Mierle Laderman Ukeles penned her Manifesto for Maintenance Art overnight, in a cold fury. It was 1969; she had given birth to her first child the year before. Ukeles no longer knew how to respond to the question, regularly asked by other artists, of what she was “working on.” Constantly occupied with tasks, she had no obvious product to corroborate her labor (a clean kitchen? a robust baby?), so in a singularly radical gesture, Ukeles invented “Maintenance Art.” In doing so, she posed entirely new questions about art. What if taking out the dirty diapers and washing the dishes were themselves considered serious and meaningful work? What if boredom and repetition were content worthy of exploration? What if we understood sanitation work—much like housewifery—as being virtuosic, skilled, and full of its own distinct choreography? What if the most interesting work to be made had no tangible results, and were about keeping other people alive?

Ukeles has been making work for almost fifty years. She washed the steps of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, photographed pregnant women cleaning chickens, and shook the hand of every maintenance worker in New York City. Over the length of her career, she has created installations and performances that contend with rehearsal, repetition, invisibility, perpetuation, and productive undoing, all strategies that might be considered “practice” within current art jargon.

Two years ago, I began working on an experimental book about artists’ relationships to the word practice. As I outlined and drafted, threw away whole chapters, and reinvented my own premise, I kept returning to Ukeles. In an emboldened moment, I reached out to her, a stranger, asking if she would speak about her work in relationship to this often-overused term within the art world. Her retrospective Maintenance Art had recently opened at the Queens Museum, and her book Seven Work Ballets had just been released. Despite being extraordinarily busy, Ukeles said yes.

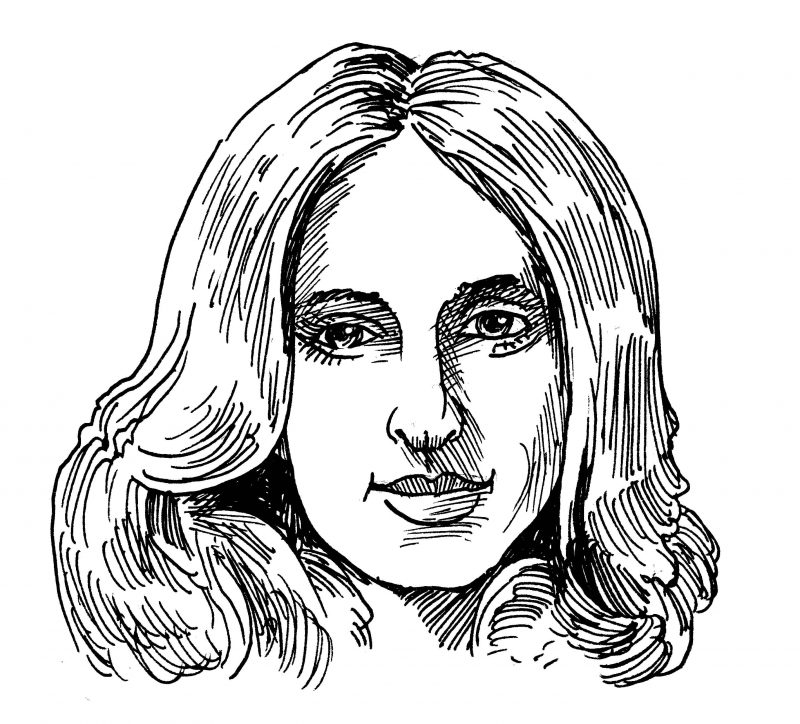

—Carmen Winant

THE BELIEVER: Nearly every artist I know uses the term practice to describe the thing they do. The word seems to constitute everything: research, process, presentation. Do you like the word? Or use it in your own life?

Mierle Laderman Ukeles: No. I never use it. It gives me the creeps.

BLVR: When did you first encounter the term as an artist?

MLU: I can be very specific about this. In 1980, I was invited to be in an exhibition in London curated by Lucy Lippard at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. Six months earlier, I had completed the performance work Touch Sanitation; it was an eleven-month performance that occurred all over New York City. I was just emerging after a year and a half of researching of immersive learning about the sanitation system and sanitation workers in the city. Lucy’s was one of the first international exhibitions of feminist artists, and I made a rather large installation for it. Across the gallery from me was Suzanne Lacy. I had never met her before, and that was the beginning of a wonderful and very long friendship. Along with Jenny Holzer and a few others, Suzanne and I were two American artists among many European feminist artists. The thing that struck me the most was that they all spoke about their “practice.” I found it rather shocking. I had never heard the term before, applied in this way.

BLVR: Shocking? Why?

MLU: It made them sound like they were wannabe doctors. Artists don’t need that kind of professional certification or accreditation. Architects and lawyers need a kind of license, not artists. And on purpose! We are who we are; this is how we assert our freedom. Using that word… it felt like an effort to validate themselves.

BLVR: Why do you think the term caught on for European artists first? And European feminist artists at that?

MLU: Those European artists, they were linked to a tradition of theory. I felt so different from them; for me, and maybe for American artists and feminists at that time, art was a huge open field of action. I felt these European feminists—who had really revolutionized and defined themselves in opposition to conventional, patriarchal power structures—had dragged with them a kind of obedience in this way. Or at least an adherence to a structural criticism and theory. The use of the word practice demonstrated this link to a prior order.

BLVR: What does the term practice summon up in you?

MLU: Well, what are you practicing, exactly? I used to have to practice the piano. My mother worked hard in order for me to go to the best piano teacher in Denver, growing up. She drove me across town every week. I had perfect pitch and I loved music. But I didn’t practice. My mother had to sit with me to see that I wouldn’t sneak away. I loved music—I loved listening to it; so did my whole family—but practice summons in me a shudder reflex. I became an artist to be free! Or, at least, to pursue freedom. Doesn’t practice withhold that?

BLVR: How do you account for the embrace of the term practice here in the States?

MLU: It has caught up with us. Practice is coming from the huge, rolling academic system of arts programs, BFAs, MFAs. Huge numbers of artists feel they have to get an advanced degree to get a job and make a living. The competition is so dense; the numbers have swollen—it is, unfortunately, an understandable desire and need. Institutions insist that artists have these degrees in order to be hired. Practice becomes a natural part of adhering to academic structures, a way to be legitimatized within its framework. It’s an attempt to create a common language between different fields within the university, to be taken seriously by other intellectual professionals. Do you agree?

BLVR: I approach practice from a very different, slightly unusual perspective. For ten years I was a competitive long-distance runner, so for me practice is the site of the body and its training rituals.

MLU: When you give the word practice a valence from the world of athletics, it shifts. It actually becomes way more interesting. The work of art is never separated from the artist working on him- or herself. This is the task of any living artist who takes risks and is really in it.

BLVR: Right. As an athlete, I loathed performance—that is, competition—but really loved practice. It allowed me to feel my own body. It was the place I could court exhaustion and fatigue. There was real pleasure in the repetitiveness.

MLU: This sounds like the practice of an artist, if there ever was one.

BLVR: And in many ways, as I am now learning, the practice of a mother.

MLU: Yes. Working to your limits, accepting levels of boredom.

BLVR: Your work is particularly difficult to describe in that it is productive but leaves no results. In fact—as so much of it deals with cleaning, tending to, and service labor—often there is less there than when you began. If you don’t call it a practice, how do you describe it?

MLU: Let me tell you a story that may do the work of answering that question for me. In the late ’60s, I had been doing art about maintenance, with maintenance workers, and about my own maintenance practices as a mother. In 1976, I came to the New York City Department of Sanitation as the artist in residence. I had reached the major leagues of the maintenance world. Walking in there was like walking into heaven. These people are geniuses at operations. They know where everybody lives in the whole city. Think of that. They know how to get there to pick up the garbage of 8 million people efficiently, and without going bankrupt. It was a place where I could deal with pure maintenance.

In 1983, I got invited to be in the first New York City Art Parade, and after a lot of negotiations—a lot, for months—the sanitation department gave me their six best drivers of mechanical sweepers and three days on a training field on Randall’s Island. This is where they have fields laid out like city streets, where the new drivers hone their skills. I had wanted so badly to clear away the traffic, and allow the sanitation workers to be able to show off their skills. This piece, one of my Work Ballets, was a chance at that.

We met in a little wood hut the first day. The six drivers said: “Tell us what you want us to do.” I said to them: “I am not your boss.” I wanted them to assert their power. It became totally silent for a long time. I thought in my head in that moment: Ukeles, you are going to make the biggest ass out of yourself. You have three days! Just tell them what to do. But I kept my mouth shut, and we all sat there without a sound. Keep in mind that these were guys who had officers, foremen, and superintendents above them; they signed off their bodies for an eight-hour workday. But this was not how I understood art to work.

Suddenly, they spoke up. They had fantasies of what they could do with their trucks in this way, how they could use them. For three days, we practiced on those fields. We invented side-to-side movements for a forty-two-block stretch of Madison Avenue. They were amazingly coordinated, unexpected. They did a move called “kissing brooms”; if you aren’t excellent, you can flip each other over. It was perfect; this was our work. This is how I describe it, as a process of collaboration, support, and visibility.

BLVR: If practice, as you know and relate to it, is so heavily associated with top-down, white-collar labor, then of course that word must feel totally remote to you.

MLU: My work is something that plays out in the public—in public institutions, and public spaces. I work in contested zones, not white-cube galleries. Wouldn’t that be nice! I am always in a position of having to ask, to listen to, to meet with, to negotiate. I don’t own these places, like some of the land artists who actually bought the ground they used and built into. Some of them made great art. But they didn’t have to listen, and they sure didn’t have to go to committees. That is what I do: make art that is realized in the public domain. It can be difficult and frustrating. It requires every bit of time and patience. For instance, I am working on a big project at Freshkills Park, formerly the largest municipal landfill in the world. I have been working on it since 1989; it will finally be completed in 2019.

So what is my practice? I don’t know. To survive. To refuse to go away, to engage the support of other people—that is how I describe it. I am going to try, after this conversation, never to use this word again.