In 2011, Sam Farber was honored by the American Folk Art Museum with the Visionary Award, a recognition of his longtime commitment to outsider art. At the ceremony he spoke sincerely about the effect that outsider art has had on his life. Since he began collecting, in 1984, Sam has played an instrumental role in bringing outsider art to the public eye. As trustee of the American Folk Art Museum, he was a driving force behind the founding of the museum’s Contemporary Center, in 1997, and the development of the Henry Darger Study Center, in 2000.

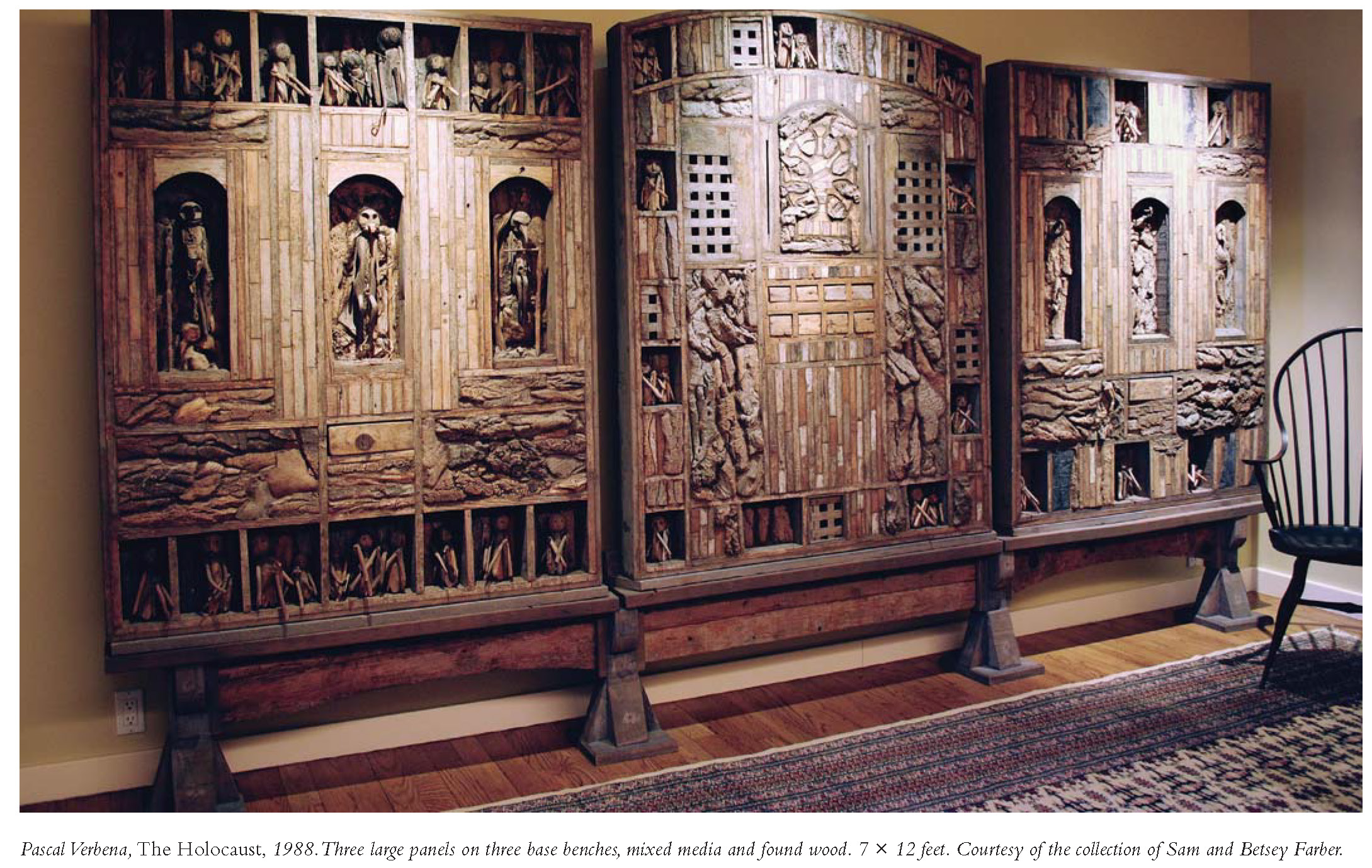

As I listened to Sam speak about artists like Henry Darger, Adolf Wölfli, Madge Gill, and Pascal Verbena, I wondered why outsider art is distinguished as a separate artistic genre. Is it because the people who created it live on the periphery of society? They are often institutionalized for mental illness, and are always self-taught. Even so, how is the art itself different from the art we see in “mainstream” museums or galleries? The more I thought about it, the more I questioned the integrity of “outsider art” as a distinct category.

When Dubuffet coined the term art brut (French for “raw art”), in the mid-1940s, he believed that mainstream art suffered from being weighed down by historical reverence and academicism: its self-awareness as art made it too much a product of culture and not enough a reflection of humankind’s knee-jerk impulse to create. He sought to find art that did not belong to any cultural system, and he compiled a collection of art that otherwise would never have reached the public eye.

Dubuffet commenced his search for outsider art in European mental institutions that had collected the art of their patients. In the first half of the twentieth century, many doctors were determined to find correlations between their patients’ illnesses and the art they produced, while others, such as Leo Navratil (at the Maria Gugging Psychiatric Clinic), observed that making art served a cathartic function for his patients, and encouraged its creation. Since then, galleries, museums, art fairs, and publications continue to study and expand the field. Those recognized as outsider artists are now exhibiting in mainstream institutions, and well-known artists are influenced by previous generations of outsider art.

In Sam Farber’s apartment, surrounded by the work of the great outsider artists of the last century, we discussed the polemic surrounding outsider art, how it became accepted as a legitimate art form, and what he sees for its future.

—Katie Bachner

I. SOME IS INTENT AND SOME ISN’T INTENT

THE BELIEVER: How were you introduced to outsider art?

SAM FARBER: We purchased a painting from the Rosa Esman Gallery by a Scottish expressionist, John Bellany. We liked it very much and really wanted to get another one. So Rosa suggested that, when we were in London next, we see Monika Kinley, who is the agent for John Bellany. When I went to Monika’s home, I looked around and saw lots of art hanging on the walls that I found compelling, and I was drawn to it. I’d never seen that kind of art before somehow. So I said to Monika, “What is that?” and she said,“Oh, that is art brut, or ‘outsider art,’ as you call it in England.” I said, “Well, it speaks to me, and I’d love to know more about it,” and that was the beginning of a two-hour tour and a lecture on art brut.

BLVR: Before this encounter, were you involved with mainstream art?

SF: Not a great deal; we had some artwork but we were not heavily involved with it at the time.

BLVR: Is there a difference between folk art and outsider art?

SF: In my mind there is a difference. They are both self-taught, but folk art, as a rule, relates to traditional art. It comes from tradition, going back to the early eighteenth century, let’s say, and the folk art of that period has continued that way. I find it to be interesting, but I think that outsider art is much more complicated, especially in terms of the depth of the individual artist’s emotional input.

BLVR: Folk art is more culturally informed—having to do more with a collective consciousness?

SF: I think I would put it differently. Folk art follows the tradition. Outsider artists like Darger and Wölfli are culturally informed, but use that to express a strong personal emotion.

BLVR: You played—and still play—an integral role in shaping the American Folk Art Museum. What kind of role do you think the museum should assume?

SF: Well, I think it is a responsibility that has been assumed since we started what was called the Contemporary Center at the museum, back in 1997. That plays more or less an equal role with traditional folk art, the idea being that they are both self-taught. That’s the raison d’être for being able to do it.

BLVR: Michel Thévoz states that “the collection of art brut in Lausanne is not a museum but an anti-museum whose goal is to place the entire museological and art distribution enterprise into question.” Did the American Folk Art Museum share these sentiments when deciding how to present outsider art?

SF: No, I don’t feel that we did, actually. Our primary goal was to introduce it to the general public, and not necessarily to set up a difference—the academic difference, let’s say—between the mainstream-art world and the outsider-art world. As a matter of fact, a lot of us believe that the majority of outsider art belongs in the mainstream category, period. And it’s being accepted in the mainstream category.

BLVR: So the whole problem that Dubuffet originally spoke of, of culture asphyxiating art, you don’t find that so much of a problem? You don’t think there should be a distinction made between the two?

SF: Well, I think that was the case when Dubuffet first started. I think, at least here in this country, it’s changed so that the “mainstream-art world” realizes that outsider art is art, whereas before it was not. In fact, in the academic world some would go as far as to say, “If there is no intent there is no art,” and I don’t think that’s true. You can’t classify art by intent. It just can’t be done. Some is intent and some isn’t intent. There is intent to make a drawing, as far as I’m concerned.

II. VISUAL VOCABULARY

BLVR: Henry Darger is one of the most important artists of the twentieth century, not just one of the most important outsider artists. Nevertheless, he is also one of the figures most emblematic of outsider art, in terms of his biography. Oftentimes his childhood is referenced in order to understand his narrative. As one of the primary collectors of Henry Darger, could you explain how his biography informs the comprehension of his work?

SF: I think that that is part of a much broader question relating to any of these artists, which is: how does the biography inform the work? A difficult question, by the way. I think that you can’t escape it. Biography is going to be there, and people are going to look at the work through the biography sometimes. I believe the art should stand on its own regardless of the biography of the artist. Does his life inform the painting? Of course, in most cases that is quite true. And, obviously, we have a history of Darger, in terms of him being put into an orphan asylum and an institution. We don’t know why he did the many things he did in his painting.

His painting was certainly a method of pouring out his tremendous anxiety, his nervous state in general. In his room, they found a number of balls of twine that were knotted. The theory would be that this kept him from going over the edge, so to speak. He was in an institution in his teens, and he escaped from it. He wasn’t put in an institution because he was developmentally disabled or anything like that—the diagnosis was, I think, that he masturbated too much or that he had a weak heart. They connected masturbation with a weak heart in those days. In any case, he was on the borderline all the time. But, luckily for everyone who likes his paintings, he was not institutionalized all the time and was free to do what he wanted to do. So I think biography certainly influences the art, in most cases, but appreciating the art because of it is not the way to do it.

BLVR: With contemporary art, the artist’s biography is mostly a cursory thing, and what informs the conversation has to do with its cultural relationship or a formal analysis. With outsider art, which supposedly does not have a relationship with culture, the conversation revolves more around the individual.

SF: Yes, but if you take a look at Darger, Wölfli—it’s loaded with things in culture. I mean, magazines, in the paintings themselves, small remarks about Penrod. Penrod is a good example. Penrod was a very well-known 1920s character in a childhood book, the star character in a series of books, so that’s culture right there. Darger calls him “Penrod” in his paintings, and he made him a Boy Scout and friend of the Vivian Girls.

BLVR: The Vivian Girls are all traced—all of the characters in Darger’s work are traced—from newspapers, magazines, and comic books.

SF: Almost all of them. Sometimes you can easily tell, because he wasn’t a really good artist in that respect. He was great in terms of composition and color. Fabulous in that respect. Amazing. Surprising. The Train Wreck [After M Whurther Run Glandelinians attack and blow up train carrying children to refuge], for example: absolutely surprising. It came out of nowhere. He has humor in his paintings—you would find Donald Duck in the clouds sometimes. All those things are part of the culture.

BLVR: I think it’s interesting that someone who is deemed an outsider artist uses the language of mainstream culture, yet his art is still looked upon as being outside of it.

SF: That’s a good point. And that’s why you can’t just say that outsider artists have no relationship to the culture. I can go back to Wölfli, for instance. Loaded with magazines. He used Heinz ketchup like Andy Warhol used tomato-soup cans.

BLVR: The 2008 exhibition Dargerism examined the influence that Darger had on eleven mainstream contemporary artists. It seems to show how much outsider art has come into the public arena, being viewed not only as legitimate art but also as a catalyst for inspiring artists who are well respected in mainstream culture.

SF: Yes, I think so. Also, one of the interesting things about Darger is that the people who came to the Darger exhibits were very young. We used to call them the Dargerites. They would come first thing in the morning. Spiked hair and the rest of it.

BLVR: Teenagers?

SF: I’d say early twenties, most of them. A lot of young people. The particular appeal of Darger to them, I’m not sure.

BLVR: The Henry Darger Study Center: is the work approached on a formal level, an individual level, a cultural level?

SF: Well, it is not taught—it is used as an example of art. The museum does a good job with that, actually. The idea being: this guy did this, I can do this. Simple as that, especially with high-school students, for instance. We have a program with developmentally disabled people and people with Alzheimer’s. With the Alzheimer’s patients you can’t really tell what is going on, but some of the developmentally disabled people react to the art very well. So it is an educational tool.

BLVR: You’re demonstrating that great art can really be done by anybody.

SF: You find it in a lot of outsider art. Artists who started just out of the blue, really. Sava Sekulic here [gesturing to a painting in the room]—Croatian, he produced thousands of works in the last four or five years of his life. What happened? He just felt the need to paint. To do something. He could have been a stonemason, he could have been anything, probably, but he felt the need to paint.

III. PSYCHIATRISTS V. ARTISTS

BLVR: Michel Foucault talks about how the gestures that distinguish madness from reason are dangerous, even though they may improve the society we live in. He speaks of the fact that there is no bridge between the sane and the insane. So the art of the insane lets us into this other way of thinking. Though there are deficiencies in one area, there can be exceptional aptitude in another.

SF: There could be. Things other than art, for that matter. But art is one of the major expressions of that, especially in institutions. It’s fascinating because when the artists are really left alone, some of the work is remarkable. When the institutions start throwing therapy into it—I guess it can be remarkable, too, but it just seems to be somebody else’s hand. You can’t be involved too much. But Hans Prinzhorn was different. He was trying to find something in the art that would work for everyone.

BLVR: Trying to diagnose through the art?

SF: Yeah. There would be one general diagnosis, really. But he managed to collect something like four thousand drawings because of it.

BLVR: Prinzhorn was one of the first psychiatrists who examined the art of people living in mental institutions. Why did he begin collecting the art of his patients?

SF: It was, I believe, 1920 when Prinzhorn started collecting. He thought that there was something about the art of the insane that would help him understand his patients. And so he amassed this giant collection at Heidelberg [psychiatric hospital]. It was an attempt to find some answers to insanity itself. He did not have an art background. And then various psychiatrists started to look at the art as well. There is a major difference between the art world and the psychiatric world. A good example is a conference I went to in France. It almost turned into a physical battle between the psychiatrists and the artists. The psychiatrists wanted to own the idea.

BLVR: What was the conference on?

SF: It was on psychiatric art and art brut. There were psychiatrists there, mostly French, and there were a few of us who were outsider-art people. There were some artists there, like [Michel] Nedjar, who lived in Paris. And it became a shouting match—sort of fun.

BLVR: What were the two sides?

SF: The artists wanted it to be called art and not be concerned at all about the psychiatric position of the various artists.

IV. REAL, PURE ART

BLVR: How are outsider artists found?

SF: Word of mouth. Sometimes they come to the gallery.

BLVR: Which in Dubuffet’s assessment would not make the artists art brut artists…

SF: Well, someone told Pascal about this guy who was making art similar to his own, and Pascal went to see him—him being Dubuffet—and Dubuffet thought Pascal was wonderful.

BLVR: So Dubuffet thought it was all right for outsider artists to seek out the art market? That thinking seems contradictory to his ideas. Did that type of thinking change once he expanded to artists in the category of neuve invention [outsider artists who are not diagnosed as insane]?

SF: Yes, that train of thought changed, and because of that, the artists understood they were doing art and wanted to sell it. The sentiment is “Oh, well, now they are commercial artists.” Why shouldn’t they be? People are annoyed by that and say the art should be pure. I find it hard to understand that. They were able to get money, they were able to enjoy themselves a bit with the money they got, even the Gugging artists. The money was put into an account for them.

BLVR: Michel Nedjar’s dolls were put into the Centre Pompidou. A couple of years later, he was put into the art brut collection in Lausanne. As we discussed, outsider artists are not being kept outside. Do you think this changes the aesthetic of the art as the artist becomes more aware that there is an audience?

SF: I think some do, some don’t. I don’t think you can make a blanket statement about it, really. I think with Darger it wouldn’t have changed a bit. I’ve seen other artists who have been more influenced by the art world when they get into a gallery, and it changes somewhat for the worse. It’s easy enough to say it changes because they’re painting for money, or they’re just turning them out now, and the original force behind what they were doing is no longer there. I’m wary of that. I can’t really say that would be true. Certainly, their painting can change. But then again, any artist’s painting can change.

BLVR: Do you find any aesthetic similarities among outsider artists? Can you distinguish an outsider artist from a mainstream artist? Is there a certain quality that seems different to you?

SF: From an aesthetic point of view?

BLVR: Sure.

SF: Well, let me ask you a question. Do you think outsider work looks different than most mainstream art?

BLVR: I believe it has aesthetic similarities, but I think it affects the viewer in the same way as mainstream art, even if it has an outsider art–like aesthetic.

SF: Well, it’s hard to say that, because we’re thinking that way. I will say that if I saw it on the wall of a gallery, I would say,“That looks like outsider art to me,” yes.

BLVR: I guess the aesthetic that I see in outsider art seems to have a relationship with how we process things psychologically.

SF: But mainstream art does that, too. I can give you examples offhand. For me, Anselm Kiefer is one: something runs very deep in there that I relate to, or my psyche relates to. Other mainstream artists don’t. Now, maybe that’s why I like outsider art. Maybe that’s why I like Kiefer.

BLVR:Why do you think there is such a growing interest in outsider art? Do you think that it parallels where we are in contemporary thought—the history of mainstream art going on one track and the history of outsider art going on a parallel track? It seems that we are at the point where they are starting to intersect. Does that say something to you about our period in general?

SF: I think that the path of mainstream art, as you were saying, is close to the path of outsider art. I think that we outsider-art people, Dubuffet and such, are responsible for building a fence around outsider art. As much as the mainstream group shut us off, we shut them off as well, and said we were something special.“This is the real art,” Dubuffet said. The very simple description of it. A friend of mine named Ladislaw Sagy, who was an African-art dealer in New York, said, “Sam, there are only two kinds of art: decorative art and art that stirs the soul.” I thought that was wonderful. It’s not quite true, but it sounds good, anyway.