At first, the cab driver couldn’t find it; the empty fields to the left and the low trees to the right were covered in snow, and there was no looming Hamptons mansion at the end of the road. “I don’t think there’s anywhere else here,” he said. But then it appeared: a modest, low-slung house glimpsed through a tunnel in the trees. As we pulled into the drive, it was clear that Peter Matthiessen’s home for the last six decades wouldn’t be considered a normal home anywhere. An enormous skull—the cranium of a fin whale—was braced against a wall of the house, and clusters of other artifacts rested half-buried in the snow: driftwood, stumps, shells, small boulders, sculptures. I rang the doorbell and no one answered, and for a moment it was completely quiet: rain dripped off a row of icicles hanging from the roof. And then a kindly, deeply lined face peered through the glare in a pane of the front door.

What to say about Peter Matthiessen? There was no one quite like him: a writer and thinker, a naturalist and activist, and a fifty-year student of Zen Buddhism who, as his publicist put it, “lived so large, and so wild, for so long.” He was the only person ever to win the National Book Award for both fiction (Shadow Country, 2008) and nonfiction (The Snow Leopard, 1979), along with a bushel of medals and prizes for his elegant but unsentimental books (of which there are at least thirty), most of which concern the wild places, animals, and people “on the edge,” as he said, of the farthest parts of the globe, where pre-human landscapes and premodern pasts are (or were) still visible.

These edges are, more or less, where he spent his adult life. A précis of his travels is a bewildering list, and includes the Himalayas, the islands of the South Pacific and the Caribbean, the Mongolian steppe, Africa from the Serengeti to the Congo basin, South America from the Andes to the Amazon, the boreal forests of North America and Siberia, and a “musk ox island in the Bering Sea”—and that’s far from exhaustive. These travels would be remarkable enough, but he also cofounded the Paris Review, in 1953 (while working undercover for the nascent CIA); a few years later he was a struggling novelist and commercial fisherman using nets and dories off Long Island’s South Shore. Sixteen years after that, he was working as a labor activist with Cesar Chavez, and thirty years on, his book In the Spirit of Crazy Horse: The Story of Leonard Peltier and the FBI’s War on the American Indian Movement (1983) resulted in multimillion-dollar lawsuits against him and his publisher by a former governor of South Dakota and a former FBI agent (both lost their cases). And in Blue Meridian: The Search for the Great White Shark (1971), he followed a team of divers trying to capture the first underwater images of the animal. The resulting film, Peter Gimbel’s Blue Water, Blue Death, is credited with inspiring Jaws.

Above all, Matthiessen followed his own muse, and though he avoided repeating himself, all of his books combine his searching, acerbic intelligence with his gift for evoking landscapes and people, and all are shot through with glimpses of a reality beyond human understanding—a bit like what Werner Herzog calls “ecstatic truth.” It’s a marriage of the dignified and the avant that can make his writing seem, at times, like a really good translation from another language. Both nature writing and what’s now called creative nonfiction owe him a huge debt, though his pure fiction tends to be overlooked (Far Tortuga, the experimental novel that preceded The Snow Leopard, doesn’t get the notice it deserves). His last book, the novel In Paradise (Riverhead, 2014), probes a different edge; it takes place at a Zen meditation retreat in Auschwitz, following his own experiences there at similar retreats in the late ’90s.

Inside his house, everything was orderly, earth-toned, and wooden, both genteel and rough-hewn. Photographs of the people of the New Guinean highlands he visited in 1961 (vividly recalled in Under the Mountain Wall: A Chronicle of Two Seasons in Stone Age New Guinea), some of them taken by expedition mate Michael Rockefeller, surrounded a weathered baby grand piano; a pair of binoculars rested on its back on the piano’s lid. Smooth river stones, one of them incised with an elongated face that might be the Buddha’s, lined the sills of tall windows, among potted maidenhair ferns and a blooming Christmas cactus. In the backyard, two wooly-coated deer flecked with ice craned their necks to suck bird seed from a feeder, displacing a little cloud of cardinals and white-throated sparrows.

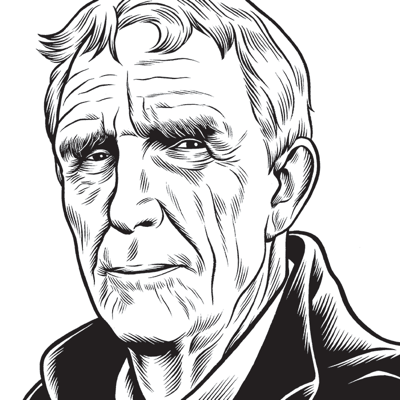

We sat in a cramped spare room he was using as a study, since the small outbuilding where he’d done the bulk of his writing was losing a battle with mold. He took a swivel chair beside the computer where he was working on yet another book: a memoir. It was a form he regarded with suspicion, and he was still finding its structure, which he compared to the branching leaves of giant kelp. I had to place my recorder close to him to catch his deep, conspiratorial rasp, but there was plenty it didn’t capture: he talked with his face and his hands as much as his voice, widening his eyes in surprise or crinkling them in mirth, fluttering his fingers to dismiss the encrustations of “lush writing” or opening his palms in surrender to a great line of prose. Or he enlisted all his features in sudden imitations of people or animals: an Inupiat pilot swatting a mosquito, a grizzly bear recoiling at the sight of a human, a white shark trying to swallow an outboard motor. The landscape of his creased forehead, wild eyebrows, and silver hair suggested stormy weather, but his eyes were a surprisingly mild, even innocent, blue. Only a month before his death, at the age of eighty-six, he was still clearly the man from the jacket flap of The Snow Leopard, and his memory for the smallest details of books he wrote half a century ago was ironclad. The pad of his right thumb was stained with green ink.

—Jonathan Meiburg

I.

THE BELIEVER: So those are Michael Rockefeller’s photos on the wall out there?

PETER MATTHIESSEN: Those aren’t all Michael’s, but I can show you the ones that are. Over the doorway you can see two of the spears: there, those incredible long spears.

BLVR: They look like they mean business.

PM: They didn’t like to throw those spears right away, because they were too much trouble to make. There’s no metal at all, you know—they make them by taking these saplings into cold mountain water and scraping them with stones; that was a few weeks of work. Their technique was to use a bow and arrow until the guy was really helpless and then they would come forward and throw it. They were scared somebody from the other side would come up and run away with it!

BLVR: That book, Under the Mountain Wall, might be the strangest of all your work.

PM: Yeah.

BLVR: Why did you write it in the way that you did?

PM: Well, actually, I went out there and I had no such intent at all. Remind me to go back to New Guinea, but it’s kind of like Far Tortuga. Far Tortuga came out of a fact article for the New Yorker, called “To the Miskito Bank.” I had to keep going back to Grand Cayman, partly because of the rascality of my contact down there, who was a sea captain of somewhat the same persuasions as Copm Raib [a character in Far Tortuga]. Anyhow, I piled up a lot of expense money, so it was very embarrassing for me. I came back after one year, and I went in to see [New Yorker editor William] Shawn. And I said, “Mr. Shawn, I have your fact piece, and I think it’s going to be OK, and I just want to tell you since you spent a lot of money on my expenses”—and I pride myself on keeping my expenses low, so he knew I wasn’t gouging him—“I’m going to save my best stuff for a novel.” I said, “I’m so powerfully affected by a feeling down there that I’ll give you your fact piece, but I’m saving the best stuff back.”

And Shawn said something—and I’ve been dealing with magazines for years, and fighting with editors all the way over cuts and edits, and no pay, and whatever—but Shawn, without any hesitation at all, said [in a Shawn voice], “Mr. Matthiessen, you do what’s best for your work!”

And tears just—arced out of my eyes, you know. I was so moved and touched by that.

So I did. But then I went even further with it. I not only took stuff out for a novel, but I began to see that I didn’t want any of the furniture of a novel. I didn’t want any “he said”s or “she said”s, ordinary similes and metaphors. Just—get all that out of there. And I think that was partly because of At Play in the Fields of the Lord, which I think is pretty well written, but it’s ornate by comparison. It’s full of metaphor and simile and, you know, lush writing [laughs]. For Far Tortuga, I wanted it absolutely spare. Just a line of birds on the horizon.

My great question, I would say, comes from Turgenev, from Virgin Soil. One of the characters kills himself, but he leaves a note, and the note says: “I could not simplify myself.” [Drops jaw] Boy, that’s like that Akhmatova line, the epigraph from In Paradise—

BLVR: “Something not known to anyone at all—”

PM: “—but wild in our breast for centuries.” Yes, you know. Oh! [Groans as if smacked in the chest] I know that feeling so well. It’s been my great, great aim in life, simplification. Total failure.

BLVR: You wanted me to draw you back to the highlands of New Guinea.

PM: I figured if I brought the anthropologists in, then you almost automatically have to deal with the personalities involved. And there’s a great deal more complication. I hated the National Geographic style of writing, you know: “Suddenly I heard a noise behind me.” I didn’t want to write another expedition. I just wanted the sense of a pure Stone Age culture.

BLVR: Why did you go in the first place?

PM: We were trying to discover why people go to war, in a circumstance where people went to war regularly—loosely, once a week. [The men of neighboring tribes] would challenge each other and go out and fight and then take nothing; they did this just for their own pecking order or status, or whatever. And they would adjust the combat so it was fair—one side could bring in more men if the terrain was more favorable for them, for example. It was fascinating to watch it.

And the women would come up out of the trenches where they were working, and they would sit on the hillside and kinda—cheer. But the cheering was mostly jeering: “He can’t even get it up!”—you know. And they’d kill one guy, or even come close to killing him, and then—they’d go home. They didn’t have to have mass slaughter. So in a sense it was very civilized. And we found them enormously gentle and kind with their own little kids, and they were lovely with old people. They really had a very strong civic sense; they took care of people who needed help.

BLVR: What did you learn about war?

PM: It’s a simplification to say that the men went to war to maintain their dominance over the women. The men would help dig agricultural ditches because they were superb farmers. That was very heavy lifting work. But then they just preened themselves, and put bird-of-paradise plumes [in their hair], and smoked dope.

II.

BLVR: A thread that runs through In Paradise is the tension and connection between erotic love and a kind of sacred love, or maybe what [the central character] Olin calls “earth apprehension.” You refer to mankind in the book as “this two-legged crotched creature that knows it must die.” And somehow crotched is the most jolting word in that sentence.

PM: Well, the great penalty for whatever we do is knowing that we’re going to die. There’s no other animal that knows that. They never do. Even the ones that are scarce and rare, if they don’t feel good, they just get up under a rock so that they’re not preyed upon so easily. But we’re the only one that knows… it’s curtains [grins].

BLVR: I guess what I wanted to get at there, though, is a submerged erotic element in your writing. I feel like that’s more overt in In Paradise than it is in almost any other book of yours. Which is funny for a book that’s set—

PM: —in Auschwitz.

BLVR: In Auschwitz.

PM: Well, is it more overt, or is it that it’s so out of keeping with what should be the spirit there, from a PC point of view? That it seems to stand out more, just because it’s already reacting with, well, “This is Auschwitz; you can’t do this.” Olin has to recognize that there is a strong, erotic—that he is drawn to this girl, this woman. And he’s horrified at himself, because he has plenty of rigorous, New England training.

BLVR: The Snow Leopard also touches on the loss of Eros, or the loss and regaining of it. Near the end, as you’re sort of reentering the world, you mention that you’re ready to eat, sleep, make love, so it’s in there, too.

PM: It is. But it’s in life, isn’t it? I think I’m quite a normal person in this regard—but I don’t want to dwell on it. I don’t like so-called “sex scenes,” unless you’re getting some kind of comic thing out of it. There’s a couple of funny scenes in Shadow Country that are totally ribald and outrageous—and in a way, I also see erotic love in that way. It just makes fools of us, you know, physically and emotionally. I also very rarely write about cities or urban people—especially urban people of our own region. ’Cause it’s too well covered, my god! I mean, the New Yorker has saturated the world with this stuff for years, and I never wrote fiction for them; I didn’t want to. I wrote nonfiction for them. I like my own beat—I like to be out there on the edge with people who, as I say somewhere, haven’t got time to be neurotic.

BLVR: Neurotic is a funny word to use, though, because when you accepted the National Book Award for Shadow Country, you said you’d always had a “neurotic” feeling that your fiction wasn’t as appreciated as your nonfiction.

PM: Well, yeah—did I say “neurotic”?

BLVR: You did!

PM: Well, that’s OK. I can have my neuroses, but I’m not particularly interested in writing about them, because it is exhausted, you know, between all these memoirs and tell-alls—and novels. It’s not the stuff that I like.

BLVR: What do you think people haven’t noticed in your writing?

PM: Humor.

BLVR: Humor?

PM: Almost never have I been considered funny. Once, at a book signing, a man came up and said I made him laugh, and I just [mimes bear hug] embraced him! When they did that documentary about me a few years back, they came here to the house for a private screening. And at the end of it, [Matthiessen’s wife] Maria said, “It’s very good, it’s very generous, but you’ve missed two things: you’ve missed that he’s funny, and you’ve missed that he’s a rascal.”

III.

BLVR: Your work often seems haunted by a longing for a lost paradise—one that can be glimpsed but never quite regained. Sometimes this is embodied in actual places or people; I’m thinking of Samling monastery, for instance, which you couldn’t reach in The Snow Leopard, or the leopard itself, or the woman in the da Vinci painting in In Paradise. But most interesting to me is that you seem to feel its absence because of a sense of having known its presence. Can you talk about where that comes from, or where you’ve seen it, in your life?

PM: Yeah, yeah. [Long pause] I think I saw it earlier, in my youth, and maybe also as a very small child. [Widens eyes, leans back, and becomes almost preverbal] All this… incredible stuff roaring by, you know, noises and lights and matter, and you’re eating worms and stuff—“What is all this?” You know?

And that, in a way, is a kind of an early paradise that we do lose, the nondiscriminatory—we don’t discriminate, we try everything. But then you have to discriminate and sort out what you don’t like and whatever, but gradually when you do that then the bad crusting-over comes. Opinions, and anger, and indignation—as we say in Zen, “greed, anger, and folly.”

But in addition to that, I have an inner memory of flashes of light happening during my youth. I had a definite one on a troop ship going from the Golden Gate to Pearl Harbor. A twelve-day storm. And I was up on deck, I had fire watch, if you can believe it, and you couldn’t hardly hang on through the waves! But I’m glad I did, because I had a shelter under an Ellis, one of the landing craft, across the bow. And the rest of the ship smelled so bad, vomit, you know, it was awful. But during that time, there was one night when it was so incessant, these waves crashing. And it sort of—obliterated me. I was suddenly a part of the wave. There’s sort of an attempt to describe it in [Matthiessen’s third novel] Raditzer, on the voyage out.

Then, of course, I did drugs, for most of the ’60s. But they don’t ever quite qualify. It’s wonderful, but it’s like you’re watching from an aisle seat, you know, and you’re not quite there, because your ego is—pshht! It’s gone; you’re like a kid in a sandbox. Everything’s manifesting, and you’re manifesting, too, but you don’t know it, or you no longer know it.

BLVR: There’s that scene in Far Tortuga that seems almost like a warning, when the characters actually do reach one of these Olympian places, this perhaps-mythical island—

PM: —but they reach it as it’s being despoiled.

BLVR: I was angry at you for that.

PM: [Grins] Well, Desmond, you know—he had to have his moment.

BLVR: When you look at what we’ve done to the planet, and seem hidebound to continue to do these things, it’s hard to avoid the feeling that this place is going to be better off without us. How do you avoid this line of thinking?

PM: Kurt Vonnegut used to live up the street, and he came down here one day, and he put a sticker on my truck. And it said: YOUR PLANET’S IMMUNE SYSTEM IS TRYING TO GET RID OF YOU. I still have it out there—it’s coming off; it’s tattering. He’s the one who gave me that model of the HMS Beagle. [Motions to a glass case by the front door]

BLVR: I wondered where that came from.

PM: It’s a good model, too! I think he didn’t know what was going to happen to it, and he didn’t have much faith that he was going to live much longer. And one morning, he just appeared. It’s got a little sign in there and it just says: “This is my gift for Peter Matthiessen.” It was wonderful. And he wouldn’t even stay for lunch.

IV.

BLVR: What did you think about Jaws when it came out?

PM: The movie, or the book?

BLVR: Either one.

PM: I’ve always heard that [the writer] Peter Benchley was a very nice man, so I have nothing against him except for possibly borrowing the mood of my white shark description in the beginning. But I thought it was—I mean, it’s not my kind of book. I read it only because of the movie we made [Blue Water, White Death], because Jaws made the money and we subsided into obscurity [laughs]. The movie… you know, Quint is based on a guy called Frank Mundus, who was a Montauk guy; he was the big shark hunter. That’s where that film [Blue Water, White Death] really began, because [filmmaker] Peter Gimbel was down on the docks there. He was at Salivar’s bar, and they had a mounted head of a white shark, and Gimbel immediately put himself to that test: Would I be afraid of that? And I thought—God. I mean, if you’re not afraid of that, you’re an idiot.

BLVR: And yet you took the test, too. You got into a cage and went down.

PM: Yes. I wanted to see it. And I was frightened, because I was the one holding the bait [stretches out his arms, eyes averted], and this—fucking thing was hitting the bar like the Orient Express, I mean, just—whaaam!—and it was just aluminum—Jesus! [Laughs] We had one scene there where [cameraman] Peter Lake was in the cage and the shark just opened it up like a tin can. He could have picked Lake out of there so easy. But he wasn’t after Lake. He was after the flotation tanks, which glint.

BLVR: I think of Blue Meridian as the point at which our cultural obsession with great white sharks really began.

PM: That’s giving me more credit than I deserve. I think that Jaws came out of our movie, but that wasn’t my movie. My book was Blue Meridian, and I was alone on that expedition. I was only, you know, a chronicler. Blue Meridian actually appears, though, in a stack of books in the captain’s cabin.

BLVR: In the movie Jaws.

PM: That was to console me, I guess [laughs].

BLVR: What do you feel most fortunate to have seen in your life?

PM: [Long pause] It might be the whole panorama of the high Himalayas. When it’s in all its glory, and you’re up there at fifteen thousand feet. It’s just so… it’s so stunning. But I’ve also been at sea with a hurricane, with all the big waves coming over the bow. I don’t know. I find the whole thing so wondrous. I can be very excited by something I find in my own yard, you know: “What can this be?” So—I don’t know. I’d have to think about that.

BLVR: It’s not really a fair question. I’ve kind of resisted keeping a list of birds for that reason—I love birds, but I don’t want a life list, or a top ten, or whatever.

PM: At one time I was a lister, good and proper. I mean, I really enjoyed looking at birds, too, but I had all the birds on the eastern list, and a lot of birds on the western list as well. But then I lost that Peterson Field Guide, and I never tried to refill it. And now when I go and do a field trip, I keep only a sort of vague list of that trip. I don’t even know why I do it; I never look at it again. And I don’t have a world list. I think that as soon as you start doing that, you’re in it for the wrong reason.

BLVR: One of the images in your work that’s stuck with me is a little yellow bird. Do you know the one I’m talking about?

PM: In the Urubamba River, in the gorge [in Peru, in The Cloud Forest].

BLVR: Yes.

PM: Probably a yellow warbler, you know, that time of the year.

V.

BLVR: Why did you choose fiction for In Paradise, when it’s drawn so directly from your own experience?

PM: I knew I couldn’t convey anything of what I felt in nonfiction; I couldn’t go deep enough. Like the old artist said, it has to go through art to see it again, to feel it, to make it new. And even now, wait and see, I’m going to get a lot of flak, just like Styron, poor Styron. He went through hell on Sophie’s Choice because Sophie was Polish [Catholic], not Jewish. I mean, “The Jews own the Holocaust”—there’s a lot of feeling like that.

BLVR: It seems like one of the points of In Paradise is that everyone owns the Holocaust.

PM: Not only does everyone own it, but ultimately [everyone] could be on either side.

BLVR: So much of your writing’s been concerned with animals, with wild landscapes and creatures, that it was a little strange to me to read a book of yours in which there weren’t any.

PM: No. Olin sees a falcon when he’s out on the platform.

BLVR: Now I have to throw out my theory.

PM: And he also sees those rooks, and some of those crows, the hooded crows of central Europe. And then there are the deer prints. I couldn’t believe that when I saw it, these deer prints in the snow around the crematoria—it was extraordinary. I climbed down into one of the gas chambers, and I was astonished at the microbial and fungal life already—I say “already,” after sixty years—claiming it, reclaiming it. I loved that.

BLVR: You’ve expressed some discomfort with memoirs in general before. When I saw you speak in Texas a few years ago, you said, “The problem is that you always come out looking pretty good.” And yet here you are working on one. What do you think you can reveal about your life that you haven’t already?

PM: I don’t know, very little of interest! It’s just that I have an awful lot of sorta great stories and encounters, and it would be fun to have ’em set down. But you risk all that name-dropping, and vaunting yourself. Even when you don’t intend to, you tend to slide things in your own favor. The only way I can do it is to be really self-deprecating, and laugh at myself at every opportunity.

BLVR: Does that ever feel false?

PM: Mm, no. I can take a hit. The guy who was really good at that was George Plimpton. He was an expert in self-deprecation.

BLVR: Are you surprised at the longevity of the Paris Review?

PM: I once tried to get Plimpton to quit after [the Paris Review] had been in New York a number of years; I led a little resistance, or rebellion. Every time we’ve gotten a new editor, I’ve sort of thought, This is a good time to, you know, wrap it up! [Laughs] But I didn’t realize—I mean, I knew George, of course, since we were little boys, but I didn’t know how built into his life that magazine was—that he needed it very badly. And putting it to death would be like putting him to death.

BLVR: Has there been a book you thought would connect with an audience that didn’t?

PM: [Pause] No. But then I’ve always thought my books pretty much got what I expected them to get. I’m not a best-seller writer. The only best seller in the pack is The Snow Leopard, and The Snow Leopard had a horrible beginning. It was like the beginning of this last Super Bowl.

BLVR: [Laughs]

PM: No, really! You know how the book section [of the New York Times] comes out a week early, and all the editors get it. So on the Monday of the week it was supposed to be reviewed, my editor Joe Fox called up and said, “Get ready. Buy yourself a yacht.” You know, “You’ve hit the big one!” Because it had the whole front of the Sunday New York Times Book Review. And in those days, they would make sandwich boards, and they’d put them around, and they’d put one up by the counter [at stores], and whether you read it or not, you bought it, I don’t know why. Everybody had to—you had to have that book. And it would have gotten that.

But no one ever saw that review, or that issue, because it came out on the first day of the New York Times’s ninety-day strike. So there went my chance for a best seller. Now, I’m not complaining; over the years it sold pretty well, and it won the National Book Award eventually, or whatever, but it wasn’t biiiig, you know—the kind of seller that would put you on the best-seller lists for book after book.

BLVR: In music we wrestle with this, too, of course; you spend all this time making a record, and then you put it out, and you brace yourself for the reviews, and it’s impossible to know whether you’re going to be exalted or condemned.

PM: It can be. We had a book, The Tree Where Man Was Born [about East Africa]; Dutton published that, and they got Eliot Porter to do the photographs, and combined the two. And that was reviewed for the New York Times by Peter Beard. Now, Peter Beard [was considered] the young American who owned East Africa. He was the authority and the ego, I guess. And they gave it to him to review, and he trashed it, really, he just trashed it. And we didn’t know that; we didn’t know what was coming up.

But Truman Capote, who lived out here, he did know. And he called me up and said [in a Capote voice], “Oh my god! What they’ve done to you!” He—Truman, he was such a funny mix of things. He hated his friend being reviewed that way. But he also loved it [laughs]. But either way, he tipped me off, so I called up the publisher, and I said, “Listen, we’ve been sandbagged.” And [Dutton publisher] Jack Macrae said, “My god, I put a fortune”—he was a tightwad—“I put a fortune in this book!” You know, he’d sent it to Italy for the printing—and it was a good job, no question. And, I said, “Well, I can only tell you we’re getting trashed on Sunday.” So he called them up ahead of time, and I’m glad he did. But he really blew a gasket. He said, “How can you? You knew damn well when you gave it to Beard that it was gonna get trashed, and that’s not good editing. That’s a hatchet job.” And they never ran that review.

BLVR: To return to The Snow Leopard one last time, sales aside—do you remember how you felt about it before it went to press? I went to see the manuscript at the Ransom Center, in Austin, partly because I was curious how much of the finished text was in your field notebooks. And I noticed that most of the pages were crossed out in different colors of ink, sometimes with what I imagined might have been some vehemence, or impatience.

PM: No. It was to keep my own mind clear, because I had my own system in there. I put all the “data,” so-called, on the right-hand page, and then anything I think of later on the left, so all of that’s in the same area. It makes it much easier to rewrite; I recommend the method. But you often do plagiarize yourself—you think you’ve done it and you haven’t, or vice versa. So if I know it’s in the text and I’ve included it, I scratch it out.

BLVR: What did you make of it when you were done?

PM: Very early in that book I said, If I can’t get a good book out of this, I ought to be taken out and shot.

VI.

Maria Matthiessen, Peter’s wife for over thirty years, gave me a lift back to the train station. (You might recognize her name from a recent episode of This American Life built around her guidelines for boring subjects to avoid in conversation.) Her German and English parents, who raised her in East Africa, were easy to see and hear in her precise accent and no-nonsense manner, and she’s as strong a flavor as her husband; I wished I’d interviewed them together. Earlier, during lunch in their kitchen, I’d been struck by how sturdy their partnership appeared, but also—remarkably—how distinct they’d remained as individuals, even after many years together.

We talked a little about Peter’s recent illness, which loomed over both of their lives but also seemed to have put them in a fighting mood. She was frustrated by feelings of dependence that didn’t sit well with either of them. “You can’t go anywhere, you can’t do anything,” she said. “You’re in god’s waiting room.”

At the station, the morning’s snow and ice had turned to light rain, and the sky, the road, and the bare trees were soggy, smeared, and gray; a pair of crows chased each other around the empty parking lot. Maria decided to wait with me, wrapped in her green-trimmed black overcoat, and we talked until the train came. I took a seat by a window, where I could see her standing on the edge of the platform, and she was still there, waving, when the train pulled away.