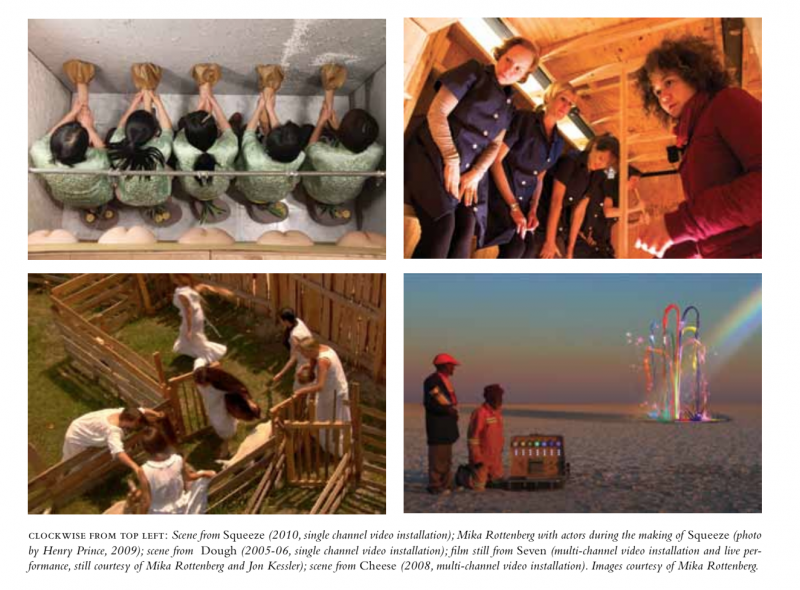

In the wordless film Squeeze by Mika Rottenberg, a factory is abuzz with activity: workers spritz wiggling tongues with water, conduct electricity through meditation, harvest rubber trees, transcend space and time, and endlessly chop heads of lettuce. All this happens, it seems, to produce a cube of worthless, rotting trash.

The product is beside the point, but the process of its creation—the art of its labor—is a phantasmagorical spectacle. Repetitive tasks, the transformation of work into physical objects: these are the elements of Mika Rottenberg’s surreal, industrial films: Mary’s Cherries, Cheese, Tropical Breeze, and the recent performance-film combo Seven. In watching her films, viewers follow strange interlocking chains of logic until, every so often, a magical hiccup allows for a moment of the impossible.

The actors in Rottenberg’s films are laborers. They don’t act, per se, but carry out series of simple, physical tasks. For this reason, she casts individuals who use their bodies as sites of extreme production—bodybuilders, the highly flexible, the very long-haired. Most of her actors are women and her work is often seen through a feminist lens, though its preoccupations are wider than feminist ideology, from Marxism to fetishism.

Rottenberg’s films show in galleries and museums (Bilbao Guggenheim, the Whitney Biennial, Nicole Klagsbrun, Andrea Rosen) but not in theaters, an environment she considers inappropriate for her current work. Often she builds an installation to serve as a viewing room, its atmosphere and structure mirroring the film it houses. Some viewers wander in and out as the projections loop continuously, and others find themselves hypnotized by the artist’s circuitous logic, from beginning to end.

—Ross Simonini

I. BEHIND THE SCENES OF REALITY

THE BELIEVER: For you, what’s the distinction between an art film shown in a gallery and a cinematic film screened in a theater?

MIKA ROTTENBERG: The most immediate thing that comes to mind is the whole ritual of going to the movies. You’re going from the ugly “real world,” and suddenly everything transforms: the carpet is brighter, the lights are brighter, the popcorn machine. You are being prepared to enter a different reality. In the gallery, it’s more straight-up reality; you are not asked to forget about your physical body. In the film theater, you are asked to escape.

BLVR: You often make spaces, little sculptural houses for your films to be seen within the galleries. Is that a form of escape?

MR: They’re video installations—I build my own “mini theaters” for most of my videos. I think about it as taking advantage of the fact I can control the shape and architecture of where my videos are being screened, making the way you experience them a part of the narrative. In contrast to movie theaters, I try to make the viewer more conscious of their own body in space, rather than allowing them to forget where they are. The spaces usually provoke a sense of claustrophobia and slight discomfort. I guess it’s my way of not letting the viewer be completely immersed and escape into the screen, into another reality. In Squeeze, for example, viewers went through a maze-like corridor with a stained, dropped ceiling and gray office carpet—like you are going behind the scenes of reality—then encountered the small black box where the twenty-minute film was projected, but they were a bit disoriented. I wanted to evoke this feeling of going through a portal into another reality, where things seem very familiar yet don’t make much sense. I build these viewing spaces as a way to deal with the problem of the format in galleries.

BLVR: What do you mean by that?

MR: Galleries are not structured to show works with a beginning and an end, so maybe it’s not an ideal place to show time-based work—or maybe it makes artists rethink and reinvent the format. In most cases, the loop makes more sense in that context. It changes the way you edit, and the narrative structure, because an audience can come and go at any time. Although my video installations are not as comfortable as movie theaters, and the technical equipment is not as advanced as in the movies, the sound and the light are very controlled and considered. One thing that’s key for me: the size of the projection. That’s one thing you can control in a gallery situation that you cannot control in movie theaters. It’s a big difference if you see something from twenty feet or five feet, especially when the work is of a more sculptural or visual nature, rather then story-based.

BLVR: Because of the looping and because you can’t expect people to sit and watch the whole thing, you can experiment with pacing a little, whereas cinematic movies always have to keep the viewer’s attention.

MR: Yeah, it’s a challenge for me to keep someone’s attention, not to have them leave. Unlike in a gallery, in a theater it’s a given that people will stay, unless you really bore them—then they’ll walk out. So I try to get someone to stay for the entire loop, but without forcing them to stay. One main reason I like the format of the loop and exhibiting the work in a gallery is that my work is more based on space than on time. So for me, I think the key thing is that it’s more like you’re witnessing a space, an architectural structure. In “classic” films, you’re revealing the narrative through behavior in time. I think I’m revealing the narrative through space, rather than a story line. The story is about the space or about materials and not about, say, an emotional drama.

BLVR: Could another word for the space be sculpture? Because it seems like some of these film sets are sculpture.

MR: Absolutely. It’s not just that the sets are sculptural, the motivation is sculptural.

BLVR: And why do you think film is the way to show the sculptures, as opposed to a photograph or an installation?

MR: These spaces can’t exist in reality. I use film as one of the architectural ingredients. So I use editing as a building block, or as the glue. Maybe it started because I didn’t have money to actually build the spaces I wanted to describe, so I had to use “movie magic” in order to realize them, but it immediately turned into one of my main interests—to create spaces that can only exist in time, as films. If they were real spaces they would collapse, logically and physically—they do not obey laws of gravity and distance, and that’s why they are films and not 3-D sculptures.

BLVR: Is cinematic film something you’re interested in?

MR: For sure, but I’m ambivalent about actually making a feature, although I think I will at some point soon. The video part in Seven, my most recent performance piece in collaboration with Jon Kessler, is in some aspects the most cinematic work I’ve done, because the performers are not confined in contraptions. The course of events gets triggered by people mainly walking in vast landscapes rather than by the movement of materials, although the main plot is still about materials: core samples from the African soil and “chakra juice” extracted from live performers in New York. The idea of making a full-on feature film scares me, but fear always functions as a huge motivator in my process. And the most important thing is that I think I have a good idea for a movie: it’s about treasure-hunting. I just have to find the right writer. I need someone who will help me turn my sculptural sensibility into narrative film. It will still be guided by materials and will circle around a physical space.

BLVR: How so?

MR: If you think about it, in the most simple romantic comedy, there is always a cause-and-effect, right? But the cause-and-effect is not material-based, it’s behavior-based. In my videos, the cause-and-effect is material-based. It still creates a narrative, but instead of “this person did that and then this person does that,” it’s “this material spills here and then that happens.”

BLVR: Like a Rube Goldberg machine.

MR: Yes and no. Yes because of the cause-and-effect, but no because, unlike in his drawings, in my work things don’t obey physical logic, causal processes violate expectations of space and time, and, maybe most important, there is a psychological and sexual level that does not exist in his work at all. In the feature I will someday make, I want to make things happen because of people’s behaviors and fate, but materials and magic play a big part.

BLVR: How would you say making art films is different from making feature films?

MR: The process of making it. It’s a lot more free from what I understand the process of filmmaking to be. You don’t have a producer who sits on you. The budget is smaller, so there’s less stress. I’m not trying to cater to everyone. It’s obvious that we’re making an art piece, that we’re not going to try to make a wide audience understand.

BLVR: There’s a certain lo-fi quality to video art or gallery films, but yours have the look of a cinematic film.

MR: Yeah, maybe. But because technology is getting cheaper, many art videos look less sloppy, and a lot of young artists are getting really good at using software like After Effects and Final Cut, for example, so there’s this new look emerging, maybe more medium-savvy. So the lo-fi quality of some art videos becomes a stylistic choice rather than a given. I work with a really good cinematographer, Mahyad Tousi, and he’s always pushing to get the best technology affordable. But I want to keep a hands-on feeling to it, and I don’t want it too epic or clean. There’s something about a homemade quality I’m trying to keep. I want you to feel the hands behind it. The hand is never removed all the way. But I have access to technology and people who know how to operate it, like the Canon 7D with amazing 35 mm lenses, so I can get closer to the look I want. Honestly, though, it is something I have a hard time with, because I don’t like to over-dictate a cinematic “look.” I’d rather put the ingredients together—the performers, the set, the camera, the light—and then step back and let it create itself, including mistakes and glitches.

II. CHEERLEADER

BLVR: You use non-actors mostly, right?

MR: Yes, I find most of the performers advertising online, “renting out” their extraordinary skills or physics.

BLVR: Why do you choose who you choose?

MR: I’m interested in issues of alienation and ownership. Most of my performers alienate parts of their bodies in order to commodify them. For example, TallKat—a sixfoot-nine woman from Arizona—rents out her tallness. I hired her as a factory worker who operates part of a machine in the video Dough, which exploits her tallness. This brings up interesting issues for me and makes the whole thing dynamic and more playful. Also, I don’t want the performer to act. I choose people because their specific personalities or bodies fit the requirements. Instead of trying to shape them into the video, I try to find someone to work into that role who would just fit. And then they don’t really need to do much besides just be.

BLVR: Do you direct them?

MR: I think I’m more of a cheerleader than a director. I give them tasks and then yell encouragements. I try to create a situation in which their body will have to react rather than act. I create the situation where it’s obvious what they have to do. What are the tasks? What’s the conflict? And then they’ll automatically behave in a certain way that will serve the narrative.

BLVR: You began as a painter, right? What were your paintings like?

MR: My first instinct was to do these three-dimensional collages. I was never satisfied with just an illusion of space. It’s a little bit like what videos are. It was a flat space that I would put objects onto. But I was never really comfortable with the space that sculpture takes, and the maintenance, and I wasn’t satisfied with just painting. It was always something about the gesture or how I put the painting together that was more interesting to me than the actual painting.

BLVR: Do you remember when the painting-to-film transition happened?

MR: I used to use a lot of source material for the paintings, and I lost it all in an airport—all my slides and everything.

BLVR: You lost all of them at once?

MR: I moved them all at once. They were in a single bag and I lost the entire bag.

BLVR: Was that devastating?

MR: No, it was good because it pushed me to start doing what I really wanted to do.

BLVR: Were you in school?

MR: I was at SVA [School of Visual Arts, in Manhattan] in the sculpture department, and someone had a VHS camera, which actually took the coolest supersaturated images. It was this big VHS camera, and you put in the tape and you shoot and you play it immediately. I had a little puppet theater—all these mechanical animals, horses I got at the party store, fingers and cherries. I’d stage small sets and do some kind of moving—not really animation, not really stop-motion. That’s how it started. Then I did my first video installation. One day I’m gonna do it again, because I still think it’s a good piece.

BLVR: How did the film Cheese come about?

MR: It started from discovering online this product from the late 1800s developed by the Seven Sutherland Sisters. It was a hair fertilizer, hair tonic, and a cure for baldness.

BLVR: A snake-oil kind of thing.

MR: Yeah. They’re supposedly the first American supermodels and celebrities. They grew up on a poor farm by Niagara Falls. And overnight they made a million dollars in 1886, which is like a billion dollars today. Crazy life stories—seven women with floor-length hair.

III. FREAKS

BLVR: How do you feel about screens?

MR: I don’t like screens so much. I like projections more than screens. I like when the light hits something rather than coming from the back of something. I like when you can see the light, the way the light works. It feels less manipulative, more organic. The light is projected onto a surface. And with a screen, it’s a lot of little lights projecting.

BLVR: With projection, you have the dust floating in the air, the little artifacts of film.

MR: Yeah, because it is a reflection of the light, and when you have those touch screens, those flat screens, it’s not a reflection of anything—it’s a lot of little pixels that create an image.

BLVR: Do you not enjoy watching movies on computers?

MR: I hate that. But I do it. I mean, I watch it on my iPad now. But I don’t like it. What really bugs me is the color on these light screens. It’s just too cold. I don’t like the finish. I don’t like the texture. It’s too smooth. The actual screen is so shiny, and has its own physicality that takes over the image. Again, that’s the nice thing about art video—you can always control the way people see it. With a movie, there’s a lot more letting go. You release it to the world and people watch it on their iPhones.

BLVR: Control is really a big difference between the two.

MR: I think every artist is a control freak. Because, as an artist, you’re trying to control and create a new reality. You have to want to control the world, otherwise you just let reality be. You want to manipulate reality, even if it’s just by documenting it, and that makes you a control freak.