Back in 1594, in the very heart of the period we will be considering in the pages that follow, Sir Francis Bacon, while prescribing the essential apparatus for “a compleat and consummate Gentleman” in his Gesta Grayorum, suggested that in attempting to achieve “within a small compass a model of the universal made private,” any such would-be magus would almost certainly want to compile “a goodly huge Cabinet, wherein whatsoever the Hand of Man by exquisite Art or Engine, hath made rare in Stuff, Form, or Motion, whatsoever Singularity, Chance and the shuffle of things hath produced, whatsoever Nature hath wrought in things that want Life, and may be kept, shall be sorted and included.”

Things that want life and may be kept, indeed. Just over a hundred years later, the young Russian who would go on to become Peter the Great, then age fifteen and summering in Amsterdam, happened into the chambers of the legendary dissector and anatomist Frederik Ruysch and first fell under the thrall of the good doctor’s uncanny collection of bottled fetuses; years later, he would buy the entire collection, bringing them back to the capital he was then constructing for himself, St. Petersburg, as the core of the vast wonder cabinet that he himself had begun compiling.

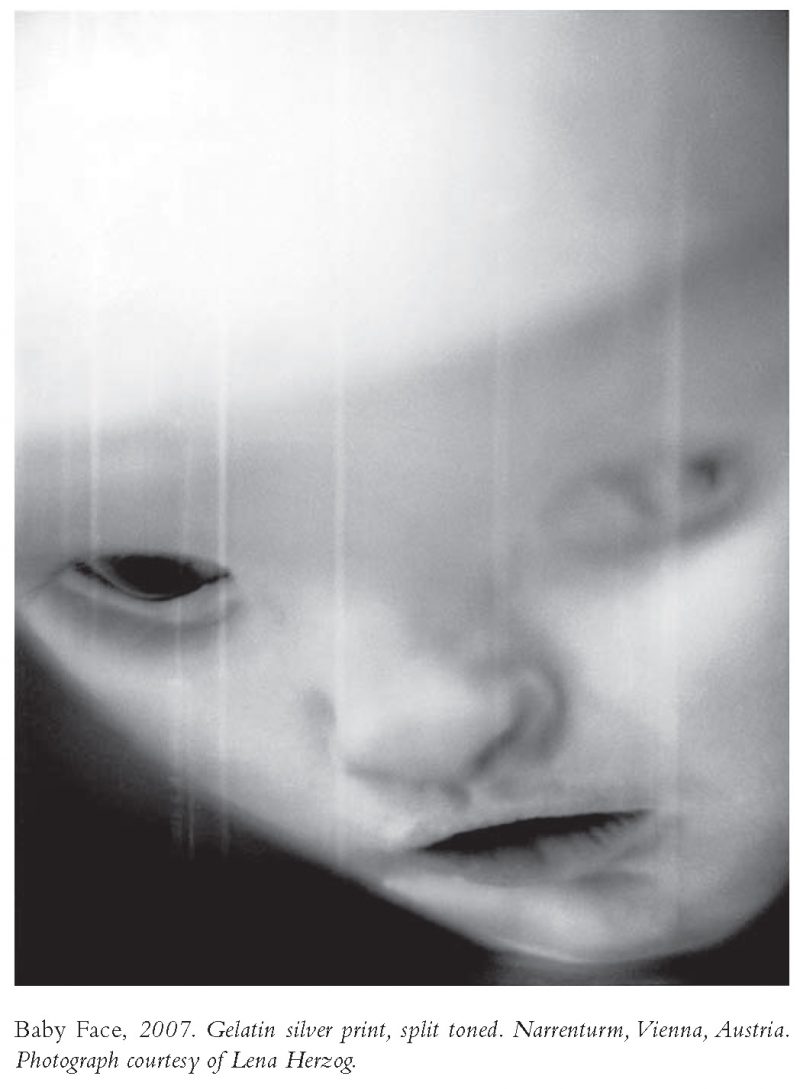

Was it just chance, though, and the shuffle of things, that, almost three centuries after that, brought our protagonist, the then-seventeen-year-old Russian philology student Lena Pisetski, here, stumbling into the dusty precincts of the old czar’s largely abandoned cabinet? Whatever the reason, the astonishing marvels she visioned that silver late afternoon stayed with her. And years later, a now-accomplished documentary and fine-art photographer (in the meantime married to the German filmmaker Werner Herzog), she returned to prize them anew: both those in St. Petersburg, and other similarly flecked wonders in Vienna, Amsterdam, Leiden, Utrecht, London, Berlin, Paris, Turin, Pavia, and even Philadelphia (the incomparable Mütter!).

The resultant body of work—achingly limpid, hauntingly suspended—was recently brought together in a book, Lost Souls, and exhibited, to widespread critical acclaim, at the International Center of Photography in New York, a show that in turn proved the occasion for a conversation between Ms. Herzog and myself as part of the New York Public Library LIVE series, parts of which are adapted in what follows.

Lawrence Weschler

I. A TWINNED SIAMESE TREE

THE BELIEVER: For starters, where did you come from, and how did you come upon these things?

LENA HERZOG: Well, I was born in Russia, in the Urals, what Ian Frazier would call the wrong side of the Urals, the eastern slope—

BLVR: The Siberian side.

LH: That’s where I was born and grew up, and then, when I was sixteen, I traveled back to where my mother’s side of the family comes from, St. Petersburg, which was at the time Leningrad. I studied at the university, at the Philological Faculty. We all knew about the cabinet in St. Petersberg, which was called Kunstkamera, but none of us really ever went there.

BLVR: Where was it, compared to where you were studying?

LH: It’s right next to the Philological Faculty, on the embankment of the Neva River, across from the Hermitage and the Admiralty. It’s probably one of the most beautiful spots in the world. The Philological Faculty is in a blue palace, and the Kunstkamera is in a palace of aquamarine color right next to the Faculty. Our professors used to joke morbidly—especially our professor of Latin—they would say, “Students, if you do not conjugate correctly, we are going to pickle you and send you next door.” [Laughs] That’s how we knew about it, but we never really went. Then one day I thought, Well, as it is so ubiquitous in our slang, I’m going to go next door and look. And as with most of the cabinets, it’s beautiful—it looks like the New York Public Library—marble floors, crystal chandeliers, oak handmade shelves, but instead of books there were these creatures. What I experienced was a true experience of wonder: I felt the ground leave from under my feet, and everything I believed and wanted to believe was immediately emptied from my head. All the comforting thoughts were emptied, and it felt like it was some sort of riddle, and it never left me. You encounter a lot of nice work all the time, daisies and things, and it’s lovely but it’s instantly forgettable. This was not forgettable.

BLVR: So remember it for us: what exactly was it like?

LH: Well, you see, the first day that I saw it, which was twenty-three years ago, when I was seventeen, I saw it not in the electric light, which gives the fetuses a warm, fleshy look. There was a blackout that day; the St. Petersburg silver light made its way through the curtains, through the crystal chandeliers, and it sort of sprinkled this almost Christmas light upon all the jars, making the room appear as a strange and stunningly beautiful place. There was no terror in me at all. I did not experience horror, because when I first saw the preservations, they looked like creatures from another world: completely silver, and like they were shining from inside because of the way they were lit.

By the way, on the way to these rooms of Ruysch’s creatures, you have to go through rooms filled with maps and astrolabes and old barometers and all kinds of gorgeously crafted instruments of navigation. So you were prepared to travel. But you didn’t know whether your traveling was going to be upward or downward or in some completely other direction. You might see, for example, a map that had a fairly good representation of Europe on it, and then next to it would be a dragon, and it would say, “May dragons be there.” As you have said, one of the reasons the wonder cabinets became a huge hit at the time of the Renaissance is because Europe’s mind was being blown away by the Americas.

BLVR: A question that’s often asked is why is there this sudden eruption of a taste for marvel, for wonder, around 1500? It wasn’t there before in that degree, and then suddenly, for about a hundred and fifty years, Europe seems just agog with a taste for marvel and wonder, and it’s partly because of all the stuff that’s coming in over the transom from America—you know, purple parrot feathers, moose antlers.

LH: Dinosaur bones considered then to be bones of giants.

BLVR: Sacrificial urns. Dinosaur bones. I mean, all this—

LH: —tropical butterflies.

BLVR: All this wild, weird stuff is coming in. But the way in which that allowed you to believe stuff that you’d gotten over believing—I mean, if narwhal tusks existed, sea unicorns, why couldn’t unicorns exist? They must exist. In fact, human horns must exist.

LH: Of course!

BLVR: And everything is unsettled. There is a sudden taste for being unsettled.

LH: Absolutely.

BLVR: Could you walk us through who Ruysch was, and what on earth his jugged fetuses were doing in St. Petersburg?

LH: He was born in The Hague in 1638 to a family of very, very modest means. He lived to be almost a hundred. He died at the age of ninety-two. Despite his background, he became a prominent scholar: a botanist, an anatomist, and was even called to be a forensic adviser to the Amsterdam court. When asked why did he switch to anatomy, he said something very interesting. He said botany’s questions were too simple and so were the answers. It is in anatomy where all the riddles lie.

BLVR: That reminds me of something Oliver Sacks once said when I asked him why he became a neurologist. He said, “Well, you know, I could have been a cardiologist. And, I mean, the heart is a really interesting pump, but it’s just a pump.”

LH: Exactly. Ruysch was very much interested in bodies, and at the time he started to do his preservations, medicine consisted of a lot of guesswork: the elbow is approximately over there. The reason for such vagueness is because the dead body instantly decays and becomes very different from a live body, but the moment Ruysch starts to preserve them, he actually can teach, and—

BLVR: Any history of anatomy describes him as the grandfather of anatomy. He is the George Washington, the founding father of that discipline. At the time, people like him were on the one hand doing really weird, strange things, but at the same time laying the groundwork for everything we do today.

LH: One of the things that has to be understood about Ruysch is what an enlightened man he was. When he realizes the ills that were occurring during childbirth, he actually acquires not only the profession but the l icense of a midwife, which was otherwise held exclusively by women. He makes these extraordinary advances in instruments and methods. Not only that, but he strictly prohibits all the midwives to practice any kind of exorcisms. Ruysch demands that the midwives become professional, that they learn what he has invented. It actually becomes a profession because of him.

BLVR: And one of the effects of his being a midwife is that he is present when these strange births happen. He is there for stillbirths and so forth. It’s worth putting ourselves back in the mindset of that time, when there weren’t various intrauterine devices, there was no sonar, there weren’t all kinds of things. You often had very, very strange fetuses that would go to term, sometimes with fatal results for both the mother and the child. Then he would preserve these strange creatures who had never really lived. So it’s not exactly death that we’re talking about. We’re talking about never having been born, in some profound sense. So he would make these weird, disturbing preservations, but at the same time he was a profoundly humanistic doctor.

LH: Yes. He detested exploitative shows of the preservations, and said it would be better to bury them than to exhibit them like that.

BLVR: So what did he intend with his preservations?

LH: He used them for education and for research. Separately, princes, aristocrats, and other rare visitors were able to see the specimens by appointment—rare glimpses of a world of wonder. These occasions were orchestrated judiciously. The jars, and sometimes the specimens, were partially covered with lace and ornamental fabrics that masked the more hideous or immodest aspects. Ruysch’s daughter, Rachel, from the age of six assisted him by sewing lace dresses decorated with beads, seashells, and pearls directly onto these creatures. There is even one in St. Petersburg that is decorated with a seahorse and a small coral!

BLVR: Let’s talk about how they got to St. Petersburg, and specifically about Peter the Great.

LH: Peter was quite a bit younger than Ruysch. He knew Russia was backward, Russia was inward, and he started looking out toward the rest of the world. He went to Holland and he became a laborer at a wharf because what he really, truly wanted was a navy.

BLVR: He was something like sixteen or seventeen years old at the time?

LH: Yes. And while he was in Holland, working as a laborer and acquiring twenty other crafts, by the way, he met Ruysch. In Russia, medicine was essentially nonexistent, and Ruysch ends up teaching Peter the Great dentistry. So the Russian czar Peter the Great becomes the first dentist in Russia—no joke! A collection of teeth he pulled from his servants and lovers is, to this day, on display in St. Petersburg! When Peter the Great sees Ruysch’s preservation of a boy child, Peter’s eyes fill with tears, according to the diary of Ruysch. He gets down on his knees and kisses the boy’s forehead and begs Ruysch to sell him his collection for Russia. He buys it for an astronomical price at the time—thirty thousand guilder—and sends it back with one of the first Russian sailors from Taganrog.

According to legend, the sailors drank the fluid from the jars. This is actually not true, although it sounds plausible for Russian sailors. Did not happen. The collection arrived absolutely intact. First it was placed in the summer palace of Peter the Great, then it was transferred to another place, then into the Kunstkamera, which became not only the first museum in Russia but also the first public library.

BLVR: Wasn’t there a twinned Siamese tree at that spot?

LH: That’s right. When Peter was looking for a place to build a house for Ruysch’s collection, he was going back and forth along the embankment, and he saw two pine trees growing into each other like passionate lovers intertwined—you couldn’t see where one began and the other one ended—and he said how wondrous nature is. According to legend he said, “This is where the Kunstkamera is going to be,” and that’s where the Kunstkamera is—

BLVR: The place you walked into.

LH: The place I walked into next to the Philological Faculty of Leningrad University.

II. THE PEBBLE IS A PERFECT CREATURE

II. THE PEBBLE IS A PERFECT CREATURE

BLVR: What exactly are we looking at when we look at these remarkable objects? There has been a lot of talk about death, but it’s not exactly death never to have been born. I mean, there is that great stoical line—“the best would be never to have been born”—and this is problematic, religiously speaking, because what exactly is the status of these creatures? Do they have souls and so forth? Could you talk a little bit about the objections that people had in Peter’s time to showing them?

LH: Well, first of all, they had huge objections to Peter himself, because Peter was essentially bringing enlightenment to Russia before there was enlightenment. And he was loathed, utterly loathed, by the Russian Orthodox Church. Monks would leave their monasteries in droves and roam the country without shelter and would proselytize that Peter the Great was the Antichrist. At the time, it was suicidal to go deep into Russia—it got very cold— but they would risk their lives to do this. For some of them, Ruysch’s collection was proof-positive evidence.

BLVR: Why?

LH: Because the creatures looked so demonic.

BLVR: The title of your book is Lost Souls. Were they thought to have souls?

LH: People didn’t quite know. According to one outspoken monk, their souls could not go anywhere. They could not go to heaven—how could they? They could not go to hell, because they had done nothing wrong, and yet limbo was assigned to the stillborn babies that were normal, and if they were to encounter these creatures, they would be too scared. So it was decided that since they couldn’t go anywhere, they would go nowhere. They were also not buried, and unburied bodies were suspected, as they are in many cultures, to be vampiric.

BLVR: When one says “lost souls,” does that mean that they are souls who have lost their way, or that we lost them, or what does the “lost” mean there, exactly?

LH: That the souls have no domain. They have no citizenship anywhere.

BLVR: Yet clearly, obviously, they have incredible purchase on us.

LH: They do.

BLVR: This is one of the things I wanted to get to about these images. I do not consider them morbid in the least—

LH: Me neither.

BLVR: The thing that’s incredible—you can’t say that about yourself; I said that; I’m praising you right now.

LH: But I’m talking about Ruysch.

BLVR: What I wanted to say is that what is overwhelming about your pictures is that there is a kind of tenderness without sentimentality. It is a lucid tenderness, and, in fact, a soulfulness just radiates off these images. I’ve been trying to think about that a little bit, and two Polish poems come to mind. One is the classic poem “ Pebble” by Zbigniew Herbert, for these are things that were never alive that we’re looking at. They might as well have been pebbles, in a sense. And as Herbert notes, “The pebble / is a perfect creature / equal to itself / mindful of its limits.” He describes it as “filled exactly / with a pebbly meaning,” and presently concludes by noting how “Pebbles cannot be tamed / to the end they will look at us / with a calm and very clear eye.”

LH: That’s very good.

BLVR: Meanwhile, though, Wislawa Szymborska, his contemporary, a great Nobel Prize-winning poet in her own right, has a poem called “Nothing’s a Gift,” in which she notes, indeed, how nothing’s a gift, “it’s all on loan.” Every heart, brain, organ, or limb will eventually have to be returned to the earth from which it came, and so for that matter will every feather, wing, tentacle, or branch. “Every tissue in us,” she says, “lies on the debit side” of this infinite inventory. “I can’t remember,” she concludes, “where, when, and why / I let someone open / this account in my name. / We call the protest against this state of affairs / the soul. // And it’s the only item / not included on the list.”

LH: Beautiful!

BLVR: These creatures are so eternally on the cusp of living, on the cusp of liveliness. I really want to push away the notion that this is about death. This is about immanence. This is about being on the cusp of living forever.

LH: That’s right. These fetuses seem to be oxymorons. Although dead, they appear very much alive in the work of Ruysch and his followers. Somehow, mortality and immortality, things that you can’t imagine being simultaneous, actually are, because these creatures are immortal forever. All their siblings and relatives are long dead and reduced to dust, and yet they’re still here. They have made it. As a photographer, I feel an extraordinary kinship with the archivists and the cabinet-makers. They captured the fetuses in what the painter Edvard Munch called “the frieze of life.” They preserved a moment that was meant to perish and sent it to us like a message in a bottle.

BLVR: Literally a message in a bottle.

LH: And we can go back and meet it halfway. If we have our eyes open and hearts strong enough, we can look at it and think about these things.

III. WOBBLING GHOSTS

BLVR: You work in your darkroom developing your own pictures, right?

LH: I develop my own negatives and I print my own prints.

BLVR: One of the things I wanted to talk to you about was precisely Ruysch in his darkroom and you in your darkroom. Ruysch is taking these stillborn creatures through a—it’s not formaldehyde—some concoction he is pouring. He is basically pouring this elixir of eternal life into the jars and working in these secret ways in this darkroom, perhaps by himself. Is the darkroom, for you, key?

LH: Yes. I arrived at an understanding of photography and light in the darkroom. I did not study in an art school. I studied linguistics and philosophy. I learned photography in a sort of medieval way, through an apprenticeship to two truly great master printers, an Italian printer from Milan named Ivan Dalla Tana, and Marc Valesella, a French printer who lives now in Los Angeles. I learned and tested all kinds of techniques for developing negatives, and I settled on actually one of the first techniques, called pyrogallol, or, as it is more commonly known, pyro. Pyro was first discovered in 1802 by Thomas Wedgwood, son of the famous maker of fine china, Josiah.

BLVR: Porcelain.

LH: Yes. They found that, for example, if you leave keys on leather and then if they’re exposed to the sun, you see the outline as an imprint.

BLVR: Don’t you just hate it when that happens? [Laughter]

LH: Thomas Wedgwood figured out how to secure the outlines of objects with pyrogallol crystals. Then, in 1841, almost forty years later, Henry Fox Talbot patents the technology, and in the 1880s it actually becomes a product, until easier but inferior processes are invented. Pyro taught me to understand the way light works, and also how to build a picture like a sculpture, as it were.

When you take a picture with your digital camera, you make a file—a series of zeros and ones. But with a negative, you are creating a three-dimensional thing. With pyro this is especially true, because it builds a stain. The negatives come out slightly heavier than at the beginning of the process. At the edges of the outlines, you see the clumping grain—pyro produces negatives with very strong and consistent edge effects—and they look like engravings, like plates for etchings. Pyro is very complicated and requires a great deal of patience. It is toxic, and the outcome is not very predictable. For all those reasons it is not used anymore, although it is by far superior to anything else invented since. But I should say I’m not interested in pyro out of a sentimental attachment to the past. It is simply the best existing technique.

BLVR: What must it be like to be there in the darkroom as the image is coming up, welling up out of the past—or where is it welling up out of, exactly?

LH: Do you know E. G. Robertson?

BLVR: The Phantasmagoria.

LH: Yes. In 1797, E. G. Robertson created a magic lantern theater whose specters and illusions amazed audiences. He had a magic lantern placed at an angle on rails behind a screen, and he projected angels, witches, ghosts, even a bloody nun. Unseen to the viewer, he rolled his lantern along a rail behind the screen so the distance between the lamp and the screen changed. The projections moved in ghostly ways: grew larger or shrank. The ghosts wobbled and wafted. When I saw the images from the cabinets appear for the first time in my trays, the experience was something like that—just spellbinding.

My darkroom—because I use volatile chemistry— has to be really, really dark. In fact, I become completely nocturnal, so nocturnal that when I drive out, I have to put a big yellow sticker on my driving wheel: turn the lights on. Because when I drive out at night, I don’t really need the lights, but other cars do, and they start honking because I drive like a ghost in my car at night.

BLVR: There is an incredible essay of Sartre’s, which isn’t all that easy to find, called “Faces.” It’s in a collection of essays called Essays in Phenomenology. Somebody should just take it and carve it into stone on a building, it’s so beautiful. It’s just a short essay where he is trying to figure out, what is it about faces? What are faces, at their essence?

He notes how, obviously, they’re flesh. But they’re not flesh the way a thigh is a thigh. They are “pierced with greedy holes.” He says: “Universal time is made up of instants set end to end; it is the time of the metronome, of the hourglass, or of fixed immobility. Now we know that a marble floats in a perpetual present; its future lies outside of itself…. Against this stagnant background, the time of living bodies stands out because it is oriented.” It is moving toward something.

“And so it is with faces. I am alone in a closed room, submerged in the present”—we’ll say a darkroom—“the future is invisible.” You’re by yourself, there is no future, you’re completely present in the present. “I imagine it”— the future—“vaguely beyond the armchairs, the table, the walls, all these sinister and indifferent objects which hide it from me. Then someone enters, bringing me his face; everything changes. In the midst of these stalactites hanging in the present, the face, alert and inquisitive, is always ahead of the look I direct upon it.” A mist of futurity surrounds the face—its future—just a little trail of mist—only enough to fill the hollows of my hands.

LH: They have so much human expression. It’s not an accident that the creatures’ hands are folded as if in pious prayer. The anatomists were compelled to set them up in tableaux form. They looked alive. They didn’t look dead at all. They looked like they were having a whisper, or a tender disagreement.

BLVR: I’m struck by the rhyme of that with that Nabokov line from Speak, Memory that you like to quote so much.

LH: It’s one of my favorite sentences in all of literature: “The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for.”

BLVR: Indeed. For what is so moving to me about these images? It feels so profoundly, philosophically confusing and confounding and vertiginous, the way we meet this gaze that was never there.

LH: That’s right. And that is a riddle and it remains to me a riddle, and it’s beautiful to me, that mystery.

IV. THE MICE ORCHESTRA

BLVR: A whole body of your work deals with bullfighters, toreadors. That’s a different aspect: gazing upon people gazing upon death, or people who look death in the face.

LH: The thing about death is you cannot photograph death, because you cannot photograph nothing. Death is nothing, and you can’t photograph nothing. There has to be something to photograph. But one thing that I always was afraid to do is sort of nice work. I don’t want to do nice work.

BLVR: Oh, you Russians!

LH: I know! I want to preserve the moments that capture me, and I cross my fingers that someone else might feel the same. With the bullfights, I had the same reaction as I had to Ruysch’s work. It wasn’t something that I liked, it wasn’t something that I loved, it wasn’t something that was pretty, but it had a sublime beauty about it, alongside all the awful other things that come to mind. Because it is complicated territory, it does not leave you easily, and that’s important. Of course, there was also something peculiarly Gogolian about—

BLVR: Gogol.

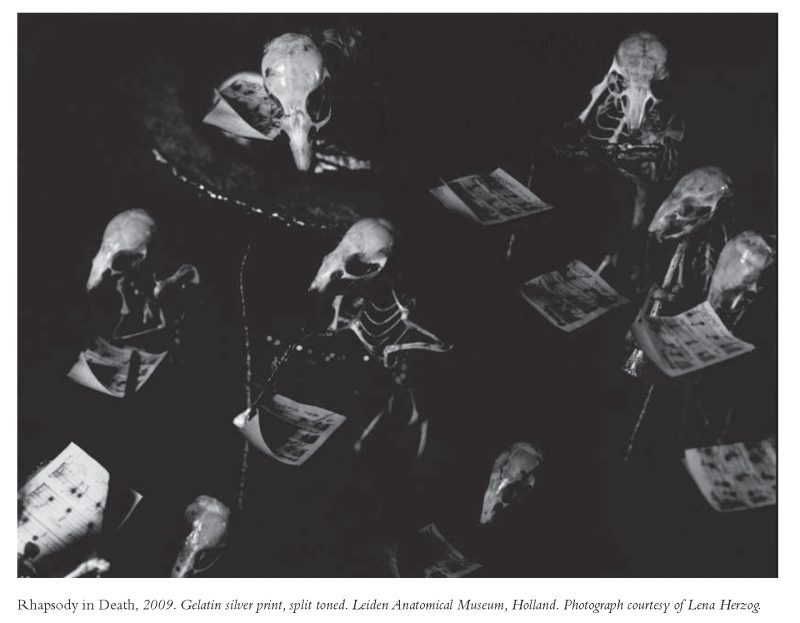

LH: The great Russian writer who founded the venerable institution called “the Russian novel.” The first book so considered by Russians and the critics was his Dead Souls. In it, there is the combination of tragedy and comedy. It sounds odd, but in a lot of the cabinets, comedy is also very present, especially in the mice orchestra of E. J. van der Mijle, which is sequestered in a catacomb, not on display, at the Leiden University Medical Center. When I asked why they hid it, they said, and here I quote, “The museum commission decided that it wouldn’t fit the storyline at the new permanent exhibition at the Leiden University Medical Center”!

That’s unfortunate. It’s actually a problem for a lot of cabinets, because they don’t fit into our ideas of how to exhibit bodies or skeletons, even if it’s mice. The story of van der Mijle is really quite extraordinary. He also fits exactly the profile of all the cabinet makers. They were all polymaths, highly sophisticated, a little cranky, and van der Mijle was particularly so. He was known at the time to be sort of a nineteenth-century hate-blogger.

BLVR: What?

LH: Like a blog. He would write hate poetry.

BLVR: “Hate-blogger.”

LH: Like a hate-blogger, yes.

BLVR: I thought that’s what you said.

LH: He would write hate poetry in Latin to all his presumed enemies, and he would write it out and then nail it to the door of the enemy, as Martin Luther did. For example, when he hated a particular building, he said, “This building has been made of rotten cheese and false weight.” Sometimes he would write in pentameter about things he really couldn’t stand. At the same time, he delivered over five thousand babies. A very great country doctor. Also, he had mice in his barn.

BLVR: What year are we in right now?

LH: The late nineteenth century. It took me two years to persuade the curators of the Leiden Medical Center to allow me to photograph it. It is a small display, it’s only this big, and it’s an orchestra! It’s an orchestra made of the skeletons of mice that van der Mijle found in his barn.

BLVR: It’s gorgeous. You cannot—you have ruined your life if you don’t go over to the International Center of Photography right now and see Lost Souls. But before we go, and as our way of sending you out with joy in your hearts, we give you the mice orchestra.