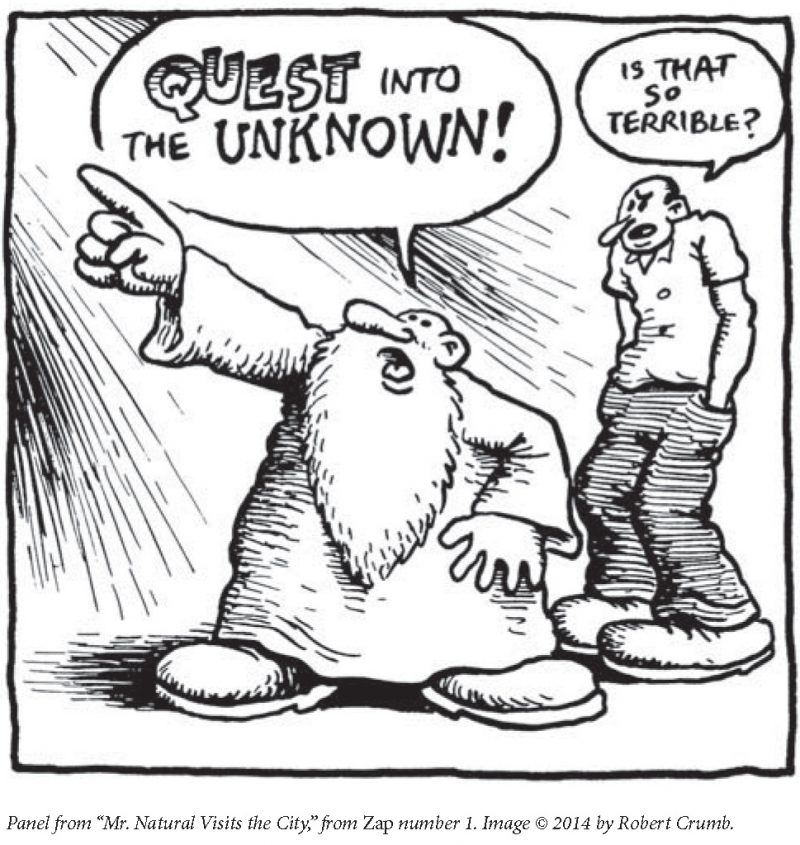

He might deny it, but when Robert Crumb published Zap Comix number 1, in 1968, he invented a new form of art as surely as Marcel Duchamp did in 1913 when he made the first “ready-made” sculpture. Duchamp used a familiar object—a bicycle wheel—and imbued it with new meaning by changing its context, placing the wheel in his studio as a work of art. Crumb, meanwhile, took the familiar mid-century comic book and messed with it, stripping it of its patriotic superheroes and huggable, funny animals and filling the pages instead with psychedelic and psychologically charged imagery.

Underground comic books existed before 1968, but none had the potency or popularity of Zap Comix. Its success was founded on Crumb’s accomplished draftsmanship and surreal wit, as well as his shrewd commercial instincts. His psych-pop sensibility was appealing to the late-’60s crowd, specifically to those frequenting the head shops and hippie boutiques that were sprouting up and looking for something to sell next to the bongs and beads. When these stores bit, Crumb inadvertently opened up a distribution door for hundreds of artists.

Crumb was the first to conceive of the comic book not as a genre but as a medium for anything. He found an audience hungry for picture stories that related to their own experiences. Underground comics fed the need, and the impact of his moves changed the medium forever. Without Crumb there might be no Art Spiegelman and no Maus, no Lynda Barry and The Good Times Are Killing Me, no Gilbert Hernandez and Love and Rockets.

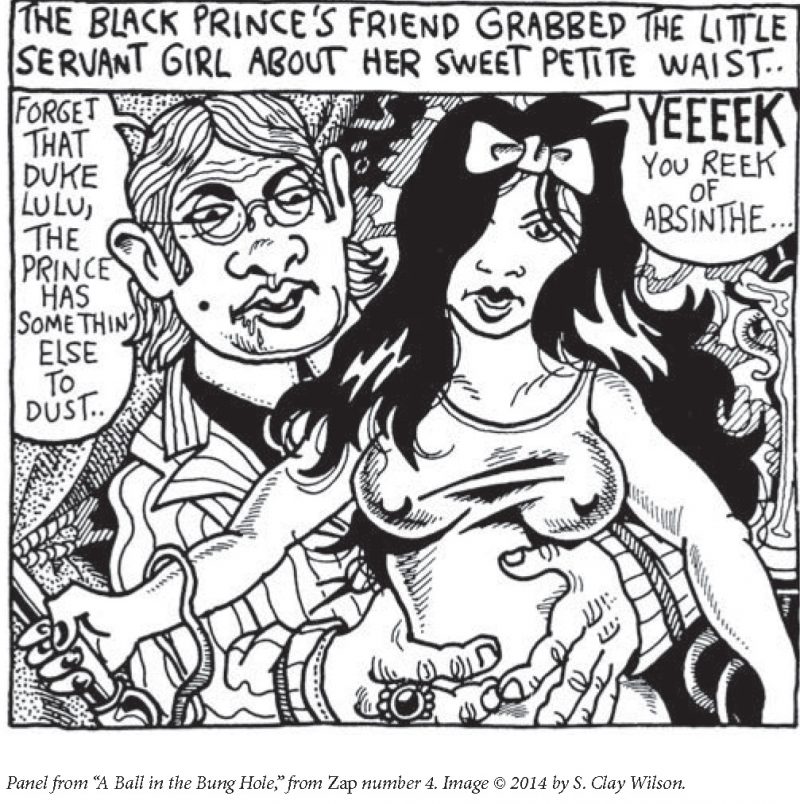

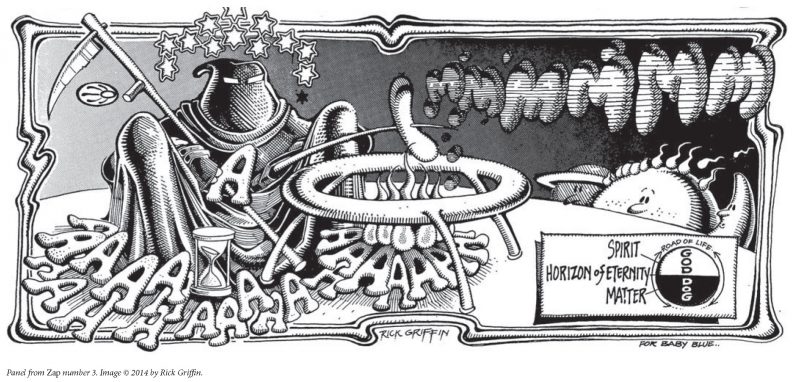

After Crumb published two solo issues of Zap, he started releasing work by other prominent creators in the underground scene—not only cartoonists, but illustrators and poster artists. Crumb published the great psychedelic designers Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso; S. Clay Wilson, the brilliant artist of the grotesque; a young hot-rodder and future Juxtapoz magazine founder Robert Williams; the epic revolutionary cartoonist Spain Rodriguez; the hilarious, underrated satirist Gilbert Shelton; and the younger, anarchic cartoonist Paul Mavrides. These artists were responsible for a large chunk of the best of 1960s and ’70s comics. By banding together to produce Zap, they allowed access to the extremely diverse potentialities of the comics medium in a single comic book. Now Fantagraphics is collecting all fifteen issues of Zap, published over a nearly forty-year span, and packaging them with the sixteenth and final issue and a lengthy oral history.

On the occasion of this publication, I spoke to Crumb, now seventy-one years old. He has produced a wide and varied body of work over the years, from his numerous one-man comic books, with titles like Despair, Uneeda, and Hup, to his hugely important 1980s comics anthology magazine Weirdo, to his most recent title, The Book of Genesis. Crumb lives in France with his wife and frequent artistic collaborator, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, not far from his daughter and two grandchildren. Crumb was a wry and funny conversationalist, generous with his answers and patient with his time. Toward the end of our talk I heard the shouts of children in the street, which signaled that it was time for Crumb to stop being an icon on the phone and once again become a grandfather to the exuberant voices outside.

—Dan Nadel

THE BELIEVER: I want to start with the history…

ROBERT CRUMB: Let me ask you something about The Believer, though. Do you know the editor? That Eggers?

BLVR: No, I don’t know him, no. Do you?

RC: No. But you know, I’ve picked up that magazine in some bookstores and looked through it— I don’t get it. I don’t understand what the point is. I couldn’t get engaged in any of the articles, I don’t understand what the approach is, what the attitude of that magazine is. It’s weird to me. Do you?

BLVR: I guess there are parts of it I like. There’s always something interesting in it about some author that I like, or something that kind of catches me. I mean it’s been around, God, maybe ten years now, or a little less— it’s a literary magazine, essentially.

RC: All right, I’ll buy that. There’re nice graphics sometimes, but I don’t know. It’s odd to me. I wonder if it sells well.

BLVR: I think it does ok.

BLVR: So in 1967 you got to San Francisco…

RC: Yeah, I arrived there in January ‘67…

BLVR: And you were 24 and married…

RC: Just in time for the human be-in in Golden Gate Park. Ken Kesey came down in a parachute. And Allen Ginsberg.

BLVR: When you got to San Francisco, as far as I can tell you’d been married a couple years. You had two completed issues of Zap.

RC: No, no, those came later. I did those in late summer, early fall of ’67. First I did that issue Yarrowstalks, you know, the underground paper in Philadelphia. This guy Brian Zahn, he came to the West Coast, I met him somehow or other, he’d seen I’d done some strips in the East Village Other printed some work of mine, and Cavalier Magazine printed some stuff of mine—so I did this issue of Yarrowstalks and then Brian Zahn said, “Well, why don’t you just do a whole comic book, and I’ll publish it?” And I thought, wow, really? That’s great! I was thrilled. So I immediately set to work on Zap Comix number 1, and it actually turned out to be number 0 later, ‘cause I sent all the original work to Brian Zahn, I did it very quickly, and I immediately started on number 2 ‘cause I was all full of enthusiasm about it. And then I never heard from the guy. I didn’t even—I never heard from him or spoke to him again. He absconded with the artwork. Fortunately I had made a set of Xeroxed copies before I sent it to him, and the comic book ended up being printed from those Xeroxes. Every printing after that has always been based off those Xerox copies, never from the original art. I tried various times to see if I could get the people that owned the original art to make good copies for me, but then they just never got around to doing it, they just couldn’t be bothered.

BLVR: To this day, still?

RC: To this day. So anyway, I set to work and I finished number 2, which ended up being number 1, ‘cause 0 was gone and all I had was the Xeroxes—and I didn’t even have the Xeroxes in my possession, I’d given them to somebody and had to get ‘em back from the guy. Later I got ‘em back from the guy, and that first issue of Zap was number 0, after number 2 came out… So anyway, I got mixed up with Don Donahue and Charles Plymell, and they printed what became Zap number 1.

BLVR: So you got to San Francisco January ’67, you were there, how’d you find Donahue?

RC: I met him through a friend. And he was really impressed with my comics. And I showed him Zap number 1 and he said, “I’m gonna try and get this printed for you.” And he found Charles Plymell who was printing poetry books. He had made these large-sized, almost tabloid-sized, scenes that were full of photo-collages, montages that he had made. And he was printing those on this little multilith press. He had only been in San Francisco a little while.

BLVR: What was Donahue like when you first met him, because he’d already published some poetry zines, he’d been around a bit.

RC: He was a mellow guy. Drank too much, was Irish, he grew up in San Francisco. I hung out with him quite a bit, actually, and he started Apex Novelties—that was his idea. And he took over from Plymell, the whole printing. He actually ended up trading Plymell a tape recorder or something for his printing press. And then he learned how to print. He wasn’t very good at it. He was very slow. I remember going over there one time and he was printing Snatch comics, when he had his printing press in the old Lowry opera house in San Francisco, which later burned down, this old Victorian place. I went over there once to see what he was doing, and he was just standing over the press—the press is going, the pages are coming out and just flopping on the floor, coming out of the press and falling onto the floor. And he’s standing there with his bottle of whiskey, just watching this. And they’re just going right into a big, random pile on the floor. And I said, “How come you’re letting them fall in a big, random pile like that?” And he said, “Oh, the ink dries better that way than if they fall on a stack. Sometimes on a stack they stain each other.

BLVR: I want to talk a little about how you got to San Francisco. You moved from Cleveland…

RC: I ran away, basically.

BLVR: You started out doing greeting cards when you were 19.

RC: I was working at a greeting card company, I lived with my first wife, Dana. I worked there for a while, and then Dana and I moved to Europe for a while, came back, worked there for a while again…

BLVR: In Europe—is that where you did the work that was published in Help, the sketchbook work?

RC: I did the Bulgaria thing. I was in Europe for 5 or 6 months, and then back in Cleveland, back to the greeting card company, and then Harvey Kurtzman offered me a job working for Help magazine—in the spring of ’65, was it? So I jumped at that, moved to New York, and, like, arrived at the office on Monday and Kurtsman was looking all down and dejected and informed me that the publisher, James Warren, had folded the magazine.

BLVR: [laughs] You were just in time.

RC: I had just got a rented apartment with Dana and moved our stuff there, so Kurtzman felt guilty about it and got me work with, like, Topps. I worked for Woody Gelman at Topps and did other odd jobs like that. I didn’t like New York, it was too tough, too competitive for me—I couldn’t handle it. Gelman he was like a big executive there. That whole section of Brooklyn, when you went to the Topps factory, the whole area smelled like Bazooka bubble gum. It was down there on 36th street.

BLVR: Right, because they were making the gum there, right?

RC: The factory was right there, the production. Everything was right there. They had this art staff there, they had a room with about a dozen people that did all the art production for the cards and all their other gimmicks that they put out. It was just such a depressed bunch of New York Jews, it was incredible.

BLVR: Well, they were all sort of washed-up cartoonists, mostly, weren’t they?

RC: A couple of them were like that, a couple were just like… a young Jewish woman that just did production work, and she was very skillful. She was so depressed. [laughs] The place was real gloomy. It reminded me of a story by Isaac Singer about some magazine that he worked for that’s all depressed-up Jews, in New York. Somewhere in Brooklyn. There was this guy in the corner of Gelman’s office, had a little cubby hole in one corner, his name was Kerry I think. He was a little Irish guy, old guy whose whole job was to sit there all day and create little gimmicks that they could package with the bubble gum. Ingenious little, like, you can take a card and fold it up into a little airplane or something. He used to work on stuff like that all day. He was a funny little guy.

BLVR: Good lord… So you worked for Topps a bit in New York…

RC: I’d take the Lexington Avenue subway to work every day and said, “Oh my God, this is awful.” I went back to Cleveland, and went back to the card company again for another 9 months, until and then I fled. And all the time I was taking LSD, and I was getting more and more alienated from this mainstream culture that I had to work in to survive, you know, and it became more and more cardboard to me. And then when I got to San Francisco—the reason I went to San Francisco is that a friend of mine from Cleveland had come back with these psychedelic posters, like a handful of them, you know, 5 or 6 of them, and I thought, “Wow. There is really something happening in San Francisco.”

BLVR: You liked the psychedelic posters?

RC: Oh, yeah. I thought, these artists are obviously inspired by LSD. I had seen visions of graphics like that, just like Stanley Mouse and Moscoso and Griffin were doing. And I said, “Wow.” And I just had to get the hell out of Cleveland. And so one night at a bar I ran into these two friends of mine, people who should have died, were gonna drive to San Francisco that very night. I just went with them. I told this other friend of mine to tell Dana—it was a terrible thing to do to her, a terrible rotten thing I did [laughs]. I couldn’t confront her.

BLVR: You were out of there.

RC: I ran away and it was awful. I was weak. And then I got to San Francisco, and I couldn’t believe what a sweet scene these people, these hippies, had going there. It was so sweet and soft and gentle and easy. Life was so easy. I thought this was like a paradise these people found here, what they’ve set up for themselves. People had these beautiful scenes in Santa Cruz mountains and in Marin County. I continued to take LSD, and I invited Dana to come out and move in with me. And then Dana got a job at an unwed mothers’ home. And then she got pregnant. So she quit that job and we went on welfare.

BLVR: The first issue of Zap went on sale in 1968. The story goes that you were out on the corner of Haight and Ashbury, selling it out of a baby carriage. Is that true?

RC: Well, Dana was pregnant, and we took them around in the baby carriage to these different stores to try to see if they would take some copies to sell. We did everything. After the printing, we folded them, stapled them. We didn’t have a trimmer, so the first bunch weren’t trimmed at all.

BLVR: How many were printed?

RC: 5,000 in the first printing that Plymell did… We tried to sell them, tried to keep a record of the sale, do the whole business ourselves. That’s the way you do it when you start on the scene. And at first all these merchants were like, “What is this? A comic book? What the hell?” They didn’t get what this was. The owner of this one shop on Haight said, “We don’t sell comic books here!” But then they kind of caught on pretty quickly, though. By the fall of ’68, though, I was kind of a name in the hippie subculture there. Happened quickly. But you things were very fluid in that time, things were loose.

BLVR: What do you mean by that?

RC: There was a lot of possibilities because there had been a kind of a cultural revolution. That left a lot of things wide open. I mean, the hippie sensibility was a very new thing; it was somewhat based on the old beatnik thing, but it was also a new thing. What LSD did to people was quite new, so the old media people—they just didn’t get it. And they tried, they tried to cash in on the hippie thing, they got it all wrong. You know, you look at all the stuff in the late ‘60s and even early ‘70s put out by the mainstream media, they’re trying to get the hippie thing and misinterpreted every which way. So if you were part of that culture and you had any kind of talent for, you know, anything—music, art—there was all kinds of possibilities. New, you know. And then you start underground, you’re never that concerned about money, you know, I didn’t care about the money.

BLVR: But you must have been ambitious. I mean, you must have had an ego and ambitions to get the work out there.

RC: Of course. I was driven—I was driven to prove myself and be recognized and to be loved, you know, wanted to be loved. All that stuff—you know, I had a painful, lonely adolescence and all that stuff.

BLVR: One of the things I’ve always wondered about with Zap is, you kind of inadvertently invented a new form. I mean it was a comic book, but…

RC: It was not a new form at all. I mean, I did not invent a new form. I actually used a very old, archaic form, which is part of the reason why all those merchants on Haight Street I think at first didn’t get it—“Well we don’t sell comic books here!” And my idea was to produce a ten cent comic book.

BLVR: You mean just like the ones like John Stanley and Carl Barks…

RC: Yeah, all the comic books that I loved. I mean, Donahue was the first one to hitch me to the reality that, you know, you can’t sell a thing like this for ten cents. You have to charge at least twenty five cents for it. You know, it’s such a limited thing, such a small thing, you’re losing money for ten cents. The printing and all the labor and all that stuff, the industrial realities. Which, you know, I didn’t know much about: business and industrial realities. Which you have to know, if you’re getting involved in that.

BLVR: But I guess what I mean by ‘inventing something new’—I mean, there were early attempts at making comic books with whatever anybody wanted…

RC: You mean hippie comics and underground-type comics? Yeah, there were a few. There was Jack Jackson’s God Nose and there were a few others like that, yeah.

BLVR: But yours somehow caught fire before there’s.

RC: Yeah, something about it really appealed to people.

BLVR: Do you think that you had an innate commercial sense?

RC: I think I did. I understood the commercial imperatives. How to appeal to some sort of mass audience, how to make a comic or a cartoon appealing—I think I understood that. Probably better than some of the other ones.

BLVR: But it’s funny that you gave yourself permission to make a comic book filled with what you filled it with, given that your major influences were… I mean, Mad wasn’t that straight, but Stanley…

RC: You mean explicit sex and all that stuff? You know, at first I didn’t. If you look at the first two issues of Zap, they’re kind of tame…

BLVR: They’re pretty psychedelic

RC: Yeah, but they didn’t get that outrageously explicit. That kind of happened after meeting Wilson. The guy was just completely unleashed, totally. I’d never seen anything like it. He was a total original that way, Wilson. Total original. No one had done that before. Ever. Ever in history, what he did. So that was a real eye-opener, and then I decided to just kind of cut loose also. For what it was worth. Part of it was we were young, part of it was shocking the bourgeoisie sensibility, just to do it for shock value, to some degree. It was like punk rock or something: a lot of that just for shock value. Go against your teachers and parents and all authority figures. Thumbing your nose at all the shit you’re brought up with, you know. Repressive, hypocritical crap, you know. So a lot of it was that. That was fun, that was fun to do [laughs].

BLVR: Right [laughs]. So why did you open up Zap to Wilson, Moscoso, Shelton and Griffin for issue three?

RC: Well, it seemed like a good idea at the time. I liked their work, and they did a psychedelic poster that looked like a comic page, looked like a Sunday comic page.

BLVR: That Family Dog poster, is that it?

RC: Yeah, it’s called ‘Sunday Funnies’ or something like that. I can’t remember if I approached them, or if they approached me, or how it happened. But I remember I really admired their work and got together with them, and they were into doing a comic, and then Wilson really wanted to get in on that too, so I said, “Sure, why not, what the heck.” And then we gradually brought Spain onto it, and then Robert Williams and Gilbert Shelton. But then this thing happened, which I was never really happy about, which was that some of them wanted to enclose Zap Comix off from any other artists, which I thought was not a good idea—I didn’t think that was a good idea. But I just kind of went along with it, ‘cause I’m weak.

BLVR: Well, you’re not that weak; you survived.

RC: I couldn’t stand up to them. Yeah, I survived, but I couldn’t stand up to those guys. Most of them are pretty macho tough guys, more than me. So I let that happen—a big mistake, big mistake.

BLVR: Why do you think that was a big mistake?

RC: Well, a couple things. One is, it immediately made us ‘the establishment.’ It made us an exclusive club of seven privileged artists. It also made it so the thing couldn’t even come out regularly anymore. It started becoming longer and longer times between issues; it ended up being years between issues. That was ridiculous! And if we’d used other artists’ work—you know, there was plenty of other good artists around—Zap Comix could have been a real forum for all the interesting, alternative cartoonists who were around. That’s how I saw it. After I opened it up to those guys, I thought, well, why not open it up to Justin Green and Kim Deitch and, you know, lots of good artists. Even some women artists. Of course, none of them liked Aline’s [Kominsky-Crumb] work much; I liked it, but Wilson thought Aline was a shitty artist, etc. etc.

BLVR: Meanwhile, it’s so ironic, now Aline’s work looks so ahead of its time. I love Aline’s work.

RC: Huh. I’ll tell her. I was always a fan; she’s a great storyteller, and very funny, very funny. But you know, a lot of comic guys—they like nice drawing, I mean the drawing’s very primitive.

BLVR: I mean, that’s why everybody hated Rory Hayes. People want it to be, I don’t know what… slick.

RC: Yeah, that’s right.

BLVR: Even in the underground [laughs].

RC: Yeah, even in the underground.

BLVR: It’s ironic.

RC: I remember Janis Joplin—when we put Rory Hayes in Snatch Comics, she came over, very serious, and said, “This is really a mistake, to put this guy’s work in Snatch Comics. This guy can’t draw, and he’s really sick. He’s a really twisted psycho. It’s not funny, it’s just psycho.”

BLVR: He was great.

RC: Oh, yeah. Loved him. He should have been in Zap Comix. Yeah, a lot of people should have been in Zap Comix. I just didn’t understand why those guys wanted to make us closed, exclusive. I mean, Wilson would say, “Yeah, man, we’re like a band, you know? We’re like the Rolling Stones or something.” I couldn’t, I couldn’t get into that idea.

BLVR: Are you fond of Zap, more than other projects of yours?

RC: I got just very disinterested in Zap, after it started taking longer and longer. Moscoso and Griffin, especially Moscoso would drag out with getting his work done. So I just lost interest. And finally I started Weirdo in ’81, you know. It was kind of a more wide-open idea of what I thought a crazy, underground magazine could be. And I maintained strict editorial control with Weirdo, which I realized I should have done with Zap—but I was too young and vulnerable. With Weirdo I just, you know… Until I got tired of it, and then I handed it over to Peter Bagge, and he pretty much kept the same editorial policy that I had. And then Aline did the last nine issues or something. But we kind of worked together on it, me and Aline.

BLVR: Those are great.

RC: Yeah, pretty much. It’s weak stuff and strong stuff in all the Weirdos.

BLVR: The thing I wanted to ask you about Zap, just going back for a second, is: over time, the stories that you put in Zap, did you draw them especially for Zap, or…?

RC: Yes, they were drawn especially for Zap.

BLVR: What was the criteria for putting something in Zap for you? Why one story over another?

RC: There wasn’t any criteria, just: ok, now it’s to time do something for Zap. Whatever was on my mind, I would do it for Zap Comix. And if another comic came along that needed some work, or if I was working on some book of my own, I would, you know… There wasn’t any particular criteria.

BLVR: Now, the artist Peter Saul told me that at one point you guys asked him to be in Zap.

RC: I did, yeah. That was way back, way back.

BLVR: And he said…

RC: “No.” There’s no percentage in being in Zap. At that time there was no nothing. When I met him the Stedelijk museum [decades later], he took me aside and he said, “You know, Crumb, there’s a lot more money in this painting than there is in doing comics. You can’t believe how much money you can sell a painting for. You can get a half a million bucks for a painting! What do you get for a comic? A few thousand bucks? It’s nothing!” He gave me a spiel, he said, “There’s so much more money in the painting racket.” He was right. Absolutely right. I like his work, though. I like Peter Saul’s work.

BLVR: Was that the only contemporary art you were interested in at the time? I mean, were you looking at other stuff at all?

RC: Not much. I wasn’t interested in much, no. Wilson was more interested in the fine art world than I was. But another artist I asked if he wanted to be in Zap Comix was this artist who worked for the Black Panthers newspaper.

BLVR: Emory Douglas?

RC: Yeah, Emory. Yeah.

BLVR: He was great.

RC: Indirectly. I asked somebody who had some connection with him if he would be interested in doing something for Zap Comix, and he also said no.

BLVR: That’s too bad.

RC: Well, yeah. I can understand why. He just didn’t want to get involved in white shit. You know, at the time they were so into seeking just a pure black identity. This all white thing just seemed like traps to them, like a snare. So it’s understandable… I didn’t ask Trina [Robbins]; she was pissed. She felt excluded.

BLVR: And so now that Zap is done, what’s the next work? Are you working on another book right now?

RC: I am, but I don’t like to talk about what I’m doing, I just like to get it done.

BLVR: And what is your work regimen every day?

RC: I don’t have a regular work regimen. I don’t work regularly, I work sporadically. I go on work binges. My life’s very complicated now, and, you know, I always have to be talking on the phone doing interviews and stuff. It’s hard to get any work done.

BLVR: Like this.

RC: Yeah.

BLVR: Just taking away from the work.

RC: And, yeah, spending a lot of time with the grandchildren and things like that.

BLVR: How many do you have?

RC: Two. I hear them screaming out in the street as we’re speaking. They’re out there screaming in the street.

BLVR: How is it being a grandfather? Do you like it?

RC: Yeah, I do.

BLVR: I wanted to ask you: part of the reason you started Weirdo, you said once, was that you felt a responsibility to comics. A responsibility to open things up. Do you still feel that way?

RC: Not anymore, no. I’m ready to leave the arena and leave it to the younger people. I’m happy to leave the stage and let them take over [laughs]. I’m old. I’m old. Comics is a young man’s game.

BLVR: Really?

RC: Oh, yeah. You’ve gotta love it, you’ve gotta be really dedicated, it’s a lot of work. There’s very little reward for the amount of work you put in, in comics.

BLVR: That’s true. That’s true.

RC: I know. That helps keep comics vigorous and authentic, though, because of that.

BLVR: Would you do things differently now? I mean, looking back, do you have regrets? Things that you wish you had done differently with your work, or books you wish you had published? Books you wish you could unpublish?

RC: Umm, let me think about that… That’s a very rhetorical question, you know? ‘Cause you are who you are, and you do things because that’s who you are. And the circumstances of the time, that’s what it allowed you to do. So I don’t know. Do I regret anything I published? Not really. Sometimes I have qualms about some of the crazy sex stuff I did, but… I don’t know, I don’t know what I think about it ultimately. Don’t know. Sometimes I look at my old work and it looks really lame to me, other times I look at it and I’m like, “Hey, this guy’s good!” You know, it’s both reactions.

BLVR: But you survived; a lot of your peers did not.

RC: Well it’s tough. It’s a tough thing to keep doing over the long hall.

BLVR: It is. But you stayed relatively sane…

RC: Well, probably partly was I didn’t abuse substances. That helped. You know, I stopped drugs in ’74 and didn’t drink much. And I still escaped into my work for decades. Though I do it way less now than I used to.

BLVR: Did having a family help? Aline and Sophie. Did that help, in a way, keep you grounded?

RC: Aline helped keep me grounded, that’s for sure. She’s ultimately a coper, you know, so she’s, like, helped me get through. You know, the practical realities of, like, my first wife and all the other girlfriends I had were totally crazy. Dana just died a week ago.

BLVR: I know, I heard. I’m sorry.

RC: I hadn’t seen her for a long time. I was relieved, in a way.

BLVR: Why?

RC: Eh, her troubles are over, you know. She had a lot of problems, lot of problems. Her health was really badly deteriorated.

BLVR: One last thing—do you meditate?

RC: Yes, I do.

BLVR: How long have you meditated for?

RC: I started in June of 1996.

BLVR: What kind of meditation?

RC: I just sit for like 35 minutes every morning—when I can, if things aren’t too crazy. Yeah, real simple.

BLVR: Has it made a difference?

RC: Oh, yeah. It’s real good for preserving sanity. It just kind of makes you detached from it all.

BLVR: Yeah, that’s good, that’s good.

RC: Oh yeah, good thing. Do you meditate?

BLVR: No, I wanna try, I’d like to start.

RC: Get busy! Get busy! I recommend it to anybody—it’s cheap, doesn’t cost anything, you don’t have to go anywhere to do it. You just have to find some quiet time.

BLVR: Did you teach yourself?

RC: You don’t have to teach yourself, you just sit. Sit down in a chair, clothes your eyes, breathe, try and relax, you know. Relax and breathe—and go from there. You don’t have to chant, or do anything, you know, just go from there. Sometimes you get drowsy, you know. You can read books about it, gives you tips and stuff, hints about how to approach it. There’s all kinds of approaches to it. But basically you don’t need anything except a will to do it and a place, a quiet place to do it. You need a quiet place. Everybody needs a quiet place.