It is a bit odd to hear Rem Koolhaas say he is fascinated by the countryside now. His name is so intimately connected with the city, with its emptiness, its greatness, its promise and disappointments.

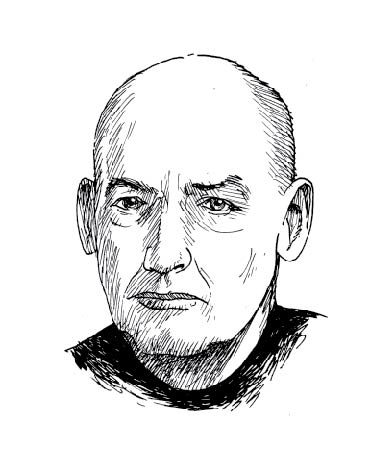

When I met Koolhaas in front of a café in the posh southern part of Amsterdam, he was dressed in a black beanie, a thin black overcoat, black trousers, black shoes. He is tall, thin, almost gaunt, with intense blue eyes and a shaved head. At seventy-five, the architect looks younger than he is.

Rem Koolhaas is the epitome of the starchitect, part of that select group of architects who get to design elaborate, extremely expensive buildings. Koolhaas is known for brash designs, for unapologetically big buildings in boxy, geometric shapes. He is no fan of flowing lines. He dislikes ornaments. His buildings rarely look anything alike. They merely share a somewhat oscillating, unstable quality. Many of them are so asymmetrical that they look as if they should capsize. It is often necessary to see them from several angles in order to grasp them.

Koolhaas is ruthless in the pursuit of his ideas. He is widely known as a difficult man. He is unyielding with clients that try to water down his designs. He is often visibly impatient with his own employees. He hates questions from journalists that he considers too obvious, too inane, too lazy. When confronted about his fierce reputation, he likes to quote Dostoevsky: “Why do we have a mind, if not to get our own way?”

Koolhaas worked as a journalist before he became an architect. He has continued to write throughout his life—he has published books on architecture that run well over two thousand pages in total (although they are full of images and sketches as well as text). The vast majority of his books deal with cities. His first is about “delirious” New York City, which he admired exactly because it was removed from the bucolic, the idyllic, the wholesome. “Manhattan,” he wrote in 1978, “has generated a shameless architecture that has been loved in direct proportion to its defiant lack of self-hatred, respected exactly to the degree that it went too far.” His attention has been consumed by the development of urban centers all over the world: the Pearl River Delta in China, Lagos in Nigeria, the ancient Roman city, and retail shopping in the West. He has spent almost his entire life in dense metropolises: in Rotterdam, Jakarta, New York, London, and now Amsterdam. His office is in Rotterdam, about an hour from the city by car. He commutes almost every day. A driver picks him up in the morning in a silver BMW. Most days he sees the countryside only en route, from his car window.

The morning of our interview, Koolhaas’s driver arrived in front of the café shortly after eight o’clock. It was raining heavily. We took our seats in the back of the car. We talked for an hour on his way to work, and another hour on the way back. The countryside that we saw from the highway was a highly artificial, heavily altered landscape: flat grassland surrounding the landing strips of Schiphol airport, huge logistics centers, and massive greenhouses that glowed brightly under a gray sky—tomatoes, peppers, and chilis growing beneath orange high-pressure sodium lights and red and blue LEDs.

In Rotterdam we passed the unassuming brick building where he was born, six months before the end of the Second World War. He still remembers the deep crater, only a few steps from his childhood home, where a German bomb had ripped open the pavement.

—Johannes Boehme

I. “IN THE FUTURE ONLY A CERTAIN PART OF OUR BUILDINGS WILL BE BUILT FOR PEOPLE.”

THE BELIEVER: In 1978, at the beginning of your career, you called New York an “addictive machine.” You embraced the anonymity of the city, its density, its freedoms. After four decades of writing about cities, living in cities, and building in cities, are you finally fed up with them?

REM KOOLHAAS: Yes, I am. There used to be something about cities that was genuinely challenging, individualistic. It’s not completely gone. But in the past they were slightly less dedicated to the demands of the market. In London and New York, market mechanisms have taken on such a dominant presence—at the cost of just about everything else—that I just do not feel the same enthusiasm for them as I did before.

BLVR: In what way has the dominance of the market changed cities for the worse?

RK: Corporate brands are now setting—almost dictating, actually—the atmosphere in inner cities. There is a kind of overload: too much communication, too much marketing. The city seems to me a system that is more and more reaching its limits.

BLVR: For an exhibition in 2020, at the Guggenheim in New York, called Countryside, The Future, you are investigating developments in rural areas. Where does your interest in life outside the city come from?

RK: I travel regularly to the holiday home that my girlfriend’s parents bought in Switzerland. And I started noticing weird things: The population of the village decreased, but nevertheless the village grew in size. Vacation rentals were built everywhere. The architecture that emerged was a peculiar kind of consumerist minimalism. I met a man whom I believed to be an authentic Swiss farmer until it turned out that he was a dissatisfied nuclear scientist from Frankfurt. There were women from Thailand, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka who were looking after the empty houses. And then I realized: It’s not just the cities that are changing. Something similar is happening in the countryside as well.

BLVR: Is the countryside merely catching up with developments in cities?

RK: No, I think that’s not capturing what is going on here. It is rather that the frivolity, the fun, the adventure of the city—its capriciousness—must be supported by an incredibly high level of organization in the countryside.

BLVR: Do you have an example of that?

RK: Farmers today are employing harvesting machines that are equipped with computer-guided precision technologies. They work fields with an incredible degree of accuracy. And they are so expensive that they have to be in motion day and night. No farmer can afford to buy one on his own. They are only ever rented out for a few days, a few hours. And this kind of efficiency is the basis for all the products that the inhabitants of the city find on their supermarket shelves.

BLVR: Efficiency can be more ruthlessly enforced in the countryside?

RK: In a way, yes. In Nevada, on the border of California, just outside of Reno, there’s a vast area where American corporations are building gigantic server farms: Amazon, Google, Apple, Walmart. The business park is larger than the city to which it is attached. These buildings are so huge, so entirely utilitarian. It’s new that something so big can be so faceless.

BLVR: What was your impression when you visited these buildings in the desert?

RK: Awe. Simply because of the scale of these structures. We went into one of the server factories and inside were these incredibly abstract rooms lit with bright red lights. Contemporary architecture has not produced spaces of such intensity for a long time. None of this was made for human beings. Everything in there was constructed for machines.

BLVR: Are there spaces for the workers?

RK: For the employees there are only small rooms to relax in. They are paneled with Norwegian wood and Buddha statues—a debased kind of humanism, if you will: A little bit of mysticism, a little bit of warmth. But not too much of anything.

BLVR: Do you find that an attractive proposition: to design a building exclusively for machines?

RK: Yes, very much. In the future only a certain part of our buildings will be built for people. A vast new architecture will be conceived for machines. And it will largely be created in the countryside. That’s very, very interesting.

BLVR: As an architect, what do you think are the advantages of designing for machines?

RK: You can get rid of beige. You can suddenly make rooms look incredibly hot or cold. The need for human comfort can be very limiting when it comes to the design of buildings.

BLVR: What do you find troubling about beige?

RK: I don’t find it troubling per se. In certain situations I have actually learned to like it. But I find it difficult to feel any enthusiasm for it. I simply feel a slight disappointment that the final aesthetic consensus of humanity is gravitating toward beige.

BLVR: You had higher expectations?

RK: I finished studying architecture in 1972. During that year the World Trade Center was being built in New York, the Concorde was tested in the skies, and American astronauts flew to the moon. You can imagine how the rest of the century felt in comparison.

BLVR: What is that you enjoy about designing large buildings?

RK: What fascinates me about large designs is that the traditional work of the architect becomes impossible in some ways. In the planning of huge buildings, I can no longer simply assert my own character, my personality, my taste. With a certain size, the work becomes much more collaborative; it’s more about engineering, not a purely artistic endeavor. You need a completely different mentality. I appreciate being part of a greater effort, together with other people.

II. FRAGMENTS OF UTOPIAS

BLVR: Today, less than half of humanity lives in the countryside—

RK: —which is one of the most abused statistics of our time. It has been quoted, again and again, as an excuse to concentrate almost exclusively on cities. The supposed inevitability of this development must be questioned. Cities today are places where it has become very difficult to inject new, big things. Everything that demands size and space takes place in the countryside today, which also means that a lot of us barely notice any of it. It happens outside our radar.

BLVR: Aren’t there really two speeds at play in rural areas: one of rapid technological progress in some areas of agriculture, and in other parts things are actually getting worse, with very high unemployment rates and the majority of young people migrating to the cities?

RK: A much less pithy insight would be: there is a new balance in the countryside between incredible artificiality and very lyrical, poetic zones—and it would be a mistake to call them “nature,” because it will be a decision to leave them in their so-called “naturalness.” The new reality in the country will take place between absolute clinically precise science and very emotional, romantic moods. Between nature reserves on the one hand and on the other a new agriculture that grows fruits and vegetables in lab-like conditions: in huge facilities where it will no longer be necessary to kill vermin because in these totally controlled environments there will be no vermin.

BLVR: You traveled extensively in preparation for your exhibition about the countryside. You were, among other places, in Kenya, in Nigeria, in Russia, in China. Which place impressed you the most?

RK: I always find it very difficult to answer questions about superlatives. [He pauses for a moment.] Have you ever been to Vladivostok?

BLVR: No.

RK: It’s a totally amazing place. The remnants of this lost Soviet world are everywhere. It is freezing cold. Imagine a Siberian landscape with high hills. And in the hills are these two-

hundred-meter-long Soviet-style blocks, far apart from each other. There is a market in the city center where whole cow heads are lying around, like in Africa, but they are completely frozen. The city is quite poor, which is why many secondhand cars are imported from Japan. There are all these fragments of different utopias colliding—that was really striking.

BLVR: The narrator of To Kill a Mockingbird describes rural life in Alabama as follows: “People moved slowly then. They ambled across the square, shuffled in and out of the stores around it, took their time about everything. A day was twenty-four hours long but seemed longer. There was no hurry, for there was nowhere to go, nothing to buy and no money to buy it with.” Have you encountered this kind of disconnected slowness anywhere?

RK: No. It is also a very romantic, aestheticized view of rural life. It’s really interesting how many stories begin with the idea that there was nothing there. I’ve just been to Doha, and every story about the city begins with a variation on that sentence: “There was nothing there.” But, of course, this is almost never true.

BLVR: For many city dwellers, the countryside is above all a place of longing. They believe that their hectic lives could come to rest there.

RK: This is obviously a widespread idea, yes. But what people in cities do not see is that the countryside is also under a great deal of pressure. The relief that they are hoping for is now being sold to them as wellness, in the context of resort hotels where there is almost a compulsion to relax. It has become just another form of pressure. And architecturally it is not interesting at all. In the ’60s and ’ 70s, there were still architects who were seriously thinking about what a modern way of life in the countryside might look like. That is, as far as I can see, largely over.

BLVR: Why is that?

RK: Because there is no longer any demand for such experiments.

BLVR: The countryside has been developing a political life of its own, at least in Europe and North America. The populist political insurgencies in recent years all had their core constituencies in the countryside: the Brexit campaign in the UK, Marine Le Pen’s Front National in France, the Alternative für Deutschland in Germany, and of course Donald Trump’s presidential campaign.

RK: Yes, but why does that happen? The reason is precisely the disrespect, the neglect of rural areas. There are forces at work here for which there is no political discourse. I think the implication that we all need to draw from this is that we need to pay attention to the countryside in a completely different way.

BLVR: But that seems to be far from easy, even for yourself: your firm, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, is still almost exclusively designing buildings in major cities, not in the countryside.

RK: Yes, that’s true. I’ve been trying very hard to get work outside of big cities for some time, but it’s very difficult. The current perception of what an architect does certainly compounds the problem: architecture is so much about exaggeration, extravagance, ego, identity, and none of these factors play any role in the countryside. People in the countryside often tell me: “We don’t need that.” And I understand them completely.

BLVR: You have encountered a lot of suspicion?

RK: I experience that again and again. Constantly, actually.

BLVR: The starchitect as a threat.

RK: Rather, as the embodiment of redundant abilities. Who needs extravagance?

BLVR: You once called yourself an optimist. Are you an optimist when it comes to the future of the countryside?

RK: I feel no optimism for anything in particular. I just think that, as an architect, pessimism is not a particularly interesting position.

BLVR: Have you ever lived in the countryside?

RK: For a very short time, when my parents moved to Indonesia with us in the 1950s. My parents were a bit hippie-irresponsible, and they just left me and my brother with an Indonesian family in the heart of Bali for two weeks while they traveled around the island. I was nine years old then. We helped with the work on the rice paddies and made small dolls for tourists.

BLVR: Was this world foreign to you, a child who grew up in the city?

RK: No, it didn’t seem that way to me. As a child, I did not feel the contrast between the city and the countryside very acutely.

BLVR: You spent much of your childhood in Indonesia. Do you still feel at home there?

RK: I still feel a great affinity for this region of the world. When I arrived in Indonesia with my parents, the country had just gained independence, and it was very exciting to experience the euphoria that can be triggered by an event like that.

BLVR: You came from Rotterdam, which was still largely in ruins, to Jakarta.

RK: Yes, and Indonesia seemed much better to me. There was more fun, more food, more tastes, more freedom. We took a ship to Indonesia, which took three weeks. On board there were Indonesian sailors and they taught me and my brother the language. When we arrived I already spoke much better Indonesian than my parents. I felt very quickly at home and had a lot of freedom there.

BLVR: You were born in 1944, during the Hongerwinter in Rotterdam, when the Netherlands experienced the last great famine in Western Europe, precisely at the moment when people in the cities suddenly realized how dependent they were on rural food production.

RK: I was born not far from here, in a plain brick building with a balcony, only a few meters away from a big bomb crater. But I have no memory of the famine itself. And for my parents it later became the backdrop for the stories that they liked to tell. My father was a journalist. And at the time he somehow managed to obtain three hundred white laboratory rats from somewhere. My parents like to tell the story of how they found the rats that had been delivered to their apartment, at night, in the dark. And how they ate the rats afterward. They very much took things in stride. It was not remembered as a traumatic, negative thing. What I remember instead, after the war, was a universal sense of exhilaration.

BLVR: The Irish poet William Butler Yeats once wrote: “In the great cities we see so little of the world, we drift into our minority. In the little towns and villages there are no minorities; people are not numerous enough. You must see the world there, perforce.” Is the countryside a place for realists?

RK: I find the idea intriguing, even though I think ultimately I disagree with the ideology behind it. I do not believe in a fundamental contrast between city and countryside. Whether the countryside is a place for realists, I do not know. The number of realists in rural areas is probably not higher or lower than in cities. I have not met many realists in my life anyway.

BLVR: What is a realist for you?

RK: This may be a somewhat idiosyncratic definition: for me, a realist is someone with a joyful grasp of reality.