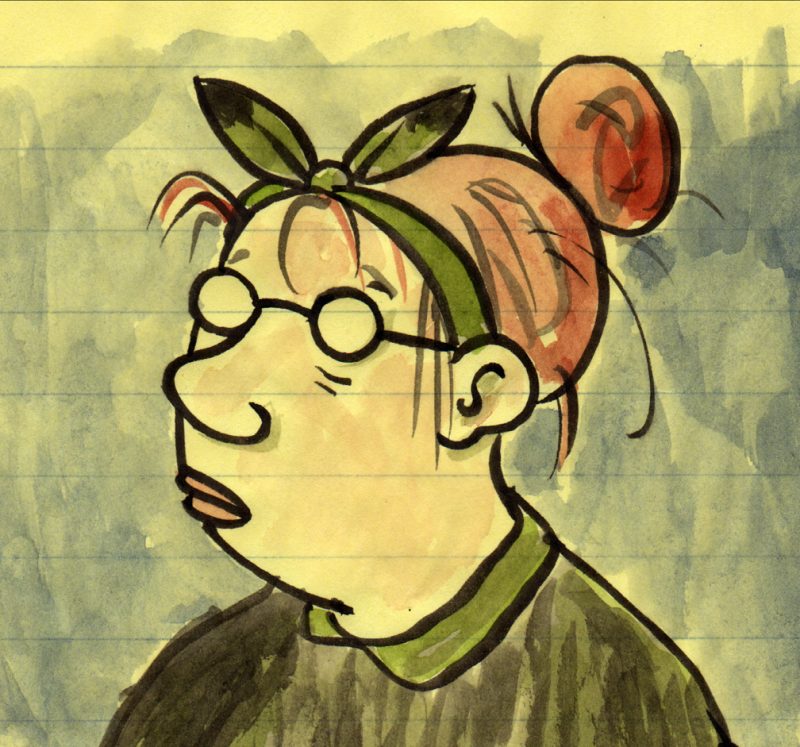

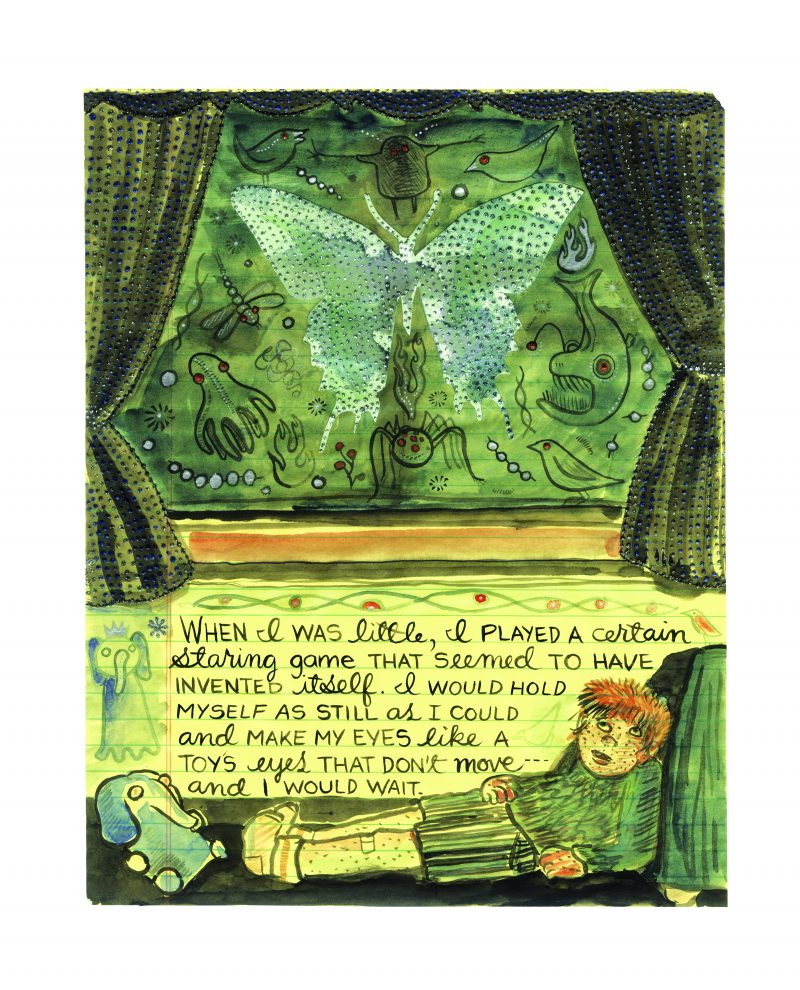

One of America’s seriously multitalented artists, Lynda Barry is the author of sixteen books. These include Naked Ladies! Naked Ladies! Naked Ladies!: Coloring Book (1984), which offers black line-art of a deck of cards’ worth of women, with a narrative about Playboy and boners scrolling through its fifty-four pages; comics collections such as Girls and Boys (1981), Down the Street (1988), Come Over, Come Over (1990), and It’s So Magic (1994); and two novels: The Good Times Are Killing Me (1988), a story of interracial friendship that became a successful off-Broadway play, and the gory, darkly hilarious Cruddy (1999) (which the New York Times called “a work of terrible beauty”). The Greatest of Marlys!—a “best of” comics volume—appeared in 2000, featuring Barry’s most beloved character, a smart, spotty, bespectacled child. This was followed by the genre- and form-bending One Hundred Demons (2002)—an experimental autobiography in gorgeous color, which loops through Barry’s life in comics frames and meditates on themes in thickly layered collages made from everyday materials such as stamps, paper bags, and pieces of old pajamas. Barry’s latest taxonomy-defying work, What It Is—based on a writing course she teaches about memory and images, “Writing the Unthinkable”—appeared this year courtesy of the comics publisher Drawn & Quarterly, which is set to reissue five out-of-print titles from her backlist. This year, her nationally syndicated comic strip Ernie Pook’s Comeek celebrates its thirtieth year of existence.

Barry is the editor of The Best American Comics 2008, and she is working on two projects: a third novel, and The Nearsighted Monkey, a collaboration with her prairie-restorationist husband, Kevin Kawula. The two live on a farm in Wisconsin. (“We’re almost off the grid. We’re like hard-core hippies. We heat with wood and cook with wood and bake our own bread and grow our own food.”) The titular character is, she explains, an alter ego of herself: “She comes over and it’s like she’s the kind of guest who comes a day early. When you come home from work she’s wearing your clothes. She has no hesitation in drinking all your booze, but at the same time you kind of like her.”

I took Lynda’s “Writing the Unthinkable” workshop in the summer of 2007. Almost a year later, in early June 2008, I interviewed her over two weekend days in New York City. For the first—the morning after we’d both attended the Post Bang: Comics Ten Minutes After the Big Bang! symposium at NYU, where Lynda was the headliner—we met at Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s RAW Books & Graphix office in SoHo. For the second, Lynda and I drank beer and ate eggs Benedict at 10 a.m. at M&G bar in the Village, where she humored me by graciously watching the French Open on television as a warm-up to talking.

—Hillary Chute

I. “THE ONLY BAD PART WAS I HAD TO BE NAKED IN ORDER TO EXPERIENCE THIS, BUT THAT WAS FINE.”

THE BELIEVER: When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

LYNDA BARRY: I liked drawing, but in my house it wasn’t anything that was of any value to anybody. And I liked reading and I loved stories, but I didn’t love reading and stories and drawing in that way in which you hear people talk about their past, you know? You get this feeling like there was this moment when they knew.

I always had an impression of myself that I just wasn’t quite doing it right. Even when I went into the library, I didn’t care what book I grabbed. I never feel like how a lot of writers do when they talk about their relationship with the book. It was just like classifieds ads were the same to me as anything in the library. And so when I got to college I tried really hard to be smart, smart, smart in that traditional way of being smart. And I remember I would be in these seminars and I saw people that had highlighters. You know, I didn’t know any of it, so I’d see that they read their books with highlighters, so then I’d read my book with a highlighter, and we’d sit down for a seminar and it would turn out that over and over again the one paragraph everyone had highlighted would be the one that was not highlighted [in my book]. But I was trying; I studied the history of science and the history of the Renaissance, and the way that things were at the Evergreen State College, the idea was that you studied one subject intensively.

And I was really broke and I was sitting in the lunchroom trying to figure out how I was going to stay in college, because I put myself through college, and one of the art teachers came in. I felt like I could already draw, so I shouldn’t spend money on taking drawing and art classes. And so he came in and he was all flipped out and I remember exactly: I was sitting there and I was drinking this cup of coffee and just, you know, drinking more coffee and he said, “You model, right?” And I went, “Yeah!” Because I had a friend who did lifedrawing modeling and I knew they got paid four bucks an hour, which was a lot of money for me then. I had never done it, but I had seen life-drawing classes. And so he says, “You model? ’Cause my model just flaked out on me and I got a class. Will you come and model?” and I’m like, “Sure!” I’m following him with my heart pounding: I’m about to go in this room. I’m gonna take off all my clothes.… And the nude modeling I had seen was in Playboy, right?

BLVR: Yeah…

LB: So I do it, just like, “Yes, I do this all the time!” I took off all my clothes and I climbed up on this table and he goes, “We’re gonna do short poses,” and I go, “OK,” and so he goes, “Change,” and I was doing all these Playboy poses, because I didn’t know how else [to pose] when you’re naked. And I remember him saying, “Could you make it a little less dramatic?” And so then I became this life-drawing model, and I really appreciated the income. It turns out I love holding poses. I can hold still for a really long time. Well, it’s that thing I had when I was a kid.

BLVR: To make yourself sort of doll-like.

LB: It turned out that I knew exactly how to do it, and I loved holding very still and being in a room where people were drawing and I could watch people drawing. It was heavenly to me. The only bad part was I had to be naked in order to experience this, but that was fine. I was cool with it. But when I was modeling for Marilyn Frasca’s class, I would notice that there was a whole other thing going on in the room. Marilyn would go to each person and just stand with them while they were drawing and then they would at some point look at her, and she’d go, “Good.” That’s all she’d say, and she’d let whatever was happening happen. And while I was sitting there, I started to get fascinated with this teacher, and then one day I was modeling and I just started crying because I realized I didn’t want to be on the table. I wanted to be in her class.

And that next year she was teaching a class called “Images,” and there were a lot of people who wanted to get into it and she let me be in it. And once I got into her class, that changed everything, because it’s the class [“Writing the Unthinkable”] that you took. It’s the class that What It Is is based on. That very idea that writing and painting and all of these things we call the arts are the same thing, that they come out of something that’s lively. I mean even, even if you think of Art Spiegelman’s—if you think of Maus, those characters there. You can ask those same questions. You can say, you know, are they alive? Are those characters… is that…? Are those characters alive? Well, they’re not alive in the way we are, but are they dead? Hell no.

Check this out. We did have critiques, but the critiques were that you’d come and they’d put the work on the wall. We just had to sit and look at it.

BLVR: And not say anything?

LB: Didn’t say anything, and so what you did was you learned to look. And so this idea that the work happens anyway was this revelation. I studied with her for that one year in “Images,” and then the next year I had an individual contract with Marilyn, and just studied with her. I did start making comic strips mostly to make my friend Connie laugh, but I knew very much about R. Crumb. I was crazy about R. Crumb when I was in junior high school. I was in seventh grade when I found my first Zap, but I think I had a completely different experience than a lot of guys did, because the drawings of the sex stuff with the ladies really scared the hell out of me. I copied and copied and copied and copied and copied and then I would try to find those collections, but if S. Clay Wilson or those guys were in it, they would totally freak me out, because I was looking for, like, the kids’ version, you know?

When I saw Zap I gotthat upsetness, that scrambled feeling, but Crumb had this thing. It was a comic strip called Meatball, and it was just one of his silly comic strips, but it would have little details. You know, there was this regular story going on, but in the background I remember he had this store and there was stuff for sale and there was a little tiny sign and it said, men from mars 25 cents or something. I remember looking at it, and I had always liked comics and I had always copied them, and I realized you could draw anything. What R. Crumb gave me was this feeling that you could draw anything. But it was really hard-core because the sex stuff was very frightening. When I look at Crumb… Well, let’s just turn to Cruddy, my second novel.Cruddy has murder galore. It’s, like, you know, it’s murder fiesta, and lots of knives and killing.

BLVR: It’s great.

LB: So does that mean that I’m a person who thinks about murder? Well, yes, as a matter of fact, I do think about murder constantly. Actually, when I’m talking to people who are driving me crazy, I often imagine they have an ax in their forehead while they’re talking to me. I know that that’s my personal relationship with murder and knives and blood. It doesn’t mean that I need to go do that.

II. “I HAD THIS SERIES THAT WAS BASICALLY WOMEN TALKING TO MEN IN THE BAR, BUT THE MEN WERE GIANT CACTUSES, AND THE WOMEN WERE TRYING TO DECIDE IF THEY SHOULD SLEEP WITH THEM OR NOT.”

BLVR: Where were your first comics printed?

LB: I had, I guess you could say, comic strips printed in my little high-school paper. I did a lot of graphics for stuff, but it was in college, when I had two friends…. Matt Groening was our editor at the Evergreen State College, and then I had a good friend named John Keister who was the editor at the University of Washington paper in the summer, and he was a pretty far-out editor. It’s funny: Matt and John were my two best male friends. They had the same birthday. Neither of them believed in astrology.

So they were both in charge of newspapers at the same time, and I would just send crazy little comics that didn’t make any sense to both of them. I would just drop them off in the mailbox to Matt. Matt fascinated me. Because he seemed so straight, but really he just loved to do anything that would piss off whatever the majority was, and at that time it happened to be hippies. If you look at his work, that’s what his work still is about. I mean, even with however The Simpsons giant fungus has morphed, you know? Even with all these writers working on it, it’s still about challenging the majority, and people in power. Matt’s always done that.

I love to just make him crazy. We’ve always had this kind of antagonistic relationship. We had this period where we were interviewed about each other. It was before The Simpsons and we were both doing these cartoons. We would tell big lies about each other, like I always loved to say that Matt was really into Joan Baez, was heavily into folk music, and he lived in a yurt at Evergreen, and I would just talk about how he was really into organic food, and, you know, total bullshit. And if you look at his calendars, when he does a calendar, he always puts my birthday, but he always puts it as though I was born in ’65. I was born in ’56, right? So we still do that with each other. But he was really important. He printed my first stuff, and my friend John did, too, but it wasn’t just that. Matt also was a cartoonist, and my friendship with him, I think, had everything to do with—along with Marilyn—why I kept drawing. One of the things about Matt is Matt really supports people who make comics. He’s behind them.

BLVR: So then what happened after he was printing your stuff, and John Keister was printing your stuff, how did it turn into a career?

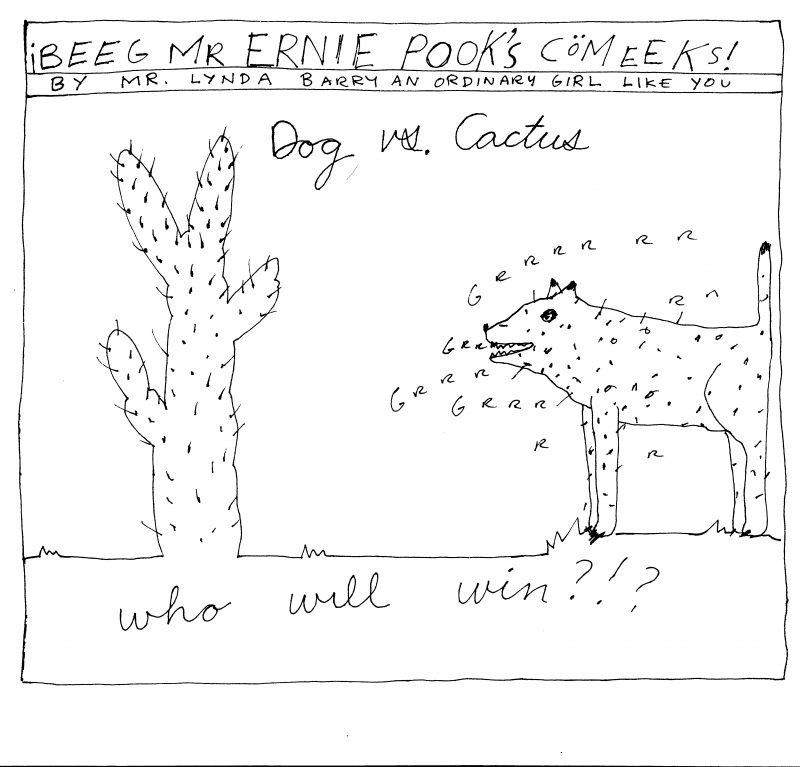

LB: So then I had some comics, and I had started this little series. I think they were called Spinal Comics, and I was going through a bad breakup and so I had this series that was basically women talking to men in the bar, but the men were giant cactuses, and the women were trying to decide if they should sleep with them or not. It was just the same joke, over and over again….

BLVR: But it’s a good one!

LB: They would be, like, saguaro cactuses with a bunch of cigarettes and beers and they’d be talking to them and saying all these sweet things to them and the women would be, “You know, maybe this could work. Maybe I could sleep with this guy.”

Anyhow, after I graduated from college and I moved back home to Seattle, the alternative papers had just started up, and so there was one called the Seattle Sun. And I think this is the true story of how people get published. I decided I was going to go in and submit my work to see if they would print it, and so I went, and like a lot of alternative places, it was in an old, gnarly house, and there were people working for no money there, and there was some woman who was in charge. She didn’t happen to be there when I dropped off my work, so I just dropped it off, and I live, like, two blocks away, and I put down the phone number. I got home. The phone’s ringing, and it’s her: “I’d like you to come in and talk to me about these comics,” and I said, “OK!” But there was something—it was weird because there was something about the way she said it that didn’t sound like she was really happy about them. So I go in and I come upstairs and she read me the riot act. She said they were the most racist comics she had ever read, and I was looking at her like, “Racist?” And she thought I was making fun of Mexicans.

BLVR: Because of the cactuses?

BLVR: Because of the cactuses?

LB: Exactly. I mean, you know, that’s how I was, with giant question marks over my head: “What?” Something about Mexicans and women, and Mexicans and white women, and, I mean, she really was crazy. The comics had nothing to do with Mexicans, or white women, so as I was going down the stairs I hear these feet behind me and there was this dude, and he ran the back page and he hated her, and he said, “What was she just yelling at you about?” and I said, “She hates my comics,” and he took me and he said, “I’ll print them,” and he printed them just to make her crazy. He didn’t even read them.

BLVR: This is so funny.

LB: This is how it really happens. So that newspaper was part of the Newspaper Association of America, which was all these alternative papers who decided, “Hey, there’s a bunch of us, let’s—” I’m sure they all got together so that they would have a reason to have a convention and have a party, you know? And so they started sending their papers, one to the other.

And at this same time Matt had moved down to Los Angeles, and he was working at a copy shop. That’s how he started making his Life in Hell comics. He could just make copies, and then he would send us copies of his stuff, but it wasn’t ever intended to sell or anything. And he got a job at the L.A. Reader, and he had to write and he was a good writer, and he wrote some article about… What was it called? “Neat” or “Dumb.” I can’t remember, but it was all about how lame stuff is actually cool. It was a revolutionary article, and he mentioned me in it, but like I was someone….

BLVR: As something lame that was actually cool?

LB: Yeah, but also he acted like I was a cartoonist of some kind of standing, which was just bullshit, but he was, and I was his friend. And then a guy named Robert Roth, who’s a wonderful guy who ran the Chicago Reader, saw it and then called me, and they paid eighty dollars a month. They still pay eighty dollars a month, but at that time my apartment was ninety-nine dollars a month, and so when I got in that paper for eighty dollars a month, I was selfsufficient. I could quit my job as a popcorn girl at the movie theater, and I could just concentrate on my work.

BLVR: This is in Seattle?

LB: In Seattle. Yeah, I lived above a key shop; it was ninety-nine dollars a month. At the same time, whenever I was in a paper, I started pitching Matt’s work, so as soon as they’d have me, I’d say, “There’s this other cartoonist,” and I’d send them Life in Hell, which was fantastic, I still love it. Whenever Matt or I got into a paper we would pitch the other person, and that’s how we did it.

And then Matt knew [“King of Punk Art” painter, cartoonist, and designer] Gary Panter. So when I would come down to see Matt in L.A., I would go visit with Gary, and Gary was beyond ahead of the pack. I mean, you didn’t even know that you were in a race or on a racetrack or that you were a horse.

And so through those guys, that’s how I ended up doing stuff. Not so much that I would have stopped, but between Matt’s relationship with Gary and Gary’s far-outness… Gary would have all these ideas and when I’d see him I’d see all these ideas, but also he’d give them to Matt, and then Matt would always report back on what Gary was doing, so between those two guys, Gary kind of through Matt, and Matt, I had a lot of support for what I was doing.

III. “I WOULD MUCH RATHER BE IN THE YOUNG ADULT SECTION THAN THE, YOU KNOW, ‘GRAPHIC NOVELS’ SECTION.”

BLVR: Tell me about when your first book got published. So you started being in papers, and then?

LB: Well, I actually had this book before the Girls and Boys book, but I published it myself.

BLVR: Wow, you have sixteen titles!

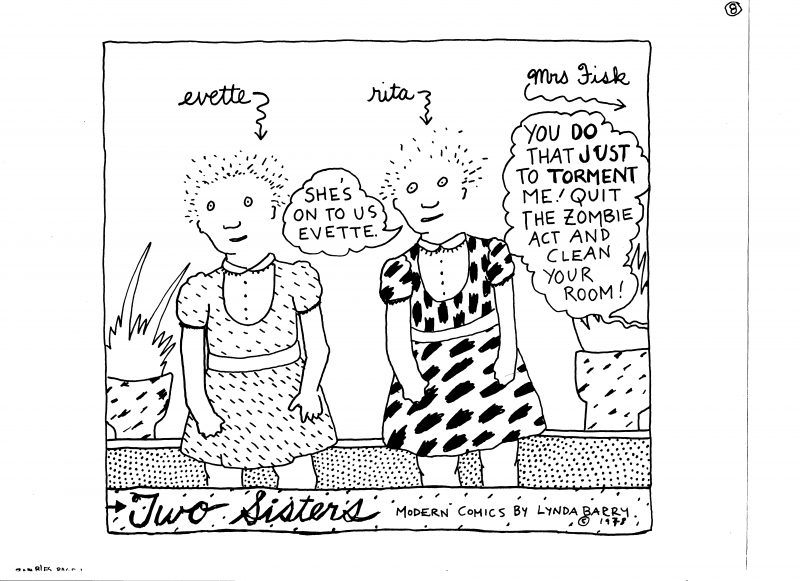

LB: If it counts. It was one that I did myself, and I just did it in Xeroxes. I had this series called Two Sisters, and it was twin girls named Rita and Evette, and people loved the hell out of that strip.

This was way, way, way back, and Rita and Evette were really popular and they were funny and copy shops had just come out, so I did a thing where I just copied the whole collection. I put it in a manila envelope and I hand-decorated the top, and I sold them for ten dollars. You know, so you just get a manila envelope and you pull it out and there’d be all the comic strips.

BLVR: And so it just sold by word of mouth?

LB: Yeah, or I’d actually write it in my comic strip. I’d put it on the side. If you’d like to buy something, call me on the phone. Then I’d take orders, and I’d go to the copy shop, and they’d copy them, and then I’d put them in and make the whole thing. But then after a while I couldn’t draw Rita and Evette anymore. Partly it was because people really liked them and then the strip kind of just ended because sometimes they do.

BLVR: What was the deal with them?

LB: They were twins, and their mom didn’t get them. They were odd kids, who the world kind of didn’t understand. When that ended, I started doing the first strips that you see in Girls and Boys. That very first one, if you see it, I think it’s the kids who are left at home, and a kid’s jumping on the couch and saying, you know, “When mom comes home you’re going to get in trouble,” and the other kid says, “Mom’s never coming home. She’s going to marry a bum.” So that was the first stuff that I did and the drawing was really kind of gnarly, too. It was really rough, compared to Rita and Evette, which is very sort of sweet. It’s not sweet sweet drawing, but it’s sweeter.

BLVR: It’s rounder?

LB: It’s rounder. It’s more really light lines. It’s more, you know, like there are really decorative parts, but then Girls and Boys was more… at the time, I started being called a punk cartoonist, you know? People called it punk art. It went: underground, then funk, then punk, then new wave, then alternative, and then, then, then… art. I guess “graphic novels,” graphic something, and then “art comics,” people call them, art comics. So I started doing these comics that had trouble in them, and people were very upset and I wasn’t in many papers at that time. People were very upset, because there weren’t many comic strips that had a lot of trouble, that weren’t funny, you know? The setup for a comic strip is four panels and that last thing should be a punch line, so when people didn’t get that punch line they became very upset and they would write furious letters to the editor about how there’s nothing funny about child abuse, and it’s like the strip wasn’t funny, it was sad. You know how my strips can be really sad?

BLVR: Yeah.

LB: And so there was this big trouble and at the same time I started making little comic versions. Now, you know, people make little minicomics all the time. I would take my comics after I printed them or after

they were reduced for the newspaper, and then I’d Xerox them from the newspaper, and I would make these little tiny comics and I sent them in to Printed Matter. It was a place where they sold artist-made books. It’s pretty famous in New York. It was the first zine printer. I sent them some comics, and it was right when I was getting the worst—people just hated what I was doing—

BLVR: Because of…

LB: The darkness. Whoever it was at Printed Matter wrote me back this note saying, “I really like what you’re doing.” You know, “We’ll buy.” I was selling for fifty cents each, and so I think they bought them for twenty-five cents, you know, and “We’ll buy, like, a hundred of them,” or something. And that little letter from whoever it was that wrote completely changed everything for me, because I thought comics were a way that you could write about really sad things, and write about long stories, but there wasn’t anybody doing it. You know what I mean? So whoever it was at Printed Matter—I don’t think I still have the letter; I may—changed everything for me, because they got it, and I thought, OK, well, somebody else is getting this.

BLVR: What year was that?

LB: It would have been the very late ’70s. Because if Girls and Boys was published in ’81, it probably would have been ’79, or 1980. And then the work in the newspapers, somehow people started to actually start to like it, once they understood that I wasn’t making fun of the situation, but that a comic strip could contain something sad, like a song. And I realized I could discuss anything in the comics.

BLVR: I was surprised that some of your early books are in a YA section or got a YA label. I think, OK, so what happens in this scene? OK, someone’s getting raped at this party, or whatever, and that always puzzled me.

LB: Yeah, but it’s very nice for me, because I feel like I could have found it that way. It’s also on the list for reluctant readers. OneHundred Demons is heavy. I mean, One Hundred Demons has some crazy, like…

BLVR: All of your work is heavy.

LB: So people say when they buy it, “This is for my son.” I always say, “How old?” “He’s seven, he loves comics.” “Well, just to let you know, there’s incest and suicide, and drug-taking. There’s, like, everything’s in there.” “Oh, he’s very mature for his age.” “All right.” Because kids, they do what I did when I looked at the S. Clay Wilson, which is usually, you just make it disappear. Or, if you have a reason to go to it, you look at it for as much as you can stand and then you look away.

But I would much rather be in the Young Adult section than in the, you know, “graphic novels” section. In a minute. If somebody gave me a choice I would so much rather be in a place where people don’t feel this pressure….

BLVR: So after you appeared at Printed Matter, you started publishing books.

LB: I did, and a bunch of other people did, too. I feel like Matt Groening’s Life in Hell stuff is totally disregarded. We were publishing books at the same time, but his stuff was hugely popular. We’d do book signings together, and he’d have a line around the block, and I would be sitting next to him and somebody would come up and say to me, “Where’s the militaria section?”

BLVR: Maybe I’m thin-skinned, but that sounds so crushing to me.

LB: It wasn’t at all, because Matt’s stuff and my stuff was really different, and if you’re gonna have a book that’s very clever and really funny and talking about people’s difficult situation at work, or you’re going to have a book that’s about horrible things that happen in childhood, there’s gonna be one that has a long line, and another one that has a shorter line. You know, it’s like he was selling really full dinners and I was selling condiments. It didn’t crush me at all. Not even a little bit.

BLVR: How did you get into this thing that you do that I think that nobody else does in the same way, which is this writing with casts of characters that include a lot of kids?

LB: It surely wasn’t through the thinking process. They just sort of appeared. But I don’t know how I came up with those characters, especially because it’s so unlike the way I grew up. You know, with no sisters, for example. I don’t know how characters come. In fact, it’s one of those questions that’s in What It Is because what I liked about What It Is is that I could ask questions that I didn’t know the answers to.

BLVR: Yes, the book has a questioning mode.

LB: Where do characters come from? I have no idea. I think they come from messing around. One of the most amazing things that I ever saw was two guys who were, like, street-theater dudes, who would do scenes from Shakespeare using garbage that was just laying on the street. “Hey, we’re gonna make this… It’s the Globe Theatre,” and they would really, literally pick up a cigarette butt, and a bottle cap, and then move them, and talk, do the Shakespeare, and you would watch them, like they really were Romeo and Juliet. There’s something about human beings where they make characters really, really easy. When I was a kid I was always disturbed by seeing shoes, like these tennis shoes here I’m wearing, without a foot in them, because I could see the mouth screaming. And part of my reason that I had trouble with math was that 3 always looked like it was screaming, and 5 looked like it was screaming. 3 could not be facing 5. 53—that looks like fighting to me. It terrifies me. 35’s fine, because then the 5 and the 3 can’t see each other. But so I had all those things from when I was kid— I guess it’s animating stuff. Things become animated or I feel like I can look at anything and kind of know where I put the eyes on it.

IV. “WEAR THESE AND YOU WILL TEAR THE PARTY UP!”

BLVR: I think one of the things that’s so striking about your work is the way the characters talk.

LB: I am really interested in language, but not the conscious part. The thing to remember if you think about my work is that I never pencil, and I never know what the next line’s gonna be, and so my whole thing is I draw until I actually hear it in my head.

BLVR: It doesn’t feel written in the sense of “someone is trying to write like this.” It feels like a real spoken thing.

LB: For some reason I feel compelled to repeat things that I hear people say. I remember walking through a clothing store and this man was shopping with his girlfriend or some woman, and he was like, “Dolores! Dolores!” and he held these pants, and he held them up, and he goes, “Wear these and you will tear the party up!” And I would always have to say, “Wear these and you will tear the party up!” ’Cause it’s like there’s a singing to it.

BLVR: There’s a heard inflection in your writing, which I think is a really amazing thing to be able to convey.

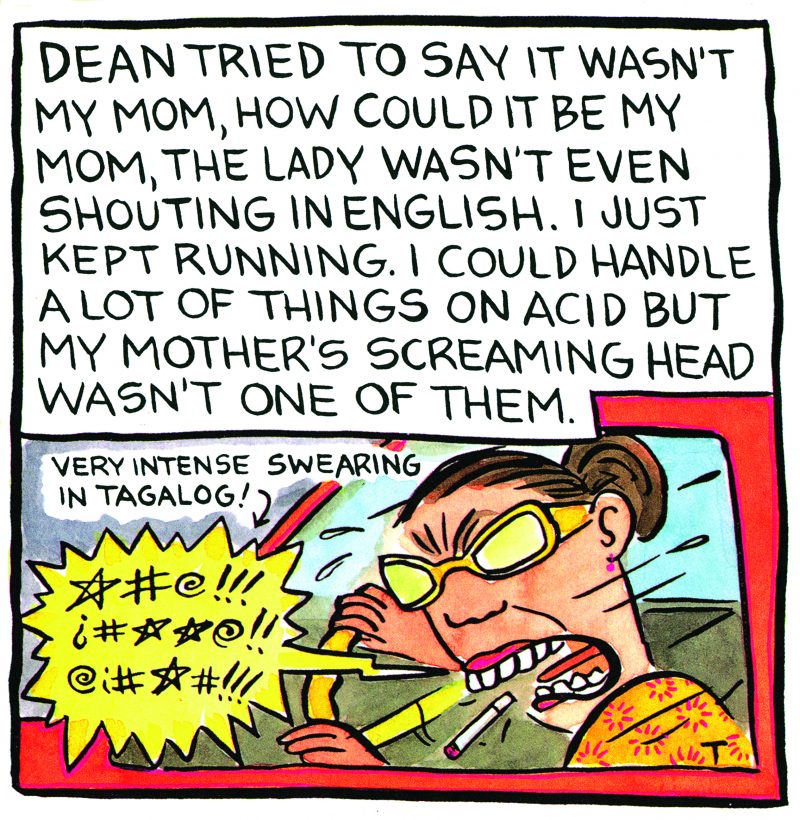

LB: And then again if I want to think about it: what could it be? And it’s just guessing: I grew up in a bilingual family, but where the language that the adults spoke was never taught to the children. All my cousins and I, we know certain words in Tagalog and we understand certain things, but they didn’t teach it to us.

BLVR: You just picked it up.

LB: Yeah, but I don’t speak Tagalog and I don’t understand all of it. It’s sort of like this: “[mumbling] hairbrush [mumbling] go to the store [mumbling].” That’s what it sounds like to me, you know. So I think I might have had an interest in language. I know that I went from being in Richland Center, Wisconsin, where my mom was the odd person with a heavy Filipino accent, and we left when I was four and then we moved to a house in Seattle that had… I don’t know. There was a varying number of families, but it was an enormous number of families, like anywhere from four to eight families living in one house, ’cause they were all coming over from the Philippines, and then it went to my dad was the only one who was speaking English. So I went from a thing where everybody was speaking [with a Wisconsin accent] “not just English but, you know, Wisconsin,” all the way to Seattle, where my dad was the only white guy, and then me and my brother who was just born, and everybody was speaking Tagalog. When that house fell apart and everybody had to scramble to find a place, we moved to a black neighborhood, which has its own accent thing going, and then it was also black and it was Asian. It was Chinese and Japanese and I…

BLVR: But not very Filipino?

LB: There were lots of Filipinos, too. I think I heard a big range of how language was spoken when I was a kid, but is that the reason? I don’t know for sure, but I know that I am compelled to write down what people say and also repeat it over and over in my head.

V. “IM THE OPPOSITE OF A SNOB WHEN IT COMES TO READING SOMETHING.”

BLVR: I want to ask you a few of the questions that you ask in What It Is. What is the past and where is it located?

LB: In our heads we have it that we’re rolling into the future. There’s this feeling that there’s a chronological order to things because there’s an order to the years, and there is an order to our cell division from the time we’re a little embryo until we’re dust again. But I think the past has no order whatsoever.

BLVR: How are images a part of that?

LB: I think that that’s what you call the units, or the things that move through time. We think of time, or the past, as moving from one point to another. If you think of these images, they can move every which way, and you don’t know when they’re coming to you.

BLVR: So one of the other questions is about what’s the difference between memory and imagination. What do you think?

LB: I think that they’re absolutely intertwined. I don’t know if there’s necessarily a difference, but I don’t think they can exist one without the other, absolutely not. Like that question, can you remember something you can’t imagine? I like those questions that when I think about them they make my brain kind of stop. You know, is a dream autobiography.… Is it autobiography or fiction?

BLVR: I love that question.

LB: Yeah, if you’re the kind of person who gets interested in that stuff. The thing that I have a hard time understanding is for a lot of people, it’s not interesting at all. Like not even kind of. It’s sort of like how video poker isn’t interesting to me, not even a little.

BLVR: So, one of the other questions is, can you make memory stronger?

LB: Yeah, absolutely. I do think memory’s something you can absolutely make stronger and it’s just this thing of noticing what you notice, just by doing the easiest diary in the world. We did it in the class, where you just spend three minutes a day writing down the ten snapshots [from your day].

But what’s wild is the back of your mind will jump ahead of you. You think you’re going to write about: I was in a car wreck, or these big things happened. Soand-so finally called me. But it’ll be: potato chip bag on floor under bed. You start to realize there’s the part of the day that your thoughts think is important, and there’s this other part. Then you give it a chance to come forward, and you start to notice what you notice. When I’m doing that, I start to notice what I notice while I’m noticing it, and it makes the experience of being around richer. A lot richer. When you realize what you really notice is something super specific, and when you start to see that—when you start to realize there’s a part of you that is really active—you can either ride along with it, up on top of the bus, or you can sit in the back, with your head down, looking at your cell phone.

BLVR: What was it like editing the Best American Comics 2008 volume?

LB: I’m the opposite of a snob when it comes to reading something. I’ll read anything that has handwriting, and it’s really hard for me to be bored or unhappy when I’m reading comics. I even love stuff that, you know, when you’re reading it, you might think, This isn’t really working, or this isn’t really exciting. I never think of that. I think, Drawing, writing, handwriting, drawing. I’ve done this new thing for when I pick a novel now. It used to be that I’d really sweat over what book I was going to read next. Now I have a good friend whose mom died. So they were cleaning out her mom’s house, and she gave me this gigantic box of books. So now what I do when it’s time for me to read is I just close my eyes and whatever book I pick, that’s the book I’m gonna read, and I always end up reading the books that at first I’m going, “Oh no.” Did I already tell you this story?

BLVR: No.

LB: The last one I just read. It’s called Breath and Shadows, and it had kind of a floral cover, and right away it had a dwarf in it, and, like, a talking cat, and I’m like, “Oh no, no, no,” but I had made the promise. It turned out to be incredible, just such a good book. I was so sad it was over. So now I realized you just don’t have to be picky, because you’re bringing half of the experience, no matter what, you know?