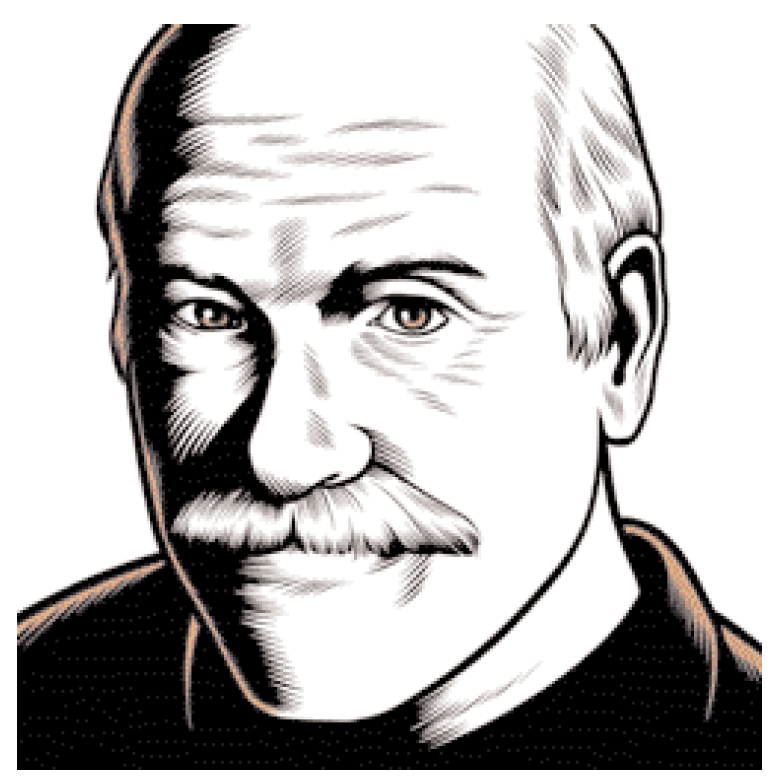

Tobias Wolff is a short story writer, a memoirist, a novelist, a father, a husband, a jazz aficionado, a hiker upon remote mountain trails, a winner of literary awards, a neophyte pianist, and the mentor of many young writers. He was born in 1945 in Birmingham, Alabama, grew up in Florida, Utah, and the Pacific Northwest, attended Concrete High School in Washington, the Hill School in Pennsylvania, Oxford University, and Stanford University, where he was a Stegner Fellow and a Jones Lecturer, and where he is now the Ward W. and Priscilla B. Woods Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences. He is the author of short story collections, memoirs, novellas, and novels, including In the Garden of the North American Martyrs (1981), The Barracks Thief (1984), Back in the World (1985), This Boy’s Life (1989), In Pharaoh’s Army: Memories of the Lost War (1994), The Night in Question (1996), and Old School (2003).

Wolff’s writing makes us recognize those aspects of ourselves that are hardest to acknowledge: our selfishness, our pride, our cowardice. But he also brings to light our potential for self-understanding and compassion—the knowledge that comes from years of honest introspection, from the desire to make sense of the decisions that shape our lives. For his rigorous intelligence and his deep empathetic understanding of humanity, he has been compared to Chekhov; he is Chekhovian, too, in the gorgeous simplicity of his language and in the way characterization gives rise to the shape of his narratives. He is a tireless reviser, a believer in the process of writing. In answer to an anxious question of mine a couple of years ago, he told me, “The only way to learn how to write a novel is simply to do it.”

This interview took place in June 2004 at his office at Stanford, where he and I had spent many an office hour hashing through drafts of my own stories when I was a Stegner Fellow.

—Julie Orringer

I. WORLD’S FAIR

THE BELIEVER: In the time I’ve known you, I’ve known you only as a writer and teacher. But I understand you’ve also been a waiter, a night watchman, a busboy; you’ve guessed ages and weights for a living, you spent several months as a reporter, and of course you spent four years in the army, which we’ll talk about later. So I’m wondering if you can guess my age and weight.

TOBIAS WOLFF: [Laughs] What I’ve learned to do with women is to go low. But I’m not going to do that today.

BLVR: Go high.

TW: I would say… stand up.

BLVR: Is it always standing up?

TW: Oh yeah. This was at a booth at the World’s Fair. [takes a moment to assess, and then guesses interviewer’s weight and age.]

BLVR: Close!

TW: I’m out of practice. Was I at least within three pounds?

BLVR: Nearly. Did you always give yourself a window of three pounds?

TW: Yeah, that was the range. Which actually allows you seven pounds, three on either side and the one in the middle. You really had to win when you were doing this, because otherwise people were just buying the prizes, which were cheap-ass little things. If you lost, they’d start looking at the prizes and thinking, “This isn’t worth my fifty cents.” So you had to win in order to get a crowd— or, in carny speak, a “tip.” When you get a tip, people keep gathering to see what’s going on. If they sense a real challenge, they’ll play, and pay. It’s like having your own private mint. They can’t wait to come up and give you money, but only if you’re already winning. I was good at it. And it was clean, there was no way to cheat.

BLVR: Was there a scale?

TW: Yeah, there was a big scale. What you’d do to get going every night is have a couple of plants in the crowd. And you’d have a line of patter. If there was a pregnant woman, you’d say “Come on in, we’ll weigh the both of you for the price of one!” You lay down a steady line to bring the crowd towards you and get a nice tip built up. It was hard to get it going during the day. Sunlight is not conducive to the mob mentality you need to create. But at night, under the carnival lights, with people screaming on the rides—it was a snap to pull in a crowd. I had a blast that summer. I’d lied about my age and was hanging out with all these old carny types.

BLVR: How old were you?

TW: I was sixteen.

BLVR: Where was it?

TW: Seattle’s World’s Fair. The rather squalid carnival section, not the Wonders of Tomorrow, the culturally edifying part of the fair.

BLVR: Were you home on break from school?

TW: I was between years at boarding school at the time. When I got home I needed to scrape some money together to make up the shortfall of my scholarship and also to come up with my train fare back East. I started off working at a coin toss. Very quickly I figured out that the age-and-weight gig was much better. I had a friend over there and he segued me into the age-and-weight-guessing business. After the fair broke up in the fall, the carnival was headed on a big swing through the country, attaching itself to various state and county fairs. I was sorely tempted to stay with it; I’d met so many characters and was having so much fun. But I had just enough sanity to know that was probably not a good idea.

II. THE THEATER OF HUMAN FOLLY

BLVR: When I read the initial excerpt of Old School that appeared in the New Yorker, I thought back to “Smokers,” your first published story, which appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in 1976. In both stories you perfectly portrayed the ways in which we manipulate the truth to our own advantage. What was it that pulled you toward that material?

TW: When I went off to boarding school, I already knew I wanted to be a writer. This might sound unlikely or at least opportunistic, but when I got there I knew that someday I would write about that place. It was so different from anything I’d experienced before, and it was such an intense wash of experience that at the time I could hardly parse it out. But I knew that someday I would. I remember discovering Salinger in my first year at that school because everyone was passing him around, still. The school he’d based his own recollections on was just down the road from us—we used to play them in sports—Valley Forge Military Academy, which he calls Pencey Prep. The book was forbidden there. The students were not allowed to have it, so of course all of them had read it. It was like a required text. I thought, “What idiots!” Can you imagine that? Anyway, it had a local notoriety, in addition to being interesting on its own. I laughed my ass off at the book when I read it, I enjoyed it so much. Of course I saw certain facets of life at my own school pictured there, but I was also very aware of some fundamental differences. By and large, the masters and boys at my school were not phonies. There was a sort of strange high-mindedness there, which I now understand to have grown out of a certain Anglophile tradition, and which was easy to satirize. Nevertheless, it was different. Salinger could not have written his novel about my school. But by the very act of reading it and correcting for it even as I read it, the seed of Old School was planted.

I have always loved reading school stories. I don’t know why, exactly, but I do. I love William Trevor’s school stories; he’s got one in every collection, sometimes two. And there’s the section in Eminent Victorians where Strachey talks about Dr. Arnold, Matthew Arnold’s father, who was the headmaster of Rugby School. It’s fascinating as an essay on education, and also very funny. Orwell’s Such, Such Were the Joys. School is a fantastic theater. A lot of writers certainly have found it so.

BLVR: It must have something to do with being in transition between childhood and adulthood. That’s fertile ground for narrative. But in a way, being at boarding school also seems akin to being in the army. Both situations are bound by strict rules and codes of conduct.

TW: Exactly. They’re both closed worlds.

BLVR: How does that affect the writing?

TW: It’s akin to the advantage a poet has in consenting to working within a form. As a writer you begin with infinite freedom, and then you must immediately start hemming yourself in.You have to choose a genre, you have to choose a voice that precludes using other voices. You have to choose a time that precludes other times. Part of the beauty of writing about the army, or such worlds, is that they offer you an enclosed theater of human folly, of human aspiration and formation.

BLVR: One of the particularly notable aspects of your school’s culture was its focus upon the literary world, its love of writers, and its idea of the writing life as something to aspire to. Did you know that about the school before you went there, or was it a fortunate coincidence?

TW: It was a fortunate coincidence. I hadn’t been there two months before Robert Frost came. He was revered in the wrong ways by the teachers I’d had up till then, because they saw him as a Hallmark card writer, which, I’m afraid, is what we were taught good writing was— uplifting sentiment.

BLVR: He is actually quite a dark poet. [“From the time when one is sick to death,/ One is alone, and he dies more alone.”]

TW: Oh, God, he sure is. He’s a tough poet. And complicated. Not overcomplicated or perversely complicated, but he is complicated. And yet there is that face of his work which is deceptive, and can allow you to read him simplistically, and that is a great mistake. Before a visiting writer came to the school, [the masters] had us read this person’s work, and they introduced me to a different Frost than I had been reading before. So when he arrived, it was an extraordinary experience, really. I had never seen a real writer before—certainly not one of that Olympian stature. He was the great American poet then. And indeed he went on to read at Kennedy’s inauguration, as you know; he traveled to Russia on a goodwill mission, met with Khrushchev. It attested to the position a poet could have in society—bringing the vision of the world of poetry into the world of affairs. You just don’t see that anymore. Is there anyone like that now? I guess Robert Pinsky would come about as close as you can get. Frost was very interested in politics. If you read his letters, you find he had lot of ideas about education, too; he’d been a school teacher. Some of his ideas were really cranky, and mischievous. He would advise young people to leave school and go off to strange places like Brazil and Kamchatka.

BLVR: Did he talk about that at the Hill School?

TW: Not to my knowledge. I ran across that in a book, a little monograph called Robert Frost as a Teacher. Then there was something in the Lawrence Thompson biography that confirmed it. Frost was very, very mischievous, and manipulative. But I’ve taken the long way around the barn here: no, I didn’t really know about the literary nature of the Hill School.

It’s funny—I just met a guy the other day who said, “That school you wrote about—was that the Hill School?” and I said, “Well, I did go there, and it was partly drawn on my experience.” And he told me how he went to be interviewed after a hockey game at Hill— he wanted to do a postgraduate year there. Our headmaster was the hockey coach, so he went to talk to the headmaster after the hockey game. He’d had his nose broken by one of our hockey players. They were very rough, even then. And I said, “Well, he would have loved you if you’d gotten your nose broken by one of our players. That’s your badge of honor. You’re in.” But when he went up to the headmaster’s study, William Golding was there and the two of them were talking and drinking, just totally shitfaced. He did indeed get in and chose not to go, after all—he got into some good college and went there instead. But here’s William Golding lying back with our headmaster, who’s a very literary guy—used to publish essays about education in Life magazine and places like that. He taught the senior honors English seminar every year. A very smart guy, widely read, advised the school literary magazine. If a kid was disgruntled about not getting his work published he could submit it to the headmaster, who would look it over and give him some comments, to help him do a little better next time.

BLVR: Did you do that?

TW: I did. Boy, I didn’t like what I got back. He really gave it to me. He was right. I didn’t want to know it at the time, but I certainly recognize the truth of his criticisms now.

BLVR: What were his criticisms?

TW: Lack of specificity. This woolly idea that the less you say about a person or a place or a situation, the more universal it will seem.

BLVR: We’re really drawn to that idea as young writers.

TW: Yeah, because it’s so easy. We like the symbolic. It’s very seductive when we’re young.

III. THE COMPANY OF OTHER WRITERS (OR, THE COMMENTS THAT DISTURBED ME MOST WERE THE ONES THAT WERE TRUE)

BLVR: One of the ideas I found particularly compelling in Old School was the notion that as young writers, we have some need or desire to be taken up by more established writers, to be introduced into their society—to shake the hands of writers who have touched the hands of other writers. Can you talk a little bit about how you developed that idea in the book, and also about how that was part of your own experience as a young writer?

TW: I was certainly conscious of the lore of writers. Even before I actually read anything about it, I was aware that Hemingway had been brought along by people like Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound and F. Scott Fitzgerald. I mention Hemingway because he was the focus of my interest at the time. As I read writers’ biographies later on, I noted that many of them met other writers and received help from them. Maupassant was a writer I loved; I read a biography that talked about how Turgenev took him up and put him through his paces. It’s a natural enough thing. Part of what my novel concerns is the way this boy is trying to move away from the orbit of his own father. He has decided—rather unfairly—that it isn’t satisfactory, and he is looking, as you do when you abandon one father, for another. That blessing touch he’s after gets embodied for him in literature. He’s looking for that hand to fall on his shoulder, that anointing. Of course we discover as we get older that it doesn’t work that way.

BLVR: In your experience, how does it work?

TW: Seldom the way it seems. For example, it’s known that Sherwood Anderson helped Faulkner along. Well, yes, he did—he sent a novel of Faulkner’s off to his publisher, but did so only under the condition that he didn’t have to read it. He didn’t read the book! He didn’t want to read it. He never read it. A funny story. Anyway, writers when they’re young tend to seek the company of other writers—some community of writers with whom they can share their work and get a response to it. I would imagine that the competition between Greek playwrights served as a kind of workshop. They were certainly aware of each other. They lived in the same town, or polis. Literature has always been written under the scrutiny—in the presence, if you will—of other writers. This idea of the writer as the figure isolé, it simply doesn’t ring true to experience. You will feel the discipline and presence of other writers through the books you read, if nothing else. Influence is inescapable.

BLVR: In your own development as a writer, you spent some time as a Stegner Fellow and then as a Jones Lecturer at Stanford. How did that affect your work?

TW: I was thirty when I came here, and I’d been writing on my own. I had never given my work to a roomful of other people and had them mark it up and tell me what they thought of it. It was kind of a shock, really. Some of what I got back was silly stuff, I thought. But the comments that disturbed me most were the ones that were true—the ones that pointed out things I was doing that I wasn’t aware of, for good or ill. There were some good critics in that workshop, foremost among them Allan Gurganus, who is also a wonderful writer. Allan was very humane but truth-telling as a critic, and very good at catching tics he could tell you weren’t aware of—tics of language, of manner. We had the same standard of writing, which was that every word should count, but I wasn’t as far along in living up to that standard as I’d hoped I was. The workshop was very useful in helping me see what I was doing, making me more self aware, to the point that I kind of had a hard time writing for a time after I got here. I did it, but the self-consciousness has a constipating effect at first. Then you drop those habits and you’re off again. I wouldn’t undo that experience for anything. It was infinitely useful to me.

BLVR: I think there’s something essential about learning the nitty-gritty, the craft of writing—it helps you make rather large leaps in your work. But it does sometimes have a stymieing effect. I felt that very much at Iowa, when I was in Frank Conroy’s workshop. He taught us so much about craft all at once that every time I sat down to put words on the page I felt a barrage of rules descending upon me. But eventually the craft becomes second nature, and the work becomes stronger for your having learned it. People talk about whether or not writing can be taught—that seems like one of the things that can be taught.

TW: I came to Stanford with some very ambivalent feelings about joining a workshop. For one thing, before I came here, I often wrote as a kind of subversive activity, something done in spite of the distractions that life presented, other jobs obviously being among them. Then there were personal relationships that seemed to represent a kind of obstacle to writing. At the Hill School and later at Oxford, writing was obviously valued but they didn’t do workshops—you wrote on your own, as an individual expression, something done almost in spite of the school. Because they asked so much of you in other ways, you had to steal the time to do it. I wrote even when I was in the army—not in a disciplined way, of course, considering the life I led.

BLVR: You were working on a novel.

TW: Yes, I was working on a novel. It wasn’t any good, really, and probably couldn’t have been, considering the halting way in which I was forced to write it. Nevertheless, I always felt as if I was getting over on them when I was writing, you know what I mean? I wasn’t supposed to do it, and that made me want to do it. When I went to Oxford, after I got out of the army, the university had no interest in creative writing at all. They would have laughed at the idea of a creative writing workshop as part of the university curriculum. I wrote a novel when I was at Oxford, and I did it in spite of my studies. And I did it again when I was working at other jobs. I always wrote outside of the realm of what anybody expected me to do. It wasn’t an approved activity. And I liked that about it. It gave it a flavor, let me put it that way. In some ways, that flavor was essential to the activity itself—that defiance, almost. So to suddenly enter a world where it was the expected and approved and institutionally encouraged thing—! I was really worried that I wouldn’t be able to write at all. In some ways that happened, but more because of the self-consciousness than because of anything else. I was old enough to know that I didn’t have time to waste, so when I was given the gift of time I used it. Nobody taught me lessons in craft as such. It was more a question of learning to be a good reader of my own work, and of other people’s work as well. Not just the writers in the workshop, but more canonical writers. I think the great use of the workshop is that it teaches you to be a good, close reader. Not to read through the lens of an ideology, or the theory of a self-enclosed world of language, but what’s here, what’s right in front of you. Attend to it. What does it say? What are these words doing? What is the form of this piece? Why this form rather than another?

And the workshop also teaches you to think about human problems. It’s not about craft for me. If it were, it wouldn’t be interesting. When I’m talking with my students I’m really interested in the human springs of a story—what is there in the necessities of this particular character that produces this narrative? What has mattered to the writer in the writing of this story? We try to understand those things, because craft without them is exercise. As you know from having been in a workshop of mine, I don’t assign exercises. I think that each time out should be a swing for the fences. Don’t do base-running drills. You can do those on your own time. The experience of reading other people’s work with that kind of attention, and then having your own work read with that kind if attention and reported to you in detail, even by voices you don’t agree with— even in your resistance to criticism you are educating yourself about writing and about your own writing. And if you don’t end up becoming a writer, it’s still got to be good for you.

BLVR: Because it increases your understanding of how the human world works.

TW: Absolutely. And how all our experiences and memories, in order to become intelligible and useful to us, must be shaped in some way. We impose a form on experience; there’s no other way to live. We don’t have a choice about it. We do it. But why do we do it the way we do it? Why do we choose one form rather than another?

IV. ONE HAS TO FACE THESE THINGS

BLVR:A number of critics have mentioned that there’s a certain moral structure embodied in your work. How would you describe the way you arrived at your own sense of morality in fiction writing, and how did it affect the way you tell your stories?

TW: Well, I’m not sure but what the experience of reading and writing fiction is what gave me a sense of morality, more than anything else, because it helped me think out and objectify the question of character. In our everyday lives, we’re mostly lost in the soup of ourselves. Where are we going to stand to see ourselves? We have to achieve some vantage point, and the continual experience of being inside oneself doesn’t give you that. The vantage point must be different for different people. For some it’s religion. I wouldn’t equate religion and literature; I wouldn’t want to make a religion of literature, it doesn’t function well as a religion—but it does offer a place to step outside yourself, as much as one can, anyway. So much of what I’ve come to think of as my character has been the result of my recognizing in other stories aspects of my own experience and my own inclinations, bad and good. That kind of heart-rising-to-heart you feel sometimes when you read, even if you’re embarrassed to admit what it is that you’re recognizing—you achieve in that way an escape from the imprisonment of the self.

BLVR: I was thinking about In Pharaoh’s Army. The narrative tone throughout the book is self-effacing and often very self-critical. The scene I keep coming back to is the one in which you’re about to be released from service and your replacement has come in—he’s very self-important, a real jerk, and he thinks you’ve failed in your duties in Vietnam—and he’s trying to direct a helicopter to land in a space that’s too small, and you decide not to deter him, and the result is that a lot of people’s homes are destroyed.

TW: Yeah, these little makeshift shelters they’ve thrown up.

BLVR: In that scene, and throughout In Pharaoh’s Army—really, throughout all of your nonfiction—you avoid one of the dangers inherent in memoir, which is that the memoirist will portray himself as being larger or more humane than we suspect he actually was, or that he’ll draw a veil over his failings. It seems to me that in your work, in a sense, you do the opposite of that.

TW: You know, that’s a really astute point—when you say “the opposite of that.” I think that, indeed, I may have sometimes exceeded what was required in self-revelation, especially of weakness and vice. I wanted so much not to do the kind of thing Lillian Hellman did in her memoirs, which was to constantly show herself in the most heroic light: always the smartest person in the room, always the one with the integrity. There are any number of memoirs like that. They seem written to show what a wonderful and superior person the writer was. Well, I know I’m not. On the other hand, sometimes I wonder if in doing this—in making a vow to myself that I would not be any easier on myself than I was on anybody else I wrote about—if I didn’t sometimes go too far in the other direction. That is, I think if I were writing such a book now I would be a little more understanding of myself, as I try to be of other people. Not in a sappy way, not in an exculpatory way; one has to face these things. But I think, perhaps particularly in This Boy’s Life, the hand may have fallen a little to heavily on the narrator. Anyway, in my anxiety not to make a special pleading for myself, there was a danger—I might have been a little harder on myself than I needed to be in the interest of being truthful.

BLVR: Do you think that the tendency to be hard on yourself in your memoirs translates to the tendency to be hard on the protagonists of your fictional narratives?

TW: I hope not. I do write, as indeed most writers do, about things that have gone wrong. There’s not much of a story if things have gone right. Stories are about problems, and not the kinds of problems that result from a safe falling out of a window, but from somebody having a choice and having a problem with that choice, and then the series of consequences that follow from making that choice. To portray that honestly is to show the way people parse out their choices, and self-interest naturally comes into play. It isn’t so much a matter of wishing to be hard on people as wishing to be truthful. If there’s a moral quality to my work, I suppose it has to do with will and the exercise of choice within one’s will. The choices we make tend to narrow down a myriad of opportunities to just a few, and those choices tend to reinforce themselves in whatever direction we’ve started to go, including the wrong direction. Our present government likes to lecture us on the virtue of staying the course. Well, maybe it’s not such a good idea to stay the course if you’re headed toward the rocks. There’s something to be said for changing course if you’re about to drive your ship onto the shoals.

BLVR: Old School seems to a large extent to be about evasions of truth—about the characters’ evasions of the truth with regard to religion, social class, and personal connections. I was fascinated by the way that theme developed across the various narrative threads of the novel.

TW: It’s not so much about the evasion of truth, which has an active quality. A lot of what happens to this narrator grows from an accumulated sense of fraudulence. For example, you mentioned the question of religion. He doesn’t really lie about that at all. What would be his lie anyway? He feels like he’s lying because he’s not telling people his father was Jewish—something he’s just discovered himself. Yet he has no Jewish relations that he knows, and he hasn’t been brought up at all in this faith; he was brought up in another faith altogether. Even under Jewish law he’s not Jewish. Mostly he feels himself to be Jewish because he’s not saying anything about it. It’s what he keeps secret that he feels to be truest about himself. His sense of holding something back gives it an obsessional character, and, in that sense, confers an imaginary identity upon him. He does this with other things too. He doesn’t really lie—and in fact no one would be that interested anyway. They may not be as fooled as he thinks they are, either. When he finally publishes his story it’s no big deal to anybody. It’s kind of like, “I thought that all along.” It really doesn’t seem to come as a great revelation to anybody.

BLVR: When he publishes his story—

TW: —that isn’t his story

BLVR: That isn’t his story, yes, that’s when it comes out that his father was Jewish. And it seems there must be a connection between this suppression of his Judaism and his sense of the unacceptability of his social class, too.

TW: That’s right. But again, he’s not entirely to be trusted in this matter. He intuits that there is something, some spirit in the school, that does not fully accept Jewish boys or boys of a different social class. But then he admits that never once has he ever heard anyone say anything to that effect or behave in that way. So where is that coming from, really? I mean, it probably is, in fact, partly coming from the school—but I think it’s also coming from him. He’s conspiring with the school to produce this feeling.

BLVR: Did you understand that aspect of the character when you began the book, or was it something that came out of the writing?

TW: I understood it when I began the book, though I didn’t understand just how pervasive it would be. Certainly this character takes it farther than I ever did, but again it’s a question of recognition. In writing a book, you can use things you recognize in yourself as points of inspiration. He’s playing out on a large scale aspects of myself that I played out on a smaller scale.

BLVR: And you chose to write the book as a novel rather than as a memoir.

TW: Oh, God, yes. I always knew it would be a novel. First of all, nothing interesting happened to me at my school. Yeah, we had Frost come, but Ayn Rand never came, and Hemingway certainly didn’t—nor did he ever agree to. But these were the writers who were most influential on me. The writing competitions in the novel were largely an invention, too. I wanted to write about vocation, and I wanted to write about influence, and since I’m a writer, the influence I wanted to home in on was literary influence, and how it works—the omnivorous, ruthless way we consume and reject influences when we’re young, the trail of dead writers we leave behind us as we progress. Most of the boys at the Hill had read Ayn Rand. At the girls’ schools, they were even more into it than we were. At the dances we would have, I remember endless conversations with girls about Ayn Rand—they were really big-time into her. After all, she was writing about women who ran railroads, and nobody else was doing that. I mean, look at the women in other fiction at the time, popular fiction. And at that age, you know—it’s a rare reader of fifteen or sixteen who is aware of the cheesiness of Rand’s style. You’re quite apt to get caught up by its very partisanship and by the heat of her own beliefs, which so animates all her fiction.

BLVR: Were you in high school when you began to reject those ideas?

TW: More just after. The narrator comes to his senses before I ever did, because you accelerate things in a novel. Again, it’s the sense of form that compels it. It can’t just be “and then, and then, and then,” endlessly. There has to be a decisiveness to achieve literary form. You’re giving an impression of life, but you can’t actually record it just as it happens or it dissolves into mush.

BLVR: I’m curious to know more about your experience of writing the novel—how it was different from writing those early longer, novelistic memoirs, and perhaps even from writing The Barracks Thief, which is sometimes classed as a novella but which feels to me like a novel.

TW: The Barracks Thief is a short novel, but it was originally written at novel length. I’d also published another novel much earlier. It was never my wish to represent Old School as my first novel; I always have to set the record straight on this. Back in 1975 a novel I’d written at Oxford was published in England and was going to be published over here by Macmillan, but for reasons that I still don’t know, it fell through at the last minute and was never published in the U.S. Thank god, because after it was published in England I withdrew it from circulation. When it came out, I realized it was awful. I had thought it was good, but somehow the light came on when I actually read it again.

BLVR: What was awful about it?

TW: Oh, it was just terrible, just an embarrassing book. It’s like a first draft of a novel. I learned something, no doubt, in writing it—made a lot of mistakes I wouldn’t repeat. I do indeed wish it hadn’t been published, and I never name it on my list of publications, and that was thirty years ago. My next book didn’t come out until six years later, a collection of stories. I’ve always considered that my writing life really began with that collection of stories, not with the novel. I never mentioned it to my publishers, it was never listed in any of my books. I never thought to mention it to anybody. My own editor didn’t know I had done it, so when they made up the publicity for Old School they said it was my first novel. In each interview I’ve had to correct that. Having said all that, I don’t know how to characterize the difference. I could give you a trite answer about how when you’re working on short stories you do know they’re going to end sometime, and how when you’re writing a novel you spend years deepening your experience of the characters and the world you’re writing about. But also a kind of anxious wonder sets in as to whether or not you’ll really finish it, whether it will be any good, whether all this time will have been wasted— and we all hate to waste our time.

Everything I’ve written, including this book, has seemed to me, at one point or another, something I probably ought to abandon. Even the best things I’ve written have seemed to me at some point very unlikely to be worth the effort I had already put into them. But I know I have to push through. Sometimes when I get to the other end it still won’t be that great, but at least I will have finished it. For me, it’s more important to keep the discipline of finishing things than to be assured at every moment that it’s worth doing.

BLVR: Sometimes it seems so hard to hold off the skepticism.

TW: You just learn to do it.

VI. WRITING ABOUT WAR

BLVR: You’ve taken on the subject of war in both your fiction and nonfiction; what were the challenges it posed for you?

TW: The hardest thing about writing about a war you’ve been in is that you’re terrified of getting it wrong, because of the people who have suffered such losses—and I’m not just talking about Americans. I’m talking about the Vietnamese, too. There were a million Vietnamese killed, most of them civilians. You’re aware that whenever you write anything about war, even with the intention of showing what it’s really like, you’re covering it with that inevitable glamour that war has for people, except when they’re in the middle of it. This last April, when those troops headed across the desert in their tanks, doing those “We’re gonna go get these guys” interviews, like kids going to the next town to play a basketball game or something—those were the same kinds of things we were saying when we first went over. And now—talk to them now.

BLVR: A lot of people have drawn comparisons between what’s going on in Iraq right now and what went on in Vietnam.

TW: It’s very different, really. I don’t think the comparisons work except in the folly of the enterprise and the mendacity of those who led us into it, and the willful blindness to reality, and the failure to appreciate anything about the country that we were going into, and the failure to seek out people who knew what the situation actually was, people who could plan reasonably for it, and maybe even decide not do it on the basis of what they learned. To start off with their minds made up, and to allow only those things into consideration that further strengthened decisions made in utter ignorance—in those ways, yes, it’s similar. But on the ground, in the place itself, they could not be more different.T o begin with, there was no civil war going on when we went into Iraq. There was not a legitimate movement, a nationalist liberation movement we were going in to oppose. There was a despot, an evil regime in charge, unambiguously so. That didn’t mean that we should’ve gone in. There are a lot of despots and evil regimes in the world. I don’t know why, for example, we didn’t take measures against Charles Taylor before we did, while he was slaughtering his fellow countrymen by the hundreds of thousands. If that really is the reason we went into Iraq, we should have been doing it elsewhere, with others.

BLVR: Of course, that wasn’t really the reason.

TW: No, it wasn’t, and it’s not even the reason we were given. For them to appeal to that as their justification now is very dishonest. They fudged it, and now they’re paying for it. At this point, we are actually creating a resistance that was not there before. In that way, I guess it could come to resemble Vietnam, but it will be a Vietnam of our own creation. Won’t that be ridiculous?

BLVR: The ways in which we’ve managed to make ourselves villains in this war are just astounding. They’re happening both on a very high level and on a personal level. We Americans used to be able to defend ourselves in the face of our government’s actions overseas by arguing that those acts were coming down from our leaders, rather than from the people themselves. But the atrocities committed at Abu Ghraib made us question that defense.

TW: They did, absolutely. And people kept supporting the war in the face of those revelations. There was a piece in the Times by a guy named William Broyles who was the editor of Newsweek for a while, editor of the Texas Monthly before that, and a marine in Vietnam. He was ruminating about the polls that show that support for the war among Americans is still pretty high. He was saying this is only possible because most of these people don’t have anybody at hazard over there, and that if you brought the draft back, those statistics would evaporate overnight. And he’s right. We’ve created this mercenary army, essentially, made up disproportionately of people from minority and economically disadvantaged backgrounds. If our own kids were at hazard our feelings about the war would change very quickly. I hate the idea of the draft, I’ve got two boys who would be eligible. But the truth is, to make these things real, we need to share the danger.

BLVR: In a way, it brings to mind one of the things we’re always trying to do as writers: to help people understand the humanity of others, the importance of other lives.

TW: Absolutely. That is exactly right. I think that’s the greatest thing literature can do, and it is a very great thing indeed.

BLVR: In the face of what’s going on in Iraq right now, what kind of responsibility do you feel like we have as writers? Do you feel like we have special responsibilities as writers?

TW: We have responsibilities as citizens. I don’t think we have special responsibilities as writers. All you can do is try to humanize people’s imaginations. I don’t know any better way to do it than to just keep on writing as you write. What is a fiction writer to do? I don’t know, except to insist on the value of what you do by continuing to do it. Because this world is continually trying to negate the value of what you do. That’s your resistance. And then, to act as a citizen in other ways—to vote, to try to get other people to vote, to protest, to boycott, to do whatever a good citizen does in support of one’s beliefs—yes, absolutely, all that. But not to turn your work into propaganda, because then you’ve become what they are. It will suck the humanity right out of your work.

BLVR: And in what direction do you see American fiction writing going now? What are some of the things you’re noticing about the work that’s different from what you were seeing ten or twenty years ago?

TW: I guess I’m seeing a little less interest in literature as a game. There’s a tremendous faith in narrative, I think—a sense that maybe it isn’t just a piece of criminal naïveté to believe that something valuable can come out of the telling of human stories. Postmodernism has forced tremendous self-consciousness upon us, perhaps against our will at times. After such knowledge, what forgiveness? You can’t ever escape what you know. We’re very self-aware as writers now, but it’s interesting to see that narrative has been reinvigorated by that, rather than abandoned. It’s given writers a new arsenal of forms, a new sophistication with which to tell their stories. Aside from that, I’m infinitely respectful of, and always in wonder at, the variety of ways that people tell stories and keep making them new.