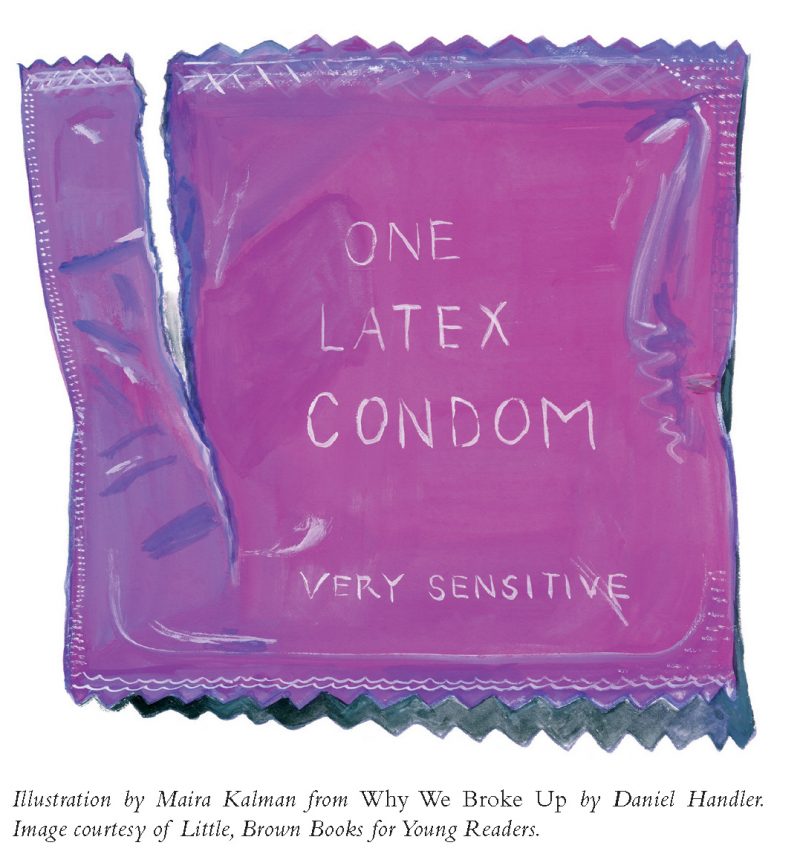

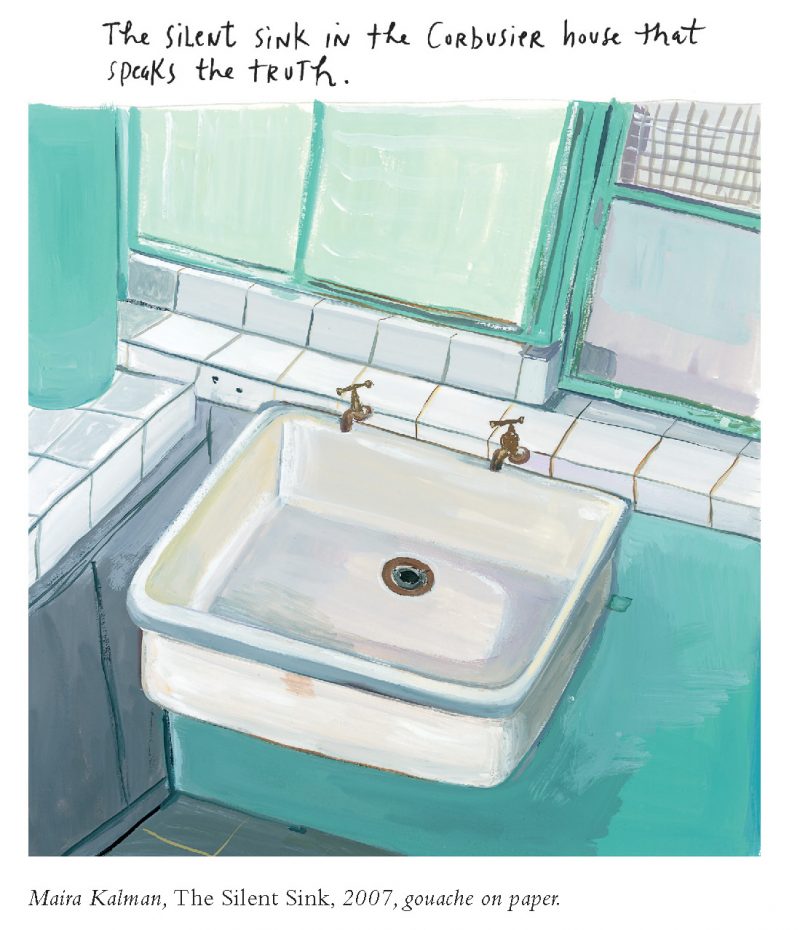

Sixty-two-year-old artist, illustrator, writer, and designer Maira Kalman has had a remarkably productive decade. A retrospective of her art has been traveling the country, and she recently published her second graphic memoir, And the Pursuit of Happiness, a whimsical and personal look at the world of the founding fathers, which first appeared as a visual column in the Opinion Pages of the New York Times. In 2007, she published her first graphic memoir, The Principles of Uncertainty (also originally a column in the Times), and has illustrated Strunk and White’s classic The Elements of Style.You may also be familiar with the famous “New Yorkistan” cover for the New Yorker she created in collaboration with the artist Rick Meyerowitz, her numerous children’s books, and her work with Lemony Snicket, David Byrne, and Michael Pollan.

But before her current success, the Israeli-born Kalman had another life behind the scenes, as the influential graphic designer Tibor Kalman’s wife and collaborator. Maira is the M in Tibor’s seminal design firm, M&Co, and their marriage was a famously creative one, resulting in enduring and imaginative designs like a crumpled-sheet-of-paper paperweight, a wall clock empty of all numbers save the number five, and a black umbrella with blue sky and clouds on the underside. Their collaboration ended when Tibor died, in 1999, from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Since then, Maira has established the strength of her voice on its own—a voice that dances between wisdom and innocence, lightness and tragedy, the personal and the external, and which draws inspiration across genres, from Saul Steinberg to Matisse to Nabokov to Bach.

With an unassuming attitude and a general affability, Kalman answered the questions I posed at her kitchen table in Manhattan, over glasses of water, on one of the hottest days of the year.

—Nell Boeschenstein

I. THE SITUATIONS AND THE STORIES

THE BELIEVER: You say you were a writer and poet before you thought of yourself as an illustrator. How did you come to combine elements of both? Did you feel as if the single genre was insufficient and limiting?

MAIRA KALMAN: I definitely thought that doing only one or the other was not sufficient to tell a story, and of course there were some precedents for people who write and draw together, from the Dadaists, and, before that, from books and illuminated manuscripts. For me, it was about editing the work down to the most pithy content and the most descriptive art—the most narrative art and the most visual writing—so I was able to tell my story in both those ways. And maybe part of me thought I wasn’t good enough at either to do only one. But I did know that I needed to do both.

BLVR: When you say “my story,” what story do you mean?

MK: The madness and amazingness of everything that’s going on around me. I just needed to express what I’d seen and show it to you, attempting to convey the humor and the pathos in it.

BLVR: You’ve said your dream is to walk around the world with a small backpack, but I worry that if that came to fruition, you would either miss your stuff or you’d collect so much stuff along the way that you would eventually be unable to carry it all.

MK: Well, I would send it. That’s the practical response. I would just send the stuff that I would collect along the way. It’s such a fanciful, unrealistic idea. How do you really do this? I don’t want to go climb the mountains and swim across the oceans, but I think there’s a way of representing that idea, which is just to walk a lot in general, and that represents walking around the world for me.

BLVR: In your work, there’s a tension between ideas of collecting objects and a true appreciation for objects themselves, which is in conversation with certain notions of simplicity.

MK: Well, everybody likes to have some stuff around, and I think that if I were trying to simplify I would take pictures—which I already do—I would take pictures of things that I fell in love with. But then again, I don’t know what would happen if I decided to walk around the world, and that would be the delightful part of it—that I could not pre-figure-out what objects I would want, or what things I would miss, or what I would take with me.

BLVR: Your work has been described as “children’s books for adults.” I was wondering if you feel this description is apt, and, if so, how you interpret it, and what you think it means or says about your work.

MK: If an adult children’s book means that there are paintings and writing and there are digressions and eccentricities, then that’s what I do, but I’m not quite sure what that means. It probably means that it’s naive and whimsical and there are flights of fancy, and all those things are true.

BLVR: Your work is imbued with the tension between idealism and naïveté, and the hard realities that emerge once the surface of that idealism or naïveté is scratched. In your work, the scratching of that surface is more implied than done on the page, and is experienced emotionally rather than intellectually. Yet that tension is also at the heart of the American mythology. I was wondering if this tension played a role in attracting you to the And the Pursuit of Happiness project.

MK: Well, just to talk about the project, I was interested in it because it seemed like an optimistic time in political history. I have no interest in politics, so therefore I thought, Why not do something I know absolutely nothing about? But the nature of the human condition is that there is this napoleon of happiness and confusion and tragedy and optimism and sadness and loss and delight. That’s inescapable for everybody, so it can’t be that we do work unaware of those layers. The day is fraught, from morning to night. So many different emotions race through you. I can’t imagine a situation without that, so it’s not just America, it’s everybody on earth, every story you read—everything incorporates some aspect of tragedy, whether it’s acknowledged or implied.

BLVR: Do you think of these American stories as universal fairy tales?

MK: I don’t think of them as fairy tales, but they are definitely universal. There’s always this struggle of surviving and flourishing, the bad luck and good luck. It’s just something that you’re constantly negotiating, and it’s always in flux. Then, if you want to add another level of loving people and then worrying about what will happen, what may be happening, what will happen, what disasters will befall you, that’s a full-time job, and some people are predisposed to worry about which disaster will fall when.

BLVR: The optimism inspired by the 2008 election and Obama’s inauguration has since been a bit tempered. Do you feel as engaged by that material now? Do you think you could write a similar book now as another election approaches?

MK: No, that was very specific. That was a fairy-tale moment for many people—this person becoming president, this man who was so singular and sweeping such energy into the air, and it’s no longer there for many different reasons. But in the end, it’s the same moral, which is that it’s just about time, and it’s just about hard work, and there aren’t these phenomenal moments where everything changes.

BLVR: You’re an Israeli immigrant but a naturalized American citizen. Which of these stories about America feel native to you and which remain a bit foreign?

MK: Oh, all of it is foreign. Completely, 100 percent foreign. Completely foreign to me. But again, it’s foreign to my personality to talk about politics. To talk about anything realistic is completely out of my vocabulary.

BLVR: But these stories aren’t about politics, they’re about people.

MK: Yes, but even using the fact that people are doing specific things—people run for office and they do a job— that’s incomprehensible to me. Somebody becomes a Supreme Court justice, which means they’ve been a lawyer, which means they’ve gone to law school. I mean, how does anybody do that? And of course it’s absurd: many people do it. But for me, the actual fact that somebody does that in the course of a life and it’s a real, true thing— that’s extraordinary to me. Wandering around in a park, not knowing where you’re going, that I can understand.

II. THE TABLE WITH THE CAKE ON IT

BLVR: You have an attraction to old stuff. What do you think of this idea of “vintage”?

MK: Well, it’s funny. Lately, I’ve been thinking about friends of my parents’. I guess it also depends on how you define old—how old a person is and what they think old is. There’s something about the things that you see, or the things that connect with the time when your life perhaps seemed like the truest form of your life. From my point of view, that’s my childhood, or those early years surrounded by my family, and by the architecture of the apartment in Tel Aviv, and by my mother’s dress, or by—I don’t know what— the table with the cake on it. That resonates so strongly for me. So it’s my personal history that draws me to the past. Then I get interested in other people’s pasts. I mean, where do you come from, what are the things that your family used? Those things have such meaning and importance to people. Of course, I like the things of now and things of the future, and modernism and not feeling retro, but history has a pull of memory that’s just unavoidable.

BLVR: What do you make of the criticism that memoir or personal history is navel-gazing?

MK: It depends how you write. Everybody is navel-gazing. It’s just a question of whether you do a good job at it or whether you’re bad at it. Is it interfering with the story, or does it take you on a digression that is meaningful? Then it’s either that the reader is in the same place as the writer, or the writer isn’t able to communicate something. You can’t figure that one out. Take Nabokov’s Speak, Memory. It’s an autobiography with every particular of his life and childhood, and it’s genius. It’s a complete work of genius.

BLVR: In And the Pursuit of Happiness, you seem most drawn to Jefferson and Lincoln, but you say that Lincoln is the one you’re in love with. Why “in love,” and why Lincoln?

MK: Not what I think, but what most people think, is that Lincoln and Jefferson are the two serious, serious big brains. They are the two people who have the most complexity and resonate the most historically with American history. But why I fell in love with Lincoln and not Jefferson is because with Lincoln there was something about his persona that broke my heart, and I really liked his combination of humor and genius. I don’t think Jefferson had a sense of humor. Or it doesn’t come across in the manner of the writings or the manner in which he’s portrayed. But it comes across very much for Lincoln.

BLVR: You have a forthcoming book project, Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual, with Michael Pollan. The pairings of you with Michael Pollan and you with Jefferson make a lot of sense to me, because I see both you and Pollan as part of a Jeffersonian legacy in your back-tothe-landishness and appreciation for the evidence of the hand on the work or the food.

MK: Jefferson leads you to the world that we’re in now and to Michael Pollan, and I’m lucky that that’s the road that led me to Michael. We just finished the book this week, Food Rules, and, looking at it, we are seeing that it’s a celebration of abundance and of the human presence in creating food, and of people being together and eating together, and that’s really what a lot of my paintings talk to and show: this idea of being part of a group, part of a tribe, part of a family, and you have to sit down together and eat good food together. The writing that Michael does is so important, and one of the things we say is that it makes you set the reset button on time, and it really tells you to go back in time and just see what are those things in history that make sense, and what are those things in your family that make sense, and what are those things outside of you in the industrial world that’s surrounding you. I wanted to give the book out at all the McDonald’s across the country with Michael, but the publishers aren’t amused at the idea of giving the books out for free.

BLVR: Do you feel yourself a part of the American agrarian impulse?

MK: I kill a plant when I walk into a room, so I can’t say that, but I’m the buyer at the market. It’s just a question of being aware. Saying “Eat less, pay more” is an incredibly complicated thing for people to hear. It’s the opposite of the thing that you are pressed to do in your own life. It’s complicated, but the whole idea that you eat less food and it’s really good food and you pay a premium so that farmers can keep making it—I mean, it’s completely about all of life.

III. SCHERZO

BLVR: In terms of others who’ve interviewed you or have written about you, as well as from speaking with friends who admire you and hearing about their mothers who admire you, and thinking about the demographic that tends to show up at your readings, it’s clear that your work appeals to women. This place you’ve come to occupy as a type of feminist icon or a person that women admire—is it something you accept or ever expected or wanted?

MK: I always felt that I would have a certain amount of recognition, but not too much, and that I would be doing my work, and that within a small group of people I would have enough affirmation to continue doing my work, and I guess that’s what happened, more or less. I am very happy to continue just to work and to not have to have any perception of what my place is or what my role is. My place is to just continue exploring what my work is. I don’t want to think about the work representing anything or influencing anybody. “Am I a voice of women?” No, no.

BLVR: OK. We’ve talked about how much you love the act of walking and how important you think it is for the creative process.

MK: For everything. For your mental health. For your everything.

BLVR: And when I read your books, I feel as if the pages are working in a way that the mind works on a good walk, skipping from the deeply internal to the immediately external with seeming abandon, but with a certain cosmic order. Do you ever think about your books as long walks, or do you think about walks as books?

MK: It’s interesting, because I think what happens when you’re walking is that you’re processing stuff in ways that put things in order, and there are more important things or less important things, but you’re not judging what’s important. You see this thing, you see that thing, it gives you a sense inside of great fulfillment, and you go, Oh! Aha! I made a connection that really, really makes me feel good. That’s what’s going to go in the book, also. So the book, on that level, is exactly the same thing as a walk, and, I guess, vice versa, though there’s more planning in the book, obviously, and in a walk you just see what’s going to happen and try not to think. I think I really have that down. I know how to do that. I know how to not judge what I see.

BLVR: Was walking something you had to learn, or was it something that came naturally to you? And I mean “walking” as in the idea of a walk.

MK: I think that I understood as I got older how important it was to me, and I didn’t when I was younger, when I was a teenager or in my twenties. I didn’t say, “Oh, walking is really it.” I identified that as I got older. I said, “Wait, what is this thing?” I do remember my mother walking way ahead of me when we would go shopping or something, at the supermarket in Riverdale. She’d be a block and a half ahead of me with this very charming walk and I’d be a little kid toddling behind her, and I remember the first moments of watching her from behind—which is how I photograph a lot of people, from behind—and just seeing her determined to go ahead, just right foot forward with courage and maybe honor and grace. All those things to a walk. This is also why I want now to go to a music school and immerse myself in music. I think that music really gives you that sense of phenomenal fulfillment. Even listening to music, that’s blissful, but if you’re creating music, the thing you have access to is this sense of great accomplishment and purging of malaise, and it is quite a good thing.

BLVR: I love walking and music as well, and something they have in common, it seems to me, is this sense of beats, this sense that there is a time in which you are proceeding forward, and the time is determined by your feet or by a predetermined meter.

MK: Did you read about the woman who is going to swim from Cuba to Florida, Diana Nyad? She was in the paper a few days ago. She’s swimming sixty hours straight. It’s something that they can’t even conceive that anybody is doing. It’s one hundred miles, sixty hours without a break. Every hour she’ll tread water for a few minutes to get some sustenance and some nutrients. But what she’s doing while she’s swimming to keep herself from going nuts is singing—though I bet she’s singing to herself, because she’s not opening her mouth. And they talk about what songs she likes.

BLVR: I guess swimming can have that rhythm to it, too.

MK: So she’s doing the rhythm and the singing and continuing that way. She’s sixty-one. Not only is she doing something which for a twenty-year-old is difficult, but they say that as you get older, there are different things that kick in that allow you to deal with the difficulties. However, she’s sixty-one years old! It’s mind-blowing, the nature and force of that determination, to say, “Yes, I’m sixty-one. So what?” It’s fabulous. It’s completely demented and completely fabulous.

IV. THE SOLACE OF LEFT TURNS

BLVR: In your work there is an ability to face loss—the loss of your husband and your mother—to gaze into the abyss and then look away and move on. It allows room for sadness and optimism, the humor and the pathos, side by side. When you are addressing loss, are you focusing on the aspects of your individual experience, or the universals of these experiences? Or is it all the same to you?

MK: I can’t know what the universal is, because I’m only one person, but of course there are truisms in the world about life, and that the force of life for those who are still alive goes on. My mother always said, “Where there’s life, there’s hope,” and that’s a monumental force. But I’m talking about it from the personal point of view—my loss, my sadness, my sense of inconsolability; it’s constant. It doesn’t go away, and that’s what so extraordinary: That at the same time you can have such joy in the world and such productivity and such a sense of fulfillment, not one after the other but at the same time. I think that’s how everybody feels, really.

BLVR: Your work can be very personal without ultimately revealing a whole lot, because you’ll reveal but then make a left turn to an artwork or another thought. Is this a conscious decision? Is it meant to illustrate that you find solace in art or in whimsical digressions?

MK: I probably find it too painful to stay within the context of whatever is too painful to me. I’m probably aware that I’m writing for an audience, and I don’t want to become too morose and lugubrious. Then people will think, Snap out of it already, lady. And that’s when you say, “What are the balances of being aware of your audience—being aware that you’re doing a craft while you’re sitting here moaning about something that has happened to you?” That’s just back to navel-gazing. So I am thinking of tempo and of balance, and I’m aware that I want to have a balance of energy, and to relieve what seems heavy and slow.

BLVR: When you say “tempo,” do you mean tempo in a musical sense?

MK: I do. Tempo and mood—I guess it’s all the same. There’s the tempo of changing from something that’s sad and slow to something that’s happy and upbeat, or a digression that is interesting or funny. I guess it is a musical decision on some level. It’s done by ear. You know you’re sick of hearing that tempo, so you need to hear another one.

BLVR: Do you think of the pieces as little musical compositions, then?

MK: I often do. I often think they literally should be— and some of them have been—set to music. I don’t think I’m thinking of them literally as musical compositions, because I don’t know enough to do that, but I’m thinking that there is a musical underpinning to what I’m writing, and also just the delight of the language and the musicality of the language.

BLVR: What would you say are the genres you’re trying to emulate? Where are you taking your tempo from?

MK: I’m probably taking it from classical music. From concertos and sonatas and mainly from vocal pieces. I think for me the piano and the voice are the two most expressive instruments in classical music, but the voice is always for me the number one.

V. THE THINGS THAT BEGIN TO BELONG TO US

BLVR: Your husband died in 1999. While you were successful before that, as a designer and illustrator and collaborator, you were a bit more behind-the-scenes, and his was the name more people knew. You became more well known after his death. What professional role did he play in your life before he died, and how did it change or not change after he died? How did the process or idea of work itself change or not change?

MK: I always think I was supremely fortunate in meeting him when I did, because he had a very strong work ethic and he was very grounded, in that if you have an idea, you can do it. He was fearless in that way. He was both a workaholic and fearless; it’s an incredible combination to have around as an example. So the idea of actually working hard and getting to where you want to go became “Wow, you can do that.” I learned to work harder than I would have—I mean, again, who knows what would have been—but it seems to me that he enabled me to look at my work and think, This can be actualized, as opposed to staying in a dream world. Then as we got older and we worked together, I saw that my contribution to the ideas was very important, and that you needed the ideas to implement—and the eccentricity of our ideas and the spectrum of our ideas and humor was something that was really wonderful and that worked really well together. He was somebody that demanded of people around him that they work hard. It was that you must do a book, and if you can do a book a year, why can’t you do two books a year, and if you do two books year, what about four? So these expectations of productivity were very high, and I think I incorporated that. When he died—when he got sick and he died— I didn’t think I would be able to do anything at all. But then something happened. Again, you know, maybe it’s the momentum of time—that as you get older, your work gets more well known. Maybe I would have been more well known in these ten years if he had lived, because I would have continued working and the projects that were really amazing would have come. That’s part of the luck: the projects that came after he died. But I felt that somehow I had really internalized something. It was not somebody else’s energy. It was my energy. There it was to use, and it felt natural.

BLVR: Do you think that part of your mourning was working?

MK: Yes. Part of my surviving and not going completely crazy and descending into some dark abyss was working. I think to be occupied is 90 percent of the battle in terms of understanding how to keep yourself sane and happy. Not just sane but happy, and with this sense of self-esteem and fulfillment. I understood that being engaged in projects with other people, where your brain is focused on solving other problems, was extraordinarily important— and still is. I mean, the days that I’m not painting I get very cranky. I can see myself getting into sort of a cranky stew even though I have other things to do and I am busy and I am fine. Then when I’m back in the studio painting, I say, “Oh, I see.” So you have to keep doing it.

BLVR: What do you think he would say if he could see you now? What would you say in response?

MK: God. I think he’d say, “Why are you wasting your time here with an interview?” [Laughs] It’s hard to say. The thing about being with somebody who’s so brilliant is that you just don’t know what they’re going to say, and that’s what’s so amazing: you just don’t know. But I often think that he’d just say, “Keep on keeping on.” I think he’d be pleased.