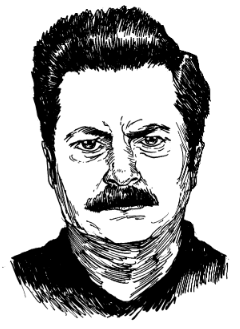

Ron Swanson is every woman’s man—and every man’s man, too. Portrayed by Nick Offerman, the mustachioed patriarch of Parks and Recreation is a true bridge-builder (literally and figuratively), charming Midwestern farmers and art-school punks alike. If Amy Poehler’s Leslie Knope is the Candide of Parks and Rec, convinced that Pawnee is the best of all possible worlds, then Ron Swanson is James Fenimore Cooper’s Hawkeye, a lone wolf who resolutely goes against the grain. They don’t make guys like this anymore.

Most people who know Ron Swanson don’t know Nick Offerman. A veteran Chicago actor, Offerman toiled for years at the Defiant Theatre, which he cofounded, and later at Steppenwolf Theatre Company, supporting himself along the way as a theatrical-set builder. Upon his move to Los Angeles, casting agents swore he was doomed to a lifetime of blue-collar roles: bus drivers, plumbers, construction workers. His early movie appearances were mostly relegated to the cutting-room floor. After years of doing meaty roles in obscure theater productions and bit parts on major TV shows, Offerman hit the big time in Parks and Recreation. These days, he’s so closely identified with the show, fans often can’t—or won’t—separate him from Ron Swanson.

Offerman lives in the hills of Los Angeles with his wife, Megan Mullally, an actress known for her role as scene-stealing dipsomaniac Karen Walker on Will & Grace. He runs Offerman Woodshop out of a converted warehouse in Atwater Village, where he builds tables, canoes, and—perhaps someday, he says—a guitar. This year, he began touring colleges with a version of his one-man show, American Ham, playing songs and offering cheeky yet practical tips for prosperity and happiness.

We were introduced through Robert Takata, a mutual friend. It went well: we met and ate meat at two of his favorite L.A. eateries—the Tam O’Shanter, a throwback Scottish restaurant, and the Red Lion Tavern, a throwback German restaurant. Offerman spoke about theater, comedy, the perils of the internet, and every other topic I offered. Loosen a man’s tongue with meat and he’ll divulge all.

—Elina Shatkin

I. BECOMING RON SWANSON

THE BELIEVER: We’ve talked about the way fans adore Ron Swanson’s disdain for moderation, that superhuman aspect of Ron.

NICK OFFERMAN: In terms of eating meat alone, everybody can understand the hero worship of someone who can eat an entire bucket of lard in one sitting. That would kill us. Ron can drink an amount of whiskey that would send me to the hospital or my grave. And that’s to be admired, to be celebrated.

BLVR: There’s just enough crossover from your life to his. Was Ron a woodworker before you came along with your woodshop?

NO: I’d been cast. I’d be on the phone with the writers and I’d say, “Hang on. I’m at my shop. I gotta shut off the band saw.” As that sank in the second or third time, they said, “We’re coming over there.” The entire writing staff got in a van and came to my shop. They immediately were like, “Your character has a woodshop.”

BLVR: How long does it take to grow Ron’s mustache?

NO: Two weeks is a passable mustache. It’s like, “Yeah, that’s a mustache.” But it takes longer for the upper nasal labial whiskers to reach the top lip. To grow the full ’stache is five to six weeks. Fun fact: facial hair is the provenance of the makeup department, not the hair department. We have this amazing makeup head named Autumn Butler, and she takes a lot of pride in maintaining Ron Swanson’s mustache.

BLVR: Are you fairly hirsute?

NO: I have a very healthy growth of both head and facial hair. People always want to attribute further superhuman powers to me. It’s funny the way the audience really seems to want me, Nick the actor, to exhibit the same machismo as Ron Swanson. They’re like, “You could chop a whole forest of trees down in ten minutes, right?” No, I exist in reality.

BLVR: Do you put on weight to play Ron? You look a lot heavier and older on Parks and Rec.

NO: No, I don’t. Although [cocreator and executive producer] Mike Schur has asked me not to trim up. The camera really does add ten pounds. We also dress Ron in a way that points out the parts of my body that are not buff. He always wears these thick shirts tucked into pleated pants. He doesn’t try to stand in a way that he’s going to be on the cover of some sort of exercising publication. It doesn’t take long at all to become Ron Swanson. It’s just incumbent upon me to have enough hair.

BLVR: You do have a great poof of hair on the show.

NO: Yeah. They add stuff to it. They blow-dry it and brush it out into this big edifice.

BLVR: That’s far more effort than Ron Swanson would ever put into his hair.

NO: I’m not sure if we ever made an episode about it, but we talked once about how Ron gets up in the morning, runs a comb through his hair, and this is what happens.

BLVR: The Ron Swanson method of hair care.

NO: I’ve never looked the same way for so long in my whole life. I always drastically changed my look for each role. It’s gotten a little tedious in real life, also, because there’s no hiding.

BLVR: Without the hair and mustache, I could see fans walking past and not noticing you.

NO: It’s definitely my best disguise. The ultimate disguise is nothing. Nudity.

BLVR: You change a lot of things to become Ron Swanson, but Ron’s laugh is your real laugh. It’s somewhere between very burly and very giggly.

NO: Is that a question? [Smiling] I’m not that calculating of a performer that I’m like, What’s Ron’s laugh going to be like? [Sounds of Nick getting Method actor–y] “Heeeheeehmmm… No, that’s too… Hohoho… No, that’s too Bluto.” Whatever comes out in a scene comes out. The older I get, the more people seem to react to my laughter. It’s a strange thing. Maybe it’s that the more curmudgeonly I get, they’re like, “Oh my god. A flower grew out of that cow turd.”

BLVR: Could you ever see Ron Swanson running for president?

NO: I think if a plan was presented to him to implode the government, you could probably get him to listen to your pitch.

BLVR: Who would his inaugural poet be?

NO: Probably himself. Or Wendell Berry. I think Ron would be a big Wendell Berry fan.

II. THE EDUCATION OF NICK OFFERMAN

BLVR: How did you get into theater?

NO: Dude, it’s strange and unlikely. I grew up in this little farm town, Minooka, Illinois. It was the ’70s and ’80s. I did not have access to much culture outside of the Top 40 radio station and the three TV networks. We’d have to drive half an hour to Morris to see a movie, and it was usually Benji or some Disney movie. On the radio it was John Denver. Super pop stuff.

My uncle would take us to get ice cream in Joliet in his Pontiac Firebird with the golden phoenix on the hood. Uncle Don was super badass. He would play Frank Zappa, but we couldn’t tell our mom. He wasn’t supposed to be playing us Zappa. That was huge for me. That was one of the only inklings I had that there was more out there. It was like, “Oh, wow. Some people are funny and awesome.” John Denver’s great, but there are other flavors.

BLVR: How did your uncle come to Frank Zappa?

NO: That’s a very good question. I always say what jumped me ahead light years in my acculturation was when I got to the theater department [at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign], the friends I made were all super cool kids. My best friend—we were two of the main forces in our theater company—was from Monmouth, Illinois. He was also from a little town in the middle of the country, but he had really cool older siblings who turned him on to good music and film. He was like, “Nick, I like you. We’re going to be friends, but we’ve got to get you caught up. This is the Beatles. This is ‘The White Album.’” I was like, “These guys are fucking amazing!”

BLVR: When was this?

NO: This was 1988. I was listening to garbage. I was really into Wham! UK and Duran Duran and Bryan Adams. My girlfriend and I would watch movies and buy the soundtracks. I loved Peter Cetera, Chicago. They were so delicious, my college years, because I had so much catching up to do. David Bowie, Tom Waits, everything.

BLVR: How did you end up in the theater department?

NO: I didn’t have an inspired idea for what I wanted my life to be. I played the saxophone, so I thought, Maybe I’ll major in music and try to go somewhere with the sax. My girlfriend, the born-again Christian, was auditioning for the dance department at Urbana-Champaign. I drove her three hours to the audition. While waiting for her, I was in the hallway of the performing-arts building—a beautiful facility—and I met some theater students. I said, “What do you mean, you’re theater students?” And they said, “We study acting and plays.” I said, “You can do that for a job?” I was completely blown away. I went home and told my parents: “You can get a job acting in plays and make money doing that.”

BLVR: Did they believe you?

NO: They did. So I went and auditioned. They have a really nice theater conservatory. It’s great training for regional theater—Shakespeare, period plays, contemporary theater like Noel Coward and Neil Simon. I was terrible when I started. I couldn’t get cast. I sucked. I improved enough that by the time I graduated, my friends and I had a theater company.

BLVR: What was it called?

NO: The Defiant Theatre.

BLVR: That’s a good name for a theater company run by twenty-two-year-olds.

NO: We were very irreverent. They valued me because I could build all the scenery. That was the deal: let’s give Nick this little part, he’ll build the set, and we come out ahead. We graduated and moved to Chicago. I started producing professionally. I kept getting slightly bigger parts and eventually became decent at acting.

BLVR: So you’re in Chicago with your own company, putting on small productions. It seems like a hard row to hoe.

NO: It made sense, though. Union or equity theater in Chicago is comparable in a general way to Broadway. Non-union or non-equity theater is a substantial enough scene that it’s comparable to off-Broadway, certainly off-off-Broadway. It’s not underground and obscure. The equity stage actors union is much more stringent in Chicago. I had to avoid the union in order to keep performing with my company, but it was important for me because it gave me a much more experimental platform. If I had just started plugging away trying to be huge, auditioning at big theaters and trying to get a job with everybody, I’d probably still be there. Instead, I stayed on the side and learned. Chicago was very much like a graduate program for me.

BLVR: You worked with Steppenwolf Theatre Company.

NO: I did. I had such a great time working with them. It was a tricky place to be. I learned over the course of five shows that to be an up-and-coming twenty-six-year-old had a certain statute of limitations in a company with a bunch of really great thirty-eight-year-olds who were still taking the twenty-six-year-old parts.

They would choose to do these shows like A Streetcar Named Desire. Stanley Kowalski, in the script, is twenty-eight. I was like, “Could I have a shot at it?” They called me and asked me if I wanted to understudy Gary Sinise, who was going to be playing Stanley. I was like, “Of course. It’s your company. You’re amazing. You’re forty… but it doesn’t matter. It’s theater.” He played it and was fantastic. It was a wake-up call: I can only go so far at this theater. If I wanted to get the best parts in the show, I had to go someplace else. I had a lot of fun doing supporting roles there. I was their fight choreographer for some shows.

BLVR: You have all sorts of hidden talents.

NO: I don’t get much call for my swordplay skills these days.

BLVR: Who else was at Steppenwolf when you were there?

NO: I did Sam Shepard’s Buried Child. Gary Sinise directed it. Sam came and did rewrites, which was crazy. He sent me out for a bottle of Maker’s Mark—which is how I learned what Maker’s Mark was. That was an incredibly fancy bottle of bourbon at the time. It still is. [John] Malkovich came and did The Libertine. I feel like he maybe even commissioned that script, but enough time had gone by that Johnny Depp played his part and he played the king. Michael Shannon was a contemporary of mine.

BLVR: Michael Shannon who’s now in Boardwalk Empire?

NO: Yeah, he’s great. When I was twenty-six, he was twenty, maybe. He was kind of a savant. We did a play together at the Red Orchid Theatre that was one of the greatest things I’ve ever gotten to do. Laurie Metcalf did a play while we were there. Fran Guinan. This guy named Jeff Perry, who I’m still very good friends with. I did Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying with him. It was the place where I first saw famous people. Ethan Hawke was in Buried Child, and Keanu came to see him. We all went out for a beer. It was where I learned movie stars are normal people.

III. CITY OF NETS

BLVR: What inspired the move to L.A.? It’s such a different world. It’s mostly about auditioning for movies and TV shows, getting a sitcom pilot. It seems like 180 degrees from theater in Chicago.

NO: An important ingredient in my decision to move to L.A. was my ignorance of that fact. It would stand to reason that Los Angeles, a bigger city with a much huger population of acting talent, would have a better theater community than Chicago. Sadly, that is completely false. The L.A. theater community is such a pale shadow of Chicago’s. But I didn’t know that.

BLVR: Did no one tell you about New York?

NO: I had not heard of New York City. I heard it mentioned on a couple David Bowie records and I thought it was a fictional city. In fact, it was the clear choice if you’re going to leave Chicago. I had a girlfriend at the time who was from Mexico, and she said, “No, motherfucker. I’ve been in Chicago for five years. We’re moving to where it’s warm.”

I had come out here to do a job for Nickelodeon, some weird kid show. I was like, “Great, we’ll move to L.A.” Then she flaked out and disappeared. She turned up back in Mexico—I think she is a really successful Mexican actress now—but I already had everything in motion, so I came here by myself.

BLVR: So you came out to L.A. for a girl.

NO: [Contemplative] Mmmhmm… in many ways. It’s a great what-if to consider how things would have turned out if I had continued to grow in a theater community. It’s possible to reach a sort of plateau in Chicago. And I did. I had this really nice year in ’96. I did a couple of the best plays I’ve done in my life. One was this crazy kabuki version of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi. It was big and carnivalesque, with elements of Tex Avery and Cirque du Soleil. I think it was the greatest show our company ever did. Then I did this seven-hour play called The Kentucky Cycle by Robert Schenkkan. It’s nine one-act plays, all set on a piece of land in Kentucky. They go from 1776 to 1976. It’s really, really wonderful, and I won a Chicago theater trophy.

BLVR: What do they call that?

NO: Joseph Jefferson Awards.

BLVR: The Jeffys?

NO: We call them the Jeffs. I had a couple of role models. It became more and more clear to me that while they were my heroes in the theater, they were also kind of sad. One of them was a drunk, one of them never had an apartment. He always slept on his girlfriend’s couch, but his relationships would be volatile. In three years, I helped him move to five different couches.

BLVR: How long does it take to move someone to a couch?

NO: About two hours.

BLVR: In Los Angeles, you were getting typecast as blue-collar guys, being told this is all you’d ever play: truck drivers—

NO: Plumbers. I’d go to a meeting, they’d look at my résumé, and they’d have no idea what all these theater words were. When I got to Los Angeles, one of the things I was told is: you should watch every show on TV, at least one episode, so that when you audition you know what kind of bullshit they’re selling. Anytime I would hear that, I would think, I’m not going to watch any TV shows. That way I’m guaranteed to be different from all the douchebags trying to act like James Van Der Beek.

BLVR: That’s how you flubbed the Dawson’s Creek audition, isn’t it?

NO: It is.

BLVR: You would have been a good Dawson.

NO: It would have been another way to go. He would have changed a tire a little more quickly.

BLVR: Were you not cast much the first two years you were in Los Angeles?

NO: I did a couple plays that actually did me some good. I did a Mike Leigh play called Ecstasy. Some casting directors came to it. I began to work. I did a live episode of ER. I was getting a few nice roles a year, but it was two steps back. I had been doing two hours’ worth of excellent literature and now I was excited to get five lines on NYPD Blue.

I never went too long without a job. The problem was a lot of the early jobs here are almost more demoralizing than unemployment.

BLVR: At what point did you meet Megan [Mullally]?

NO: It was sort of the end of the rocky period. In 2000.

BLVR: Was she the harbinger of better times?

NO: Absolutely. She was literally the answer to my prayers. I was drinking a lot of bourbon. I was miserable. I was starting to get work, but it wasn’t remotely satisfying. It was garbage compared to the theater I was doing. I realized what I needed to do was find a piece of theater that I could sort of reestablish my manhood upon. I needed to do a play. [Casting directors] Nicole Arbusto and Joy Dickson hooked me up with a play at this company called the Evidence Room.

BLVR: That used to be in the Bootleg Theater, right?

NO: Yeah, it’s a long, sordid tale. The landlords of the Bootleg were in our company. I helped them build that space into what it is. That was where Megan and I met.

BLVR: What play were you doing?

NO: The Berlin Circle. It was the first play in the space. I think I did eight shows there over five or six years. It’s a very magical place for us. It was considered sort of the most relevant underground-theater company in L.A.

Megan and I, neither of us knew anyone else in the whole production. We had both come to it in the same way, where we were like, “I really want to do something good in theater right now.” It was right after season two of Will & Grace.

BLVR: So she was already pretty famous.

NO: I was living in a basement in Silver Lake and hadn’t had a TV for ten years. I hadn’t seen Will & Grace. When I went to audition for the play, they said, “We have Megan Mullally.” I was like, “I know you’re saying that as an incentive, but I’m not impressed. I’m from the theater. I don’t need some TV chick in the play.”

At the first read-through, Megan was so funny. And cute. But that didn’t hit me yet. We were both staunchly single at the time. I was like, “Whatever. She’s cute.” I was in some kind of denial.

BLVR: Was she funny in the role or in person?

NO: Unbeknownst to me, everybody else was really freaked out by her because they were huge fans of Will & Grace. So we do this read-through, and she was so funny, masterful and smart. I immediately went up to her and I was like, “Hey, I’m Nick. You’re super funny. I think this is going to be really fun. Anyway, take it easy. I gotta go put my tool belt on and build some shit. You can watch—if you want.” She thought, I guess they haven’t cast this part yet, and they’re having the plumber friend read it. Partway through, she thought, The plumber’s pretty good. They should cast this guy.

IV. CONTRARY TO PUBLIC OPINION

BLVR: When you go to a college, do people expect something closer to Ron Swanson than Nick Offerman?

NO: At most of these schools, the students run the activities board. A lot of the requests will say things like “We don’t even care if Nick Offerman shows up. We just want Ron Swanson.” They say things that they clearly don’t understand might be hurtful. [Laughs] They’re being enthusiastic, but I would say to them: we love Ron Swanson in doses of two minutes a week. Ron never has more than four or five lines in a scene. If you had Ron Swanson for ninety minutes onstage, he would probably talk to you for forty-five minutes about how to shave your own ax handle.

BLVR: Where did you take up woodworking?

NO: In Chicago. By the time I left, I had my own little shop in a warehouse where I was building scenery. When I got to L.A., I couldn’t find the same kind of gig. I looked into a few shops, but I was too honest with them. What I should have done was not tell them I was an actor. Just start working there and after a couple months, say, “Oh, I’ve got an audition.” By then, they’d love me and it would be OK.

BLVR: How did you get into canoeing?

NO: Right up the road from where I grew up was Aux Sable Creek. [Offerman pronounces it “crick.”] I would take the ladies down the creek in my canoe. There was a beaver dam over by the Haaverdings’ farm. At dusk they would swim by the canoe and slap their tails. It was quite erotic.

BLVR: Any thoughts of canoeing down the L.A. River?

NO: Sure. The main reason I’m not running out to do it is I feel a few artistic hands have done it and written about it.

BLVR: Can you canoe it unironically?

NO: Canoeing the L.A. River unironically is like doing non-union theater in Chicago. Not a lot of people are going to hear about it, but you have the beauty of performing in a Harold Pinter play and you’re just happy to have done it.

BLVR: How did you become such a contrarian?

NO: When I was in fourth grade, we were learning vocabulary words, and the word nonconformist came up. The teacher said, “It’s somebody who whatever everybody is doing, they do the opposite.” I remember raising my hand and saying, “Mrs. Christiansen, I would like to be a nonconformist.”

BLVR: The business of engendering mirth is not an easy one. The thing that struck me about your “Ten Tips for Prosperity” was that most of them were very basic sandbox rules. Except “Use intoxicants”—I don’t know a lot of hammered five-year-olds.

NO: I wouldn’t start pushing that until eleven or twelve. There’s a lot of common sense to it, which I feel like we have lost touch with. If I put down my tweeter machine for a minute, I actually can communicate with people. As an aside, astonishingly, I just started doing Twitter. Yesterday.

BLVR: Last time we talked, you said you and Megan had consciously chosen to be neo-Luddites, avoiding Facebook, Twitter, using a shared email address.

NO: Just answering emails is such an insane monkey on my back.

BLVR: Why the sudden change?

NO: I was writing an email to Conan O’Brien and Rob Corddry, who are my two friends with the most followers on Twitter. I was going to ask them to tweet the link to the trailer for this movie I produced. It occurred to me that my reticence to know anything about Facebook and Twitter was not proper etiquette. It isn’t cool to make your friends go to the trouble of maintaining a Twitter thing and exploit it. It would be like, “Hey, you own a series of billboards. Would you mind advertising my product on them?” If you want to do this, do it yourself. Or shut up.

BLVR: Paddle your own canoe. Rule number ten.

NO: Paddle your own canoe. It’s been a difficult learning process. I sent one tweet yesterday about watching my wife’s show, which premiered last night. I can’t bring myself to do it again. Yet. I feel I need to address the change in policy. I just have to figure out how to do that.

BLVR: Maybe a press release that says: “Nick Offerman no longer hates the internet.”

NO: That’s the thing. I still hate it. When I signed up, my assistant sent me my user name and password. Then it says, “Sign up for who you want to follow.” I look at “entertainment.” Alec Baldwin. I love Alec. So I sign up for Alec. By the time I get to the next step, it buzzes and there are thirty-eight tweets from him. The tweets are like “Man, Elvis was so cool,” and a link, presumably to something about Elvis. And another tweet: “Seriously, check out how cool.” A minute and a half into signing up, I’m like, get Alec Baldwin off! Alec is very much a hero to me, but I don’t want to be receiving his Twitter messages.