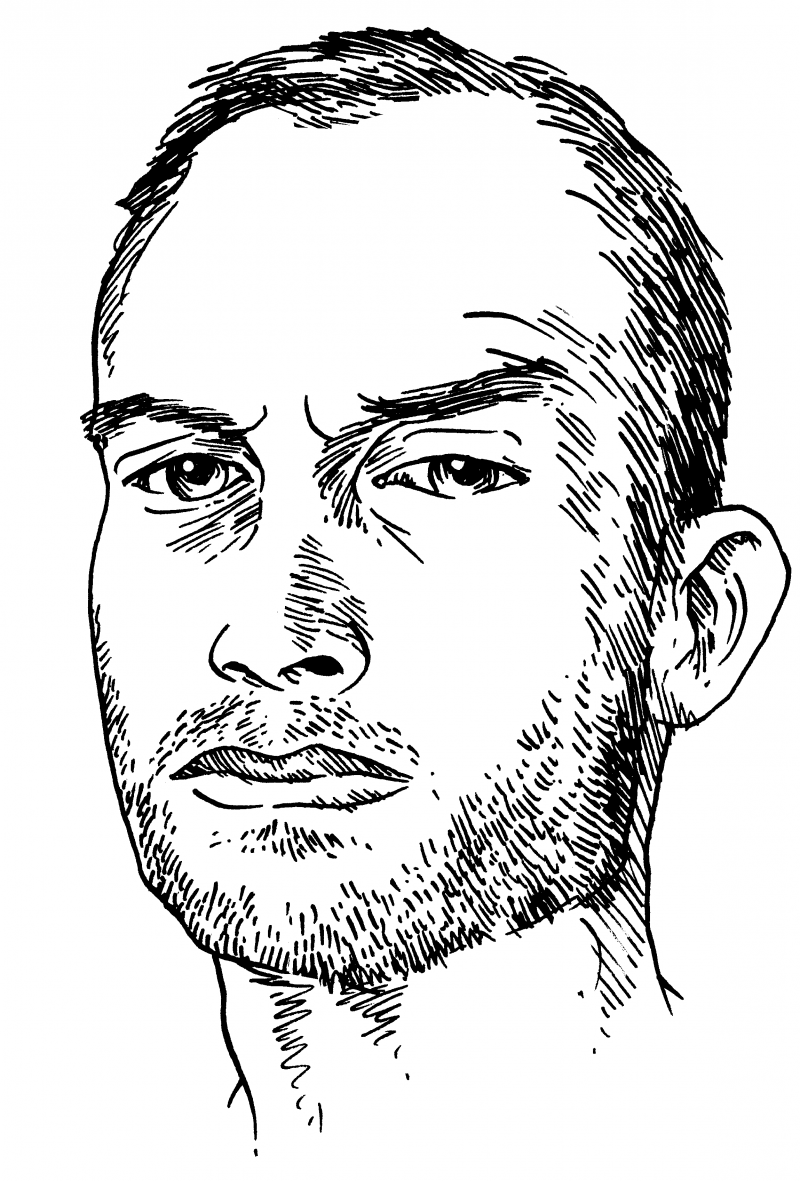

The sculptor, filmmaker, and conceptual artist Matthew Barney is best known for his epic six-and-a-half-hour Cremaster Cycle. Befitting the project’s elliptical nature, Barney undertook the five-part film cycle nonsequentially, starting with 1994’s Cremaster 4 and closing, in 2002, with the climactic convergences of Cremaster 3. As any decent biology text will tell you, the “cremaster muscle” raises and lowers the testicles, regulating temperature to ensure the sperm’s fertility. That, as well as the fetal stage prior to sexual differentiation, is central to much of Barney’s oeuvre.

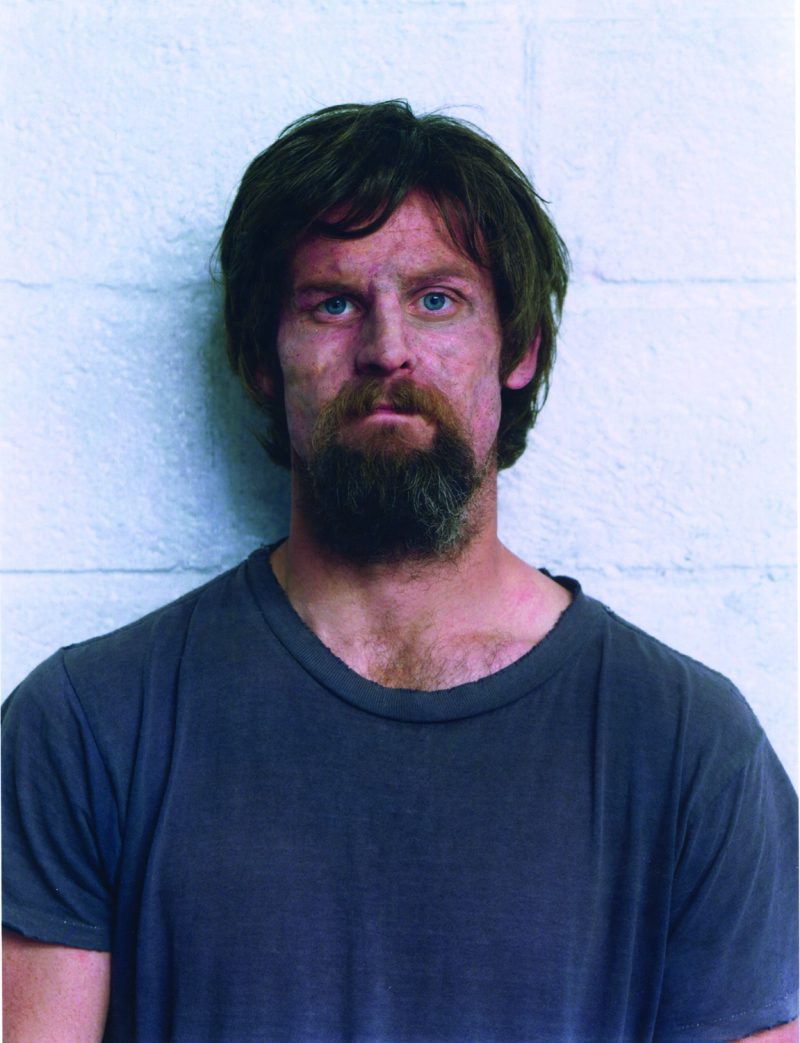

Cremaster’s mostly wordless universe includes, among other things, the Isle of Man, Barney as a red-haired tap-dancing satyr, Ursula Andress in Budapest, a giant Barney with pigeon-tied testicles, Norman Mailer playing Harry Houdini (and Barney as The Executioner’s Song subject Gary Gilmore), a zombie horse race, a Bronco Stadium chorus line decked with helium-filled Goodyear blimps, gangsters, a multi-colored ram, vaudeville passages, growling death-metal icon Steve Tucker of Morbid Angel, the Masons, motorcycle sidecar races, a swarm of bees, bucking broncos in a choreographed death dance, fairies, and the Rocky Mountains. In Cremaster 3, Barney revisits past works (Gilmore, the Isle of Man, etc.), also playfully acknowledging his standing in the art world. In the central movement, “The Order,” he echoes the five parts of the cycle, while conquering Frank Lloyd Wright, scaling the interior of the Guggenheim: the Super Mario, or Dante-style game, pits a pink-tartan-kilt-clad Barney against a number of obstacles that include the Vaseline-scooping Richard Serra, double-amputee model Aimee Mullins as a shape-shifted cheetah, and New York hardcore bands Murphy’s Law and Agnostic Front (complete with slam-dancing fans). The film also stars a Chrysler Building crash-up derby and an Oedipal battle between Serra (as Hiram Abiff) and Barney (as the Entered Apprentice). When Cremaster 3 debuted at the Guggenheim, in 2003, as a part of Matthew Barney: The Cremaster Cycle, the museum was outfitted with blue Astroturf, echoing Cremaster 1’s Bronco Stadium, the site of Barney’s high-school football games. “There was a conscious attempt to balance autobiographical material against the mythological, and the more intuitive, abstract material,” Barney told me when we first spoke. “It’s not so much about creating a portrait of an individual, but rather a complex, or a system that describes an individual form. Something like building an elaborate mirror over a ten-year period, then arriving at the mirror and being surprised to see your own reflection.”

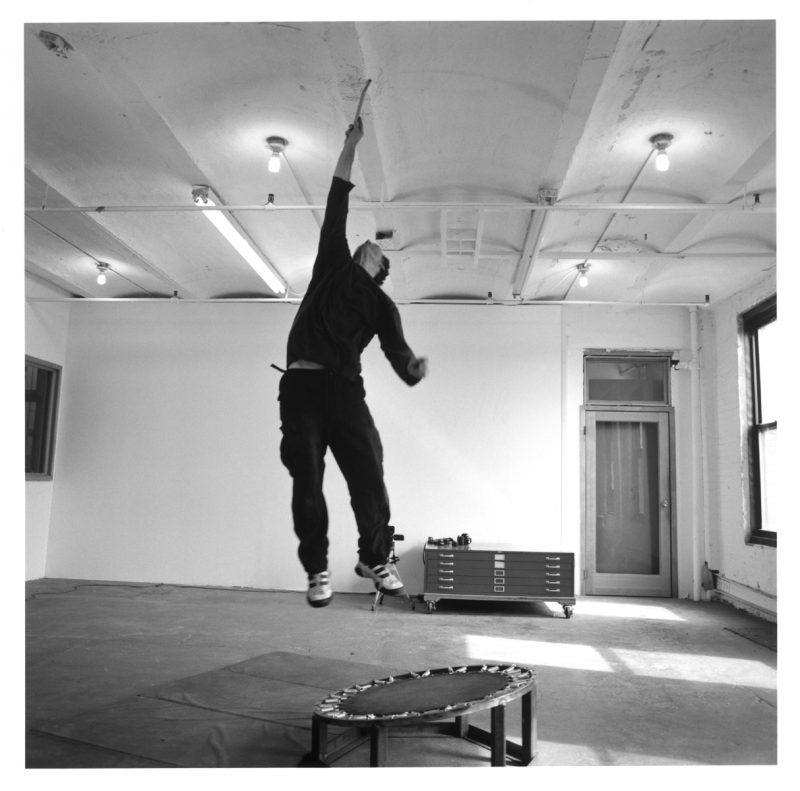

In 2006, Barney released Drawing Restraint 9, a 135-minute film, and part of an ongoing series he began as a student at Yale in 1987. In general, the series finds Barney battling against an impediment of some sort (an elastic band, rope, hockey skates, a trampoline, etc.) while attempting to draw on a wall or a ceiling or other surface. This isn’t always the case: 1993’s Drawing Restraint 7 found limousine-bound satyrs leaving a mark with their horns and resembled Cremaster, at least topically. Or, in Drawing Restraint 3, from 1988, Barney chalked his hands, approached a petroleum wax-and-jelly-cast Olympic barbell, gripped the sculpture for a clean and jerk, released it, and documented the chalk that fell to the floor below the barbell. As Barney puts it, the concept behind the various actions has to do with “the way the body develops under resistance.”

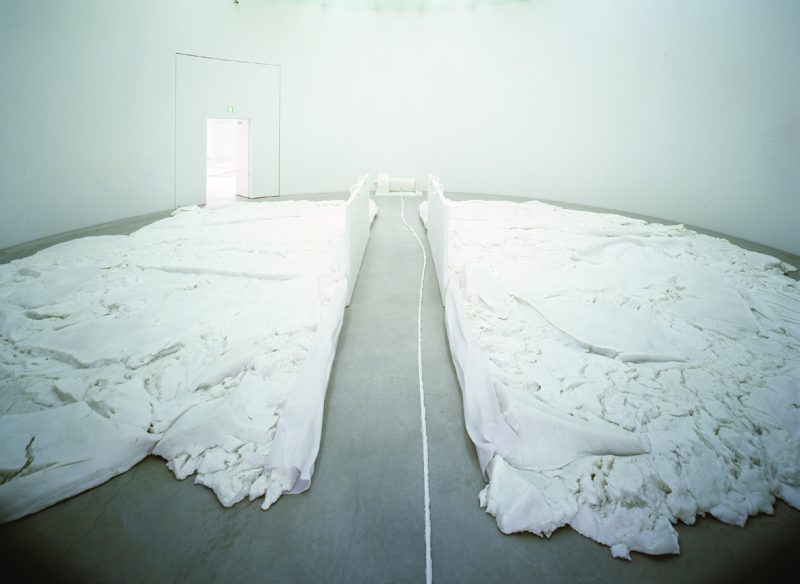

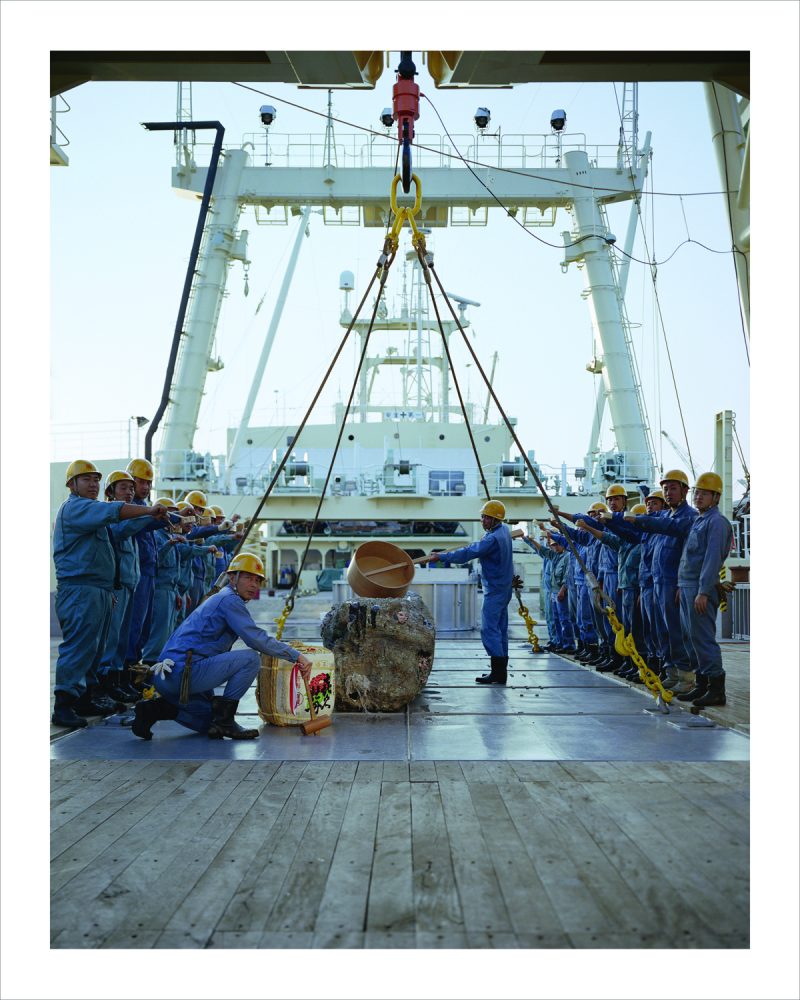

Drawing Restraint 9 is the series’ major statement. Shot in Nagasaki Bay, it slowly unfolds on board the Antarctica-bound Nisshin Maru, a Japanese factory-whaling vessel. Joining the crew, a mysterious “Petroleum Spirit” and a large, mutating Vaseline sculpture of the field emblem are “The Occidental Guests,” played by Barney and his partner, Björk, who also composed the film’s soundtrack. Drawing Restraint 9’s central moment occurs at a traditional Japanese tea ceremony, during which the film’s only verbal dialogue takes place. After the host serves green tea and provides the Nisshin Maru’s history, the two guests consummate a courtship and kick-start a transformation, echoing the shifts of the sculpture on the deck. An exhibition at Barbara Gladstone in 2006 that accompanied Drawing Restraint’s early run included thermoplastic sculptures and casts from the film, erotic drawings, and the remains of a private performance in which Barney, dressed as General MacArthur, jaunted across a field of petroleum jelly. Drawing Restraint 9 shares visual similarities with Cremaster, but Barney sees a crucial distinction: “There was a host and there was a guest and they never become one thing,” he told me. “Whereas the guest in Cremaster is viral, it’s inside the thing, and it becomes part of the thing. It’s a very different model. There are similarities in the works in the way they look and feel, but I think they’re fundamentally very different.” Since the release of Drawing Restraint 9, Barney has performed additional Drawing Restraint actions. All in the Present Must Be Transformed: Matthew Barney and Joseph Beuys, an exhibition that links the work of Barney and Beuys, opened at the Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, on October 28, 2006, and will head to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice in time for the 2007 Venice Biennale.

I first spoke with Matthew Barney in his New York Meat Packing District studio, where we drank coffee from Styrofoam cups at a conference table covered in light-green industrial carpet and emblazoned with the field emblem. (Later, Barney mentioned the emblem was accidentally melted into the table with a branding iron.) Our discussion continued over email and at metal shows across Manhattan.

—Brandon Stosuy

I. TRAINING

THE BELIEVER: Football’s often discussed passingly in regard to your practice, but I’d like to delve a bit deeper. You played quarterback for your high school team and later at Yale. That position makes sense.

MATTHEW BARNEY: Yeah, it didn’t take me very long before I started recruiting other people into my projects. Even as a student, I think, it felt more natural to me to try to continue this team effort.

BLVR: I’m interested to know how football relates to the work.

MB: Every year that goes it by it’s harder to recover the memories, but it continues to be relevant to me. Preparing the Drawing Restraint exhibition, and looking again at these pieces from ’87, ’88, ’89 definitely brought a lot of that back, and made that initial impulse more visible. Those experiments I was making with performance early on in school made me realize I had a pretty fine-tuned relationship with my body, and I recognized at a certain point that this relationship had an affinity with the artmaking language. That continues to develop; I’m still using my body in my work. Most of these impulses evolved out of my experiences with football, both on and off the field. Most significantly, from the training regimen, the preparation—particularly when the work started to become narrative. The competition, or the actual game, was less profound for me. That said, there’s an interesting combination of internal and external experience: simultaneously being inside and outside of yourself. Playing together as a unit with eleven players, in a field of twenty-two players, while having a very internal experience. But I think trying to describe the more hermetic training space became the beginning of the storytelling in my artwork. Trying to diagram that internal space, both as a structure for a story, and in other cases literally describing that space itself as a story.

BLVR: Your art includes a number of football references—Astroturf, Bronco Stadium, and the Drawing Restraint actions, etc. Moving an object that’s offering resistance reminds me of players driving those—what are those called?

MB: Blocking sleds. Yeah, there are these things that you take for granted when you’re an athlete. I think as I started using my body in my artwork, I was more or less just continuing to do what I knew best. I think I was still taking for granted what it all meant. Eventually, biological models were used to organize these impulses into metaphorical language. These models were to do with hypertrophy: the way the body develops under resistance. What came later was the narrative, where there was an attempt to locate an intersection between a physiological or biological space, and a more psychological space.

BLVR: The body—your body, specifically—is a huge part of your work. Have you ever thought about what happens when you get older and are perhaps unable to exert yourself as much as you do now and have in the past? Will you adapt the work? OK, hopefully this won’t be for a while. [Laughs]

MB: I think it’s probably not that far off. [Laughs] I feel like that’s already in the work, but it doesn’t tend to be expressed through the characters I play. Often the characters I play are connecting spaces through some sort of movement under resistance. I think the larger form often confesses to some sort of entropy, though that could just as easily be expressed by my own decay. [Laughs] This past summer, I performed a piece in San Francisco that I was more worried about than any of the other endurance actions. It’s called Drawing Restraint 14 and was a climb up and under the skywalk in SFMOMA, which is five floors high over the lobby floor, ending with a wall drawing under the oculus. I used a straightforward hand-over-hand technique; I trained on the sprinkler pipes here in the studio, but the pipes under the skywalk at the museum were significantly fatter. This required more hand strength, and made the climb much more difficult. So with this one, I felt the limits of my strength. It might be a pretty feeble-looking drawing.

BLVR: When you’re working on a film or an endurance action, do you generally have to beef up your workout schedule? Like for Drawing Restraint 14, making sure your arms are especially strong.

MB: With something that direct, yes, I would train for it in a specific way. Most of the projects have had some aspect within the story that I need to be in shape for, and require some kind of training; but what brings me back to the weight room is more to do with finding my center. It’s how I found it when I was twelve years old and it’s still the only way I know how to do it. It has been the most consistent thing in my life, actually.

BLVR: Are you into those NFL highlight films?

MB: Yeah, those NFL Films are great. What’s probably most significant about them, in terms of the way they influenced filmmaking, is the way they brought the individual character out of the chaotic mass of people. This brought a kind of psychological dimension to the viewer. Before NFL Films, the games were described by an upper three quarters angle, maybe from one sideline, and occasional close-ups. These guys approached the game completely differently. They turned sports photography into a team sport. They’d go out as a squad with one camera responsible for one sideline, one camera would be responsible for the other, not just showing the game, but showing the reactions of the players and coach. Another camera would end up in the rafters with an aerial view, with others in the end zones and up in the crowd. Both exhaustive description and intimate nuances were new to sports broadcasting. I feel close to their way of working, but I think I approach it from the opposite end; I’m not really that interested in rendering characters as emotional entities, but rather giving the emotional agency to the environment. In this case, the stadium. I would start with the stadium as the main character, where for NFL Films the stadium is always part of the chorus. There’s also this way of describing conflict in an operatic way—that’s one of the reasons why metal is so interesting to me.

BLVR: You often reference punk and metal in your work—for instance, Murphy’s Law and Agnostic Front in Cremaster 3 or Steve Tucker and Dave Lombardo in Cremaster 2. I love watching the kids getting ready to slam dance in Cremaster 3—that overlapping with the Playboy Rockettes. There are a number of younger artists working with punk and metal (and, well, goth) in a manner that resonates with your practice. I’m thinking especially of Banks Violette, who has been casting in salt, come to think of it, and also Matthew Greene and Sue de Beer. The aesthetic’s different in most cases, but do you see them, somehow, as descendents?

MB: I’m not sure.The feeling I got from the last Whitney Biennial was that there were a number of pieces that had to do with the artist as outsider, and these subcultures like metal, or a general abject sensibility, were being used to describe an outsider culture as a way of defining the role of the artist. I guess that’s not really my interest in metal, or the extreme music scene—my interest has more to do with it as an abstraction of conflict. There’s a way that conflict becomes abstracted into the architecture that interests me. Something to do with the relationship between the amplified music on stage,the active mosh pit, and the passive audience beyond the pit, and maybe even more to do with the trench between the stage and the pit, where the security guards are stationed to remove people from the crowd.That same trench is used to protect the performers in other concert situations.With extreme music shows, it functions differently, more like an overflow valve in a bathtub.

BLVR: Do you listen to metal when you work out?

MB: I don’t anymore. I used to… I don’t think I listen to music as much as I used to,to tell you the truth.I live with a musician and I’m often surrounded by the music that she’s researching or listening to… and then the people who work in the studio tend to have a range of musical taste… so by the time I actually have time to sit down and listen to what I like to listen to,I kind of enjoy the silence.

BLVR: All of this in mind, you don’t fit the common perception of the artist. In fact, I’ve had friends refer to you as a “man’s man.” [Laughs] I realize that’s a limited conception of art and the artist, but if I ask my dad about art, he’ll think of Warhol in his silver wig, or whatever. Do you ever feel like an atypical artist?

MB: I felt that way more when I was younger and just starting.

BLVR: Have you seen Art School Confidential?

MB: No.

BLVR: In it, this hunky guy show up to class and the typical art-school kid says something like, “Who’s that weirdo?” It turns out he’s an undercover cop.

MB: [Laughs] That’s funny. I think over time you become an island, right? Then questions like that become less relevant. Not because situations change, but because you stop paying attention, not necessarily to the community, but to those sorts of expectations. But certainly as a student, when I had just stopped focusing all my energy on sports, and began making art, I found myself surrounded by a bunch of people from the graduate school who’d already developed a language and were truly committed, and I think I felt a little like the odd man out in that situation. But that changed.

II. LOVE STORY

BLVR: Very few critics have engaged Drawing Restraint 9 as part of a series. Are you bothered by people fragmenting what’s perhaps intended to be seen as part of a longer narrative?

MB: Well, that happened a lot with Cremaster because they were released in the order they were made. I also tried to resist talking too much about them until they were all finished, which I believe created some friction around the dialogue surrounding that project. It’s interesting now to watch the Cremaster Cycle come back year after year in Germany and France. There are a handful of places where they’re showing it nearly once a year—not so much in the States. I hope this continues to happen. I think that with each year that passes, the piece is dealt with for what it is and becomes freer from the distracting heat that surrounded it when it was shown as a survey exhibition at the Guggenheim. I think the same thing could happen with Drawing Restraint 9, eventually. On the other hand, Drawing Restraint isn’t a cycle—it’s an ongoing project.

BLVR: Is there an end in sight?

MB: I don’t think there’s an end in sight. They have functioned for me in the past as intervals, really. They were always done between other, larger projects. I think it’s useful to me to feel like I have something that I can come back to… to find a center. This is Drawing Restraint 6 [points to marks on the ceiling], which I reperformed last year, and it felt so good to make a piece in a couple of hours. It was really refreshing. And after Drawing Restraint 9 was completed I’ve done four more. They’ve all been fairly provisional… quick setups.

BLVR: Does it bug you that people have criticized Drawing Restraint 9 as Orientalist or for fetishizing Japanese culture?

MB: I was paying more attention to that response in Japan, for obvious reasons. I could feel a lot of apprehension during the period we were over there installing the Drawing Restraint exhibition at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa. During this time, no one had yet seen the film, and the people within the museum and some of the press that had been coming around taking interviews were starting to express a similar fear. I think they feared that this thing was going to be a piece of chinoiserie. After the screenings, I was hearing from those people that they were all feeling quite relieved that the Japanese cultural references were handled in a way which was more natural than they expected. There was a feeling I had over there,making the film, that was very different from the feeling I would have, for instance, in Utah, a place that I felt was a part of me on some level.And even going to Budapest, a place that isn’t part of my heritage in the same way, still felt familiar by comparison, by virtue of belonging to the West. Either way, I felt like my work could inhabit the place and become a part of it. I never felt that way in Japan. So I think this piece has been about that in a certain way, about going to a place that isn’t mine and adjusting my approach, which is very interesting for me… to accept this guest role in relationship to a host environment, and to stop thinking in terms of a morphing with the host. That my language and the site would remain separate,this really became the program for the piece.

BLVR: You were on a self-contained ship. How did the crew react to the project?

MB:Typically with these projects, if there’s a big group or an organization like the Nisshin Maru crew, then there are usually some people who are interested and some who resent having to put their energy into something outside of their job description. This ship is privately owned, but it’s actually operated by the government, so it’s a kind of military situation… very hierarchical.The way that Japanese corporate structure works, it is difficult to have a very accurate read of what everyone is thinking because you understand that someone at the top has said,“this is gonna happen” and everyone else is just following orders. But, you know, the younger guys were more willing to ask more questions and show some enthusiasm. As for the captain, we worked on the ship right before it left for Antarctica on his last voyage before retirement. I felt a little bit awkward about putting him through that. In the end, he came to the opening and was proud of it, which was important for me. I think that’s what ultimately gave us access to the ship: Eventually they felt confident that the piece didn’t have a specific political agenda. Once that was off of the table, I think they realized, at the very least, it was going to be a strong portrait of the ship. And these men are very proud of this ship.

BLVR: So they were afraid you were going to make some political anti-whaling statement?

MB: Oh, yeah. I made multiple trips to Japan… first just trying to get into the office of the Japan Whaling Association. Everything about that ship is undisclosed. It’s an extremely controversial piece of marine architecture. You’ve seen the Greenpeace footage, haven’t you?

BLVR: Sure.

MB: In the Southern Ocean every winter, it’s always about that ship.You know, Greenpeace hunts that ship. When it returns to port there’s a Japanese wing of Greenpeace that tries to find them and harass them while they’re unloading the whale meat in Japan.It never ends.So,I think,anybody coming to them from the West is bad news unless they’re from Iceland or Norway. [Laughs] So yeah, it took a long time to gain their trust. We blew all of our preproduction time just gaining access to that ship. But it was interesting, and worth it.

BLVR: There’s physical and subtle gestural humor in Drawing Restraint 9—and, of course, in the Cremaster series.I don’t ever see this discussed.For instance,you try on your new gear in Drawing Restraint 9 and almost topple over because of the clunky shoes. Is that humor intended?

MB: Sure.Yeah, I think physical comedy is really relevant to me. I think about it in terms of the way that there’s a pressure held within the dramatic arc of the film which needs to find a way out. In dialogue-driven films you can relieve some of the pressure through the writing, but I don’t have dialogue, so often violence or humor ends up functioning that way, to bleed off some of the pressure.That’s true, it doesn’t seem to be talked about very often, but I gotta say, a lot of these scenes start out as elaborate sight gags, and are developed from there. I wouldn’t say that the foundation of a scene like that is insincere, but there’s often an absurdity that’s at the bottom of it. A recent example would be the idea of making the twenty-five-ton petroleum jelly casting on a ship out at sea. We were making a much smaller one for an exhibition in Iceland and had a lot of leaks in the mold and the jelly spilled all over the place and it was sort of hellish finishing that piece. Moving all the barrels all around and having jelly in your hair for five or six days made me think that either we need to quit doing these pieces or we’ve got to up the ante and make the condition more complicated. I started visualizing the environment on a whaling ship and thinking, well, that environment has got to be worse than this. So why don’t we make one of these pieces on a whaling ship? [Laughs]

BLVR: When it all collapses at the end of the film I thought,“Man, what a cleanup.”

MB: Yeah, yeah, we were given a day to clean it up, too, because they had to leave. Two days later they were leaving for Antarctica for their winter hunting season.

BLVR: In one of the early Drawing Restraints you’re drawing on a wall and you draw this [points to Cremaster/Barney logo on the table], which is the shape of the petroleum jelly casting, and shows up everywhere in your work. Is that what that design came out of?

MB: Yeah, that’s a “field.”The first one was used in Drawing Restraint 1, in 1987. They had slightly different proportions then, but they were used in the same way.

BLVR: How’d you come up with it?

MB: At the time that I was obsessing about hypertrophy and thinking about how the body develops under resistance, as a way of trying to understand the process of making sculpture. I was also thinking about how the stadium or the architecture of athletics could become a character… thinking about how the body could be expanded from its figurative scale and become the container for a story. I began drawing the “field” form as an aerial plan of a stadium, while at the same time thinking of it as a glyph that could suggest this notion of the body with a self-imposed resistance applied as a way to cultivate and harvest creative energy. These two ideas were forming and starting to be clear to me when I started drawing the “field” form.

BLVR:There’s the moment in Drawing Restraint 9 when they remove the piece in the center of the petroleum jelly casting—so flow becomes whole again?

MB:This question started in Drawing Restraint 8: could a drawing restraint project be erotic? Drawing Restraint 9 took it further, questioning if the project could become a love story. It seemed ludicrous to me at the time, even asking that question. I starting thinking about how that could happen: I started imaging that the self-imposed resistance would have to be removed from the field in order for that to happen,and started visualizing the sculptural body going through some kind of atrophy once that restraint was removed, and further, wondering if the tension in the body would be recoverable once the resistance was removed.That’s what the “Petroleum Spirit” character at the end of Drawing Restraint 9 does—he sneaks in and fills that arm of resistance back up; he replaces the restraint. The starting point of the object narrative in Drawing Restraint 9 is this proposal of removing the bar from the petroleum jelly casting, which would drive the rest of the story. The first physical proposal of Drawing Restraint 9 was the simple idea of casting the sculpture at sea on the deck of a ship and trying to anticipate how the condition of the ocean would affect the behavior of the sculpture—how the behavior of that sculpture would be dictated by the weather, and by the movement of the boat. The story of the Occidental Guests—the love story—came after all of this.

BLVR: How did you decide to include your real-life partner as your love interest?

MB: Well, like I said, one of the first questions I was asking while developing the piece was whether the Drawing Restraint language could support a love story. My nature as a sculptor has always been to choose materials for the quality that they possess, either physically or culturally, and to try to avoid manipulating this. I’ve felt the same way when I’ve cast performers for the films. I’d rather find someone that has a specific quality, whether physical or emotional, than to work with actors who would try to project that same quality. For Drawing Restraint 9, the natural way to tell this story was to cast two people who are in love and who are understood to be in love.

BLVR: Did you want it read without the backstory outside the film?

MB: I was interested in describing a magnetism drawing these two characters together, and along their respective paths they would rapidly learn from their environment… in an organic way, but not necessarily a human way. Visually, not much was going to happen: They were going to be transported through a foreign environment to a place that was new to them. They were going to work their way through it, absorbing aspects of that environment, and eventually meet. I wasn’t interested in developing the characters any further than that, in terms of cinematic convention. The ambergris metaphor became useful. Thinking about the aspect of the whale’s diet that is indigestible, which combines with the digestive enzymes inside the whale. It’s a combination of individual parts… the guest/food and the host/whale’s digestive juices never stop being unique, even when they’re coughed up. The transformation takes place in the larger ocean environment where the individual materials ferment and become a new substance that has its own specific quality.

BLVR: This goes back to what I mentioned earlier about people fixating on one part of a project. With Drawing Restraint 9 it’s been this love scene and the transformation into whales via a sushi communion.

MB: I’m trying to think if it’s ever been that way with other pieces. I suppose Cremaster 2 had the bee scene.

BLVR: Had you always planned for the shape-shifting at the end?

MB: Yeah, I was unsure how literal the scene should be, and it took quite a bit of experimenting with the animation team to arrive at a whale anatomy that I was comfortable with, but yes, it was always intended that there would be a transformation.

BLVR: I know you’re interested in horror films. Was the leg-hacking a nod to that?

MB: I felt that if the piece was going to take place on this whaling ship, the extreme, visceral nature of whale processing would need to find its way into the story. This was complicated by the fact that there would be no whale in the story. When I started researching Japanese whaling, I became more and more interested in the more traditional coastal whale traditions and the way that older form of whaling has a very strong relationship to Shintoism. The Japanese believe that the whales are their ancestors, and are felt to be sacred, while at the same time, they have always been a main staple in their diet. I started visiting these whaling villages where the coastal hunting traditions are strong and witnessed whales dragged onto land and being processed—you know, it’s a huge animal. It’s not only huge, but it’s very difficult to handle, so there’s an implicit grotesqueness involved in that process, which feels very natural. It’s not so different from the way some other scenes of violence occur in the Cremaster pieces. I wanted for there to be a very explicit scene that would feel very natural. In contrast to horror or exploitation cinema, it’s not to do with making shocking images, but has more to do with creating a balance within the piece.

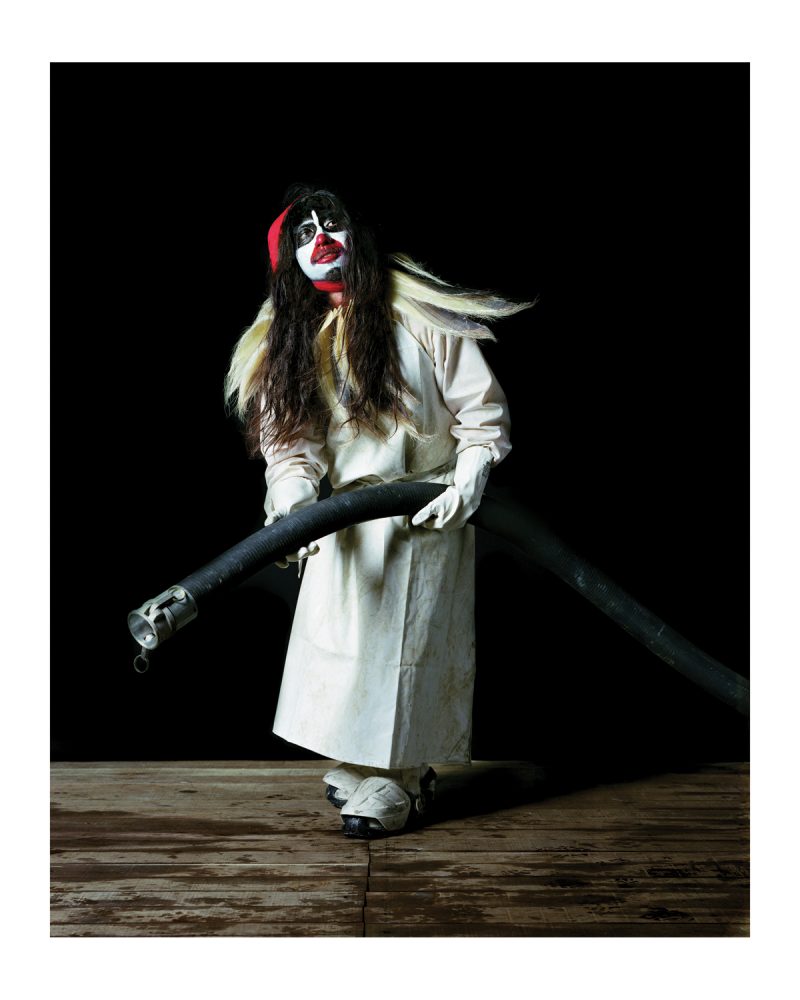

BLVR: When that “Petroleum Spirit” comes on toward the end, I thought… black metal!

MB: [Laughs] I thought I would find somebody on the crew of the ship to play that role… I think I could never really articulate to the managing officer who helped us with our casting needs what the quality of this character would be… what did I tell him? I gave him some ludicrous description of somebody who had a sort of brightness and mischievousness… this is on the Japanese national whaling fleet… They never found anybody. I ended up asking Toshiaki Ozawa, who was shooting a documentary film for Alison Chernick, to play this role. I wanted this character to be like a spirit who would simultaneously be undermining the situation and liberating it, not so different from the way some of the fairy characters function in the Cremaster Cycle. They have a precarious contract with the more primary characters in the narrative.

BLVR: Shakespearean.

MB: Yeah, the chorus… right. But rather than black metal, his face paint comes from the Kabuki tradition, and from a Shinto festival that happens in a little whaling village in Japan, where the use of the black, and the red, and the white is symbolic of the body of the whale… It starts within a Shinto shrine, where the priest makes this offering to each of the hunters. A plate is served with white whale skin surrounding a circle of red pomegranate seeds, forming the cross section of the body of the whale. Small segments of bamboo surround the whale body to symbolize the net used to catch the whale in ancient coastal whaling tradition. And once this offering is made, its remains are paraded through the village by a mob of guys with their faces painted white, black, and red, until they reach the harbor, where they jump in and cast the remains off to sea. There’s a number of these whalespecific festivals in Japan relating to the coastal whaling tradition.

BLVR: So, in the film, then, when they’re preparing that elaborate meal, that’s all part of an actual tradition?

MB: Well, it’s abstracted from it.

BLVR: Right, I imagine they don’t slice their whale meat in the shape of the “field.”

MB: [Laughs] There’s a lot less abstraction in Drawing Restraint 9 then there has been in previous films. I think part of that has to do with that problem I was talking about before of going to a place and feeling like I didn’t really have the ability, or the right, to combine my language with indigenous things in the same way that I had in the past. As a result, I think it’s a much more natural film. There’s a lot less abstraction in it. For example, the ship was used without making any changes to it. If it were part of the Cremaster universe, that ship would have been altered, the crew and their uniforms would have been altered, and so on. It felt to be in the service both of trying to make an honest work in that environment, and also in the service of trying to make a love story—I felt like I needed to rein in those habits.

BLVR: Do you see Drawing Restraint as a departure or movement beyond Cremaster?

MB: I think the real departure for me was De Lama Lamina. In 2004, Arto Lindsay and I went down to Bahia and made a float for Carnival. I was trying to set up a kind of moving set for a narrative that would be filmed during the performance. We went down there with a couple of months of preparation and threw ourselves into the middle of Carnival, trying to pull this off, which was outrageous and frustrating and exciting and a lot of things, but mostly just out of control. But I think what came out of it that was most significant was this idea of approaching Drawing Restraint 9 as a real-world condition that would drive the rest of the project, and would forfeit a bit of control, of the kind we’re used to having with Cremaster. De Lama Lamina was a much more radical experiment, but I think it did get me to this place where Drawing Restraint 9 could be made by taking some of the positive aspects from the Bahia experience and taking back some of the control we had in Cremaster. So it does feel like a departure from Cremaster in that way, and it’s continuing to be a new path for me, which I believe will end up in a place where I’m making live performance. For instance, I’m working at the moment on a small piece for stage in Manchester next summer, which is a project on an opera stage where about eight visual artists will be doing real-time pieces in the range of fifteen minutes each. I’ve started working with Jonathan Bepler, who scored all of the Cremaster films, on some preliminary ideas, and in the studio we’re starting to experiment with large-scale recycling machinery. It’s something that I’ve often felt when I finish larger pieces… some kind of craving for unedited, real-time performance… for something to happen that’s actual. The tail end of these larger film projects is so much to do with editing: so after months of covering your tracks and telling a much different story than you told on set,I really crave a more concrete, immediate expression.

III. THEATRICAL RESTRAINT

BLVR: A friend pointed out to me that, in a way, you make action films about bodily processes. There’s no— or very little—dialogue, but there is a lot going on. Do you view your work as entertaining? How do you think the audience is reacting?

MB: I tend to think of it in organic terms; I tend to think of it as a body. I think a lot of the decisions that are made in regards to duration and balance are about trying to describe an organism that has its own pulse and that has its own behavior. It’s something that keeps me coming back to the filmmaking process. I think working at that scale and working with a combination of media and working with a team of people makes it possible for the form of the project to drive itself at a certain point. Once everybody has put enough into it, the thing starts to have its own needs, its own desire, and its own behavior—and I find that really exciting. I think that can happen in the studio with object-making, but I think it’s often more difficult to get to that point. Ideally, that’s my relationship to the film: It’s not so much about approaching it from the outside and thinking about how it operates, it’s more about being inside the thing and trying to keep up with its demands. Not just in terms of production, but also in terms of the feeling that the film has. It’s difficult to describe.

BLVR: Also, in terms of cinematic languages, there are certain juxtapositions between magic and violence in your work… a sort of stylized violence. There’s a baroque choreography. Are you pulling at all from Hong Kong action movies?

MB: Yeah, maybe this goes back to the NFL Films question in a way: those films manage to do it in a very successful way; the way the conflict is described both in concrete, brutal ways, and abstracted, elegant ways. Yeah, I do like the Hong Kong films, but I find that the films most useful to me are more structural. More like Jaws, or Das Boot, or these horror films, which are isolated in locations where the environment becomes the antagonist. Those films were superinfluential to me in the way they helped me figure out a way to tell the stories I wanted to tell, while continuing to think about them in terms of sculpture.

BLVR: Early on, how’d you decide upon wax and selflubricating plastic?

MB: I started in college using a lot of the materials that are part of the athletic landscape: training processes, the field, the equipment, the padding. This

memory of being within this plastic shell; that it eventually becomes part of your body, or an extension of your body, and starting to use those same materials as a way of building this extended sculptural body. I guess the plastics became a bridge for me between the internal and the external. They were these plastics that began to attract me, that could live inside the body as internal prosthetics and could function outside the body as a prosthetic extension. This became a way of formalizing this notion of describing a narrative that could jump between internal spaces and external spaces and would have a relationship to the body that way. I think it probably became more liberating and more interesting for me when it started to leap in scale from the figurative to the architectural scale, and even to the geological scale. That happened around the time when I started to feel comfortable with thinking about my practice in terms of storytelling. This was sometime around 1992, after OTTOshaft, but before Drawing Restraint 7 was made. I went back to the Drawing Restraint project after OTTOshaft and decided to make a Drawing Restraint that wasn’t a literal restraint, but a theatrical restraint. That was a big step for me—to replace the physical restraint with a more metaphorical or projected restraint carried by a narrative.

BLVR: You’re definitely a storyteller. And there are literary analogues—The Executioner’s Song in Cremaster 2, for example. How does textual narrative work in your films?

MB: The one thing about me is that I’m a very poor reader. Always have been. I can read, but to finish a book is nearly impossible. I can go through a couple pages at a time and that’s it. In one respect, making these large-scale narrative pieces has been about creating a situation where I need to read, as there’s a fair amount of research that goes into making one of these things. Once there’s a frame around what I’m doing, or a frame around the world that’s going to be constructed, the reading becomes more possible.

BLVR: Your work involves intimate activities placed within large-scale structures. What’s the relation between the tiny details—bodies, windows, service doors—and the structure?

MB: There’s this ambition of exploding the body’s scale into an architectural scale or a geological scale. All of the portals and passageways in those spaces become important as a way to emphasize the organic nature of that structure, like orifices moving in and out of that body. If that scale shift is successful, then it liberates the human characters in that story from being the sole carriers of emotion and gives that agency to the architecture, or the container. This is pretty fundamental to what I do, to try to give emotional agency to objects… to these larger structures.

BLVR: Is that why you use something like the Chrysler Building, something that had a narrative already built into it?

MB: Yeah, it has its own myth, so as an object, it already has a kind of behavior. Much like the Celtic locations: the Isle of Man, the Giant’s Causeway, or Fingal’s Cave. With Cremaster 3, one of the things that interested me most was working with something that was so iconic that, to a certain degree, it couldn’t be abstracted very successfully. The Chrysler Building is like that, as is Richard Serra, in a certain way.

BLVR: So, at the end of the day, do you view yourself as a sculptor or a multimedia artist?

MB: I would identify myself as a sculptor, but at the passport desk I would put “artist.” I think I’ve always identified what I do to be in the tradition of site-specific sculpture, including the films. There is a precedent for all of this stuff with land art, performance-based sculpture from the late ’60s and early ’70s. As it was developed, the Cremaster Cycle was visualized as an earthwork, very much in the tradition of [Robert] Smithson’s site-specific and nonsite works. It was visualized as a five-part sculpture in the landscape, with a narrative holding it together.

BLVR: When you’re doing exhibitions of the sculptures from the Cremaster films—if someone’s never seen the movies and views those separately, can they get the work? How do you view those objects in relation to the actual films?

MB: Well, for me it’s harder to separate the things, because they are part of the same universe, but those objects for me are narrative sculpture and they’re drawn from, or are distillations out of, this story, which was written first. Some of those objects are distilled down further, and are more abstract than others. They can exist independently from that source, but they’re never going to stop being connected to it. At the end of the day, I don’t think that’s so different from the tradition of early mythological paintings. The painting functions with or without an explicit understanding of the narrative.

BLVR: Do you think your work’s difficult?

MB: It’s difficult to make. But no, I don’t accept that it’s difficult. In fact, I consider it to be relatively generous. Or at least there’s a generous amount of information available around each project. I’m thinking of the secondary and tertiary forms beyond the film and sculpture that help describe the intention of the work… the photographic works and drawings, and the books and websites, for example. That said, as an art fan, I like a lot of work that I consider not particularly generous in those terms. I’m thinking of more enigmatic work like that of Bruce Nauman, Paul Thek, or Hans Bellmer that exists only as primary form. On the other end, there’s someone like Joseph Beuys, whose works are plenty enigmatic, but supported and described by loads of talking and lecturing. His intentions were always made very clear. Nancy Spector has put together an exhibition in Berlin of works of Beuys’s and mine from the Guggenheim collection. During the preparation of this show, it’s been interesting for me to look carefully at his work again, particularly with my interest to return to live performance. I guess your question becomes complicated when you start comparing visual art to cinema, which happens for obvious reasons with my work. I believe they are two very different kinds of experience.Visual art tends to reveal itself more slowly. Traditionally, one would revisit an artwork again and again, and consider other works by the artist before a meaningful relationship is made. There’s an expectation with cinema that the work reveals itself in one viewing.

BLVR: And really, for all the purported difficulty, I’ve seen some Matthew Barney fan sites—people shave the “field” into their hair.

MB: [Laughs]

BLVR: Final question: architecture’s crossing more and more into the art realm… Would you ever want to build inhabitable architecture?

MB: No. I’ve done some renovations and they have absorbed me in a way that scares me. I could get lost in something like that.

BLVR: Building a deck for forty-five years. [Laughs]

MB: Yeah, I’d probably end up like one of those dudes out in the desert who starts a castle out of Coke bottles and never finishes the thing.