Raymond Pettibon raises dogs. Pitbulls and mastiffs mostly. They live in breeding sheds and kennels in his backyard. Some are “sporting” dogs that he trains and fights in and around Southern California and Mexico. One is a full brother to Bain, a former Yojimbo in the world of dog fighting, the sport of kings. Mention Bain to anyone in the dog-fighting business, Pettibon tells me, and, well, you get this certain look.

Pettibon unloads all of this in the middle of a conversation ranging from punk-rock history to horse pedigrees to comic books to art criticism. On the subject of dogs he suddenly seems to feel like he’s revealed way more than he intended. So he drops it. This is the way with Pettibon. In his pogo-ing from topic to topic he is both excessively careful with his words and bluntly indiscreet. It’s a quality that also comes across in his drawings.

Born in Tucson, Arizona, and raised in Hermosa Beach, California, Pettibon sacrificed a career as a public-school math teacher for a desperate, thankless existence as an internationally exhibited artist and dog fighter. His art career began in the mid-1970s when his brother Greg, a guitarist for the seminal punk band Black Flag, founded SST Records. Pettibon became the label’s unofficial artist, creating album covers and concert flyers for Black Flag, the Minutemen, and others. His style—a pairing of figurative drawings and text done in black ink on paper—is often associated with the seventies punk counterculture of his youth. But Pettibon will tell you that’s a brainless oversimplification.

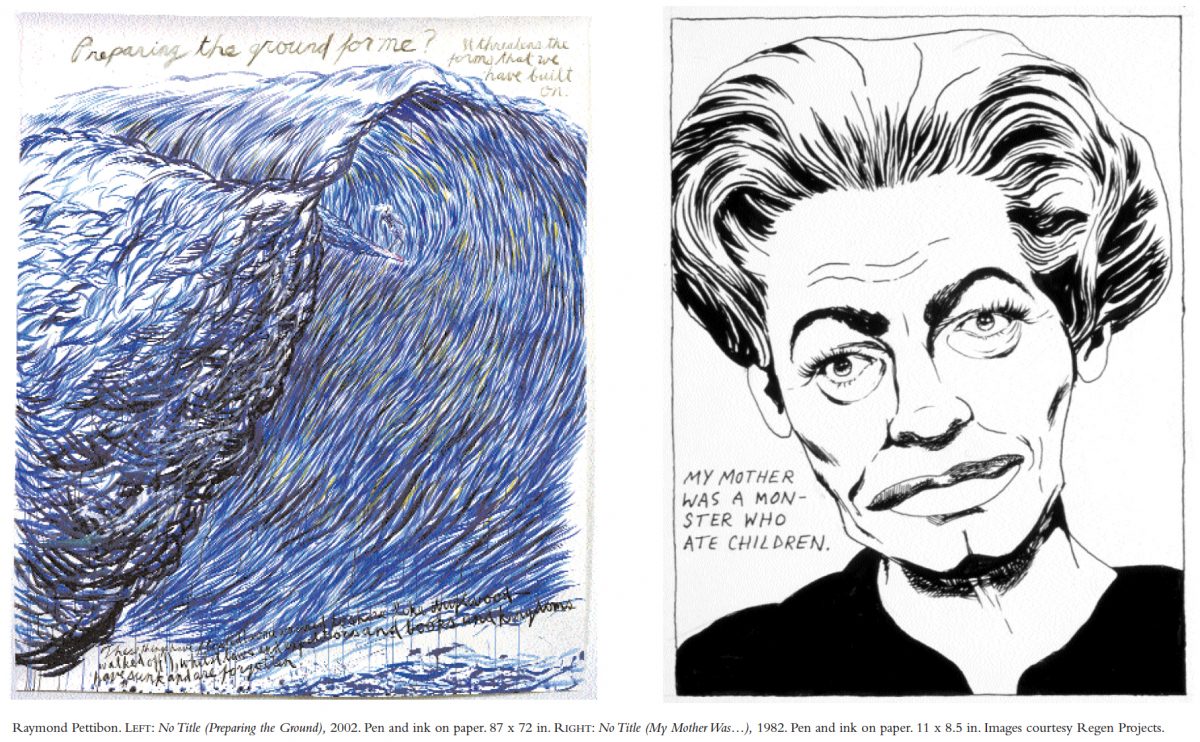

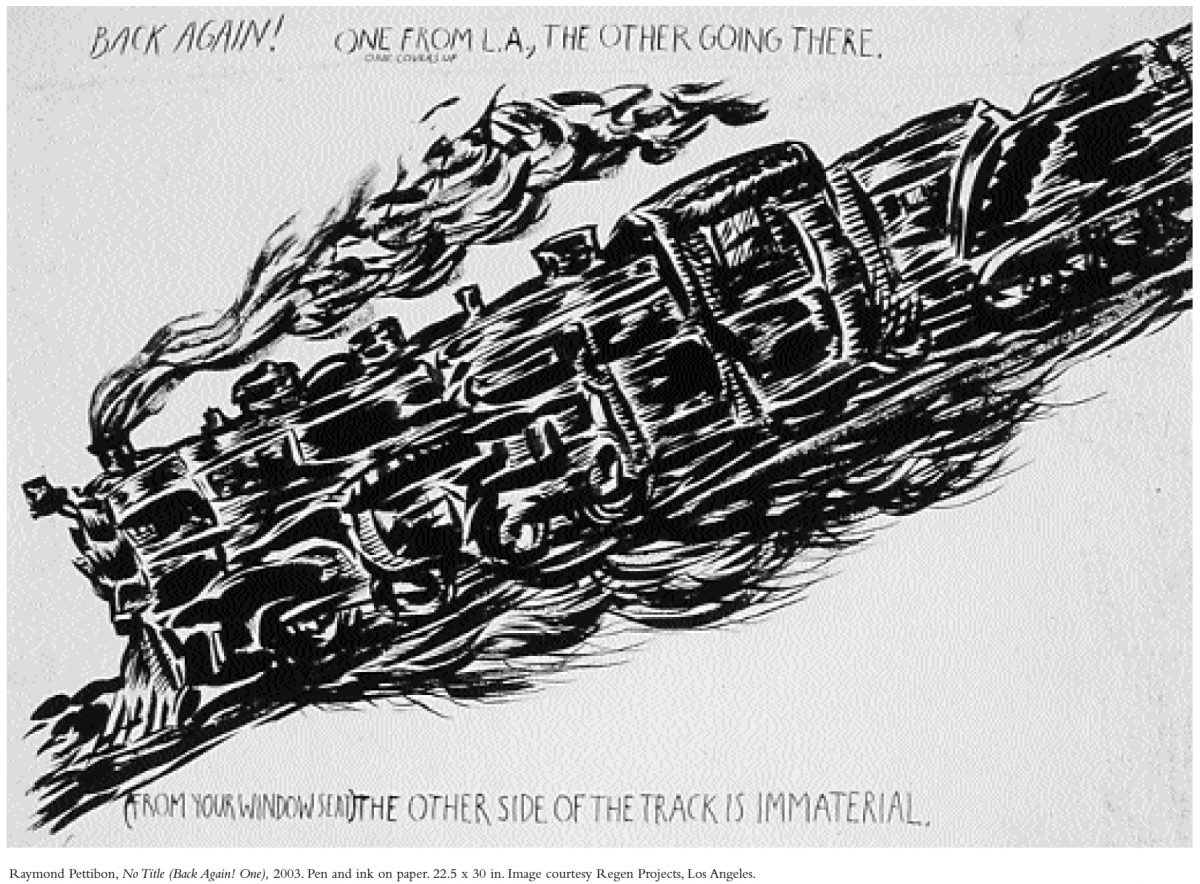

Though he vigorously resists attempts to categorize his art, Pettibon acknowledges a debt to various sources of inspiration: comics, noir films, books, television, pop icons. His work can sometimes seem like a cataloging of pop-cultural moments. Charles Manson, Ronald Reagan, and other broken, twisted speed freaks figure prominently, as do punks, surfers, hippies, baseball players, locomotives, and Gumby. Whole phrases are lifted directly from books—Henry James, Fernando Pessoa, William Blake, the Bible—or are reshaped and given new meaning by the artist.

Despite this, Pettibon’s art is also deeply personal. Each drawing seems oddly idiosyncratic, almost painfully revealing. Individually, each is like a snapshot of a larger narrative.

The following interview was culled from a couple of marathon phone conversations with Pettibon from his home in Long Beach.

—John O’Connor

I. “COMICS ARE OFTEN DISMISSED OUT-OF-HAND AS BEING WORTHLESS,

OR FOR CHILDREN ONLY, OR EVEN HARMFUL TO CHILDREN.”

THE BELIEVER: To what extent did your art come out of the punk scene?

RAYMOND PETTIBON: The art preceded punk. I don’t know if it’s really possible to trace back and see if there’s a progression, a timeline, in any coherent sense, to my style. I wanted to retain the writing and representation, the figurative imagery, the people and places from that time, and to do that within my own means and talents and capabilities. That lead me into an illustrative-comic style, which I think is useful for what I do. And I retain that to this day. But my drawing also came out of editorial-style cartoons I was doing at the time. Music was one thing and art was another, and there weren’t really any standards for my art. If you look at old punk album covers they were mainly Russian constructivist or Heartsfield collages. There was no defined punk look or style. Not in art at least. Maybe in fashion. My work was just drawings, and basically drawings just as I would do now. They weren’t done with any aspirations of becoming a part of that scene. They weren’t about punk. They were just collections of drawings, some of which I xeroxed and sold. But you couldn’t even say they were sold in the punk scene. That would be a tough audience to crack. I would sell them to anyone I could. But it was never my goal to capitalize on punk. I could never make it as a commercial artist. I didn’t back then and I still don’t have the temperament and don’t care for drawing or painting or making art for any other purposes other my own. I’d rather do anything than make commercial art. I didn’t go to school for art. Making art has certain advantages for me but they would never be in that direction.

BLVR: What sorts of advantages?

RP: It’s an extreme to go from an artist like myself to a commercial artist with art directors looking over your shoulder, or any other knucklehead telling you what your art should look like. Everybody has his own great ideas about what it should be. I can do whatever I like and there aren’t many constraints to the way I work, whether I’m using a brush with ink or paint. Now, I know my art isn’t made in a vacuum. I’m not God, but I’m working within my own means as an artist and a person, and I possibly have more power than God does, in whatever form he has, if he exists, because I can work without the overarching ambition of wanting to rule over everything. I can work just for the heck of it.

In other words, I don’t make art with grandiose delusions. I do know there are limits to what art is capable of. That makes it all the more appealing to me. And I can do as I will whenever I choose. Someone like that, as compared to a commercial artist, is going to make his own time of it and do exactly what he wants. I’m still learning, but not because I didn’t go to art school. The rudiments of picture making aren’t really taught there anyway.

BLVR: You said you have an illustrative-comic style. Comics and cartoons have obviously had a big influence on you, but your work is also different from both. How do you see your art as distinct from traditional comics?

RP: I wouldn’t want to be defined so much by comics or cartoons. My work is more narrative than that. If you take your basic cartoon, there’s always a punchline or a joke at the end. My drawings don’t depend on that so much. Though recently I’ve done some work that has multiple panels in a comic-book style, and that form has a lot of appeal for someone like me. It tends to get dismissed because of the quality of the bulk of the work that is done, which is something that most art forms have to go through. But there’s no inherent reason why you can’t do something with the form. And that’s not to say that something of quality hasn’t been done with it already.

BLVR: It seems like comic artists are getting more mainstream attention these days than ever before, and drawers are starting to be considered “legitimate” artists, in the same realm as painters or sculptors. Do you have any theories about why that is?

RP: They should get attention. But I don’t think it’s because the drawing has gotten any better. You look at someone like George Herriman and Krazy Kat and you see better work than in just about anything that’s done today. I think it’s audience more than anything. The audience is growing. The problem with comics is that there’s a million of them, and there’s this whole tradition behind it, so that the creators are all aspiring to become professionals in the mold of their heroes. There are people who can tell you in detail beyond belief everything that ever happened in Superman’s universe. Now, that’s fine. But it’s for a really particular audience of juvenile interest. That’s not to say they’re all bad either. Comics are often dismissed out of hand for that reason, as being worthless, or for children only, or even harmful to children. That’s not what I mean. I think it’s amazing that there are all of these new people finally taking this form seriously and properly, as it should be. But even when I was a kid I just couldn’t read comics, and it wasn’t because I looked down on them. It’s just that you really have to become emotionally and intellectually involved in them, if not challenged by the whole universe they create. Without trying to sound dismissive, it’s just not what I’m trying do.

BLVR: I’m surprised you didn’t read comics as a kid.

RP: Don’t get me wrong. I was very influenced by them. The drawing style, definitely, I was interested in. My style of drawing is largely a comic style, but it’s also much more obvious than comics. In the sixties, to do anything in art that had recognizable figures in it was considered an attempt to have the work draw attention to itself. Lichtenstein did it with benday dots and dialog balloons. It drew so much attention to itself, it was so perverse, that it became begrudgingly accepted. That’s not meant as a putdown of him. But there should never be any apologies in art, or any overt attention-drawing in that way. What I felt I was doing was making my work as transparent as possible, without equivocations, without calling attention to itself, without apology. There’s a lot of conventions in the art world that are not to be transgressed, but my economy of means doesn’t abide by those strictures. There’s no reason to abide by them. I don’t have any vested interest in it.

BLVR: Do you see yourself as a progenitor of today’s comic artists?

RP: No. I hear that, but I just don’t see it. That’s like saying I invented the comic style. This is something that was already there that I adapted and borrowed. I really don’t see any influence of my work on any artists. But I do think I’ve had an influence on drawings’ being shown. I’ve had an influence on the economics of it. To what degree I can’t say, because there are others who have been just as influential, but I think there are more drawing shows now than there otherwise would be, and there’s more acceptance of it.

II. “I DON’T WANT TO EXPRESS VIOLENCE OR ANGER

OR HATE IN MY ART. I WANT TO EXPRESS FORGIVENESS.”

BLVR: Books have also had a big influence on your art, and you’ve said that sometimes it’s not just a matter of editing the lines you put in but that the lines themselves become your context. Can you explain?

RP: I think that was in reference to my drawings where the lines are actually cut out from the text and put in, although it doesn’t have to be. The distinction is hardly there. There are instances where lines in my work are borrowed or stolen from sources, mainly from books, or they become my own versions. A lot of the writing is my own, too. But if someone were to take each drawing and trace it back to its source, most of them could be traced back to a book or a text.

BLVR: You’ve also said that while you’re working the drawing seems like a chore and what you like best is the writing. Has that always been the case?

RP: Yeah, definitely. I think I always enjoy the writing more. If you saw every show or every book I’ve been in—and this is coming from someone who’s considered to have produced a gratuitous amount of work—you would see what I mean. But drawing is also one of my favorite things to do.

BLVR: Do you start a picture with drawing or with writing?

RP: There’s no set formula. Though I guess nowadays I tend to start with the drawing. At first, for some years, I didn’t at all. It was always the idea that came first, and the idea had the visual concept to it, and that’s when I came in and did the drawing. Now it’s a combination of the two.

BLVR: Who are some of your literary influences?

RP: If I was going to do any favors for someone who’s interested in the extent of my borrowing, I’d say, and this doesn’t necessarily mean these are my favorite writers, but Henry James would be the most obvious, both his fiction and letters. Also, right now I’ve been reading Emily Dickinson’s letters, though I don’t think I’ve borrowed anything from her poetry. Not yet anyway. Thomas Browne, too, and Ruskin. I borrow from noir, but that’s mostly visual. Mickey Spillane is an interesting writer in a way. His directness. Come to think of it, he started in comics, which figures. Again, I don’t mean that in a bad way. He was just so over-the-top and black and white with no shades in between. Today he could be writing for Commentary or Public Interest. But visually, noir was a big influence on me and still is.

There was a period when I was getting a lot of my images from television. And this might be disappointing to my fans, like, now the visual universe is phony, too, but I had this video recorder for a long time that took still images from television. They lasted five seconds, and I would take images from Peter Gunn and noir films of the thirties, forties, and fifties. If you look at TV in that way it’s almost always a shot of talking heads. The only interesting visual compositions are of some kind of violence, with guns and fists and bodies. It’s always one extreme or another. So it was less because I had some abiding interest in violence or gangsters, and more because that was what was visually interesting. And you could say that about any of my imagery, really. There’s not much of an emotional involvement or commitment to it. And that’s really saying something, because it’s those couple of years back then, with that recorder on my TV, that I’ll be paying for for the rest of my life. Once things hit the critical discourse they stay there and they replicate like viruses until they take over the artist. Seriously. Some artists go with that and become what they’ve been made to be. Some fight it and retool and redefine themselves. I don’t consciously do either. But that’s still going to be the first thing people think about me, whether they’ve actually seen the work or not. That’s not a major complaint. But it’s like with the punk thing: yes, I think it was very important in music, and I was there and all that, but now I’m going to be the punk artist for the rest of my life. Which is kind of amusing, and a comment on the press and the critics.

BLVR: People seem to like categorizing you.

RP: Yeah. It’s funny, because there isn’t such a thing as a close reading in the art world anymore. There used to be. There was a time when there would be a close reading of a painting or a sculpture to an almost parodic or ridiculous extent, but not anymore. I don’t mean to sound dismissive of the press, or to give you some anticritic diatribe. For the most part I think the level of writing in art is very high.

BLVR: But is it fair to say that noirish themes—depraved sexuality, violence, self-loathing, booze-addled women—run through your art?

RP: Well, yeah, there’s that interpretation. But as I said, that really has more to do with the formulaic qualities, the compositions, in noir. Personally, I don’t like violence and blood. I turn my head at anything like that. The thing is, there can be more interest in that sort of thing for me, and for many people, in works of art. Just the action of it, the violence inferred, tends to get a certain reaction that’s more interesting. On the other hand, I’m not Pollyannaish about it. I’m for opening the prisons.

BLVR: Do you think of your art as overtly sinister or morbid, or does it have more to do with hope and redemption? I don’t mean that in a biblical way.

RP: I don’t know if it goes that far in either direction, really, or begins or even ends there. I believe in redemption, sure, as much as we have it on earth. For the record, I don’t believe in any spiritual redemption. But my work is much more complicated than redemption or no redemption. I do feel it’s dangerous, both on a personal and a political level, to be anything other than forgiving. The stakes are just too high nowadays. I don’t want to express violence or anger or hate in my art. I want to express forgiveness. That’s the nature of my art in general. It’s expressing love and compassion, the kinds of things that don’t make sense in any other context other than emotive expression.

BLVR: Some of your drawings—and I’m thinking of works like the one of the pistol with the caption “My bout with depression lasted five chambers,” or of the old woman with the words “My mother was a monster who ate children”—have a sinister quality, or maybe it’s just dark humor. In any case, there’s this disjuncture between the drawings and the text that adds a lot of humor.

RP: That’s true for the most part. Usually it’s because the image and the text are at such a complete disjuncture from each other, or unrelated, almost random, so that one has nothing whatsoever to do with the other. But I don’t know how much I can say that’s conscious on my part. I’ve never been good at planning or directing my work towards specific things. Also, these sorts of things tend to get internalized to the point where they become second nature. It’s a technique for setting up conflict and resolution, perhaps, but I’m not filling in punch lines, like with cartoons. Eisenstein’s stuff was all about that clash of images, with montages and snippets of this and that. But that can become trite if it’s taken too far.

BLVR: Some of your drawings are much more “accomplished”—for lack of a better word—than others. Is that a stylistic thing related to the content of your drawings? Do you deliberately under-draw sometimes?

RP: No, I don’t think I usually do. Unless, maybe occasionally, if it’s for a certain affect in an individual drawing. I don’t know how often that occurs, but not often. But otherwise, no, I don’t try to under-draw. You might be thinking of earlier drawings. Some of my work can impress you as being from another person altogether. And in a sense it is. I have a tendency to think that some of my early work is better than anyone could have expected from me then, or even now. I think, if anything, for a while now my work is getting way too—I don’t know, it’s losing some of the best things that drawing has to offer, which is its easy facility and its ability to depict things with a few strokes of the brush without laboring over it and trying this and that, scraping, painting over. It’s not getting better. To its detriment, in fact, it’s losing something. And sometimes I sort of wish I could get back to the earlier drawing. But I don’t think that’s possible. It’s possible to try, but I think it would end up looking the way an artist’s work inevitably looks when he goes back to children’s drawings.

BLVR: Why do you think that is?

RP: I don’t know. I don’t know what it’s telling me. I’m missing the message.

BLVR: Do you think your creative process is becoming more deliberate as you get older?

RP: I don’t know. You can become too close to it while you’re doing it to have that remove from critical acuity. It’s like when I go out on the dance floor and the whole floor clears and everyone’s watching. I don’t know how I’m doing. I guess good. Maybe not. I’m joking, but what I’m saying is, it’s the same effect.

BLVR: So it’s about your audience’s response?

RP: Yeah, it’s about response, and the reaction shots before and after. But I’m pretty much on my own as far as audience goes, because my community of fans—I’m not sure if it even properly exists.

III. “I DO ACTUALLY LIKE BASEBALL

AND SURFING AND GUMBY.”

BLVR: The reoccurring subjects in your work—surfers, trains, ships, baseball players, people like Charles Manson and Elvis—what do some of these represent to you?

RP: I don’t think I’ve ever done an image that was meant to be reoccurring in the beginning. What happens is that after drawing one you can’t leave them. They have more to say to you. In a way it can take on a life of its own. I guess people probably think that these are images that only an excessive relationship leads one to doing, like fifty Gumby or Manson drawings. But it’s not like that. I do actually like baseball and surfing and Gumby. Manson, I’m not a big fan of some things about him, but there are some other things that are interesting. I’m not making a case for anything he did. But as a subject matter, on paper, there’s something to it, there’s something to write about there. There are certain figures, without even my meaning to do it, that become subjects. Whether it’s people or trains. Sometimes it’s more the visual nature of the subject that leads me to it. Visually they can be obstacles to try to overcome. But for whatever reason, they don’t start as serial projects. Otherwise I would have done them from the beginning. It’s always been after the fact.

BLVR: With writing and drawing, does one bring out the other for you?

RP: It’s not that exact, as if I dream in images and my waking thoughts are in text, or as if my daydreams become my captions and illustrations. I don’t know if it’s good to separate the two too much actually. But yeah, one depends on the other. There’s always a latent or inferred image in my writing. And I can almost always assume if I do a drawing that it will eventually have text. Now, I can only take this so far, because it’s almost starting to sound like an apology for writing, as if it’s this impurity imposed on the visual image. In art, impurity is not a mortal sin. You have to navigate through it. I say that only because there’s not too many of my drawings that don’t have text. There are some, but not many. If I were doing cartoons it would be a lot easier.

BLVR: You won the Bucksbaum Award this year at the Whitney Biennial, which is “awarded to an artist who possesses the potential to have a lasting effect on the history of American art.” Do you consider yourself a representative figure in American art?

RP: Is there a developing consensus that I’m not? That the award was unjustified? [Laughing] I know they want me to return it. I’ve heard rumors that they made a mistake and the whole thing was a terrible misunderstanding. They’re apologetic about it. But I told them the money’s gone. I spent it all at the track.

BLVR: Dogs or horses?

RP: We don’t have dogs in California anymore. It’s a licensing thing, government payoffs, special interests. It’s just horses now. But I raise dogs for fighting.

BLVR: Isn’t that illegal?

RP: Yeah, but in L.A. everything’s illegal. Even breathing.

BLVR: We’re talking blood sport, right?

RP: Well, listen, I train them and I fight them. It’s not a big deal, and it’s not something I like to talk about, really. I also have a charity where I give dogs to underprivileged kids. Not everyone can afford to buy a dog, and it gives kids the opportunity to attain a certain level of responsibility.

IV. “WITH CRITICISM IT’S NEVER JUST BETWEEN THE CRITIC

AND THE ARTIST, OR BETWEEN THE CRITIC AND THE CURATOR—

IT’S BETWEEN THE LIVING AND THE DEAD.”

BLVR: Which brings us full circle—does the Whitney award feel like pressure?

RP: No, it’s all an abstraction, even the money. Well, when you’re filthy rich it’s unfair to say it’s just an abstraction. That’s rubbing it in a bit. But I don’t take it as pressure. I say that without trying to seem like I’m taking it in this ho-hum way, like the award doesn’t matter to me. I really appreciate and am humbled by the award, by any award, really. I’ve only won two in my life, but they were both for a hundred grand, so don’t feel too bad for me.

BLVR: I think I read only one good review of the Biennial.

RP: There are never good reviews. But I think this year it was generally more positive than it’s been for a long time. It’s funny because according to the critics every Biennial, every Documenta, every Biennale, every show of that sort that happens every two years is always bad. In everything that’s been written about the Whitney show I don’t think there’s ever been anything positive said. Sometimes they’ll like one artist—and this was probably true with me this year—and usually it’s someone who’s past his prime, because you need someone to compare everyone else to.

These poor critics, as if they ever actually go and see the shows anyway. It’s like you’re affecting their health or their sanity by forcing them to see it. And that says something about the state of art today. The world would be a better place if they hadn’t written as much as they did. I’m kind of thinking out loud as I go along here, which in an interview is dangerous. A lot of artists have their publicists do these for them. Sinatra did. I should do that.

BLVR: The critics love to hate certain big shows.

RP: You know what it is? It’s because it hits too close to home for them. The critic and the curator are natural enemies. Critics think anyone who has the nerve to curate a show of the magnitude of the Biennial is too big for his britches. And critics and curators are too close to each other. It’s one of the few instances in the art world where there is some transgressing of the strictly demarcated boundaries between critic and curator. There’s always been a very tenuous link between the two.

BLVR: But the critics seem to love the megaretrospectives of established artists at MOMA and the Met. Does their revulsion toward the Biennial et al have anything to do with the very young artists that are generally shown there?

RP: No question. With criticism it’s never just between the critic and the artist, or between the critic and the curator—it’s between the living and the dead. This sort of criticism is as close to human nature as you can get. Anyone living, especially your peers, is a threat. You’re judging them, they’re judging you. That can be a good thing sometimes. Jealously, rancor, competition, those can be good things in art. But it mostly puts you in a dangerous and disadvantageous position, and one that just takes away from you so much. It’s possible to do your best work at your highest level without competing. I’m not anticompetition, but at an individual level, it can be degrading for both sides. And it doesn’t have to be that way. I’ve done pretty well at getting past that sort of thing, and it’s a relief not to have the rancor.