Toward the end of Persepolis II, the second installment of Marjane Satrapi’s ongoing project of autobiographical graphic novels, the author/narrator spends seven months designing a huge theme park based on Persian mythology. She takes her Tehran-based Disneyland to the Deputy Mayor’s office, where it is rejected—luckily for us, because shortly after that disappointment, Satrapi left Iran for Paris, a final emigration that led her to discover Art Spiegelman, the power of comics, and the development of her own method of storytelling.

Satrapi’s graphic novels are the opposite of mythology; personal and honest, they humanize the Middle East through memoir. Hemmed in by the tyranny of the mullahs, Satrapi’s life is nevertheless cosmopolitan, politically engaged, culturally sophisticated, and, like those of all adolescents, deeply conflicted. Today Satrapi lives in Paris, where she remains deeply conflicted, caught between home and exile, East and West, now all the more complicated by the geopolitics of the post–September 11 world.

The following interview took place at a brasserie around the corner from Satrapi’s studio in Paris, where she is working on an animated feature film adaptation of Persepolis. She smoked a lot, talked fast, and tied together a multitude of tangents.

—Joshuah Bearman

I. SUPERHERO STORIES

THE BELIEVER: Your books recently came out in Israel and were well received.

MARJANE SATRAPI: In a place like Israel, they’re very concerned with Iran, so there’s a lot of interest. Especially with what’s going on there now, the new government and all. So they want to see what this Iranian from France has to say in her comics. I guess that’s good. Now the books are coming out in other countries. And each time, they discover something different to be interested in.

BLVR: I think the broad appeal probably has to do with how your stories humanize a mostly unknown place. The popular notion about Iran is as a terrifying theocracy, brimming with lunatics who want to kill the West. As if every single Iranian has a bunch of flags in their closet, all lined up for the next Death to America/Israel protest. And then your books come along and tell a different story, about people with the same problems, sorrows, and joys that we have. And fears—here are Iranians who are just as afraid of the Iranian regime as we are.

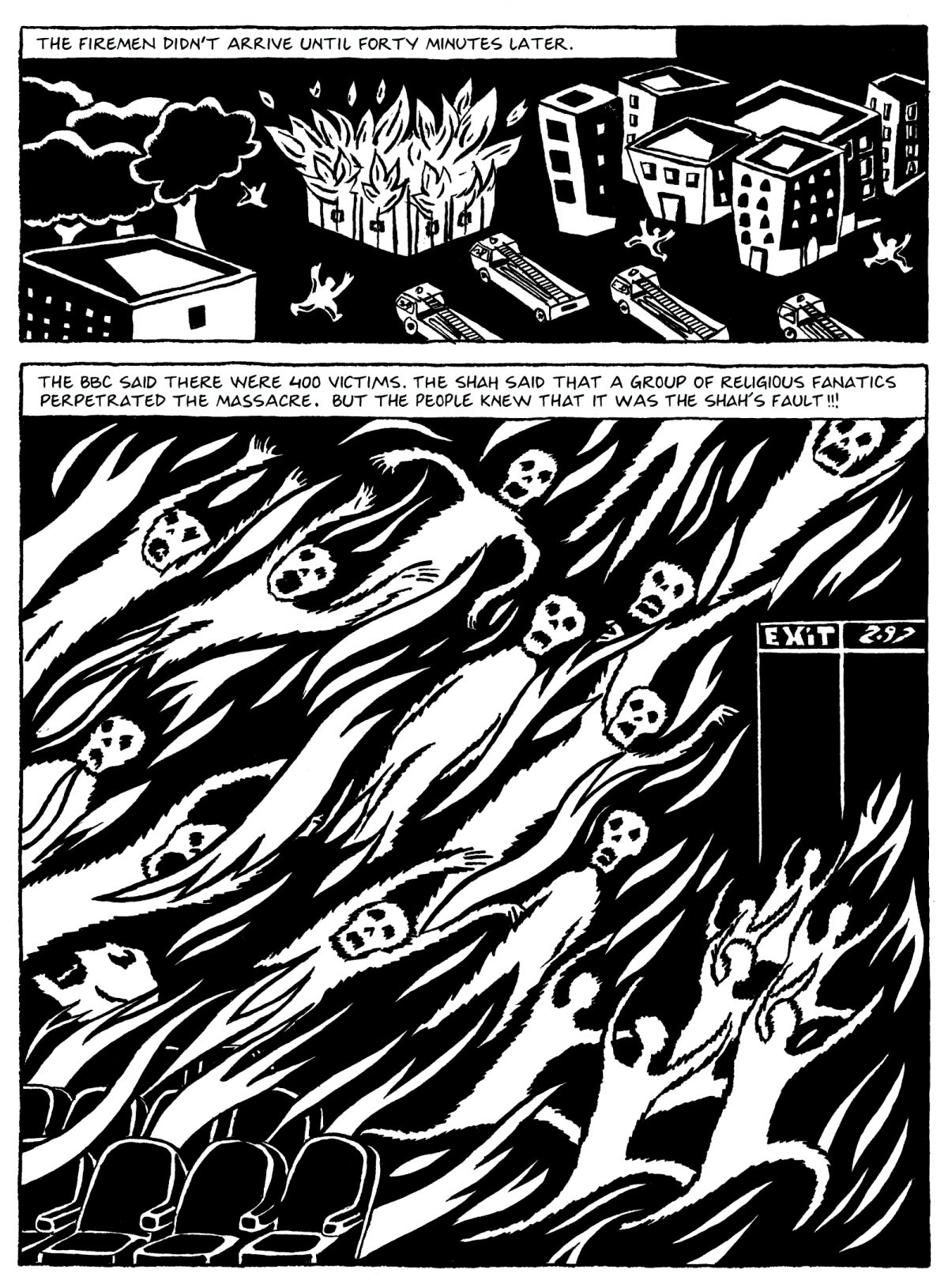

MS: Absolutely. Here’s the problem: today, the description of the world is always reduced to yes or no, black or white. Superficial stories. Superhero stories. One side is the good one. The other one is evil. But I’m not a moral lesson giver. It’s not for me to say what is right or wrong. I describe situations as honestly as possible. The way I saw it. That’s why I use my own life as material. I have seen these things myself, and now I’m telling it to you. Because the world is not about Batman and Robin fighting the Joker; things are more complicated than that. And nothing is scarier than the people who try to find easy answers to complicated questions.

BLVR: Superhero stories are the original territory for comic books, with good versus evil. So by deepening the story, are you also commenting on the format?

MS: I just think that comics have always been more than that. They really haven’t always been superheroes. And today, of course, people like Art Spiegelman have shown how truly powerful comics can be. Joe Sacco uses comics as political reporting. So comics are just another medium to express yourself. It’s not cinema; it’s not literature; it’s just something else. It has a specific requirement, which is that images are used to tell the story. There are lots of crappy movies, with guns and action and Arnold Schwarzenegger or whatever. This is not the movies’ fault. It’s the fault of the directors who made those movies. Any medium can only live up to the strengths of the people working in it. If it’s been used to tell bad or boring stories, it’s not a problem with comics; it’s a problem with the writers of those comics.

BLVR: Do you think you reach a broader audience because of your use of comics?

MS: Maybe. Because of the images. You see a picture and you understand perfectly, immediately, the basic thing that’s happening. It’s probably more accessible because we are in a culture of images now. People are used to seeing stories that way. They understand looking at pictures.

II. STUCK IN THE MIDDLE

BLVR: Was there at a point at which you knew you wanted to draw a memoir?

MS: I always thought about it. And then there was a point that I could imagine what it was going to look like, although I didn’t know when I sat down what exactly would appear on the page. Sometimes you’re surprised by your own stories. There were things I didn’t plan, or didn’t really remember at first, that just came out.

BLVR: Your books are a kind of cultural bridge. If there were only text, maybe they’d be less able to serve that purpose.

MS: Probably so. It would also be harder for me. If I were to write a memoir with words, I’d have to figure out a way to express verbally an image I have in my mind. In my case, it’s easier to draw it. And words also are filters. They have to be translated. Even in the original language, there is interpretation and some ambiguity. If there’s a cultural difference between the writer and the reader, that might come out in words. But with pictures, there’s more efficiency.

BLVR: You visited West Point and made a cartoon about it for the New York Times Op-Ed page. You expected one thing—angry drill sergeants, a summary execution for your antiwar views—but found something else. It seems like that’s a synopsis for a lot of your work.

MS: Yes, I learned a lot. In France, all you hear about is how, after September 11, all Americans supposedly eat Freedom Fries. And they don’t drink French wine or whatever. The news here makes it look like all Americans are fat patriots with boots who want to start war all over the Middle East. Of course, some people did start talking about Freedom Fries. But in France, you didn’t also see the Americans who opposed Bush. So when people here talk about the stupid Americans, I find myself defending America. I say, no, they’re not all like that. America’s ideals are still strong, and so on.

BLVR: When you’re in America, you probably wind up defending France.

MS: It’s funny that way. And everywhere I have to defend Iran. Because Iran is not understood at all, especially in the U.S.—I mean, come on! Bush with his Axis of Evil, and they want to kick our ass and all that. Just like in the U.S., where the people are not all represented by Bush, in Iran the people are not represented by the Ayatollahs. So I’m stuck in the middle.

BLVR: Like a U.N. goodwill ambassador.

MS: Now my job is to defend everybody. But I don’t mind. Because I travel, and I like to talk to people and really listen to them. And I have no prejudices. I figured out a long time ago that, whatever I think I know, I don’t know anything. Once I realized that, I really started learning. That’s a great strength: I know that I don’t know. There are some people in Iran who are fundamentalist and others who are not. I have very good Israeli friends. And I have very good American friends. We come from different cultures but share points of view. It’s humanism, which we’re steadily losing. That’s what the comics are about in a way, trying to stop that loss.

BLVR: That’s something that your books address indirectly. Was that intended?

MS: Absolutely. Of course. The cultural similarities. The human similarities. Maybe the biggest problem is that there’s no empathy. Nobody puts themselves in the place of others. Everyone thinks they are the only one to suffer. Or that they’re the only ones who like ice cream or take their kids on vacation. People are always so shocked to find out that in Iran we knew about punk rock. Sometimes we learned about it before Americans. I have friends from the Midwest who found out about the punk movement after I did. It also shows the power of anecdotes, a small story, to explain the bigger picture. So I worked in anecdotes of my own to comment on the world. Because the world is not decided by George Bush and Saddam Hussein. They make things happen in the news, but that’s not real life. Real life is you and me.

IV. HUNGER EATS CIVILIZATION.

BLVR: You use comics, a fairly simple format, to tell a nuanced, complex story. And yet somehow, the entire narrative machinery of giant news-gathering organizations and most movies and magazines seems to miss that nuance and complexity. It’s a weird reversal: the front page and cable news, where we’re supposed to learn about the intricacies of world affairs and politics, have turned into a comic book, while you’ve turned a comic book into a window on the world’s intricacies.

MS: It’s because my kind of story doesn’t sell news. I have stopped looking at the TV. Facts and consequences are all they say. Which is never the whole story. The whys are what’s important. But violence is news, to a certain extent, and people don’t want complicated news. Because as soon as you realize things are complicated, your life becomes more complicated.

BLVR: It must have been strange for you to watch the recent French riots, since the crisis surrounds identity and East and West, and you straddle both sides. The riots got folded into the grand plot of the clash of civilizations, the first flashpoint of which was 1979 in Iran, the centerpiece of your memoir. It’s like you can’t escape that story.

MS: Unfortunately. And it’s mostly a made-up story. It was incredible to see how it was created here. All over the news: Muslim rage or whatever. The rioting was not about being Muslim. These people have not been able to integrate. So if they have a crisis of identity, it’s forced upon them. If, after three generations of living in France, Arabs are still called Arabs and not French, then of course they will be angry. People ask why the Arabs don’t consider themselves French. Well, it’s because the French don’t consider them French. Then you had the Ministry of the Interior talking about cleaning the scum off the street. That doesn’t justify the violence—they don’t have the right to burn cities—but it explains what happened.

BLVR: What about the mission civilatrice?

MS: Yes, that exists in theory. But it’s a question of money, my dear. Immigrant economics. I never had any problem with the French, but I come from a wealthy family. I’m educated. I live in a nice neighborhood. So they don’t care about me. If I had no money or education and lived in the cité, then I’d be a problem. Racism is not nearly as important as poverty. That’s the same around the world. What look like ethnic problems are really economic issues. If you look closely at all these conflicts around the world, they come down to poverty and economics and resources. The more poverty, the worse the war. Hunger eats civilization. The West is not hungry; that’s why they can say they’re so civilized. Civilization is the biggest bluff!

BLVR: I covered the last American presidential campaign. In the process, I talked to a lot of people. I’d say about a quarter of the people I encountered had a politics motivated entirely by the Book of Revelations.

MS: But that’s not just a problem with America. The crazy people are not based in one country. They’re everywhere. George Bush talks about the Axis of Evil. What’s the difference between that and the mullahs talking about the Great Satan? They say, “read the Koran.” The other one says, “read the Bible.” The mullah says he’s the best friend of God, and George Bush does, too. The problem is that no one has really seen or talked to God, so who can really vouch for what God says? But the mullah is a religious man. He’s supposed to talk like that. Bush is the president of the world’s leading secular democracy. This is not normal.

BLVR: In the Middle East, the apocalyptic Christianity of the Bush administration has political implications. There are people in the United States who want instability in Iraq, Iran, Israel—all over, really, because they see it as a sign of the Tribulations.

MS: I never understood that apocalypse stuff. They want the world to end tomorrow. Why? Life’s already short. You’re going to die. Why hurry? This religion on the rise everywhere really scares me. Are we going to burn old ladies again? Ten or fifteen years ago if you said you didn’t believe in God, no one paid any attention. Now it’s a political statement somehow to be atheist or agnostic. When people ask me what is my religion, I say I don’t have any. And some people are shocked. They don’t understand. I say I don’t need it. I respect humanity. That’s my religion. I can’t stand these religions that are really businesses. So much money everywhere that’s going to buy a really nice house in heaven—or what? I don’t get it.

V. DINNER WITH ART SPIEGELMAN

BLVR: What do you think about the new president of Iran?

MS: He follows the whole world’s movement toward religious extremism. And when the leader of the world’s greatest democracy is Bush, then what can you expect in a theocratic dictatorship like Iran? The whole region is run by soldiers or mullahs. In Iran there are social problems behind extremism. Iran is the third-largest producer of oil, but the country has terrible poverty. And so the mullahs come along and make promises. And they use the U.S. as a scapegoat for their problems. Their two biggest enemies, Saddam and the Taliban, are gone, and only the U.S. is left. So the anti-American rhetoric gets louder.

BLVR: Were you optimistic about the reform movement in Iran?

MS: Who can be optimistic these days? Everyone is losing their head. No one wants to talk anymore. The whole world is run by a bunch of cowboys. I just can’t be optimistic the way things seem to be going. I’m extremely worried. Because you can see from history that things can go wrong very fast. Think about how World War I started.

BLVR: With poor statesmanship and miscommunication and—

MS: And that was when there were diplomats. Now Bush throws away fifty years of diplomacy just like that. So how can I be optimistic?

BLVR: But then again, your books are rooted in optimism.

MS: Well, of course I do have a little bit of hope. Otherwise, I would just take a shotgun and end it all now. Since I’m alive, I’ll always hope that a miracle could descend on us. My intellect sees no way out, but my instinct for survival is hopeful. It says: let’s try. The day that I don’t have that anymore, I swear to God, I will commit suicide. That’s something I do want to communicate to the readers. Not the suicide, but the hope. What I really believe in is good people. It’s that simple. The bad ones are really crazy, totally out of their minds, and the problem is, you don’t need very many crazies to really screw things up. That’s what gives them their power. But there are more of us, I think.

BLVR: Well, that does sound hopeful. So you must be happy to see the expansion of your medium. If you go into Skylight Books in Los Angeles and other stores, there are shelves of local independent comics that people just bring in and sell. It’s really proliferating.

MS: Yes, exactly. It’s very exciting. I don’t want to be the only cartoonist. There should be many more. I want to see a whole new generation. There are so many writers and filmmakers and photographers in the world. Why not more high-quality cartoonists?

BLVR: I heard that you bet Art Spiegelman that John Kerry would win the U.S. election.

MS: Yes. I lost that one. Had to pay for that dinner. The problem is that wasn’t just with him. I made that bet with a thousand other people, so that was a lot of dinners I had to buy.

BLVR: Then again, it sounds like you are an optimist.

MS: I always want to believe in the best outcome. OK, I guess maybe I am an optimist.