Instead of answering, Lucrecia Martel prefers to draw. She bends over a small black leather backpack that rests at the foot of her chair and fishes out a black ink pen. Then she traces a straight line on the brown kraft paper tablecloth.

I’ve just asked her about the relationship between foreground and background action in her films.

“This is how it works,” she says. “Look. In the systems I create, the screen is flat, but it is also a window through which you can perceive volume. That volume”—she points the pen forward into the air and moves it in circles—“exceeds the limits of the screen. It goes deeper; it goes beyond.”

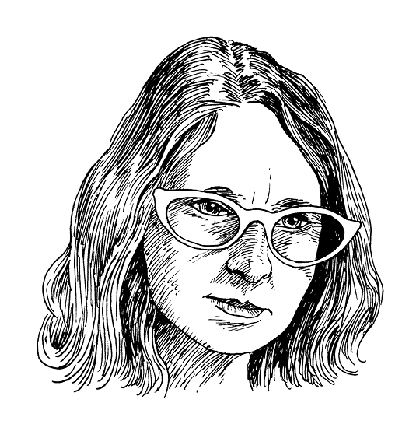

Lucrecia Martel rarely repeats herself. She hasn’t done it in any of the interviews she gave in her native Argentina to introduce Zama, perhaps her strangest film, nor will she do so during our conversation today.

It’s November 2017, and we are talking at Roman’s, one of restaurateur Andrew Tarlow’s places. Diners stand by the bar waiting for tables. Martel drinks a languid lime soda in bird sips. It’s nearing six in the afternoon. Brooklyn’s autumn is heavy, fragrant with dried leaves, withered. Martel arrived in New York two weeks ago in search of an international distributor for Zama. Before heading back to Buenos Aires, she will find one, and also learn that her film has been selected to compete for the Oscars representing Argentina. It’s an odd choice; Zama won’t even make it to the nominations. Martel is not, in fact, an industry director, but in the United States she has garnered a cult following of which, she says, she is rather unaware.

Since 2001, when she released her acclaimed debut, The Swamp (La ciénaga), Martel has been the star of the New Argentine Cinema (NAC), a thematic and stylistic renovation spearheaded by filmmakers Bruno Stagnaro, Adrián Caetano, Pablo Trapero, and Lisandro Alonso, and coalescing around a key producer, Lita Stantic. NAC leaves behind the main themes of Argentine filmmaking’s post-military coup (genocide, state terrorism, and censorship, all of which were a cinematic response to the last military dictatorship), and starts to delve with sharp minimalism into the destinies of the new democratic lower and middle classes. Zama is, in that light, both a break in continuity and a change of direction.

But Martel is in a class of her own, among the most innovative Latin American filmmakers of all time. Her aesthetic combines in strange proportions, the thrill, suspense, and visuals of the American zombie apocalypse flick with the discarnate social commentary of...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in