely tuned hobby, Australians would rather spend that time enjoying themselves. I think it’s preferable—the lack of group fear—but sometimes it seems a bit like wishful thinking. And my American conditioning is all wrong for the casual Australian attitude toward this and most things.

BLVR: The lack of group fear in response to violence and crime does sound preferable to what we experience in the States. Here, we gate and alarm and arm ourselves. What do people do in Melbourne? Do they talk about violence in their local culture, or do they blow it off?

LA: I don’t think Australians would say that they have a violent culture. When compared to the U.S., Melbourne probably isn’t that violent, but that’s the problem—the United States is such an extreme example. When I’m here, I’m very struck at times by how similar Australia is to the United States, primarily with the “free market gone wild” attitude that prevails. And of course the end less murder shows on TV. CSI this and that, Law and Order over and over again. Every time I turn on the TV, I’m seeing a corpse (usually female) being pointed at and prodded. That’s the same. Australians seem less prudish than Americans, though—much more nudity on regular TV, even penises.

BLVR: And that term, “home invasion,” from the perspective of an indigenous Australian, must take on a completely different interpretation.

LA: White Australia has done, over the years, as complete and disturbing a job at minimizing the impact and presence of the Aboriginal people as the U.S. has with Native Americans. Australia is a very segregated society in the cultural sense—and it’s very hard to find gatherings that are integrated. Australians of Greek and Italian descent are considered as proof of diversity here.

BLVR: I see. With your drawings in mind, it’s rather fitting to be discussing crime and burglars, subjugation and global terror. In my imagination, you’re at an open window, keeping an eye out for your own masked figures.

LA: It’s more like I am sitting in a rocking chair on the front porch with my shotgun. Deputy Ali come to Australia to fight crime. It’s eating into my studio time.

II. “I THINK I NEED TO DISAPPEAR A BIT IN ORDER FOR THE VIEWER TO ENGAGE MORE FULLY.”

BLVR: I’ve noticed some shifts in your recent work, away from the more angular, exacting tableaux of the Green heads series and the graphic novel you put out, to drawings that feel softer, looser, and somehow rounder. A figure caught in an elliptical ball of its own body; painted portraits; large, fluid, decorative heads. Are these new avenues for you or a continuation of pre-Greenheads work?

LA: I am drawing quite a bit now after working on paintings, which are physically demanding. But yes, over the past year, I’ve moved away from the group scenes of figures and focused more on individual characters. The last group of paintings I did were more like classical portraits—except that they were all fictional characters, straight from my head to the paper. Instead of stripping things down, lately I’ve been swaddling them up until you can hardly see them anymore. I’m feeling the need to look more closely at these figures that I keep torturing and putting through the hard paces. I think all artists go through periods when they question their practice but still need to keep in touch with the process, and I’m going through that right now. I possess an internal rage that was overwhelming when I was a kid, but through the years it’s become neatly boxed up into a corner of my psyche, periodically firing its way into my life. The Greenheads series was more palpably connected to that rage. That series often operated on a sort of rage/despair/depression/stasis continuum. Part of my process for that series was engaged with stamping and shaping and refining the rage until it was like an evil seed in the work overlaid by all of this control. I think I’m trying to see now what other notes I can hit in the work and still have it resonate.

BLVR: A friend said to me yesterday that the artist always works with the body, not just the body, but his or her own body. That that’s what being an artist is. And yet, in the earlier series, your particular rage, coming out of your specific person, body, psyche, has such a representative, almost generic, look and feel, in terms of the violence we witness or enact as individuals, as well as daily, state-sponsored, public violence.

LA: I’m not sure that my personal rage or anger needs to resonate in the work. It does fuel my need to make the work, to engage, to destroy, rebuild, keep at it. I think what I’m trying to do is to see what happens when something so seemingly dead-ended as rage becomes part of a process, a meticulous process where it becomes fused with other strains such as depressive impulses and actual ideas and questions about the world we live in—to see what this stitched-together creation becomes. So the anger becomes an important part of the process but not necessarily the outcome. My body definitely undergoes the stress and tension of working on the paintings, but that tension is directed into the figures and their exchanges. I really wanted to resist any easy connection to the artist—people always want to go there, to the pathology of the artist, rather than examining themselves. I think I need to disappear a bit in order for the viewer to engage more fully.

BLVR: If rage is part of your creative process, what noise, what sound, does it have for you? If you could attribute a sound to the making of the Greenheads and other group scene drawings, what would it be? In sound/feeling, how do the portraits compare?

LA: My first idea is that they are absolutely silent, even though my studio is filled with noisy music when I make them. But their world is sealed off, separate, special in some ways, because of the vacuum. So the sound of my studio is blaring, constant music or news. But I don’t associate sound with the world inside the paintings or drawings.

III. “BEAUTY IS PERHAPS EASIER TO FAKE, SO MAYBE THAT’S WHY I DON’T LOOK THERE AS MUCH.”

BLVR: What about beauty? Did you encounter a lot of “beauty ideology” in school? Is it a concern, a factor in your thinking or process?

LA: In graduate school, it translated into repetitive discussions about formal concerns. That’s the great escape from meaning—you can describe a line as powerful, delicate, frantic, whatever strikes your eye visually—but not talk about the line being a noose. So beauty is not a word I think about in relation to my work. Beauty has been corrupted by being thought attainable at any cost, so it’s not useful to me. I am interested in damage.

BLVR: Are you in your studio now, with some appliance blaring today’s news, tomorrow’s and next month’s news, about the people of our Gulf states?

LA:Yes, I’m watching coverage here, reading stuff online. I am not surprised by the government reaction, but it still makes me sad and furious. As I said to a friend here, what I see playing out there confirms everything I’ve witnessed and experienced in the United States, but there is something about American mythology that still tricks me into believing that I might see a turnaround in my lifetime… thus the fury? I am reading Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, by Eric Foner, an amazing history book, and the things that still hold true in 2005 when compared with the end of the Civil War are stunning.

BLVR:Talk about continuums.And yet you’re hopeful, you maintain a kind of optimism in everything you’ve said so far. You’re waiting to be surprised by some profound and positive transformation in the way we treat each other.

LA: Well, yes and no, but maybe more no. Each day is still accompanied by the nagging question, “What Is All This?” Sometimes that leads to a sense of wonderment and sometimes to a sense of dread.

BLVR: OK, but isn’t the beauty/damage dichotomy hopeless, in how they complement each other? I’m thinking of photojournalism, how horror is made to look horrible, and yet it’s captured so perfectly. Perhaps talking about beauty in photography is different from talking about beauty in drawing and painting.

LA: Yes. For instance, the New York Times had, on its

website, photos of the devastated landscape from New Orleans, and the headline was “Storm paints damage on a wide and eerie canvas”—they obviously couldn’t put any dead bodies in those pictures. They were all the artsy shots. The plastic-surgery shows on TV are just further along on the continuum. Formalist, modernist concerns have become an endpoint, a way to refer to what we see by just referring to what’s in the frame. Discussion of light and color and composition—or nose, mouth, breasts, chin in the case of plastic surgery—have degenerated into a technical language rather than one that helps build meaning, which is what the first modernists were trying to do. But beyond that, beauty and damage are all about where the exterior meets the interior—it’s one of the most important boundaries that exists. And so we look to that place for some sort of truth about what exists under everything that we see. Beauty is perhaps easier to fake, so maybe that’s why I don’t look there as much. Damage attracts us because it is a kind of language that is indecipherable and usually not taken on willingly. It takes the form of the inside seeping through to the exterior, and I want it to mean something, but I think, ultimately, it just is. It doesn’t add up to any truths. I like the idea that people persevere, that damage can motivate us to do the same, or struggle not to. Damage as the great debilitator and the great motivator. But still, I don’t think it adds up to an overarching narrative like Overcoming or Enlightenment.

BLVR:What should a piece of art, a painting, a drawing, add up to? Is an overarching narrative a goal for you?

LA:Each piece is a reflection of the time in which it was made—both in a personal and in a larger sense. For a series, I will invest in narrative strands that are of interest, but there is rarely just one narrative that I am following. I think the subconscious is as strong as the conscious in my work. Over time, I look at my own work and see more clearly what my preoccupations were, and I like that the work serves as a record of where my mind went. But that is different from a deliberate narrative that spans the work.

BLVR: Aren’t you also trying to have a conversation with us? Encouraging us to explore ourselves, on and across this boundary between beauty and damage? Or are your subconscious impulses so strong that “having something to say” just isn’t part of the process?

LA: That’s what I mean when I mention the larger sense. The conversation, or questioning, occurs in a more conscious way. It isn’t the same as having something to say like in an interview like this, or in a discussion with someone, where I attempt to deliver my opinions and ideas with some sort of persuasive clarity. I am, in person, very opinionated, but the paintings don’t really serve as a vehicle for those opinions. My work is the place where I explore the questions I have—some of these seem unanswerable. I have described it before as “psychopolitical,” which seems like a term that gets at where the two meet.

BLVR: That’s quite a shifting terrain on which to ground your work, the “psychopolitical,” given the robust nature of your process as you described it, exploring your own questions and concerns, then stepping back to leave space for the receiver of the work.

LA: Yes, shifting terrain, that’s a good way to describe it. Though the images are very pictorially fixed, the ideas behind them are, once you spend time with them, not that fixed at all. I don’t mind that. If I wanted everything to be logical and persuasive, I would be engaging in a different way, like writing essays. I want there to be space for things that don’t add up, that are deadends, that offer hope and despair in the same package. That’s how I experience life—it seems more true to the conflicting ways that many of us experience the world.

IV. “I CAN’T CHANGE MY SKIN TO SUIT SITUATIONS, AND SO IN SOME PLACES IT’S NEUTRAL, SOME PLACES IT’S A PLUS, OTHERS IT IS A LIABILITY OR A DANGER.”

BLVR: In creating the world inside the paintings, are you conscious of a point of entry for a viewer? Once you lay down the background, which until recently was always a sky-blue gouache, do you begin a drawing from the center always, left, or right? Does this create an “entry” or a “door” for the viewer? I’m curious about a kind of mythology of seeing, where a viewer stands front and center before a piece of visual art and “sees” it. Yet if a world has been created, not just an object, the point of entry may well be elsewhere, built in by the artist.

LA: I like to have multiple entry points, though often a facial expression or facial tension is where a viewer will go first. Color relationships can direct a viewer almost anywhere you want them to go first, so using color is useful in that it can direct, redirect, and pull at the corners of any interaction. It’s actually up to the viewer how deep they want to go into the world I created. The picture is very flat, so it requires the imagination of the person looking to fully engage—otherwise that flatness will push out at you and act as a barrier.

BLVR: The concealment of identity also acts as a barrier in your work. I’m fascinated by the way you cover your figures with color, with clothing. It inspires curiosity, maybe because so much of the way we identify people in our culture, building persona, comes from these kinds of exterior marks: configurations of clothing, skin color. The gestures in your work, like finger-pointing and shrugging, or the open-mouthed, wide-eyed expressions, are often our sole link to its interior logic.

LA: We mostly interact with the world based on random, quick, external interactions. It’s very difficult to push past people’s boundaries into some sort of honest exchange, so we spend a great deal of time negotiating signs, symbols, skin, and they become a sort of specious code or shorthand. My work is concerned with both the absurdity of this shorthand and its ubiquity, but also its usefulness in negotiating certain situations or predicaments.There is clearly pleasure as well as danger in the idea of disguise, but disguise infers choice—like you can choose what to wear. But something like skin color gives off all sorts of signs that are not necessarily connected to the person inside the skin. So, I step into a drugstore to buy Q-Tips, but, in certain white environments, like when I visited Batesville, Mississippi, a few years ago, I’m treated like I’ve stepped in to shoplift. I can’t change my skin to suit situations, and so in some places it’s neutral, some places it’s a plus, others it is a liability or a danger. That is a great deal to negotiate. So clothing or adornment becomes a way to direct or shape such readings. To redirect attention. To appear larger than life, or to fit in.