Over a year ago, a mutual friend let the artist Michael Smith know I was interested in doing an interview with him. The friend showed Smith the previous piece I’d published, an interview with someone also named Michael. Smith’s only response, as far as I know, was “Which Mike is he going to interview next?”

Before long, Smith invited me and the friend to sit in his living room, which had an armchair and a television and several small paintings resting on a shelf he’d installed near the ceiling. Smith talked about the walnuts he’d been putting in his oatmeal and asked what the protocol was for throwing away old batteries. He talked about studying painting when he was young—before the performance work, the videos, the installations, the drawings; before the character of Mike or Baby Ikki ever stood onstage in front of an audience—and about how the head of the Whitney Independent Study Program let him stay for an extra semester because he was so tidy. He liked to sweep, he said. And from what I could tell, this was still true. His house was very tidy.

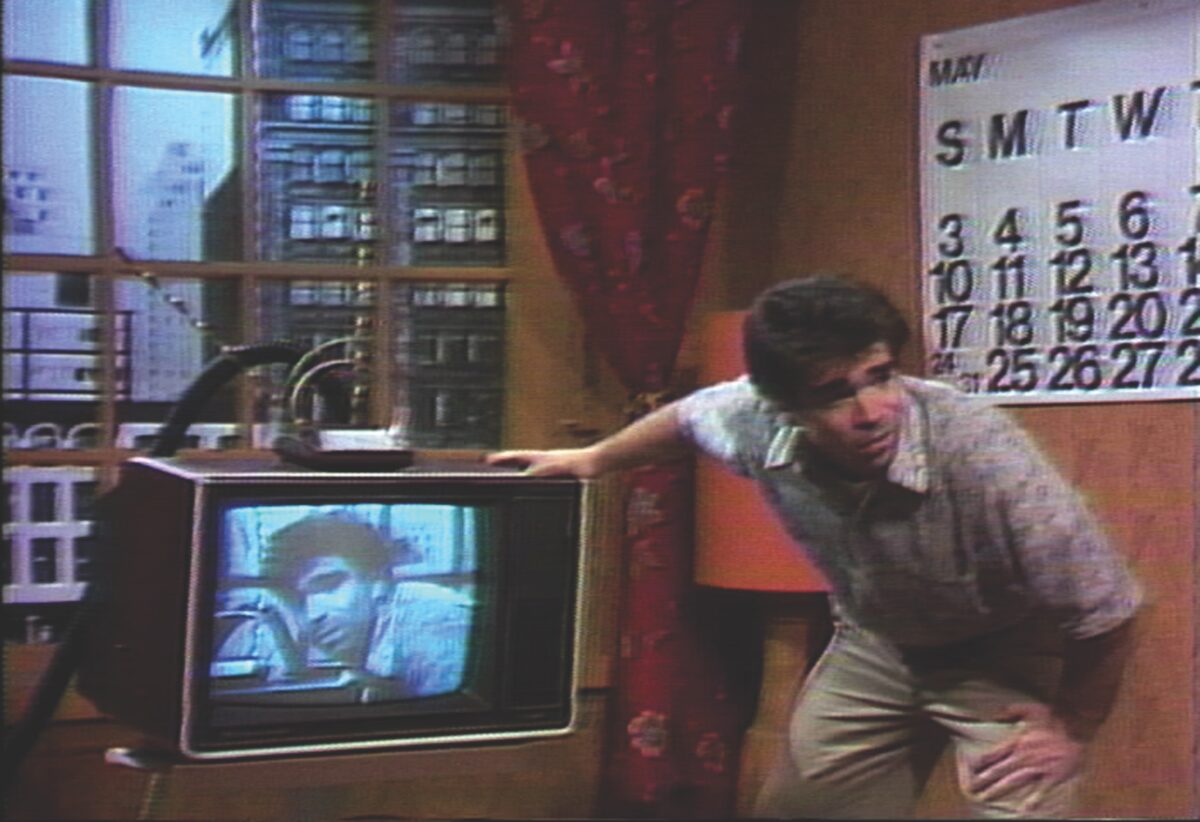

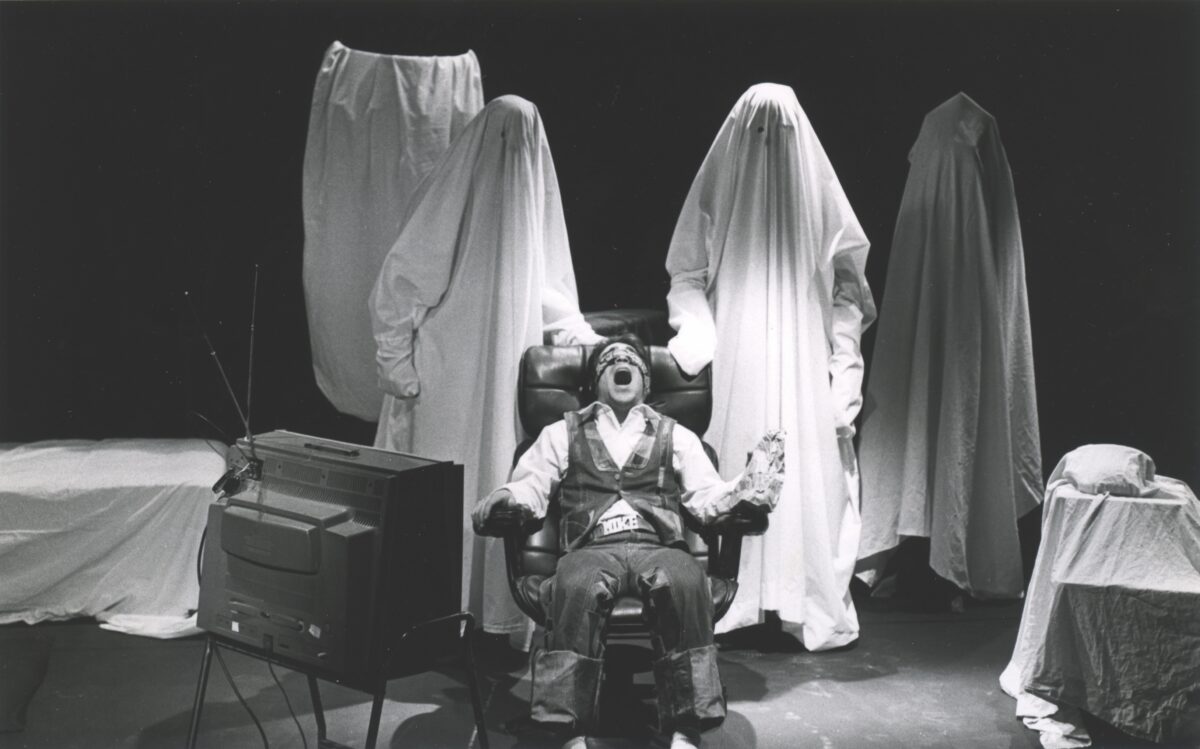

Michael Smith was born in Chicago in 1951, and after he lost interest in painting, he started going to an open mic at a hamburger restaurant. Notes he took there were the germ of his early Chicago performances, like Comedy Routine, where he walks the outline of a stage, empties shaving cream into a tin, and pies himself in the face. “What are you doing, Mike?” asks a voice on tape, and it’s a good question. Smith explored it through early, prop-heavy performances, and in the ’80s he fleshed out the character of Mike in gem after gem of collaborative video. There’s It Starts at Home, in which Mike gets his own reality show; and Secret Horror, in which unexpected ghosts show up for a come-as-you-are party after Mike wakes in terror one night to the sudden appearance of an ugly new drop ceiling in his home.

Mike isn’t Michael Smith; or, put another way, Smith is the artist, and Mike, the art. He’s the protagonist of many of Smith’s videos and performances, an everyman with a lineage in the work of Buster Keaton and Jacques Tati. Sitting in his living room that night, I couldn’t help but feel like I was sitting among objects charged with potential. The space had the energy of a set. Everything was ready to use. There was the kitchen table where he ate, the broom, a window. At some point I got up to use the toilet.

Smith gave me an eight-DVD survey of his work and said that the record label Drag City, in collaboration with the publisher ARTPIX, planned to release a box set next year on Jim O’Rourke’s imprint, Moikai. The more of the DVDs I watched, the more my memories of that night began to blur with the work. The patterned armchair where I’d sat—wasn’t it like the one where Mike sat in his first video, Down in the Rec Room? And when I flushed the toilet: that was familiar. When Smith took me to MoMA to see his installation Government Approved Home Fallout Shelter Snack Bar, a sculptural display that perfectly recapitulated the set from his ’80s video of the same name, there was a moment when I saw Michael Smith standing by the shelter’s bar, while, on the television in front of us, Mike, wearing a shirt with his name stitched on the collar, poured himself a cup of coffee. “Coffee,” he said. “A meal in itself.” I’d heard this before, hadn’t I? On an arcade console nearby, a pixelated Mike blinked on and off. “I hope he’s drinking decaf,” said a woman on the television. “That’s a lot of coffee,” said another. I’d argue it’s this repetition of and estrangement from an intentional, small vocabulary of objects—which came out of an early, insistent interest in minimalism—that begins the growth of something crucial connecting all of Michael Smith’s art. A whole world.

The work on the DVDs ranges from the earliest performances of Baby Ikki—or the Baby, as Smith will call Ikki in conversation—to puppet shows with Doug Skinner and collaborations with William Wegman, Seth Price, Mike Kelley, Joshua White, and many others. There is documentation from shows he exhibited at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Museo Jumex. This interview took place in Smith’s studio in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, about eighteen months after we first met. We sat together at a metal table, drinking coffee.

—Hayden Bennett

I. The Coffee

MICHAEL SMITH: Thanks so much for the coffee.

THE BELIEVER: Have you ever been to Qahwah House, this place?

MS: That Yemeni place around the corner? I have. It’s so popular.

BLVR: Yeah.

MS: Somebody who visited, they picked up a coffee from the same place. And then I picked one up. It’s quite strong, which I appreciate.

BLVR: Can you talk a bit about the genesis of Mike? The character.

MS: I would always refer to myself as Mike because most people call me Michael. Mike just sounded funny. My brother would say, “Hey, Mike.” It was this kind of diminutive way of talking to myself. I don’t know about belittling; it was just, different—familiar or something.

BLVR: Estrangement through that familiarity, maybe. Do you remember when Mike started asking himself, “I wonder what I’m going to do today?” It’s a question that often drives his narrative.

MS: A lot of the character came from the voice [speaking slowly], “Hmm, I wonder what I’ll do.” And then it’s pretty flat-footed. He checks his list. Or he makes his list. Maybe it gives a sense that he’s got some free time.

BLVR: Yeah, every morning there is a new to-do list. There’s more coffee. It got me thinking a lot about repetition. Repetition with Mike never really gets old. It’s hopeful, like something’s coming.

MS: I think that has to do with my process. I sit down; I wonder, What am I going to write about today?

BLVR: There’s no real anxiety for him.

MS: No, that’s the thing I have respect for about Mike. He doesn’t get anxious like me. I mean, he gets baffled. Flummoxed and stuff. Maybe the Baby expresses more of that.

BLVR: Oh, totally. You’re very nice to Mike, how you set him up.

MS: Probably indirectly, it’s me being nice to myself, which is good to see. Sometimes I don’t know how to do that.

BLVR: There’s an openness, too, that got me wondering whether the Quaker meetings you used to go to had a lasting influence.

MS: At the time they did. I was really young.

BLVR: How old?

MS: I went to college when I was seventeen, and then I started going to meetings. A friend of mine, a professor—we became friendly. He went to Quaker meetings. It was also a way to establish a stance against the war. I actually went to them in New York.

BLVR: Conscientious objection for Vietnam, yeah. The way Mike is—it feels like there’s something about Friends meetings and the idea of presence with one another.

MS: I appreciate that connection. But I never emptied my head, really. I never thought about it. It’s possible there was a connection, because I was more open then, but I wasn’t a very spiritual guy. Neither is Mike.

BLVR: Receptiveness is what’s crucial to him; that’s what I’m thinking about.

MS: I mean, he is kind of a sponge—he takes in and there’s not much he gives out. Unfortunately, I think I’m finding that the overlap between me and him is getting more and more apparent.

BLVR: What is?

MS: Oh, the distance between us is really tightening up as I get older. I’m slowing down. We’re meeting together, and physically, I feel very close to him. A lot of his themes now relate to my own physical aging. That’s becoming the subject matter.

BLVR: It used to feel like there was a gap?

MS: Yeah. Before, I had a sense of Mike as a younger person who was invisible. That’s what it is. I’m an older person now and I understand this idea of invisibility, which happens as you get older. Mike was kind of invisible before I was. We’re catching up to each other.

BLVR: In the early performances, after you stopped painting, you were thinking about Nixon’s silent majority and a character who was as bland as possible—Blandman.

MS: I wrote to ask a lot of people who Blandman was. It was mostly foods that I got back—doughy, bland foods.

BLVR: Blandman sort of became Mike, right? You said that before your first video, Down in the Rec Room, Mike was basically a hat rack for props.

MS: Yeah, he was a plinth to hold stuff. I was trying to flesh out his character with props.

BLVR: What changed?

MS: I had a place for him. With Rec Room I came upon a beginning and an ending. Like, Oh, he’s gonna have a party? Oh, the party is not happening? I was trying to deal with an arc that gets deflated completely. Even though the set was very minimal—it’s a really impoverished set—it suggested a certain place in society, a standing. That’s how I figured out Mike. I was approximating him, and the more I worked with him, the more certain themes presented themselves and it made sense for him to go up against those themes.

BLVR: There is a funny permanence to what’s on the set—the armchair, the mailbox, the television. They all get used, and more than once. I’m thinking about how often Mike goes up against an external voice, telling him what to do. The tape machine, the television. There’s often a voice that’s almost goading him.

MS: Richard Foreman was a big influence.

BLVR: Is he funny?

MS: Some people may not find his stuff funny, but when I first saw him, I found it hilarious.

BLVR: That voice on the tape evolves into characters who call the shots for Mike, at least in the ’80s videos. One of my favorites is this little hairpiece in It Starts at Home. He’s a producer who gets Mike onto TV, something like a reality show before there was such a thing. He’s an authoritative hairpiece in a chair, surrounded by cigar smoke. Proto-Steinbrenner from Seinfeld.

MS: That was very strange. That was something my mother made for her cat.

BLVR: I didn’t know that. Oh my god.

MS: Yeah, no, she made that little mink thing. I think it was something she had left over from a coat or something. And it was a little toy. She was a seamstress. And she said, “You can have it.”

BLVR: That’s so funny. Eric Bogosian did the voice?

MS: Eric did a really good voice for him. There was some very good dialogue written. I mean, there were many more people working on it than me.

BLVR: It was a nice thing about getting to watch the DVDs—seeing names and thinking, Oh yeah, they were all hanging out. Did Bogosian write the dialogue?

MS: No, a lot of it was written by Dike Blair and Barbara Kruger.

BLVR: I remember one name surprised me.

MS: Maybe Randy Cohen? He was the original ethicist. He was part of my group of friends. A bunch of my friends got together and did that. Eric Fischl, Barbara Bloom, Carole Ann Klonarides.

BLVR: Your friend group was generative for Mike.

MS: I’m very happy you were able to watch the DVDs.

BLVR: It’s rare to have such an accessible record of performance art—there’s a whole world in there.

MS: Yeah. I learned from the people I worked with. Especially in terms of making or inhabiting a set. For It Starts at Home, I worked with the painter Power Boothe. For the Fallout Shelter installation at MoMA, I worked with the artist, now poet, Alan Herman. He was a total pro. He had done Super Bowl commercials. I picked up a certain sensibility. Mike is always missing it a little. That also relates to me. I’m constantly a little behind.

BLVR: I mean, there can be a sadness when Mike fully accomplishes a task, or fills out the to-do list. I’m thinking of Portal Excursion, when he learns two words out of the dictionary every day. After he’s learned the words, there’s this sense of exhaustion.

MS: I take it to the absurd, but that was a true story about my uncle. He told me to pick two words every day from the dictionary.

BLVR: Did you?

MS: No.

BLVR: [Laughs] The way Mike describes the project, there’s real wonder in it. Two new words.

MS: He takes pleasure in those small things. Excuse me, may I use the restroom? I’m asking your permission.

II. Mike the Wipe

BLVR: Did you have a lot of free time when you were making those videos?

MS: I did have free time. I always lived very frugally, and I had a little money, so I was here, working, doing my work. Performing.

BLVR: You were working other jobs?

MS: I was. Let’s see now: I helped somebody do a little paste-up for a couple days. I became a professional house cleaner for several people: Mike the Wipe.

BLVR: [Laughing] That’s what you went by?

MS: Just jokingly. I worked a couple days a week. I had a storefront. I paid $175 a month in rent, and I could afford it. It was on Spring Street and Elizabeth. I had that studio for, I don’t know, fifteen or seventeen years, and then they moved me next door.

I remember going by after I left. They were renovating, and they took down the walls, the outside walls. I walked by and I looked. I said, “Huh, there’s my toilet.”

BLVR: Was there ever a question of whether you’d leave the art world?

MS: When I was doing those variety shows, those talent shows—I didn’t leave it, but I was more focused on that commercial world. Now I’m uninterested in both. [Laughter]

BLVR: You started the talent shows in the mid-’80s?

MS: Yeah, in the East Village. This fellow Steve Paul—he saw a show and got very interested in working with me. He was sort of an impresario. He had a very well-known club in the late ’60s called the Scene. Steve Paul’s the Scene. He managed the Winter Brothers, David Johansen, Tiny Tim. His boyfriend was an artist, and we were both peripherally in this circle of people. Steve had his own label called Blue Sky. He approached me and said, “I’d like to manage you.” We became coproducers of the Talent Show. He had access to people like Fran Lebowitz. I got really caught up with that for about four years.

BLVR: You were trying to pitch the show to networks.

MS: He was doing that, yeah. I had a manager, and then I got an agent from a big comedy agency. I remember being welcomed into the fold by this one guy named Roger Vorce. He was the personal agent for Liberace. I got to see Lee’s last show at Radio City.

BLVR: Did you ever go to Hollywood?

MS: I did go to LA, and at one point, after the talent show didn’t get picked up, I remember trying to do a kiddie show. That was, like, after Pee-wee, you know, trying to piggyback on Pee-wee.

BLVR: Was he an influence?

MS: I remember going to his stage show in the late ’80s at Carolines. And then I started doing a regular show there. For a while it was kind of exciting. I was dealing with all these comics. It’s amazing who went through my show. Kids in the Hall’s first live act.

BLVR: Did that grow into your HBO Special [that aired on Cinemax]?

MS: Yeah, it was really funny. They saw the show and said, “You need a famous cohost.” We spent a year going for a visual discrepancy—we approached Schwarzenegger, Danny DeVito, Cyndi Lauper. Different people. Most of them came back with “Who’s Mike?”

BLVR: Did you talk to any of them?

MS: My partner, Steve—he was more in that world than I was.

BLVR: The executives liked you?

MS: Yeah, the executive who was curious, who said, “Go ahead and find a famous cohost” before seeing the show. And then they came to the Bottom Line in the Village, saw a show, and said, “Oh, Mike’s OK. We like Mike. Deliver this in six weeks.” Then we had to do it.

BLVR: Did you enjoy doing the talent shows?

MS: They were so much work. I was a producer. I was a stage manager, schlepping that shit all over the place. I did enjoy it. But I didn’t make any money.

BLVR: You weren’t living off it.

MS: Living off it? Oh no. I lived off grants for many years. Fellowships and grants. I think it was around ’92 when I realized the ’80s were over and I was broke. That’s when I started to do manual labor, working for friends, house painting.

BLVR: The ’80s do seem like a different time as far as fellowships and grants and anything where federal funding’s concerned.

MS: I sort of deceived myself then, thinking I was busy. I just kept going forward. I lived modestly.

BLVR: Did you like the odd jobs you were doing?

MS: Not at all.

BLVR: How’d you find them?

MS: I put an ad in the Times to clean and to cook for people.

BLVR: That was Mike the Wipe?

MS: No, that was Mr. Smith.

BLVR: Do you still have the ad? I guess the Times probably archived it.

MS: I mean, it’d be very tiny. I just said, “Will clean or clean and cook.” I’m not a bad cook. But I said, Oh, I’ll try this. I think I got one call. It was this person saying, in a breathy voice, “Do you do windows?” And I said, “Yeah, if they’re dirty I’ll do them.” And she said, “Do you need rubber gloves?” I said, “Well, I don’t really use rubber gloves.” And she said, “Will you do ovens?” And I said, “You know, yeah, if you—” and she said, “Do you need rubber gloves?” Everything was about rubber gloves. [Laughter]

They finally gave me the address, and I went. There was no one there. A total waste of my time.

BLVR: A prank?

MS: A prank, or just getting off on talking to me. Mostly I cleaned for people. Some of them gave me their keys. I cleaned for this guy who had a torture chamber in his house. That was interesting. Another person—this guy in the West Village—had all these things in capsules. They looked like those packets to preserve foodstuff or something. They were poppers. I would pull them together and put them in a dish. He thought that was so cute. I didn’t know. I didn’t do poppers.

BLVR: Did you cook for anyone?

MS: No, no one wanted me. They just wanted my cleaning. I basically have no skills. So it was hard.

BLVR: Organizing’s a skill.

MS: Yeah, but I can’t even do that. For others, I couldn’t do that.

III. Milk It

BLVR: There’s this one early interview you did about Baby Ikki. You’ve since expressed that you were pushing back because you hadn’t really analyzed the Baby.

MS: That was in one of the first issues of BOMB, I believe.

BLVR: Yeah, yeah. I was wondering if being closed off about the Baby served you. Or if not talking about Baby Ikki was an advantage.

MS: Right, well, I wasn’t really keeping up with the readings everybody was doing. I had done therapy, but I wasn’t going that deep with the Baby. People would mention infantilism and stuff like that and I would kind of go, “Huh.” I’m a repressed guy. I didn’t even want to acknowledge that until I collaborated with Seth Price. We looked at infantilism sites to get certain ideas. When I started out, they were having adult babies on these talk shows and stuff. Now there is this thing with Trump supporters wearing—what is that with the diapers?

BLVR: I don’t know.

MS: Yeah, there are some people in diapers supporting Trump. I have to look into that. It’s always odd for me when people go, “Oh, you’re the Baby guy.” I do it well, but you know, it’s an odd thing.

BLVR: I can see how it’s purposefully not verbal.

MS: I don’t do a lot of thinking for the Baby. There’s really no conceptual approach.

BLVR: You can’t really see in those sunglasses, can you?

MS: I can see.

BLVR: OK, you can see.

MS: I mean, the sunglasses are great because they cut me off in a way. They’re a little ridiculous and undersized for my head. They really press up against my eyes and it sort of completes the mask and creates a space for me. I have to look forward in them—they’re like blinders—and I’m not so aware of peripheral stuff. Babies get distracted really easily.

BLVR: Distracted by what?

MS: What’s in front of me, usually. A noise or, I don’t know, a child. Something shiny. If I sense a certain kind of, like, discomfort or vulnerability, I’ll go to that person. I’ll just push it a little, you know, but I’ll never purposely make someone totally uncomfortable. I’ll go close to that.

BLVR: The Baby’s also got a sense of wonder.

MS: He gets preoccupied with nothing. There’s times when he’s just playing with a feather. Or a little speck on his finger. He’ll spend a minute looking at it and nothing’s happening except the sharp focus. People are wondering what I’m looking at—or they see what I’m looking at and it’s, you know, a feather. It’s very dumb.

BLVR: What’s it like to embody him?

MS: It’s a very physical experience. Because I get double-jointed. [He demonstrates with his hands.] Stiffness. Some people who knew me found it really uncomfortable. I remember going out with some people and I’d be doing the Baby and they were just…

BLVR: People you were dating?

MS: Yeah. My sister was very uncomfortable. She was an occupational therapist, but it made her uncomfortable. That’s where the sunglasses come in handy.

BLVR: It’s hard to separate somebody from their character sometimes.

MS: Yeah, when people don’t know you. When people do know me and see the Baby, they just wonder, Why?

BLVR: What was it like coming up with him?

MS: I remember I had invited people to my studio. I just had this idea. I had no idea what the Baby would do, or how it would move. I got onto the floor and started moving.

BLVR: That’s the first one, the performance on the DVD. It felt like he wanted to understand why he was there, asking, “Why do people have babies?” Writing his name on the blackboard, “Ikki.”

MS: That’s the process I went through when I was coming up with the character. All these friends of mine were really deeply involved with feminism and support groups. And I thought, Hmm, “gender.”

BLVR: The baby doesn’t often go in for excess. I guess there’s that part of The Dirty Show when [the performance artist] Brian Routh comes onstage and pours food into his mouth. People have expressed that Ikki can make them feel a real motherly concern, and when Routh pours the mashed-up food into your mouth, that was a moment when I really thought, Oh god, don’t do that to a baby.

MS: That was so uncomfortable for me. I don’t usually bring the Baby to such dark places. And also, he was talking about Nazis and stuff. That was really uncomfortable for me, being Jewish. It was just weird. But I like it in relationship to the other stuff.

BLVR: Well, he tied you up. You couldn’t speak.

MS: There was a certain sadism. It was kind of curious. He was married to Karen Finley. I could hear her cackling in the background.

BLVR: I know Mike Kelley also wanted to go the darker route when you brought Baby Ikki to Burning Man.

MS: He was interested in seeing something a little more abject. There was that one woman who whispered in my ear. “I feel like I’m lactating,” or something like that. I followed her into her tent. I had no idea what I was doing. I have a feeling she was wondering what I was doing. The Baby checks in and checks out immediately. He sort of tests the water and then leaves. I sort of posit this possibility but don’t really let it develop that much, I guess.

BLVR: I think there’s an innocence to the Baby. There’s a relationship to Mike in that.

MS: The Baby’s very forward, and Mike’s fairly passive.

BLVR: And they’ve both got your eyebrows. That’s a feature you know how to milk.

MS: Ad nauseam.

BLVR: That’s kind of my question: How do you know when to stop? It’s very tight in the videos.

MS: That’s where editing comes in. Our shooting ratio was so out of control. I got good at that. Also, when you’re not talking, you know. Mark Fischer focused on it. We noticed it.

BLVR: When you have a shtick that works, how do you stop it from running into the ground?

MS: It’s touchy. When you identify a shtick, you kind of back away: Oh boy, is he stale. Boy, is that stale. At one point you see somebody do a lot of the same thing and call them a hack. And then I thought, How do you become a hack? At least hacks make a living.

IV. Strike a Claim

BLVR: There’s that interview you did with Mike Kelley that ends with him mentioning how your work is ahead of the culture sometimes, like with Beavis and Butt-Head or The Truman Show. At the end of that interview he was like, “Why not claim it? Everybody else does.”

MS: What did I say?

BLVR: The interview ends.

MS: I don’t want to be held accountable. Things are in the air. Maybe I felt that I did what I did, and I carved out a little place for myself. And I’m between the cracks, you know?

BLVR: The idea of “claiming” something is just odd. Some artists, that’s what they’re really interested in, it feels like. Where their focus is.

MS: I have an ego. I mean, if the writer wants to do that, fine. But I don’t find that very modest, you know, claiming your turf or whatever?

BLVR: It’s not modest, no. It’s a false idea of what working creatively is, right?

MS: I think also, as my father would say, “That and $2.75 will get me on the bus.” [Laughter]

BLVR: It’s not an ego thing, really, but where did the mike belt buckle come from? It is his name…

MS: Canal Street. I walked by Canal Street, I saw it, and I thought, Oh, yeah, maybe I should get that.

BLVR: And people gave you MIKE clothing.

MS: People did eventually, yeah. Little things. Now people don’t give me that stuff. I don’t gravitate toward this MIKE stuff. It actually makes me a little uncomfortable. I have a few things. I belonged to this club called Mikes of America. But now I’m all about rainbows.

BLVR: When did that start?

MS: I lived in this incredibly depressing place. It was like a converted garage, like a shack. One friend of mine who stayed there, he called it the Unabomber’s Cabin. It was when I was going back and forth to Texas to teach, and I didn’t do a lot of decorating, let’s say. I had a bed and a table and then a kitchen. I mean, it was minimal. I had a chair that I sat in.

At one point, I thought, It’s a little depressing in here, and I was at a thrift store—because I did a lot of my propping at thrift stores—and I saw this very kitschy rainbow. I mean, a really stupid, poofy one. I thought, kind of ironically, I need a little color in my life. So I bought it, and I put it up. And then I bought another one. And then I thought, Yeah, I need a little color, maybe a little hope. Next thing you know, people started giving them to me.

BLVR: The selective accumulation is interesting. It makes me think of some other projects you’ve done: drawing credit cards, collecting bags from hospital visits. You were drawing open zippers for a while.

MS: The rainbows and unicorns, I think they’re going to yield something. I don’t know when, but I think they’ll yield something.

BLVR: I was thinking that cataloging is maybe like tidying. You do like a tidy space.

MS: I do, yeah. The studio is even kind of messy now, but my house is, yeah, tidier. You’ve been.

BLVR: It was striking how it felt—not like Mike’s house, exactly, but it had that energy to it. Like a set.

MS: I like to sweep. I even have a good vacuum, but I prefer sweeping.

BLVR: Watching the DVDs in order, it’s really interesting to see Mike go from being in the home, getting the mail, figuring out what errands to do, to dealing with colonialism and other globalized systems.

MS: It’s probably me responding to a particular social thrust or a certain context. You know, I’m presented with a context, and I respond to it.

BLVR: Your idea for the International Trade and Enrichment Association came about that way, right? You’re responding to these global systems—Mike as the colonizer. It came out of reading Heart of Darkness for a group show, right?

MS: Yeah, I read it for that. Dense. Really dense. I was expecting, Oh, this is going to be, you know, a breeze. It was like reading Ulysses or something.

BLVR: You put Mike in the new context.

MS: That’s probably when my life influenced Mike more. That came out of a period, in ’94 or ’95, when I could not get fucking arrested. I started to respond to this business of art. The hyping up of the professionalism of art or something.

BLVR: Interstitial, a collaboration you did with Joshua White, is similar. I really have no idea what any of the artists Mike is interviewing are saying. Even the premise: “The place between two places where ideas and dialogue and opinions come together, intersect, or overlap”—I mean, I guess it means something. The editing is kind of jaw-dropping. I love Interstitial. Riffing off public access stylistically like that really picked up later, but how directly influential Interstitial was to comedy, I don’t know. It feels very ahead of its time.

MS: I don’t know how many people saw it, yeah. I think it’s that deadpan humor. It was sort of in the air. I mean, you know, I come from Chicago; there was Bob Newhart, and then there was that stuff in the in the ’70s that was purposely flat, Andy Kaufman and Steve Martin. Jackie Vernon’s delivery was very influential for me.

BLVR: Doug and Mike’s Adult Entertainment also has some perfect art-world satire. There’s this puppet gallery show in the basement of a Blimpie. I think about it all the time. The cheese log.

MS: Thank you for mentioning the cheese log.

BLVR: They had a show called Reconsidering Context?

MS: Yeah, I made that up.

BLVR: I ask because I kept thinking—both that and interstitial, they’re sort of nothing puff words, but they have a real relationship to your work. You do recontextualize the to-do list, the rec room.

MS: Oh, Reconsidering Context was for Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Museum in Progress. The DO IT piece How to Curate Your Own Group Exhibition. That was a little prescient in terms of, you know—I think I recently heard somebody talking about being a content provider. I had that line in that piece: “Artists are content providers of the future.”

BLVR: Do you feel like artists are the content providers of now?

MS: I don’t know. I don’t give a shit. [Laughter] Whatever. They do add to it.

V. “In my ear and out my ear”

BLVR: I can see where any one culture can get to feel small—especially when it’s so professionalized. The first novel that I wrote was an art-world satire. Notes came back from editors that were just like, “People don’t care about the New York art world.”

MS: You didn’t have enough drugs in it?

BLVR: Not really. It was what I found funny. At the time I figured everybody was interested in Donald Judd’s son.

MS: [Laughter] Flavin?

BLVR: His name did a lot for me.

MS: Have you been to Marfa?

BLVR: I haven’t, no.

MS: Judd’s time-out room stuck in my head. He had a room with a window, a small room. A lot of books in there, where he would go not to be bothered. You could see him. I think you could see the back of his head. It was a small room, near his library. I remember I thought, It’s really odd.

I remember walking through the courtyard with these high walls around it separating it from the town. And I was there with Dan Graham, and out of nowhere he starts talking about the Branch Davidians. I thought that was so perfect. David Koresh. That was very funny.

BLVR: I’ve been to Judd’s house in New York.

MS: I used to pass that a lot because I lived down the block on Spring Street. One of those bad galleries was across the street, you know, with flowers and things like that. Because it was so bright at night, it would reflect onto Judd’s windows. You could see these shitty paintings in his windows.

BLVR: For whatever reason, his art really mystified me as a kid. Art in general—my parents took me to museums and we’d never really talk about it. You’ve mentioned a similar experience with your parents: seeing theater and not talking about it.

MS: Or my mother, her comment would be “That was interesting.”

BLVR: Right. My mom said that too: “That was weird.”

MS: They took me to some curious productions.

BLVR: Genet, right?

MS: Yeah, was it The Maids? The Blacks, maybe? Wasn’t there one called The Maids?

BLVR: There’s both, yeah.

MS: They took me to The Maids. And some Living Theatre productions. The Brig. That was so interesting.

BLVR: How old were you?

MS: Probably twelve or thirteen. That really stuck in my head. That was totally real life. In fact, I show my students that video.

BLVR: There’s a lot of screaming.

MS: I was just, like, struck by it, baffled by it. I mean, not a lot happened, but it was an assault, you know? I didn’t know where to put it.

BLVR: What TV do you like?

MS: Well, I think TV informed my thinking. I don’t necessarily like it now. I mean, I just go into a stupor when I watch this stuff. The algorithm, you know: You like this shit. How about this shit?

BLVR: What about Storage Wars?

MS: I binge-watched it. I was intrigued. Then they started to develop these different characters and I lost interest. And then they would do it in different places, almost like these chef shows or something. I don’t give a shit.

BLVR: You were in it for the lockers?

MS: They were opening up these lockers just filled with shit. They don’t address the fact that, a lot of the time, these are people’s lives. Why they left them there, they don’t even address that. It’s all about the ridiculousness, the way the price adds up. I know about that stuff. It’s worth shit, most of it.

BLVR: Yeah, every time they see an instrument case: “I hope this is a Stradivarius.”

MS: Right, right, right. I used to look at garbage sometimes. At one point, uptown, I found some really good stuff. I found a small gay porn collection—I must have made a good five thousand dollars from it. This was many years ago. I kept one piece. Probably it’s worth a lot more now.

BLVR: In the past, you’ve talked about the freedom you feel with the drawings you do, right? A lot of them are plans for performances. And then those performances can become videos, and those can become sculptural installations. An idea occurs. You make it work.

MS: I should follow those more. Trust myself a little bit more sometimes with those drawings.

BLVR: Yeah, I guess I have the advantage of seeing the work once it’s done—and all at once. When I look at the drawings together, their logic makes sense to me. That’s what I was talking about, something in the interstices. The movement between forms feels significant. Where the freedom’s concerned, you feel like you’re stopping yourself?

MS: Oh yeah. Do I trust myself? No.

BLVR: Thinking too much will make you stop?

MS: Yeah: Does this make any sense? This is dumb. Or: I’m insecure.

BLVR: How do you push past the insecurities?

MS: A lot of times I forget. Or I distract myself with something else. Deadlines help too. I don’t know if I get insecure now; I just need to move on. By sort of daydreaming. You write—you’re familiar.

BLVR: The appealing thing is the daydreaming.

MS: God, I can do that. I’m so good at that.

BLVR: I guess there’s a reason Proust wanted to be in a cork-lined room, in bed.

MS: When you started talking about those Friends meetings before: maybe that’s what I’ve noticed. More and more I’m just looking out with my coffee, listening to the radio, but it’s kind of going in my ear and out my ear.

BLVR: What station?

MS: I’ve got one of those radios that NPR gives you. It’s fixed on one station, but I’ve never gotten it to work. Maybe because I’ve never had fresh batteries in it. It comes on strong and then it shuts down. I’m just looking at it. It becomes an object to look at. And then I turn it on again and it goes on for, like, twenty seconds, and then it goes off again. A lot of times with podcasts, I’ll be listening and the next thing I know, I don’t remember anything. I have to rewind it. It’s mostly an activity of rewinding.

BLVR: I’m remembering it now, in your kitchen. It’s a WNYC radio?

MS: Yeah, yeah. I’ve got to get some new batteries. I’m going to do that tomorrow.