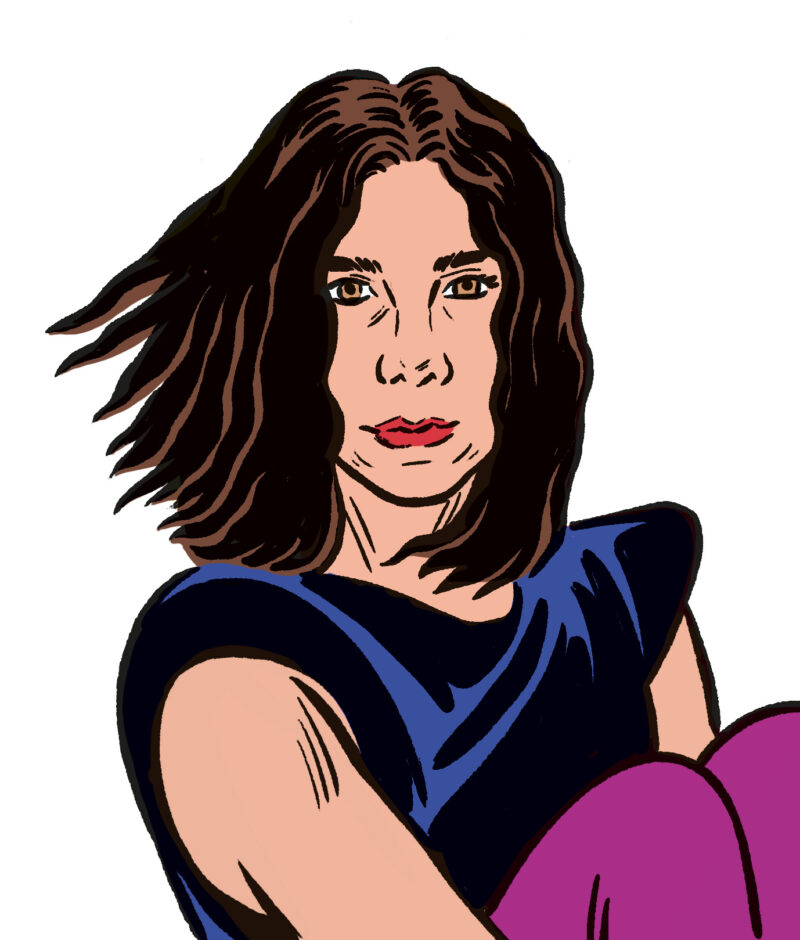

Polly Jean Harvey is an artist in a constant state of evolution. Those who signed up for the PJ Harvey Fan Club after hearing 1992’s volcanic album Dry have happily gone along for the ride as she tries on new styles (music, clothes) and new moods (raucous, melancholic, ecstatic). Few artists can hold on to a devoted fan base no matter whether they are fashioning a folk tale (1995’s “Down by the Water”), embracing full-throated politics (2011’s Let England Shake), or playing the hurdy-gurdy (2016’s The Hope Six Demolition Project). This last effort was a vast multimedia project that included an album recorded behind one-way glass in Somerset House in London, as the public looked on, and was followed by a volume of poems, a collection of photographs, and a Seamus Murphy–directed film, A Dog Called Money, which documented the making of the record. It was a leveling up, but also just another stepping stone for the enigmatic artist in her continual reinvention, in which she somehow always stays just so fucking cool.

What’s clear, though, is that her creativity cannot be contained in one medium. In addition to her ten studio albums, she crafted the score for the series Bad Sisters, and her songs were heavily featured on the soundtrack for the second season of Peaky Blinders. She’s published two books of poetry: 2015’s The Hollow of the Hand and 2022’s Orlam, an ambitious book-length poem written after studying with Scottish poet Don Paterson and learning the dialect of her home county. Dorset is located on the coast of England, and is not only where Harvey grew up and currently resides, but also home to the nineteenth-century poet William Barnes, who wrote in the Dorset dialect and inspired Orlam. The not exactly autobiographical poem is set there, albeit in an imaginary village called Underwhelem. It follows nine-year-old Ira-Abel and her guardian, Orlam, an all-seeing lamb’s eyeball. Despite its strangeness, it is a surprisingly relatable and absorbing volume. Harvey doesn’t seem quite ready to leave that place behind. Her 2023 album, I Inside the Old Year Dying, takes listeners deeper into the world of Orlam while simultaneously exploring intimate landscapes and enormous topics like love and connection. We chatted via Zoom (camera off) about music, language, ghosts, and the correct order for cream and jam on scones.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in