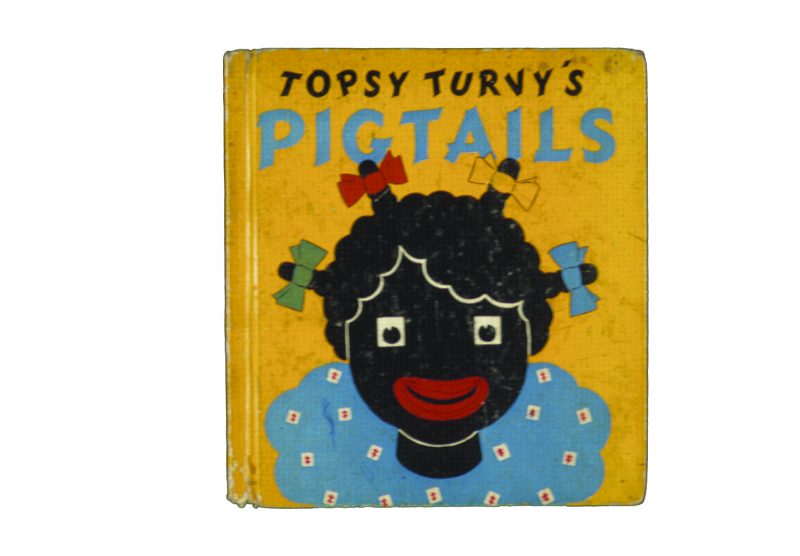

During the nineteenth century, racist imagery in the popular press was as American as apple pie. A large helping of “benign” black, Jewish, Irish, Mexican, and Native American caricatures and stereotypes filled newspapers and magazines, adorned product packages and advertisements, and illustrated books. The old melting pot overflowed with comic characters that today are considered demeaning at best, downright disgusting at worst. But back when ethnic and racial differences were threatening, and the word consciousness was barely in the dictionary, appallingly crude ethnic stereotypes were the favored commercial trademarks and cartoon entertainments. In fact, many of these depictions—which some considered a right of immigrant passage—were thought to be “friendly,” as in a friendly mascot, or as they were known in the advertising industry, “trade characters.” Yet in addition to integrating these second- and third-class citizens into society as objects of humor, the constant barrage of distorted characterizations ghettoized entire peoples according to physical and linguistic traits. Eventually, by the mid-twentieth century, much (though not all) of this mass-media stereotyping ceased, but the cultural misconceptions continued.

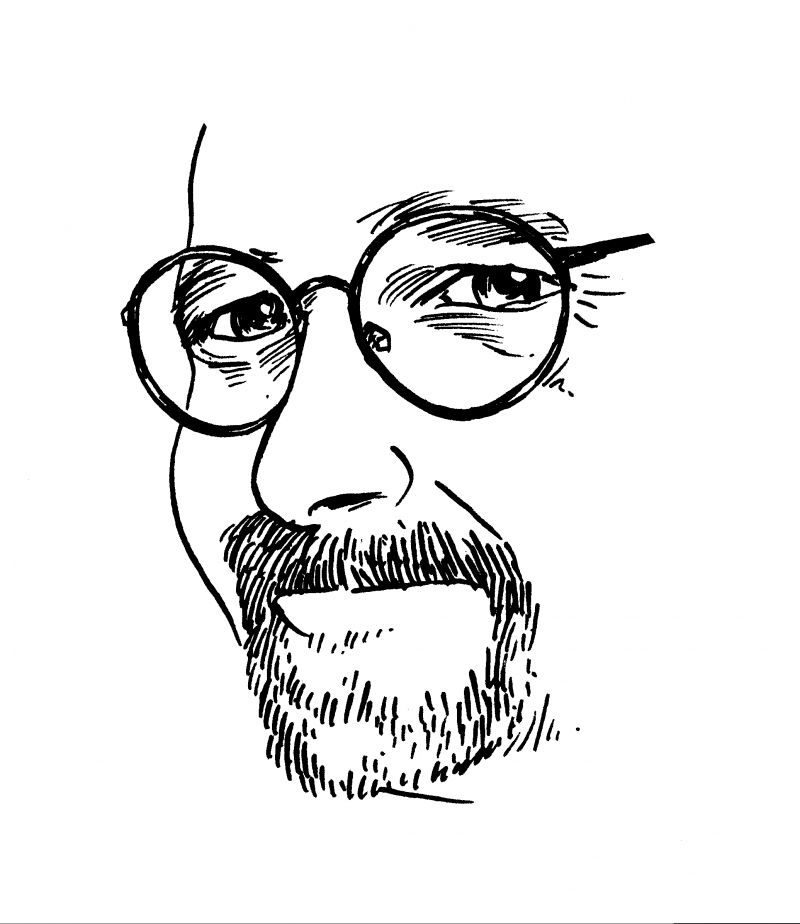

Steven Heller, an art director for the New York Times for more than thirty years (as well as a prolific author, editor, publisher, curator, and lecturer) has long collected artifacts from this “golden age” of pictorial racism. The following pages contain selections from his collection, accompanied by a conversation with novelist Susan Choi about the images, their question of their relevance today, and Heller’s impulse for collecting them. Choi, a winner of the Asian American Literary Award and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, conducted the interview over email last fall.

–Susan Choi

I. RACIALLY INSENSITIVE BARWARE

SUSAN CHOI: Let me begin by saying your collection is extraordinary.

STEVEN HELLER: Thank you. This is just a tiny sampling. What’s most fascinating is the volume of material involving “benign” racial and ethnic stereotypes used exclusively for popular art and advertising—I’m not talking malignantly racist material from supremacist groups, etc. Publishers and advertisers didn’t think twice about using imagery that would offend today, but back then it seemed as American as apple pie.

SC: How did the collection begin?

SH: It began when I was working on an exhibition of satiric art from the German magazine Simplicissimus. I noticed that among the beautifully produced and acerbically conceived anticlerical and anti-kaiser cartoons were certain matter-of-fact racial stereotypes (usually of blacks, but Jews and some Chinese were included). It made me wonder whether the U.S. had a similar comic vocabulary. Then I was introduced to a collection of “trade cards” that portrayed “Negroes” with big red lips and bulging eyes, and Jews with long hooked noses. I didn’t have to dig too much further. I...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in