The Far North of Canada is a faint concept to most people. Comprising three remote, diverse territories—the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut—it remains, in many respects, the way it always has been: sparsely populated, prohibitively cold, and outrageously expensive. Yet the Far North is not what it was. There are its natural resources, which climate change has been making gradually, indeed dangerously, available. Communications technology continues to be a significant factor in bridging North and South. Now more than ever, it is not merely southern populations, economies, and politics that are infiltrating the Far North; southern culture is staking its claim as well.

At the same time, Far North culture—in particular, Inuit art—is being introduced to a new audience in the South, for whom it often carries textbook colonial fascinations. This is not a novel phenomenon, although it is relatively recent; Inuit art has been a major dimension of the Canadian art world since the 1950s, when postwar government initiatives instated make-work projects in the hopes of stimulating the arctic economy.

A great deal of the Inuit art that has been most popular in the South does not have unvitiated ancient origins. Most remarkably, Japanese printmaking techniques were brought to Baffin Island (now in the territory of Nunavut), to a settlement called Cape Dorset, by the mid-twentieth-century Toronto artist, writer, and educator James Archibald Houston. The local population took to printmaking like gangbusters, and the market for it has grown extensively over the years—but, unlike carving, the art form is not indigenous.

A certain model of Inuit art-making has stabilized in the region: co-operatives, or “co-ops,” have sprung up, notably at Nunavut’s Baker Lake and Cape Dorset, where people come, often with no previous experience in art, to try to make a living. At present, an older generation of artists, popular when the co-ops first emerged, in the ’60s and ’70s, is seeing another generation take hold. Since Houston’s day, Inuit art has been successful in Canadian-art circles, collected by major museums, and represented by large, specialty commercial galleries in Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, and even internationally, but not until now has it seen such curious integration with practices in the South.

Two middle-aged cousins from Cape Dorset, Annie Pootoogook and Shuvinai Ashoona, have become the leaders of this renaissance. Pootoogook was nominated for and won Canada’s top prize for young artists, the Sobey Art Award, and, a year later, in 2007, was one of two Canadian artists to participate in Kassel, Germany’s documenta, one of the benchmarks for career achievement in contemporary art.

Ashoona’s work has shown widely, at home and abroad, including at Art Basel. In 2010, a short film was made about her by Canadian documentarian Marcia Connolly. Both Ashoona and Pootoogook were recently selected by curator Denise Markonish to participate in Oh, Canada, a show of sixty-two contemporary Canadian artists, which opens at MASS MoCA in May 2012.

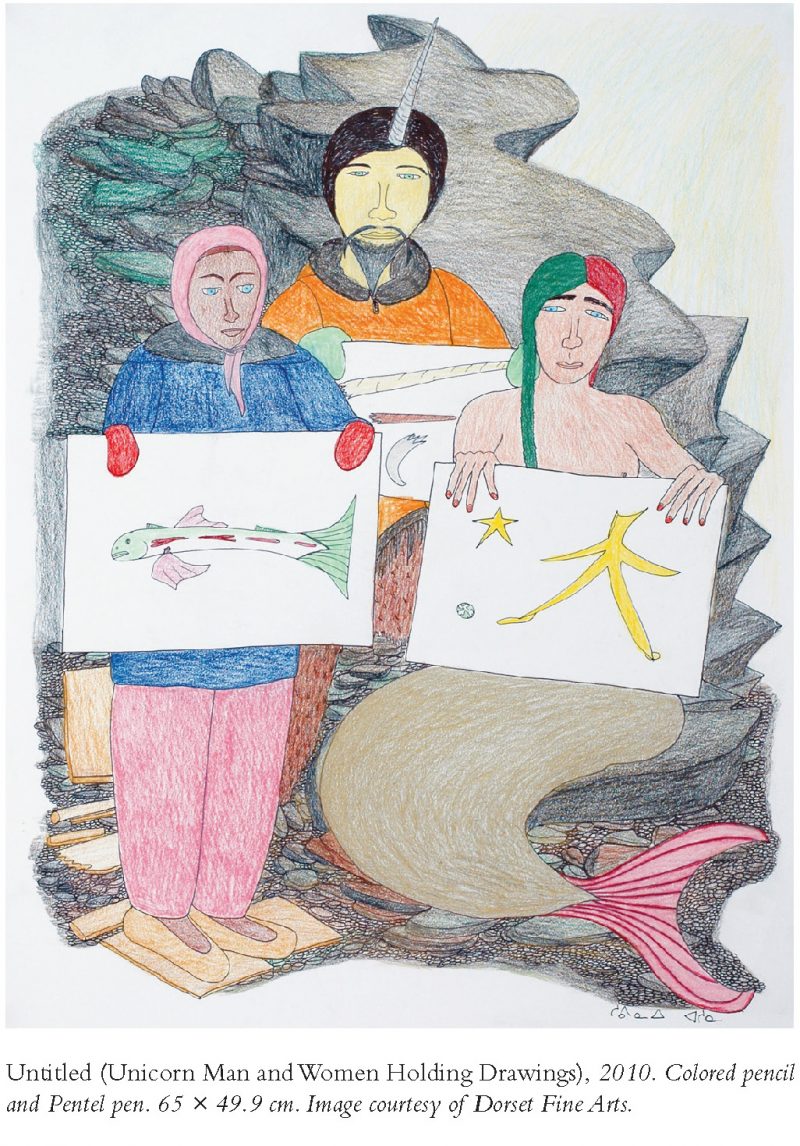

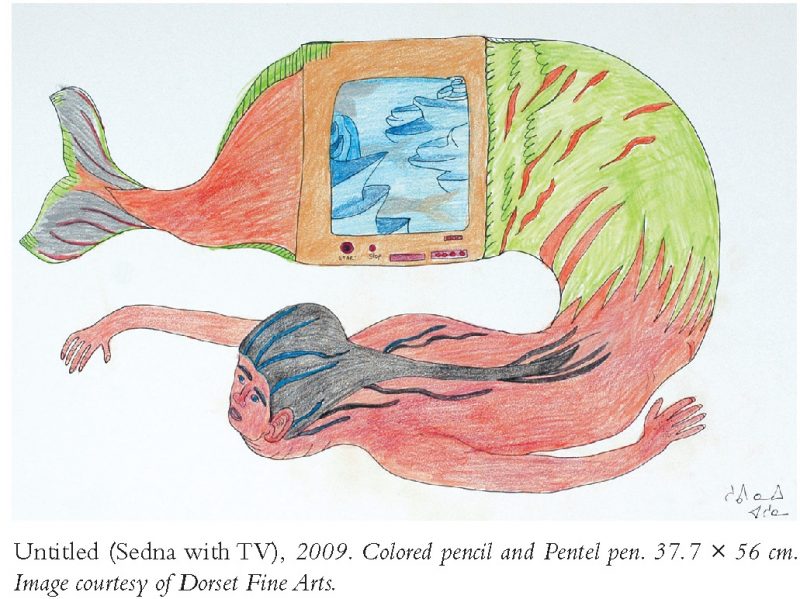

What makes Ashoona and Pootoogook so dazzling to southern eyes is, perhaps, their fearlessness and creativity, which defy the homogenous regionalism for which the Houston-led movement has become known. (Inuit art depicting ice fishing, polar bears, seal-hunts, and the like still sells readily.) Both draw in a nontraditional medium, pencil crayon. Pootoogook, whose laconic, witty work can be read as social-realist, depicts things like pornography, alcoholism, and domestic abuse. She has produced no new work since she moved south after her success, and could not be reached for an interview.

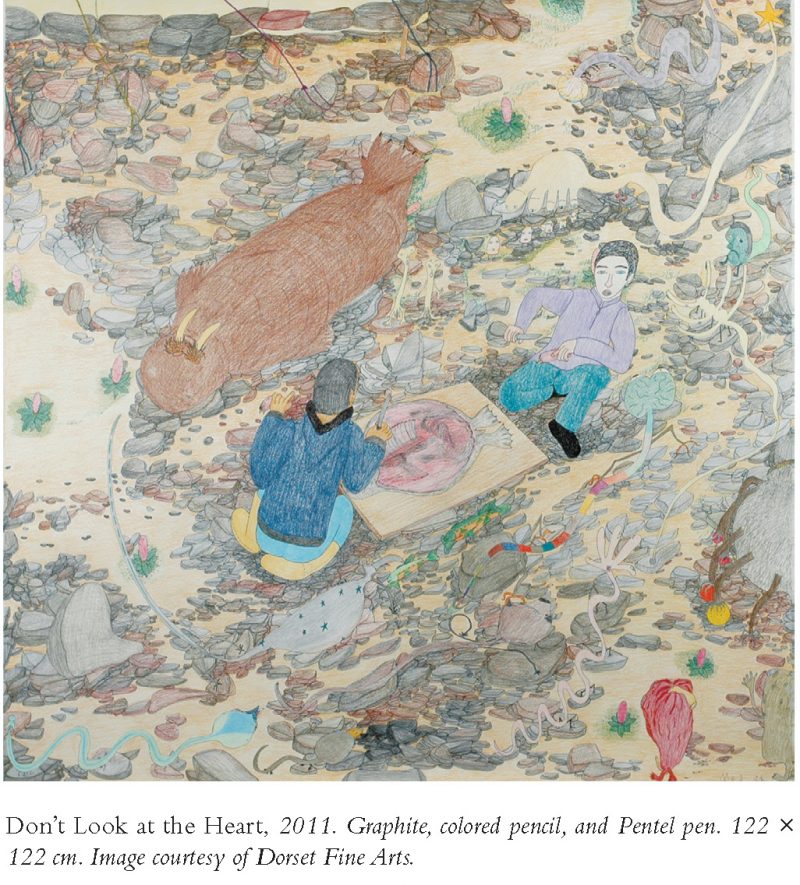

Ashoona, the subject of this interview, continues to live and work in Cape Dorset. Where Pootoogook documents the outer world, Ashoona delves into the inner. She was born in Cape Dorset in 1961 to a celebrated area sculptor—her father, Kiawak Ashoona—and to an equally celebrated graphic-artist mother, Sorosilooto Ashoona. (Shuvinai and Annie’s grandmother Pitseolak Ashoona is an iconic Inuit artist.) She began drawing in the mid-’90s—first landscapes, then increasingly colorful and phantasmic vignettes conflating personal and cultural mythologies, both indigenous and Christian. (Cape Dorset was particularly affected by the dark legacy of Catholicism and its abuse-ridden residential schools.) Ashoona works almost every day at the Kinngait studios in Cape Dorset, originally founded by Houston’s successor, Terry Ryan, where her grandmother was trained.

This interview was conducted by phone, through the arrangement of Bill Ritchie, who runs the studios. On contacting him, I was told that Shuvinai’s “ability to carry on a conversation is difficult” due to “mental-health issues.” She has “good days and not-so-great days.” When I spoke with Ashoona, she was charming; her tone was warm and welcoming, regardless of how seemingly idiosyncratic her responses were, and there was a confidence to her answers, despite the language barrier (her first language being Inuktitut) and the abundantly apparent divide in sensibility and culture.

After the interview, Ritchie sent me an eloquent email urging me to keep in mind the context of Shuvinai’s personality and artwork, and not to craft her words to suit an agenda. She is, of course, by no means a spokesperson for her people or culture; no Inuit can be, despite common southern notions of the North as monolithic, perpetuated in part by popular Inuit art and its branded, telltale symbology. Like her ancestors, she and others with whom she works do not have quite the same romantic notion of creativity that southern artists do, understanding themselves more readily as part of an economy—the nature of which, however, has shifted dramatically since Houston’s day.

Ritchie left me with these words: “It is too bad you couldn’t meet Shuvinai and get to know her, because she is a complex person. She is sensitive, caring, loyal, and tough. She’s getting older, but I have seen her wandering the winter roads in the wee hours of the morning trying to find someplace to sleep, carrying her bag of pencils and a tube of mangled paper. Lately she is troubled because her father is bedridden and her mother has health issues; they have been the glue of this family and things are about to change for the children. Good luck with your piece.”

—David Balzer

I. “I COULD GO FOR THE RAINBOW”

THE BELIEVER: Maybe we can start by you telling me about why you began to make art.

SHUVINAI ASHOONA: I started because my youngest sister told me to go down, the last time. And I found out that there was another room for that area, so I started doing what I love about my youngest sister… what she told me to do. I came over and over again. She told me to do it. I said, “Yeah.” I had no chance of saying no, because I needed something to do. At least get some money out of the papers.

BLVR: She told you to go down to the co-op and start drawing?

SA: Yeah. She lent me a little piece of paper and told me to go down to the co-op. She was leaving, going to Yellowknife—back to Bob’s place. That’s when she told me to draw.

BLVR: What was the first thing you ever drew?

SA: Just the landscape. Green grass and a little bit of rocks. That’s all I can recall.

BLVR: How long ago was that?

SA:Twenty-five years ago. I was almost twenty-five or so.

BLVR: How did you become a better drawer since then?

SA: Following the ones that are drawing around me. Drawing around them. Getting the vapor out of them. Getting the vapor out of the people who are coming back and forth in the studio. Or mainly from where we work around.

BLVR: Being part of a group of people making art. Getting inspiration…

SA: Yes. Maybe from the ones who are working on soapstones, or some people doing something else besides carvings. Maybe from that vapor—that vapor from their works—that flowing away, like the ones that are flowing, like the universe that I made a few weeks ago, like the raindrops of the universe. They’re not plugged into only one paper at all, for sure.

BLVR: You draw in pencil crayon; you don’t do soapstone carving. Why do you do drawing and not carving?

SA: The muscles of the carving, the rending of the rock, is a little bit harder than paper. They seem to be saying to me, “Forget about the carvings and do more drawings.” That’s what’s happening most of the time. I would go for carving but they say that paper is much easier than the carvings.

BLVR: Easier to do or easier to sell?

SA: To sell.

BLVR: Your drawings are very colorful. You must like color.

SA: Sometimes I do. I do, I would. I could go for the rainbow.

BLVR: You like the rainbow?

SA: Not exactly. But I do. I would do it for the people’s rainbow. For sure. The real rainbows. I don’t think I’d go for rainbows at all.

BLVR: A lot of people in the South think of the North as a place without color. Just a lot of snow.

SA: I like black and white a lot. More than anything. I do like the colors besides red; they’re better than the red ones, though.

BLVR: Black and white?

SA: Yeah.

BLVR: Those are your favorites.

SA: Yeah. If they shaped it. I go for every black and white on top of what they do. I have no eyeballs like red cars. Like those TV running-around people. That would pop up through their eyes, for sure. Everybody would be saying, “I’ve got no red eyes anymore.” Put it through invisible eyes.

BLVR: When you draw things, do you draw things that have happened to you, or just that you think of, that might not have happened to you?

SA: Yeah, sometimes. Most of the time like that. Or I keep running away from what happened next door, and start drawing over and over again, until it completely forgets what happened. Over the friendship they were having.

BLVR: So you draw things so you can forget about them?

SA: Yeah, I think so. Or at least try and rewind what they had been. Having problems. Something like that.

BLVR: And it helps you understand?

SA: Yeah, it helps. Like, the king would be around in our area, and there would be other kings, too. They make me draw and that would happen. That could happen.

BLVR: When you make a drawing of someone, do you show it to them?

SA: No, I don’t. I only draw what I’ve seen and they look like cartoons that are way, way behind what they’ve really been doing. They’d be only papers over and over again. Like newspapers. Only the newspapers would be blocking our work. Something like that.

BLVR: Do you ever look at the newspaper and make a drawing based on a story in it?

SA: Not exactly. No, I don’t think from newspaper.

II. PENNIES ON TOP OF THE EARTH

BLVR: Do you go to church?

SA: Sometimes I do. But I don’t quite believe in prayers anymore. After all, I’ve been praying the wrong way, the way I heard. But they don’t want them to pray. That’s what I heard a couple of hours ago, in the morning.

BLVR: So you used to go, but not much anymore.

SA: No, I don’t. I tried but it ended up—I’m going under the grave. That’s what happens when I try to think of the church. That’s what I sometimes think, that if

I think of the church, and go to church, I think they’re falling on my brain. That’s what happens to me most of the time. Like, I don’t want to go to the church if they’re like that.

BLVR: But there’s still a lot of church stuff in your drawings. A lot of the Bible.

SA: Yeah, sometimes I could read them all. Once, yeah, I would start reading them.

BLVR: Are there stories that you like more than others?

SA: You mean the ones that are from up there to a thousand, or those art collectors up there? Yeah, I think I’d go for that. Collectors. The sculptures up there. A thousand or eleven hundred. All the pennies up there.

BLVR: In heaven?

SA: No, not in heaven. On top of the earth where they don’t go to heaven at all. Or they go to heaven with it. They know it.

BLVR: Do you come into the studio every day?

SA: When Bill’s around, I go here every day, according to the ladies that are collapsing around us. Like, firing them around, like the younger ones. Actually, that’s not true, but we end up like that most of the time—down in the area or somewhere out there.

BLVR: Are you an older artist in the studio?

SA: Sort of. I would be. I think I’m older. Maybe I’m not. Maybe I’m not, according to her strength.

BLVR: Do people look up to you and ask you for advice?

SA: I think so.

BLVR: Do they say, “Shuvinai, is this a good drawing?” and you tell them?

SA: I don’t think so. I don’t recall saying that. I don’t.

BLVR: How long does it take you to finish a drawing?

SA: I don’t know. I’m not quite sure anymore. They’re too positive in the muscle where there’s more snowflakes. Evaporating with that, on top of the blackness. It’s snowing right now. Big snowflakes.

BLVR: Outside?

SA: The snowflakes are very, very wet.

BLVR: It’s very hot where I am.

SA: Hot day?

BLVR: Hot, humid day.

SA: Boiling day. Lots of trees?

BLVR: Yes.

SA: Green trees?

BLVR: Yes, green trees. Lots of flowers.

SA: We’ve got lots of white snow.

BLVR: Still, even in June?

SA: The snowflakes are getting smaller.

III. “TO GET OUT OF THE DRAWING PART, I’D DO ANYTHING”

BLVR: Were you born in Cape Dorset?

SA: Yes. Mom told me that I was born in a hospital, but then again, I don’t believe any word that she speaks. Against my sister swears… I’d have to go into her belly and see my mom over there. I’m a part-time breath and a part-time sister. I know which sister it is, but they’re not like that.

BLVR: Do you have one sister or many?

SA: One, two, three, four, five… I can count four or five. There’s a daughter that I got a sister of and a granddaughter that I got a sister of from my dad’s area. But then, I still don’t believe that he’s my dad, according to what he says. Well, that’s actually not true, but he goes on like that.

BLVR: Do you do other things besides drawing?

SA: Yeah, I do. I do anything for anything. To get maybe out of the drawing part, I’d do anything.

BLVR: What kinds of things do you do?

SA: I go camping.

BLVR: I don’t like camping. I find it uncomfortable.

SA: I like camping. It’s not that scary with people around.

BLVR: Do people from the South come up and visit you?

SA: Yeah, they do. They mostly do. I know.

BLVR: Do they tell you anything about your drawings?

SA: Not really. They just go through sometimes. They don’t actually go. Maybe they do but I don’t know. I’m not totally responsible for museums, or Bill’s buddies, the ones who buy them or go back and forth. I don’t know how to cope with it that much. It’s here and there all the time.

BLVR: Now that you are so good at drawing, is there a part of you in those drawings?

SA: In those pennies? No way.

BLVR: But sometimes when artists make drawings, they get sad when they have to give them away.

SA: Oh, yeah, I know. Sometimes I do. I used to think that my drawing would get sad and then the walrus would just flop out from the paper. That’s what I used to think! But I don’t think they will.

BLVR: Do you think about some of the old drawings that you don’t have anymore?

SA: I don’t think so. I don’t think I would ever miss them, even if I have to work something else besid

es drawings. Like if I have to be a coal worker, I’d never go back to the papers, for sure. Or if I have to be a ship driver, where they pick up foods, I’d never go back to the papers.

BLVR: So you never want your drawings back?

SA: Sort of. I would try to buy some of them, for sure, if I ever did. I’d go for buying them. If I really liked the ones that I drew, I’d try to buy them back. Sell it for that area, and try to buy it back. I don’t know anything about that, but I think I would try.

BLVR: But you’ve never tried, never been that attached.

SA: No, never.

BLVR: That’s a positive attitude.

SA: I only go for houses that are piled up with everything they can have! Pile them up, inside the house! I’m going for that, for sure. I know which house I like, if they’re not piling up. The one with no red walls.

IV. IT IS STILL SCARY ONCE YOU PASS THROUGH IT

BLVR: Do you read comics?

SA: Sometimes. Sometimes I start to try to read them… but they’re not humans talking back to each other, so I throw them around. I like the way they talk to each other, though, sometimes. I really like kung-fu comics.

BLVR: When I look at your drawings I also think of movies. Do you like movies?

SA: I like bad movies most of the time. Like Marcia! We used to go to movies all the time. Batman… or that one with the cigar smoke and the little kids. That one with the little kid smoking a big cigar and telling all the big boys to come down on their feet. That was a funny movie. And a bit scary. Those little boys.

BLVR: Sometimes your drawings look scary to me. Do people tell you that a lot?

SA: No, I don’t think so. But according to what I usually get out of my papers now, it looks like a spooky paper now. I’m getting used to spooky papers. [Laughs]

BLVR: But you’re laughing about it so it must not scare you too much. You draw a lot of monsters.

SA: I am drawing monsters right now. Like, I made a heart with no head, with only a penis sticking up. I tried making it little but it looked like a potato so I made it into a potato. I wanted to draw most of them but I could never recall them after I made the heart. Like it’s only H-E-A-R-T for the rest of my life; or like E-A-R-T-H.

BLVR: Do you like horror movies?

SA: Yes, yes, I do. If I like horror movies and I’m supposed to watch them, I have to go with someone that would be with me first. Then I watch the horror movie again. Like, I go scared first, then I watch the horror movie.

BLVR: You need company?

SA: Something like that. Like, it’s not that scary to be chopped off or stabbed or hang myself or shoot myself. It doesn’t look scary at all. But it’s still going. Everything’s going like that. It is still scary once you already pass through it; it’s still a scary man or lady. I think I would just relax with all the movies that are mentioned, and just see what happened. I don’t think there are any movies… but maybe I would begin to see all of those.

BLVR: Do you have a DVD player?

SA: No, I don’t think so.

BLVR: Do you go to the movie theater?

SA: We have lots of TVs and videos.

BLVR: I see. What’s your favorite movie?

SA: Aliens. Or something like that.

BLVR: That’s a great movie.

SA: There are lots of different kinds of aliens I go for. Bill’s looking at his watch. It’s almost five. I have to go.