Martin Luther King Jr. called him “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.” To Congressman John Lewis, he is an architect of the nonviolence movement. Author David Halberstam believed he was responsible for sowing the seeds of change in the South as much as any person (except maybe King). Rev. James M. Lawson Jr. was born in Pennsylvania in 1928 and to this day continues his life’s work in the service of direct action for social justice.

In 1955, Lawson was teaching in India while studying Gandhi’s life and work. It was there that he read newspaper accounts of the Montgomery bus boycott and first learned about Martin Luther King. Back in the U.S., after the two men met, Lawson went to Nashville, where he led workshops to prepare for direct action—marches, boycotts, sit-ins, and picketing. He also enrolled in Vanderbilt Divinity School, which had just begun to accept a small number of black students. He soon raised hackles by acting like a normal human being: eating in the cafeteria with white classmates and joining in intramural sports. When trustees realized that their black divinity student was the key figure behind the protests, two members of the board demanded and won his expulsion. Though the white faculty rallied in his support and Lawson’s enrollment was reinstated, he chose to complete his degree in Boston. (His relationship with Vanderbilt was renewed—or perhaps redeemed—in 2006, when the onetime subversive was named Distinguished Visiting Professor.)

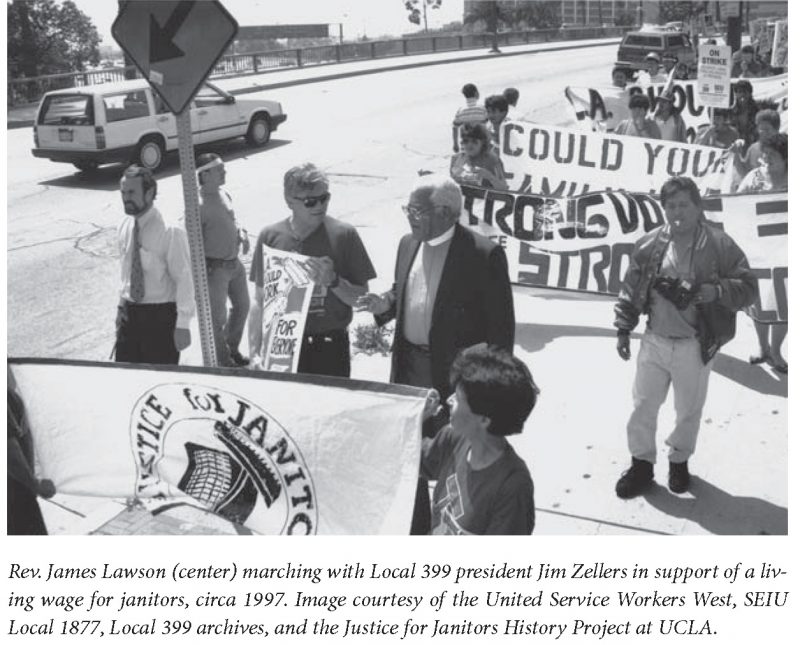

Lawson coordinated the Freedom Riders, interracial groups of activists who rode interstate buses into the Deep South to exercise their civil rights under the Supreme Court’s anti-segregation rulings. They endured jailing and violence from mobs that included local police and the Ku Klux Klan. Years later, Lawson relocated to Los Angeles (where he has been arrested more times than during all his time in the South). As pastor of Holman United Methodist Church, he made nonviolence training part of Christian education and soon began to offer workshops, free, to the public.

Today, past the age of eighty, he continues to assert that justice is a tenet of all religions and that religious leaders must stop blessing violence and war. Lawson has moral authority and significant influence with elected officials, but still believes he can accomplish more in the streets than in the halls of power.

—Diane Lefer

I. WITHOUT PULLING A GUN

THE BELIEVER: You’ve said we have sufficient activism in this country to have a better country than we have. What are we getting wrong?

JAMES LAWSON: Activism is not appropriating and practicing the Gandhian science of social change. What Gandhi called nonviolence, or satyagraha—“soul force”—is both a way of life and a scientific, methodological approach to human disorder. It is as old as the human race and can be found in the oral and written history of the human family from way back. Then Gandhi began to put together the steps you need to take to create change. He is the father of nonviolent social change in the same way that Albert Einstein is the father of twentieth-century physics—not the inventor but the person who pulled it together.

Gene Sharp wrote the classic book in the field, The Politics of Nonviolent Action. Looking at different centuries and different cultures, he discovered 198 different techniques—various forms of protest and agitation and strikes, sit-ins, and civil disobedience, and there are many more, because people have invented other techniques. Activists ought to study this so they can become like military strategists, not just operating out of the adrenaline that develops out of anger.

Today, much of our activism does not discuss, study, and apply what nonviolence theory offers the struggle. Too much activism gears itself to lobbying legislatures and Congress and the president. That activism does not have the clout that the Council on Foreign Relations has, or that Exxon has or the Pentagon has, so it’s lost. Again and again, when a movement begins to raise its head in the United States, the so-called political social progressive forces immediately try to surround it and guide it into the channels they think are important. I experienced this as early as 1961 with what I think to be very wonderful people in the Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson administrations. Robert Kennedy was mobilizing foundations and others to put money into voter registration. In meetings, he pushed very, very hard and eloquently that we should end the Freedom Rides and go toward voter registration. In 2006, when the coalition of immigration groups came together to start the big marches, they were immediately approached by foundations and political groups that said the way to do this was to lobby for a good bill.

BLVR: But voting rights and voter registration paved the way for the election of Barack Obama. Doesn’t that show we can bring about change through the ballot?

JL: Pulling down the WHITE and COLORED signs across the country—the NO JEWS, NO MEXICANS, NO IRISH, NO WOP, NO INDIAN signs—has done far more to prepare the mind of the nation for a black president than voter registration. Desegregation of the sports world and the university and the professional world has done more to prepare the American mind than the Voting Rights Act of ’65. The country has grown since the ’50s and ’60s precisely because we put into play those forces that began the desegregation process while real access to the right to vote still hasn’t been settled in the United States.

Obama is one man, and we are still trying to establish a democracy. In the meantime, there’s the chaos and the greed. JPMorgan publicly said that this time of recession is a great time for it to buy up assets. The bailout was used to give dividends to its investors. There’s no indication that these engines for self-destructing our country have stopped or slowed down. And while the visible signs of segregation have come down, the systemic stuff is still there. Blacks are still largely the last to be hired and the first to be fired.

The peace movement has failed to slow down militarization and the empire elements in our country, and it has failed to stop war, because it does not understand that the road to peace is justice. The peace movement does not have the focus that dismantling racism and poverty in the United States is the critical issue for the security of the nation. Stabilizing families by good work, by health care, is the critical issue for the security of the land and the well-being of the land. Only by engaging in domestic issues and molding a domestic coalition for justice can we confront the militarization of our land. We must confront that here—not over there. Iraq and the Middle East are not the central, pivotal places for the well-being of the American people. The central pivotal place for three hundred million people here is the United States and our domestic policies.

BLVR: You were willing to go to prison to protest the Korean War.

RJL: That’s not how it happened. I was already determined to resist segregation and I felt conscription was as immoral as any Jim Crow law. You know the early settlers in US came here fleeing British and Dutch conscription. Still, I registered for the draft at age 18 but I scribbled in the margins of the pages that I didn’t know if I was doing the right thing. Then I joined FOR [Fellowship of Reconciliation, the international pacifist organization,]. My decision firmed up in 1949 and I sent my cards back. But you see it was peacetime and I wasn’t protesting a war, but the draft itself. Then the Korean War caught up with me and I did go to prison.

BLVR: But there’s such a sense of urgency about the war. People are getting killed—we are killing people–right now over there in Afghanistan and Iraq.

RJL: The urgency is to stop the violence in our midst. Five women are killed a day in the United States by intimate partners or former partners. Five a day! Domestic assault is the major cause of pregnant women going into the hospital. Two to four million women enter the hospitals primarily out of a result of domestic assault. Sixty-one thousand people die every year as a consequence of their work. Some of those deaths include homicides in the workplace. Sixty-one thousand a year. This figure was in the Los Angeles Times, from 2000. The urgency needs to be connected here.

Nobody even knows in this country how many unarmed people who are not committing a crime are killed every week. The Stolen Lives project back in the 90’s documented four a week by police forces. Some of the lawyers from the National Lawyers Guild with whom I was working here in Los Angeles at the time told me that was the tip of the iceberg because there’s another number of people being killed every day and every week in prison and jails, and those figures aren’t even known. Rarely is a police officer held responsible. Those deaths in the 90’s ranged from age 13 to 79 and while they were mostly black, there were also Anglos and Asians and Latinos in that group. Two or three years ago the LAPD SWAT team killed a father and a 19-month-old. I could have gotten that father to surrender if they’d been willing to back off and give me the time to do it. There’s probably dozens of people on the police force – women – who could have done it. Instead we send in the SWAT team. The Christopher Commission report after the ’92 urban riots commended the women on the force for quelling violent situations without pulling a weapon. That got almost no attention. I asked the chief, Willie Williams, if they were going to highlight how women in the LAPD went into situations and calmed things down, made arrests, stopped abuse in the family, very often without raising their voices and without pulling a gun. He acted as though I was trying to provoke him. Another study showed many women officers had masters degrees in education or social work but could not find jobs that paid as well as the LAPD. So the women came in not only with a higher educational level than the men but a whole different approach to law enforcement.

BLVR: Not to defend police killings, but isn’t that a relatively small number compared to the way we civilians kill each other?

RJL: My point is that the violence we’re facing is not the violence over there. As an aside, Newsweek for this week came in and they have an interesting piece on the history of terrorism in the US in the 20th century. There’s not a word there of more than 6,000 black people who were lynched. Nothing about major riots in Rosewood, Florida and Tulsa, Oklahoma and I don’t know how many other places where white mobs destroyed black communities. That’s terrorism and that’s the problem about talking about violence in the US–there’s a very limited picture, a limited perspective. What about the death penalty in this country and the numbers of innocent people who’ve been executed? Isn’t that terror? A number of scholars say the United States has the most violent history against labor unions in the world. At the turn of the century you had 100 people lynched and 100 shot down during strikes and labor disputes in a single year.

Personally I have no doubt that violence in the street is coming from violence in society—violence in speech, in thought, in behavior. The violence in films is just astounding. Then you’ve got a problem with some hip-hop and gangsta music and there’s nothing happening in American society to deal with correctives. It’s left entirely up to the household and the parents though all of us live in a social environment that is just as influential on our personal development. We maintain that we are a culture that has a high regard for the sanctity of life but we have never had that and this is compounded by the fact that we have never examined our own violence. So I maintain that the Iraq war and Afghanistan war and 800 military bases around the world are an emanation of the violent spirituality in the US. We have a problem as a culture. We believe that violence is effective, that violence works.

II. COMPARED WITH WHAT?

RJL: We call the Revolutionary War of 1776 a good war and we continue to teach that this good war produced benefits. When we study that war we do not study the agitation and protest which took place fifty years before. The Liberty and Justice cry, the town hall meetings, the fact that as the colonies developed government, citizens — mostly white men — went directly to the legislature to talk about the issues and to challenge them. We don’t talk about the civil disobedience before that war. No taxation without representation. The petitions and protests to King George. The refusal to buy British cloth. The whole range of nonviolent protest and agitation.

BLVR: I did learn about that in school, but we were always taught that we had to have a war because nonviolent protest didn’t work.

RJL: Yes, I agree, that’s the way it’s taught, when it is taught. But those protests represent the empowerment of the people and the sense that people could play a role in making the decisions, that they did not have to consent to their own shackles by government, that they had the right to say no. That is essential nonviolent theory. Even an authoritarian government has to have the consent of the people. When the people withdraw that consent the government can’t survive. It’s inevitable that the government will falter. You were taught by people who had never experienced the 20th-century explosion of nonviolent struggle and had never read or studied Gandhi. The Gandhian methodology claims that always before you get involved in a nonviolent campaign there’s a whole period of persuasion and consciousness raising. It’s clear that was happening in the colonies there and then.

BLVR: So the colonists gave up on nonviolence too soon?

RJL: It was the 18th century. For whatever reason, the human race wasn’t ready to see this. Look what happens in the 20th century, the explosion of knowledge in biology, physics, psychology, surgery. New knowledge of the brain and the heart.

BLVR: OK, I think I get what you’re saying–that we don’t dismiss the advances in science just because people in 1776 didn’t make use of them.

RJL: The word “nonviolence” wasn’t even really used until Gandhi took a term from Jainism—ahimsa—that means do not injure living things. He translated it as “nonviolence” and used that term with the Muslims and Hindus in the challenge to racist policies in South Africa.

When you study the history of our country, most of the people in the settlements came from a Europe shackled by monarchy, tyranny, conscription and wars. They weren’t ready. The only people in that era who thought there was a better way were the Quakers. Their 17th-century movement said in every human being there is a spark of God. And they were imprisoned, they had their hands hacked off for this peculiar understanding they had of God and the New Testament and Jesus. And here is successful nonviolence. From around 1681 until 1740, there were no Indian wars with the Quakers in eastern Pennsylvania under William Penn. He wrote to the Indians before receiving the charter from King George. He wrote “We are coming and we want to come as brothers, not to hate you or mistreat you in any way.” Indian wars were raging all around them, but as long as Quakers were the dominant force in that colony, not a single settler was killed by an Indian and no war took place. There was no slavery in that colony. Later in Pennsylvania you have the influence of Benjamin Franklin who wanted to wipe the Indians out.

There has never been a serious look at the successes of nonviolence and the failures of violence. We live in a society where the Reagan Revolution, so-called, takes credit for ending the Cold War whereas I use a textbook, A Force More Powerful by Ackerman and Duvall, that describes the nonviolent campaigns in the ’80s and ’90s in Europe and around the world. For example, the Solidarity movement in Poland. In the American newspapers, it was always described as being anti-Soviet Union. But when the movement began in the ’70s they were mad at the Communist government and wanted independent unions but they never dared to think they would be able to topple one-party rule. Their movement was crushed. Then they reorganized around nonviolence. Solidarity followed Gandhi and King, both of whom had been translated into Polish. That was at the heart of the Solidarity struggle and that isn’t mentioned or talked about and that’s what toppled the Communist tyranny in Poland. The movement was able to recover and about the middle of the 1980s Lech Walesa and others added the demand for free parliamentary elections to the negotiations.

By the way, Solidarity is the only overseas union-organizing effort that the US has ever supported. Union organizing under the apartheid regime in South Africa was called Communist. We killed off union leaders in Central America and we’re doing it now in Colombia. We encourage the killing even when we don’t teach it.

I maintain that there are four other major factors which have taught us to depend upon animosity and violence. One is what can be called the American Holocaust, the decimation of the Native peoples, the indigenous people, 13-15 million people who we cut down in size in less than 200 years to less than 250,000 people. That has made us sense the efficacy of violence: We stole, we took the land. Then the establishment of slavery taught violence. It continues to teach violence.

I maintain that racism and slavery are major contributions to the violent perspective. And sexism is akin to racism. Women were excluded from the Constitution which denied them the vote. Women were not created equal, not included in “All men.” The whole anti-abortion business is but a subterfuge to maintain power over women–to say that women are not equal moral agents in the sight of the Creator as are we men. Various aspects of Christianity teach what they call the “headship” of the male. In 1996 the Southern Baptist Convention adopted that as one of their belief principles and there are other denominations that have the same principle. The Vatican insists that a woman cannot be called by God to be a priest. Their position is that Jesus was a male and Moses was a male so a woman was never called and can’t be called. If there’s any task in the world that a woman can’t do, that supports the inequality and submission of the woman and all of that is a violent perspective. It has continued to encourage family abuse.

Finally, I think a major influence is “plantation capitalism” with its emphasis on greed. That’s not the Adam Smith form of capitalism.

LVR: What do you mean by “plantation”?

RJL: I do not think that you can have 250 years of a peculiar national institution like slavery without it affecting economic thought or the attitude toward labor. At the heart of plantation economics was the notion that there are people who do not deserve reaping the benefits of their labor. Workers were property, not human. Slaves were paid nothing but subsistence and died early. Today you have all kinds of demands on the part of capital that workers are not to receive wages enough to live on.

There’s an annual publication, the State of the World, that indicates over and over that the United States barometers of wellbeing have lingered behind the advances of Europe and Canada and Japan. Very little of that is ever reported in the American media so the notion is we are still the greatest country in the world. Compared with what? Infant mortality? We’re atrocious. Literacy? Health care? Housing? According to the Wall Street Journal, the barometer of wellbeing is not infant mortality but how many millionaires are created. Then they changed it to billionaires. Our social fabric is atrocious. It’s because we’re in the grip of plantation capitalism.

III. NON-RESISTANCE VS. NON-VIOLENCE

BLVR: The civil rights Movement of the ‘50’s and ‘60’s has been well documented and David Halberstam wrote a wonderful account of your role in his book The Children, so I’d much rather hear about how you’ve applied nonviolent methodology since then.

JL: I began working in Los Angeles with Local 11 – the Restaurant and Hotel Workers Union – with nonviolence workshops twenty-five years ago. First I wanted to help people develop the character and the courage to organize. The workers were heavily intimidated and harassed on the work scene so that they were not willing to talk about their work pain, their wages. We found a major barrier in their fears, frustrations, and complicated acquiescence. Some of that produced anger in them, some of it also produced abuse in the family. But what we decided to do was to work on one-on-one activities—and I called it evangelism. One-on-one. We taught going to the worker in his community, in his home, and not doing this once, but doing it systematically, maybe once a week, for as long as it took. The organizer was to be generous and kindly throughout, use no harsh language and approach the person with compassion and love. Do not concentrate on getting the person to join a union. Concentrate on helping the worker talk about his situation on the job, in the family, in the community. Get to the point where the worker is talking about his fear, his frustrations, his pain. What I had found in my ministry–and I did not really fully understand it at the time and I don’t fully understand it now– but what that did was ignite a spark in the worker. Then, with the organizer, it meant beginning to connect with other workers and beginning to realize that organizing with them is the key to changing his scenery. That represents nonviolence: helping this harassed person re-find his basic humanity and talk about it. This approach came directly from my understanding of nonviolence and my experiences in the 50’s and 60’s.

Then I began to have conversations with other clergy, getting them involved in recognizing that poverty–economic injustice–especially with people who are working, is a major wrong that has to be corrected. In 1996, I invited a number of my colleagues to come to talk about this. We organized CLUE [Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice]. We would get a local congregation to organize an Economic Justice committee where they began by investigating their own congregation and their own people. That is, find out how many poor folk we have who are working people. Find out how many union members we have. Find out what their situations are. It also meant looking at church staff. Are we participating in poverty wages? We have to clean up our own act.

BLVR: How did you come to your own commitment to nonviolence? Because you once told us about using your fists on someone—

RJL: Oh yes.

BLVR: — and you had a twinkle in your eye when you said it.

RJL: When I was four, my Dad was appointed to the St. James AME Zion Church in Massillon, Ohio. And I probably romanticize it, but for me it became another kind of womb that nurtured and framed and formed me. At the same time, however, it is the first time that I became aware of people who called me racial slurs on the street where we lived and in the parks. Even by that time I had a sense of my own being and my response was to slap the person or to fight the person. My mother was very much opposed to violence in all its different forms and said so. My Dad was not and in fact when he pastored in Alabama and South Carolina, he carried a gun and he showed us that gun. I remember that very well.

When I was in 4th or 5th grade, I came home from school, and my mother had an errand for me to run. It took me up Second Avenue to Main Street where I made a left turn and just after I turned left onto the Lincoln Way block, the main business section, there was a car parked at the curb. The windows were all open–it was a warm, beautiful day, and as I approached on the sidewalk, a child stood up in the front seat and yelled the “N” word at me and I went over to the car and slapped the child. I ran on and finished the errand and ran on back home.

Then, in the kitchen with my mother, I told her about this incident and she said to me–I remember the two major things she said. The first one was “Jimmy, what good did that do?” And I remember her finishing with, “Jimmy, there must be a better way.”

That moment was a numinous experience, an experience in which the whole world stood still. And to this day I do not know what was happening in that household. We were a fairly noisy household. There were at least eleven of us at that time in that house and we had a piano and radios so there was always movement. How that place was so still that day, I can never, I can never, I can never know. But in any case, it was. The world stood still and in the midst of that experience, I heard a voice which I later began to recognize was my own voice and yet it was not my voice because it didn’t come from me. It came from way beyond me and it was also in the depth of me. That voice said, “Jimmy, never again will you get angry on the playground and smack and fight. You will never again—” And then I heard it say, “And you will find a better way.” So I did from that moment on never again strike out at youngsters who used the “N” word on me. I never again got angry and engaged in a fight on the playground. I tried to find a better way.

BLVR: Did you find it?

RJL: Some time later on the street almost the exact same sequence occurred. I was running an errand on Lincoln Way, a child in a parked car yelled a name at me. But this time I went over and I didn’t hit the child. I talked to the child. I asked his name and I gave him my name in a way that was not confronting him but engaging with him. We had a good conversation and after I’d had enough time to let the child see me and touch me and know me, I ended by telling him he should not call people names. We parted in a very friendly fashion. I wanted to wait for the parents and talk to them too, but I did have that errand to run and in the end I couldn’t keep waiting.

BLVR: Is it a struggle to give up the anger? Is it a decision you made at that moment in the kitchen, or is it something you work on constantly?

RJL: Well, you know you still have to work on it, at 80. But no, it was, as I say, it was a numinous moment and it changed my life forever. That doesn’t mean that I didn’t get angry in the 60’s. It’s just that you do what the great religions all teach: Be angry but do not sin. Be angry but don’t be foolish. Be angry, but direct it in a way that is commensurate with who you are as a human being.

Between those years, 4th or 5th grade, and college, 1947, I was a reader and I was fascinated by Jesus so I read the four books in the Bible about Jesus frequently and had become very much aware of what’s called “The Sermon on the Mount.” Matthew 5, 6, and 7. That’s where “turn the other cheek” is specifically mentioned and as I worked for the better way, that’s what I practiced all through junior high and high school. By the end of my high school years, I came to recognize that that whole business — walk the second mile, turn the other cheek, pray for the enemy, see the enemy as a fellow human being– was a resistance movement. It was not an acquiescent affair or a passive affair. I saw it as a place where my own life grew in strength inwardly and where I had actually seen people changed because I responded with the other cheek. I went the second mile with them.

Then in ’49 or ’50 I read the black theologian Howard Thurman who said that the Gospel of Jesus is the survival kit for people whose backs are up against the wall. His book, Jesus and the Disinherited, was very powerful for me because it was my experience reaffirmed. Thurman says that the oppressed will be angry, they will have great fears of all kinds, they will practice deceit, and he calls these “the hounds of hell” for these people. He talks about the way in which the anger can consume you and destroy you, so the management of that anger is important and he says the Gospel of Jesus is a vehicle for handling and dissolving that anger and directing it.

We think of the Eastern religions as teaching us to detach and handle our emotions well. In my experience, Jesus of Nazareth has been a major force for my detaching myself from my fears and not being overcome by fear. Gandhi said that he read “The Sermon on the Mount” every day as a part of his reflections and meditations.

BLVR: I’m listening to you talk about Jesus at a time when we see so much fundamentalist hard-line religion. You are a deeply religious Christian and I’m trying to figure out how you do it. How you work very comfortably with people of all faiths, and people like me of no religious faith. Is that a spiritual understanding, or is it pragmatic, for political purposes?

RJL: You cannot be human and alive if you do not have faith. It’s faith that makes you wake up in the morning, makes you get up, causes you to have goals and purposes for the day, causes you to love, and I would also say maybe even hate—though that’s wrong, but –

BLVR: When you said that once, about getting up in the morning and about farmers having faith when they plant the seeds, I thought, well, that’s not faith, that’s hope. Then I realized I do expect the sun to come up in the morning.

RJL: Yes.

BLVR: I don’t just hope it will

RJL: That’s right. It’s not just hope. You have confidence in the universe. You have confidence in Life. We all do. So that makes me critical of religion because I think that they often put so many layers around faith that people then think that to have faith they’ve got to believe in the Virgin Birth or believe the earth is flat or something. Whereas that’s not really faith. Faith is the dynamic of you getting yourself connected up to the gift of life and you don’t have to do that by believing in God. I think the artist does this in ways that can teach us. I think many of the great scientists have done this in ways that teach us faith.

Focus on the Family and people from their religious perspective see what they call traditional marriage as more powerful and significant than the right of gay and lesbian people to have full human dignity and rights. But at the heart of both the Jewish and the Christian Bible is the notion that you cannot get to God if you are alienated from your neighbor, if you have pushed the neighbor into nonbeing or you hate the neighbor or deny that another being shares your own humanity. You shall love the alien, you shall love the stranger, treat the stranger as you treat your fellow citizen. That’s clearly in the Torah and then Jesus comes along and summarizes it in the first law: Love God with all your heart and mind and strength and your neighbor as yourself. How can you claim to love God who is invisible if you hate the neighbor who you can see?

BLVR: Has class become the dividing line now rather than race? You’ve also said the only movements that have ever worked—whether the Christian movement of the 1st century or the civil rights movement of the 20th century, were those in which people from every class participated.

RJL: Yes. Any good movement is intercultural and interclass. People of different genders are involved, and young and old. Educated and uneducated people are all involved. And that’s the only kind of democratic nation possible–a nation in which all sorts of people participate in helping to shape the government in the right direction.

BLVR: You use military language a lot and I imagine some people criticize your use of the language of war.

RJL: Bernard Lafayette called our Nashville workshops a course in nonviolence that was equivalent to having gone to West Point for military purposes. There are similarities between armies and the military and nonviolence. We call for our troops to be willing to suffer and die or be injured and hurt in Afghanistan and Iraq so there has to be a doctrine of suffering. Over the years I’ve heard people say, “Well, if I do it nonviolently, I’m going to get hurt.” In nonviolence we have to teach you can be injured, you can be killed in this action, in this work.

BLVR: And I guess when you use the language of war, it also emphasizes that nonviolence is a powerful force. It’s not passive.

RJL: The military are the most highly organized people for violence and when I use some military language I am indicating the extent to which nonviolence must also be a highly organized and disciplined affair. It is not passivity that acquiesces. It is action that engages in serious study, investigation, analyzing, understanding the scene and the problem you’re trying to deal with and then organizing to do it. Activism has to have strategic plans. It has to have longterm and short term goals. It must try to institutionalize the process.

Gandhi did not like “passive resistance,” “non-resistance” which were Christian terms. He did not like “pacifism.” He was not satisfied with any of the historic terms used out of either Western Christianity or out of Western pacifism and I didn’t like those terms either. I adopted Gandhi’s term of “non-violence,” see, and that made more sense to me. Part of my critique of pacifism was that, in my college years, many of the people at the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the American Friends Service Committee said that love is non-coercive, that love could not pretend to power. And that did not strike home with me. It was clear to me that I had been empowered and that I had met power.

I’ll never forget the very first question that King asked me in the first workshop on nonviolence that I helped to lead for SCLC in Columbia, South Carolina. The very first question that King asked was about power. I knew that Martin was being besieged by all the pacifists in the country who were saying, You’re too aggressive. You’re too militant. So I answered him that nonviolence uses power. The Greeks defined power as the capacity to accomplish purpose. Power is a Creation-given thing. A baby could not develop into an adult human being unless there were power in life itself. And so I insisted that nonviolence does seek to push, engender, and change power in every way possible.

BLVR: Is there a point where nonviolence won’t work anymore? Does society reach a point where things have gone too far?

RJL: Before we decide that nonviolence won’t work, we should do a deep historical analysis of where the violence has not worked. Violence has not worked in the Middle East. It’s only escalated for 80 or 100 years. Until we de-escalate the military budget in the US and turn that budget into plowshares, building a world-class educational system that embraces every boy and girl anywhere in the country, until these things begin to happen on a serious note, we can’t know if there’s a place where nonviolence will not work.

Over the millions of years of our journey, the wisdom of the human race developed ethical standards for us human beings on a personal individual basis but these are the standards that States repudiate. The States claim if I kill in the name of my government, it’s OK. If I electrocute a murderer, it’s OK. But I say, as an ethicist, that the ethical standards developed by the human family also apply to the States.

We can only have the world that will really provide for babies’ health and security if we the people not only demand of ourselves high standards but demand that our corporate entities and government do the same. We must stop pretending that this is not possible.