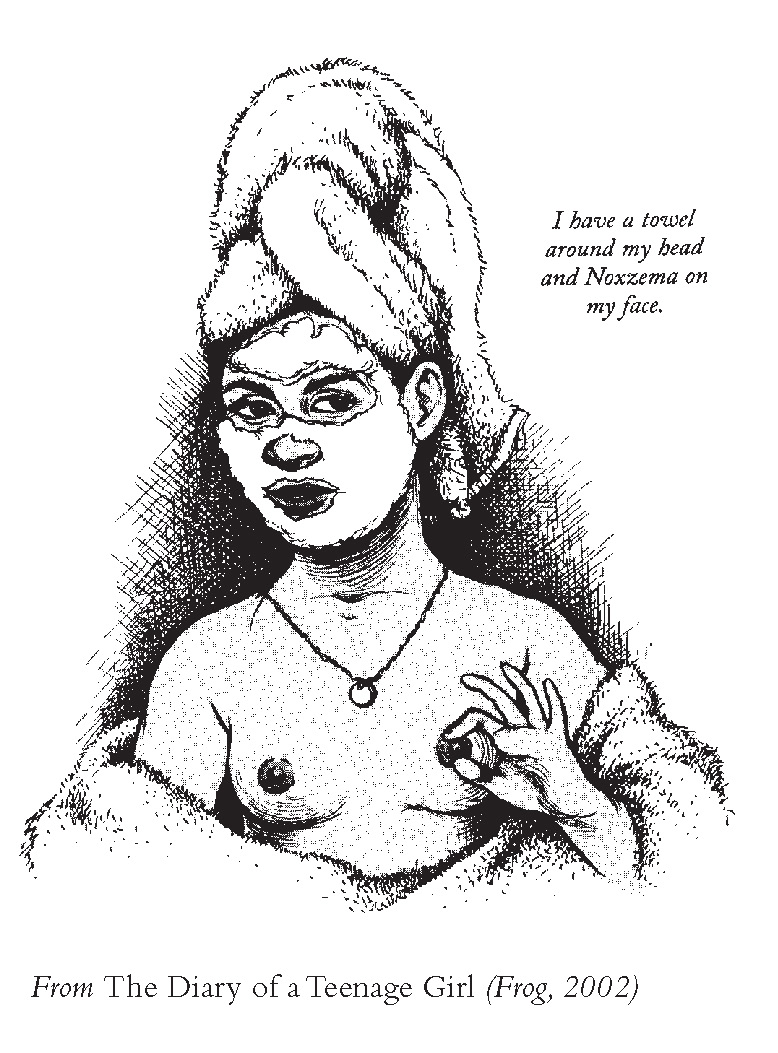

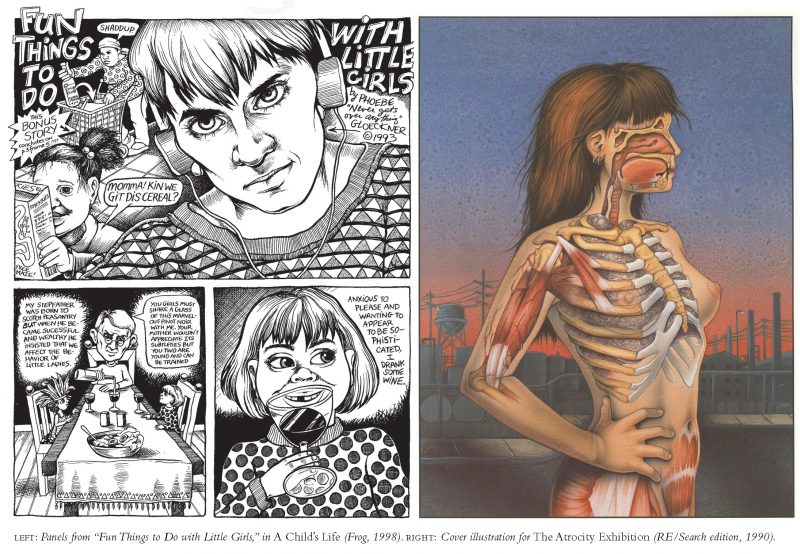

Phoebe Gloeckner began her career as a medical illustrator who published comics on the side in volumes such as Twisted Sisters: A Collection of Bad Girl Art, and also did experimental illustration for work such as J. G. Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition. In 1998, she published her first book, A Child’s Life and Other Stories, a comics collection that has at its center several hard-hitting semiautobiographical stories featuring a character named Minnie. Her next book, The Diary of a Teenage Girl: An Account in Words and Pictures (2002), takes place in 1970s San Francisco and focuses on one year of fifteen-year-old Minnie’s life—a year in which she starts an affair with her mother’s predatory boyfriend, gets kicked out of several schools, runs away to join Polk Street’s gay and drug subculture, and draws many comics. Diary, the most unabashed record of teenage sexuality I can think of, is a remarkable formal object, roughly half Gloeckner’s actual diary from the time and half narrative she formed as an adult. The story moves forward in both prose and comics sections, seamlessly alternating back and forth, while also featuring many spot and full-page illustrations. (The New York Times wrote that Gloeckner “is creating some of the edgiest work about young women’s lives in any medium.”)

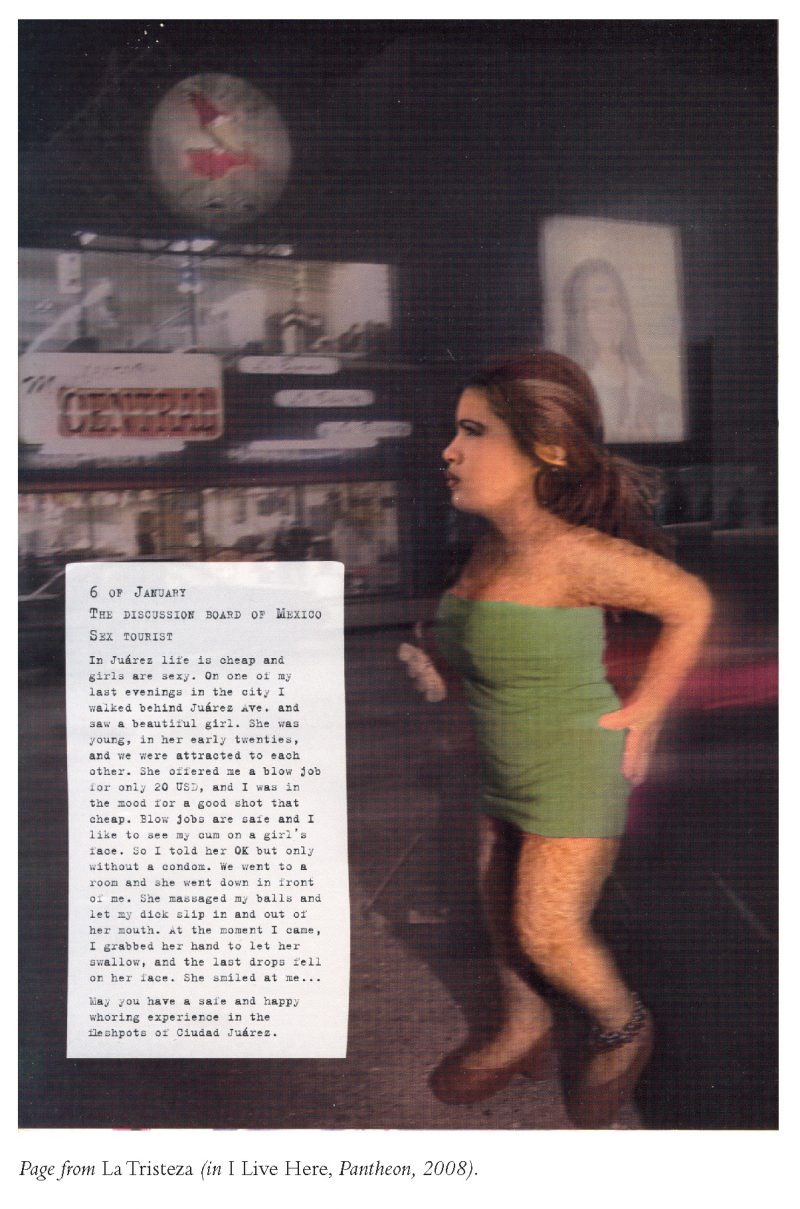

Gloeckner’s current project is another formally experimental take on young women’s lives, but it focuses on the murders of women in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Gloeckner first traveled to Juárez in 2003 to research her “graphic reportage,” La Tristeza, which was commissioned for the volume I Live Here, edited by the actress Mia Kirshner (Pantheon, 2008). Gloeckner started off drawing scenes of murder. She eventually developed a three-dimensional sculpting and modeling technique whereby she poses dolls that she creates—they are felted wool with wire armatures, and have styled hair and meticulously detailed clothes Gloeckner sews—in scenes in elaborate quarter-scale sets. She photographs them and then digitally integrates the doll faces with human features. The images are at once fascinating and highly unsettling. Currently an art professor at the University of Michigan, Gloeckner was inspired to embark upon a larger project focusing on the Juárez–El Paso border area. She has visited Juárez more than a dozen times in the past several years, and made close connections with the family of a murdered girl, Maria Elena Chávez Caldera, who remains the inspiration for her forthcoming book.

Our conversation took place in her Ann Arbor studio, where she builds and photographs her sets—and where her three-legged cat, Pipsqueak, hides out—for two days in December 2009. Gloeckner’s studio occupies the top floor of her house. We were frequently joined by her eleven-year-old daughter, Persephone, who improved my life by initiating me into the world of Twilight (Phoebe calmly sewed doll clothes as we screamed at the screen). I caught up with Gloeckner again in New York City at a performance of The Diary of a Teenage Girl, a new play adapted by Marielle Heller, who also stars as Minnie. Phoebe noted that she had seen the play four and half times already, and wasn’t sick of it. “Diane [Noomin, editor of Twisted Sisters] asked me tonight, how can you watch this? Don’t you feel destroyed? Because she was really affected by it. Every time I see it I forget that it’s my own reality, and to me it becomes someone else’s story that I’m experiencing.”

—Hillary Chute

I. “WHEN I WAS IN MY TWENTIES,

THAT WAS HOW PEOPLE RESPONDED

TO MY WORK, LIKE THEY THOUGHT

I WAS A SLUT OR SOMETHING.”

THE BELIEVER: In the introduction to A Child’s Life, you write about how you had this sense that no one would ever really see your work. You could do these “shameful” comics because no one would ever see them.

PHOEBE GLOECKNER: I was too young to be a hippie or anything. I read underground comics as a child because my mom had them. It was a weird period, because hippies were kind of out of style. I was getting into punk rock and it was like “dirty hippies” was one of the things you didn’t trust. Comics were kind of a hippie thing. And the underground comics were not as popular as they had been, and head shops were kind of closing, and they were the only places you could get underground comics. They were selling pipes and stuff and I would just go buy some comics. There were all these sex comics, and the guy behind the counter would always be looking at you like, “Oh, you’re going to get this comic, huh?” So it was weird, because none of my friends read comics like that, because they just weren’t popular to people our age, and they were obscure enough that they weren’t readily available, even in San Francisco, at that time, and it was way before [independent comics publisher] Fantagraphics or anything like that.

BLVR: Right.

PG: My mom started dating a cartoonist, and I knew Crumb, so I knew cartoonists, but they were a different generation. I equated them kind of more with my mom, you know?

BLVR: Did you always draw comics?

PG: I was always drawing. But doing comics was the first time I was doing some finished thing: you make a progression from just drawing to making a story—you’re writing as well, and it starts involving other faculties. Then I was [published] in a comic book. It was weird because I knew no one would see it that I knew, because no one read comics that I knew. I felt like I could do this in a bubble and still feel this sense of accomplishment. I wasn’t risking anything, because no one was going to see it, so I could do anything I wanted to.

BLVR: So then what happened with A Child’s Life coming out as a book? What changed?

PG: This publishing company came to me and wanted to see my portfolio for medical illustration, so I scheduled a meeting—it was North Atlantic Books. In the meantime they just mentioned that I was coming to somebody. And that person said, “Oh, Phoebe Gloeckner. She does really good comics.” And they didn’t know who I was. So when I got there they looked at the medical illustration, and the publisher says, “You know, we’ve been toying with the idea of getting into comics, maybe publishing something, and someone told us that you were a really good cartoonist.” And he said, “Would you be interested in publishing a book?” And I said, “Are you kidding me?”

BLVR: What do you think about your work being labeled obscene or pornographic?

PG: I think my work is not at all pornographic. I think that I’m just drawing life, and at the times where sex is important to depict, I depict it. I never felt at liberty to pick and choose anything else but what seemed important, and I don’t judge it, but I certainly have felt judged a million times. I guess I’ve become inured to it. I’ve been accused of doing things just to be provocative, which is bullshit. But one time this pornographer guy bought a painting from me, and it was a version of this image that is a cross-section of a blow job. I had done this painting for The Atrocity Exhibition. So I had a really large painting, and it was in color. So there’s this pornographer who used to employ cartoonists and stuff to do dirty comics. Screw magazine.

BLVR: Al Goldstein.

PG: Al Goldstein. Right. So he wanted to buy this painting. He took me out to dinner and then he was paying me and he said something to me like, “I don’t know whether you really like giving blow jobs or you really hate men,” and I don’t know what I said, but then, when he was paying me, he just gave me one hundred-dollar bill at a time, and he was paying me, like, three thousand dollars. I don’t think I’ve ever been paid that much for anything, and he did it one [bill] at a time so it was taking forever and everyone around us was staring, and he knew it. And then he goes, “Do you feel like a hooker? People think you’re a hooker.”

BLVR: He sounds so creepy!

PG: Well, it was kind of amusing. But in a way, especially when I was in my twenties, that was how people responded to my work, like they thought I was a slut or something, so I just kind of didn’t ever show people anything.

II. “AT ONE TIME GROWN-UPS READ BOOKS WITH PICTURES, RIGHT?”

BLVR: How have people in your family responded to your work?

PG: They don’t want to hear about it, and my mom… she can get real mean and real paranoid, and she threatened to sue me after A Child’s Life came out.

BLVR: I read an interview with her [“The Two Phoebes: Diary of an Artist and Her Mother,” in Metropole] and I was struck that her response, when she was asked about some of the things that happened in your adolescence, seemed fairly unsympathetic.

PG: She had terrible responses. I mean, nothing was ever her fault, and nothing is her fault, and she didn’t take responsibility for many, many things. What happened was that when I did tell her, she was angry at me, more than at [her boyfriend]…. I remember when I was really little, like, when I was five or six, I would look at her and feel like, “She doesn’t love me.” And I don’t know why I thought that. I just remember understanding that she doesn’t understand how to love, and luckily my grandparents—I really felt love from them, and I lived with them a lot.

BLVR: And she felt maligned by your work?

PG: You can’t worry about “What’s Mommy going to think?” when you’re writing a book. First of all, you have to distance yourself. Because you know even if it’s true somehow, you are totally fabricating this story. You have to put it on some narrative structure. You have to mix points of view and do all this shit, which in the end makes it something less than real and more than real. I mean, you are trying to make someone else experience something, and it’s artifice.

BLVR: Since you’re talking about aesthetic distance, one thing that’s so striking about your work is that there is a lot of formal inventiveness from work to work. The form of The Diary of a Teenage Girl is unbelievable. There’s the diary part, there are the one-page illustrations, and then there are the comics interludes, and then there are the bits and pieces of other comics. How did you come up with the structure?

PG: It was really hard, because, well, the trouble with my work, it’s true—I don’t like to repeat myself formally. I get really anxious and bored and I feel like I’ve hired myself to do something.

BLVR: That’s funny….

PG: Just imagine. You have this fucking diary. It’s burning a hole in your head. It’s sitting in your closet for twenty years. You want to do something with it. So then it becomes this precious thing. You don’t want to touch it, because it’s like “the words of the past,” you know? And so for a while I was trying to preserve it, yet thinking, This is not right. If somebody reads this, there are 40 million characters in it, and they’re not going to understand. You know, you suddenly see all these problems. It didn’t read as anything. So no one’s interested in your juvenilia just because it’s sitting there, you know, unprocessed. Who cares? So then I started thinking. You know, I love really old books. I have this edition of Émile Zola. Here it is [pulling old Zola book from shelf]. Anyway, it was twentyfive francs in Paris in one of those by-the-Seine bookstores. I love these books. Books for grown-ups always had pictures.

BLVR: The illustration is amazing.

PG: Yes, but the point is not the illustrations themselves, but rather at one time grown-ups read books with pictures, right? It’s interesting. So then I was thinking, OK, I love those books. I’ll just have single-page illustrations. And there are more than twenty in The Diary of a Teenage Girl. But the relationship of a single illustration to the text is just by nature redundant. It doesn’t really contribute to pushing the narrative forward. It might show you what somebody looks like, but you’ve already read about what that person looks like. It’s clarifying in a way, but it’s usually an interpretation of an author, because the author usually doesn’t draw the picture. It’s some sort of something that’s removed. And I was thinking, Well, in that case, these illustrations are kind of useless, and it was getting me mad. And then I was remembering all these other things that I wanted to be in the book that I thought were important. I wanted to do sections as comics to fill in the blanks without someone telling you what happened—more of an omnipotent point of view. You know, because with teenagers, it’s like, “Me, me, me, me.”

BLVR: There’s sort of a visual voice in the comics that almost seems to interject. It’s almost like the older self and the younger self having a conversation.

PG: The challenge was to make it seem somewhat seamless…. I wanted the comics not to feel inserted. I wanted the book to be read linearly. I mean, I guess people might skip to the comics. Lots of people complain there are too many words. But it didn’t bother me, because I wanted the words to be there, and then all the other stuff—it just had to be there, too.

BLVR: Right, and there are also floating illustrations, and the text goes around them.

PG: I had to learn how to put the book together myself as a designer. It probably would have looked better if somebody who was an experienced designer had done it, but my concern was that the reading had to flow, and things had to be on the right page in relation to the text. It was too much work for a designer to be working with me as I was doing the book…. Originally I had a designer and it drove her nuts.

III. LA TRISTEZA

BLVR: Since we’re talking about linear narratives and how to read, La Tristeza has such an interesting narrative form. Can you describe how you wanted someone to interact with that? Because it is really nonlinear.

PG: OK, so this is not a linear narrative. It’s not ever a linear narrative. I did this, and what is it about? I mean, it doesn’t even matter if it’s about Mexico. I think it was me responding to just the sheer number of people who were killed, and then trying to look at it individually. It was this thing struggling with having been kind of artificially placed there. The way it’s written… I mean, maybe you recognize it—you know, I didn’t speak Spanish, and so I was constantly looking on the web for more stories of what was happening, and then I would translate it in Google, and the language was so weird. It’s like that’s how I learned to think of Spanish, as not as Spanish, and not as English, but as this [other] language.

BLVR: That slightly messed-up, Google-translated language.

PG: But it also sounds to me kind of like a Victorian language. Certain prose in Victorian English. It reminded me always of some kind of stilted, slightly wrong sound. And I just grew to love that language. Some of the pieces of writing in La Tristeza are actual stories that I took from the papers, and then others were changed a bit, or rewritten, because I was grabbing stuff, you know. It was somehow working.

BLVR: Why did you decide to start making and using the dolls?

PG: I made a living doing medical illustration. You get hired for the same thing over and over again if you do it once. So I was drawing a lot of eyeballs, and drawing a lot of penises and sex-manual-type things. Illustration might be fun for a while, but then it gets kind of boring because there’s not that much variation. So I was doing this joy-of-sex-toys book [The Good Vibrations Guide to Sex] right at the time I went to Juárez, and they had sent me this huge box of sex toys, like whips and dildos, and things that light up, and butt plugs. They wanted me to draw them and do all this stuff. So anyway, I got back from Juárez, and I had all these police reports, and I just remember reading one about this girl who had slowly bled to death because they had raped her with a splintered two-by-four, anally. I didn’t like that thought of bleeding slowly to death after having something shoved up your ass. It just was not pleasant, and then I was drawing these pictures of these butt plugs, and the text was something like, “They come in this package of five, and they’re all different sizes, and what you can do is start with one, and have it up your butt for two hours.” I’m not even thinking about it judgmentally; I’m just drawing it. And making it look all soft and fuzzy. And then the directions were to increase the size of the butt plug, and even wear it to work, but why? I don’t know why, but anyway, because you want to, right? I was drawing that at the same time as I was reading this police report. I just started to feel like literally I was having a nervous breakdown. It was something about those two things. So I was trying to draw…. I felt like I had to draw the murders. I had to show the murders, because the girls experienced them. I couldn’t just not show it. And I kept trying to draw these things, and I wasn’t drawing from real life. You know, you have to imagine it, so your brain is kind of churning like, Oh, how does it look? And your brain is doing some kind of weird 3-D thing, like trying to get the picture, and I just started feeling like I was going to throw up. I really couldn’t do anything for a month. I couldn’t draw anymore. I couldn’t do that sex manual. I just felt like I was going crazy.

BLVR: What was it like trying to draw the murder scenes? You were saying that you had to have an image of it in your mind.

PG: I’ve seen a lot of surgery and dead people, but there’s some point where you kind of just cut off. You’re no longer empathetic to it, because you can’t be. You can’t really survive and feel it, but then sometimes you’ll have these flashes. It’s just like existentialism. Suddenly you realize you’re flesh. And those moments where you really realize what the experience is for the other person, it’s horrible. But you’re not conscious of it the whole time, because you can’t be. Your brain doesn’t let you be, so it’s terrible, and I guess the doll thing, I just—I felt like I was killing people by drawing them being killed, and I couldn’t do it.

BLVR: That’s so interesting—what do you mean?

PG: If you’re drawing someone being raped, you have to imagine raping them. You also have to imagine being raped. You also have to imagine your friend or your daughter being raped. You also have to imagine your brother raping somebody. All these things are in your head, and it’s like, “Who is it? Who does this? Why?” I guess if you’re writing or drawing it’s like you become all of the characters. Anyway, I always read photo-novellas, because you can learn a language that way, colloquially. You see what’s going on because you see the pictures. I thought, Well, I could just make one with dolls. It’d be really quick, and then it wouldn’t have to be in my head so long, and the dolls could be all bloody and die, and I don’t care, because then I could just wash them off, and they won’t be really dead. As if they would be alive. They wouldn’t be alive because they’re dolls, but it doesn’t matter. I was just trying to make it easier, so then I started experimenting with dolls.

BLVR: Had you ever done this kind of sculpting, three dimensional-type of work before?

PG: No. In the beginning, I wasn’t quite making that leap. I was not making the dolls de novo. But I didn’t like how they looked. And then when I got to the University of Michigan, they gave me fifteen thousand dollars start-up. So then I said, “Oh, I’m going to buy some power tools.”

IV. MARIA ELENA

BLVR: How did you decide to focus on one girl for the project about Juárez you’re working on now?

PG: When I first went down there, we met all these families of girls who had been murdered, and it was really hard for me. My older daughter at that time was a young teenager, and I was thinking, All these other girls were that age, and so you can’t help but relate immediately to these mothers who are bursting into tears. And besides that there was just this incredible poverty. Some of the families were so poor that we were sitting in the house. There’s this dirt floor. There’s no plumbing. There’s no water. There’s electricity tapped from some wire someplace, and there’s a sandstorm blowing wind, so you can’t go outside, and the wind is coming right through the house, because it’s just discarded wood with cardboard tacked on the other side, like old boxes, and they had lived there for, like, ten years. It’s like nothing improves. At the most I had thirty pages to do the story, and I felt like I couldn’t possibly address all the things I was thinking and feeling in those pages. And so I decided that I was going to do something longer. I don’t want to do that kind of short thing—encapsulate life. You have a little slice of life of this poor suffering person and you feel like you know everything, but nothing ever happens. Nothing comes of it. I wanted to go back to Juárez. I wanted to really somehow be a lot closer to it than I was. The separation really bothered me. And I decided to focus on this one girl for the longer story. The reason I chose her was because we had met a lot of people, and a lot of families, and most of them came and showed us pictures of their kid. They would save newspaper clippings talking about when she was missing, and some of them even had videos and things, and lots of things to tell, stories to tell, report cards, everything. And this one girl, her parents had nothing. They had no picture of her, not one picture, and then finally her mother said, “Well, we do have one picture, but the police took it to make the missing poster, and they didn’t give it back to us.” So the only picture they had of her says missing right across her forehead. It was a Xerox copy.

BLVR: That’s so heartbreaking.

PG: They didn’t save any of her stuff. I mean, they had twelve people living in one room, and, you know, they might always live almost that way

V. “I WOULD JUST THROW THE TRASH ON THE FLOOR”

BLVR: Will you explain your procedure of working with the dolls and the sets that is part of both of your Juárez projects?

PG: So you see this floor? It’s canvas with glue and sand mixed up and put on there. This has changed around a hundred times. I used to have loose sand everywhere, and then I was building little houses, but the cat started shitting in the sand, so then I had to glue the sand. I would come up here and there would be sand on the floor, and every time I had some trash I would never think about throwing it in the trash can. I would just throw the trash on the floor. Because in Juárez, it’s like there’s trash everywhere, and because on the outskirts they never have trash collection, and the sand covers it, and the wind blows and the trash is exposed, and it’s all over the place. So I was trying to cultivate bunches of trash. This guy [picking up male doll inside a constructed set]. He’s a bad guy. You don’t see it, but he’s got a big dick in here with a wire in it, because he raped somebody, and I don’t know if I’m going to show that scene or not, but it has got to be there. Just because I know it’s there it makes him more threatening. I don’t have to be rude and show you his dick.

BLVR: What? You were talking about it.

PG: OK, let’s see it. It’s not that big, but it’s just there. There’s the little balls underneath it. And some of the dolls have vaginas so they can be raped.

BLVR: So you had to teach yourself how to sew—not only the clothes, but the bodies, too. The hair is complicated. Everybody has specific, different hair….

PG: I didn’t know how to sew at all. Hairdos—I mean, that’s kind of fun.

BLVR: Where do the photographic faces in your work come from?

PG: I use my face sometimes. I’m superimposing things, but there’s a lot of distortion involved. It ends up looking on the doll like maybe it’s not so distorted, but I try to make it so that it’s conformed to the face of the doll.

BLVR: So you set up the scene, you pose the doll, and then you have this photograph, and then how do you actually get the final image?

PG: OK. Let me show you [opening up image files on the studio computer]. I don’t love this picture, but I’m working on what [Maria Elena’s] boss is going to look like. The guy whose house she cleaned.

BLVR: What’s his name?

PG: His name is Hector. So I was working on his face. So this is going to be his face, what it is going to look like. You know in Photoshop, you can keep the layers intact. That’s Arthur, my husband, and so he’s playing that role, but I distorted his face.

BLVR: This is exactly what I wasn’t understanding before.

PG: I put his hair in a headband so it’s back. It’s an ugly picture, a terrible picture. Not flattering. I was telling him what to do, and he’ll very nicely do it. But then his face is too long and narrow and I don’t want it like that, so I made it wider and then I started blending things, distorting them, and actually… Oh, look at that. I was putting cataracts in his eyes. So I’m just adding things there at that point to make it look more like this old man. Hector’s mouth is much bigger and his eyes are smaller and his chin is beadier and I distorted the color to match the dolls more. It’s not quite done yet. You can see it because it’s not quite blended into the doll, and the hair’s not done or anything. But this is just an example: OK, so what’s this character going to look like and is Arthur the right person to be that? How much am I going to have to fuck with his face to get it to be like I want it to be? It’s not something that is just automatically put in.

BLVR: Right, you don’t just slap the face onto the body in the program.

PG: Right, you wish! You have to make it look like it’s integral to the image. It’s not quite there yet, but I think he looks like this asshole I want him to be. And if the faces are not distorted, it doesn’t look good, because the image doesn’t have that kind of unreal thing. I don’t know if it’s always obvious that they’re changed, but they’re changed a lot. Like sometimes I even use eyes from one person, and a nose from another person.

VI. “HOW MANY LIVES ARE AFFECTED BY ANY ONE MURDER?”

BLVR: So what is the form of the book ultimately going to be?

PG: Well, it’s like The Diary of a Teenage Girl. I have all this stuff. And I’m still struggling with the final form because I’m doing some animation.

BLVR: So it’s going to be a printed book, but there’s animation, too?

PG: I have a Kindle. I got it when it first came out. I’m fascinated with how books are going to be, because I really think they’re going to be different. Just face it. But the machines to see the books are not quite right for what I want to do. In the book, it might be that you would have a couple pages of text and one picture, and then, you know, maybe it’s just a picture, but as you’re turning the page, you see someone move a little bit. Are they still alive? And then maybe you could, like, pet their face and it goes into the scene of what just happened, or it’s animated. The Diary of a Teenage Girl has these different elements visually. But this new project cannot be a book with a CD. No one would look at that. It would have to be something as seamless as possible, but not a film, because what I like about the [form of the] book, however it is, is that you control it when you’re reading it.

BLVR: I think that’s key, especially with a work as traumatic as this is.

PG: Yes, and I just don’t want to tie it up neatly and end it. And also the words are important to me. In a film it’s like you no longer have control of that. You don’t focus on words in the same way.

BLVR: Yes, I mean, it’s in time in the sense that you just sort of cede to the film….

PG: I want some element of time in this, but I want to mix it up in my own terms. I want to control it. I don’t know if I would be able to do this. I’m thinking not, although I have all these elements, and I continue to work. Next month I’m working with these people to do this kind of animation where I have my actor and the dolls. That’s why I’m working on these new armatures, because I want to get a doll that moves better, so that they can be keyed together, like the doll will have points on it, but they’ll digitally align to points on this person’s face, so we can get it in real time more easily, and have the dolls animated, but the face will be following, you know?

BLVR: So the face will be a human face, in the vision of the final product, but it will still be the doll moving. The doll body moving with the human face.

PG: Right, so it will be a similar effect. Most likely I’m not going to find anyone who would be able to do with it what I want to do. I mean, companies are coming out with better interfaces for books, but ideally… I think they should make a Kindle or whatever it’s going to be called, with something you can turn, and I don’t know exactly what I’m talking about, or how they would do it. But I think when you’re making a book, especially a comic book, you actually use this element of surprise. I want for someone to be able to scroll through the whole thing, and there would be a half page, or a full page. I want to be able to use the relationship of pages to each other intentionally, one way or another, to work for the story. In the Kindle right now, it does have virtual pages, but you don’t have two pages together, although you could. I guess there are other ways to get around it, but it just seems like those electronic books have a ways to go before you can do what I want to do with it.

BLVR: So you’ll have the images with the dolls, and text, and animation—what are some of the other parts of the narrative?

PG: I have this whole other part of the project that is going to be shot as a photo-novella. The murdered girl’s sister, Brenda, is part of that. She was thirteen when her sister was murdered. Now she’s about twenty, and she has three kids, and a totally different life.

BLVR: Did she mind doing these reenactments, based on things that actually happened?

PG: These are not based on real things. It’s kind of like a foil to the story, because when you read Spanish comics, or ones in English, or the photo-novellas, they’re all really dramatic. Or the things on TV. I watch Spanish TV all the time. Everyone is beautiful, and everyone is cheating or loving or something. It was hard to get Brenda to be real dramatic. She was laughing, saying, “Why am I doing this?” But it will work in the end. You have to idealize it because that’s what’s done and that’s what feels right, because I’m not making fun of her. I’m making her la romantica. But all these stories that feed into it are part of the confusion, because when you look at Juárez, you look at, OK, what? By the end of the year, it will be, like, twentyfive or twenty-six hundred people who have been killed. That’s a hell of a lot of people. None of these murders are solved. How many lives does that represent? If you kill a person, you know she has a family. She has this [pointing to pictures of Brenda]. How many lives are affected by any one murder? And there are all these stories, and there are all these stories that contradict other stories. It’s just a whole city of stories. What happened to this person or that person? So it’s like this story is just yet another story, and it adds to the confusion, but also it adds to the clarity in that it creates this ocean of story, really. It’s what it feels like to me there, because there are no answers.

BLVR: Do you see this work as connected to your first two books?

PG: I see it as really connected. Working on it feels very similar, even though it looks very different. My relationship to the detail is that thing which is both distracting and essential. And I’m always doing it whether someone wants me to or not; I feel like I have to do it. I’m always taking pictures. I’m always doing this, but what I’m going to make of it is another question. What’s important to me about my work, or doing whatever I do, is that I just want to know: What is it to be alive? What is it?

BLVR: But what’s so interesting is that it seems like this work in part is about you trying to figure out what it’s like to be dead, too.

PG: Oh, it is, yeah.

BLVR: There’s also a certain flinch-lessness. That’s not even a word, but you don’t seem to flinch delving into the past.

PG: No, I don’t. I feel like I’m really lucky, because I can create pictures. It’s not giving me any real power, but it feels like power. I feel like I’m making a world. Even if it’s a picture I’m using off some newspaper, I make it so it’s mine. I don’t know what that means, but I guess for me it’s necessary because any world that you’re making in a story, you kind of have to live in it.