Ever since Tracey Emin first shook up the British art world in the mid-1990s, rampaging through it in a fragile drunken rage, she has remained one of the most fascinating and controversial of the current crop of conceptual artists. She has consistently provoked a storm of contention, exposing her body and her inner self with searing honesty in a variety of media.

This year will see two major retrospectives of Emin’s work being put on by the rival top art venues in the UK, the Tate Gallery and Saatchi’s new showcase of contemporary art on the opposite side of the Thames. She also has major shows in Australia, Rome, and Istanbul. Additionally, 2004 sees the launch of her designer luggage with the French luxury brand Longchamp, and the premiere of her first feature film, Top Spot.

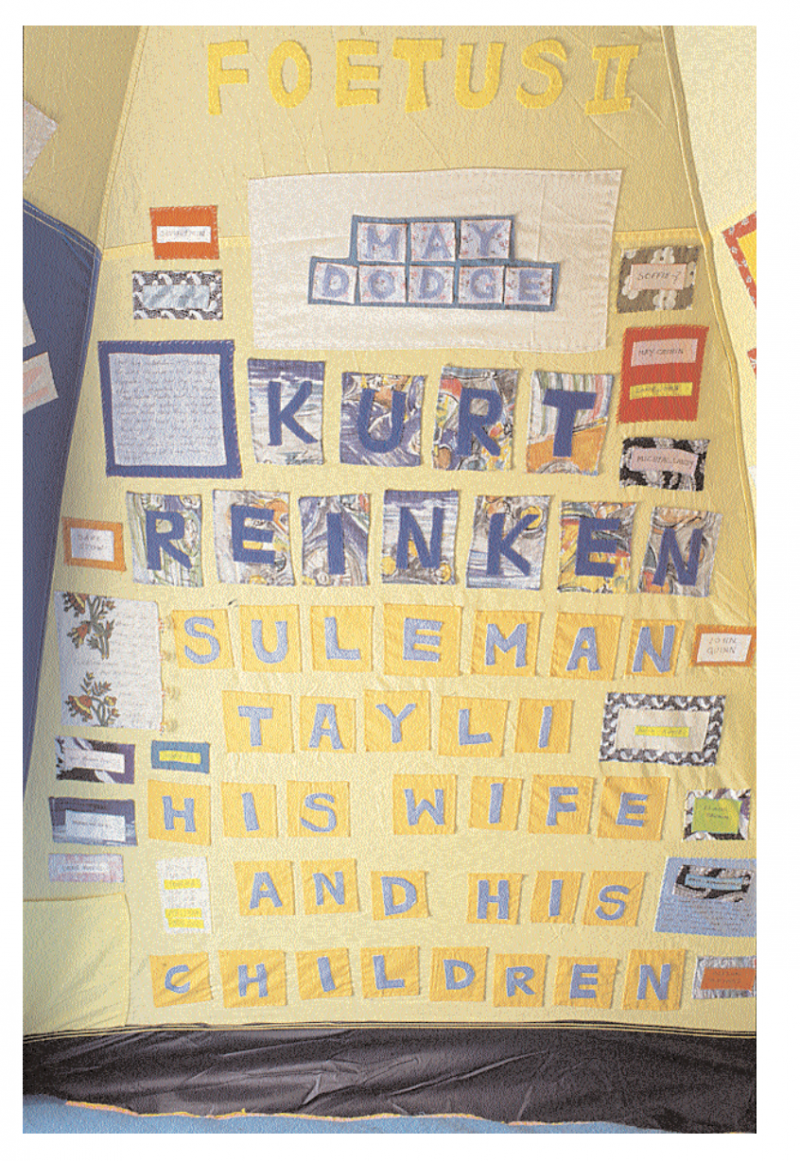

Emin’s work has played with the world of words from the beginning, and it has often been through language, as opposed to images, that she’s shocked her critics. She avoids enigmatic titles such as Untitled IX; instead we get And then you left me—Left me cold and naked (1994), a title more substantial than the flimsy print that accompanies it. More memorable perhaps was Emin’s tent, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995, with the names of everyone, from her twin in the womb to countless lovers, embroidered painstakingly inside. As she said in 2001: “It’s my words that actually make my art quite unique.”

Her first published text, Exploration of the Soul, dealt with similar themes. The Tate Gallery called it “a poetic but frequently harrowing account of her sexual history.”

This interview took place one bitterly cold winter evening. Tracey visited me at my home, and while my brothers got drunk, we had the following conversation.

—Stephan Collishaw

Tracey Emin,“Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995”, 1995. Appliquéd tent, mattress and light. 48 x 96 1/2 x 84 1/2 in. © the artist. Courtesy Jay Jopling/White Cube (London).

THE BELIEVER: Words have always played an important part in your work. As a visual artist, how do you explain that?

TRACEY EMIN: I’ve always kept a diary and I’ve always written a lot. I write short stories and even when I’m drawing I’ll start off with the title before I start the drawing. Words fill my head far more than images do. And I like the idea of art being about communication.

BLVR: Do you see words and art as being two different media pulling you in different directions? Are they struggling for your soul?

TE: No, I don’t really see it like that, because that’s basically not how people work. A person could paint hundreds of pictures of forests but they’ll never be an artist. And then you have someone like James Joyce, a writer, who will never be a writer: he’s an artist. Or, you know, there are some books that, when you hold them it doesn’t feel like you are holding words—it feels like you’re holding the world. Some artists paint and you see a whole dialogue, a conversation, place, time, a story. You don’t see it as a painting; it’s almost three-dimensional. A world, really.

BLVR: Do you think the world of words has some lessons to learn from the art world?

TE: No, not really, because we will have to wait a hundred years to see the quality of art being produced now and see how useful the experiments have been and how long they will stand up. The reason why art had to move on was because painting can only go so far. Because of that we’ve had to think of other ways to express things.

BLVR: But writing can only go so far too…

TE: Oh no, because with writing you are dealing with language and dialogue. People have to understand what they’re reading. It’s got to live. I’ve been reading Madame Bovary—it’s so descriptive. When she’s walking down the path you feel you’re actually walking with her. You can actually smell whatever is being described and see how her mind is working. To get inside somebody else’s mind and feel that you’re really there, to see the world through their eyes, is quite incredible. So with literature that’s always seemed to me to be the most experimental thing. I just read a couple of Graham Greene books. I think he was brilliantly talented but he had to sacrifice a lot for his talent. I love his books and I wouldn’t have minded going to dinner with him, but I certainly wouldn’t have liked to be in love with him.

BLVR: Your writing is very personal. What has the reaction to it been?

TE: My only problem is that my work has caused so much unhappiness, what with the press and everything. The kind of vitriolic attack that my work received has been so gross—too much—that it almost makes me afraid to be truly creative. It almost makes me feel like I should compromise. Like I shouldn’t do it. Because everyone has been so opposed to what I do. The truth is people aren’t actually opposed to what I do, it’s the bourgeois mainstream critics who are opposed to what I do, but then I’m not doing it for them anyway. I’ve been slagged off completely by the art world and I don’t know whether I fancy being slagged off by the literary world as well. It’s just too much. I do actually wake up and think, “Am I actually that bad?” I know I’m not, but there’s this big question. I have to fight the question and come back to my senses again and carry on with what I’m doing. You have to be pretty fit and mentally strong to do it.

BLVR: Are your writing and your art autobiographical or are they fictional? Would its being autobiographical make it harder for you to deal with the criticism?

TE: With a lot of the things I’ve done, I certainly wouldn’t lay myself on the line and say that’s the absolute truth, because it’s my memory, and what happened between that moment ten or fifteen years ago and now… there’s a lot of gray area. What matters is how I choose the material and put it together. As far as truth is concerned it’s very difficult to say what is and what isn’t true. What is truth? Truth doesn’t really exist. Who is going to judge whether my experience of an incident is more valid than yours? No one can be trusted to be judge of that. With any story I write, I could actually write it from three or four different perspectives, which would end with a completely different moral at the end. It’s really difficult to decide what to do now. Before it was really simple, I was just going to write a story. Now I sort of think, “Uh! Would it be more useful if I made it more fictional?” Then, on the other hand, would I be doing that just because I’m afraid of what people have been saying or how much I’m going to get attacked? The idea that I’m going to have to sit down to write some fiction where I’m going to have to think of a plot and things would really scare me, because then I think it would come out a mess. If I’m just giving people the truth, then it’s really easy. But we’ll see, won’t we?

BLVR: Do you have any boundaries in terms of what you would write about or do in your art? Do you think an artist or a writer should have boundaries?

TE: I think everyone has to have a level of responsibility. When I was younger I was more oblivious to this and there are definitely some things I would never make work about now. But then again, I don’t censor myself either; I don’t stop myself from tackling anything.

BLVR: How do you go about writing? What are your working methods?

TE: I get a piece of paper and I sit down and write.

BLVR: You’re a pen-and-paper person?

TE: I can’t use a computer. I can’t use a typewriter.

BLVR: Oh, come on Tracey, everybody can…

TE: No that’s not so. Graham Greene wrote 200 words a day; I write about two thousand in a couple of hours. This is why I don’t like to use a PC. If I write “Tracey Emin is thirty-eight,” it takes me about a second to write, but if I use the computer it takes about five minutes. And I get really frustrated about the fact that I can’t spell. Then with my editing process, I’ll move paragraphs around or I’ll cut pieces out, but I won’t go looking for the perfect word, because the way I write is so simple, you know, it’s hard to intellectualize that. The first edit goes on inside my head. When I’m lying in bed at night, I write in my head. This afternoon I went ice-skating and there were some kids who were really fast, really menacing. I was skating really slowly and I was thinking Ice Demons and then I thought about the idea of this scene with people skating and there is this kid, a little boy about seven, and he’s really fast. Then he pulls his hat off and he’s got really, really long hair. It’s a girl. It’s just a really simple thing. All my ideas are really simple. But it was something I saw visually, and that’s how my writing starts.

BLVR: Do you find you use the same creative process in your writing as with your visual art?

TE: Yes. When I’m writing I’m not thinking “he says, she says, this happened”; I think action.

BLVR: Is the writing in your art consciously naïve?

TE: You have to understand, with the prints, that I’m writing backwards. Each drawing takes me about a minute to do. You have to be really gentle and write really quickly. In Exploration of the Soul all my spellings were corrected. When the time came for it to be printed I had to choose whether it was going to be printed in my handwriting and whether it was going to be my own spelling. I decided to have it beautifully printed—a really nice print. So we couldn’t keep the spelling mistakes in it because it would have looked really stupid. I write using stream-of-consciousness and I think my work isn’t important in the detail but in the whole.

BLVR: Do you have an imagined audience for your writing?

TE: No, I don’t have an imagined audience. Weird! Only if I’ve been trying to say something to somebody, then that carries on into my writing.

BLVR: There is talk of your having a book deal. Can you tell me some more about it?

TE: It was quite funny. I happened to mention in an interview a few years back that I would like to write a book. Some publishers read the interview and they approached me and said they would like to publish it. Penguin were the first people interested, but I had three publishers altogether who wanted to do the book deal.

BLVR: But where do you find the time to write, between your art, the interviews, and all the other things you do—never mind your infamous social life?

TE: It’s difficult and I don’t do it all the time. Like last month I had to do some writing for a catalogue and they bullied me to get it to them by the twelfth. On the fourteenth they rang me to ask where it was. I told them I was just faxing it through then. Truthfully, I wasn’t. I just sat down when I got off the phone and thought, I’ve got to do it now. So I sat down and did it and faxed it through. I don’t give myself time to think, is it good or not? I just do it. I agreed to do the book a few years ago, but it’s been so difficult finding the space to work on it that I wanted to give the money back, but they wouldn’t let me. They said that I could have more time. The thing is they trust that I’ll do it and the fact is that they wouldn’t be able to get me to do the book now for the kind of money they paid me four years ago. They got a good deal and they know it. BLVR: You’ve used letters a lot in your art. What role do you think they have to play, both in terms of your own art and writing in general?

TE: I write lots of letters. I’ll write four pages, and then I’ll write the person a couple more at the same time and put them all in the envelope. I like this kind of writing. It’s free. It’s for an audience Every artist has something that acts as a backbone to what they do. For some artists that may be photography or formal sculpture, but for me it has always been how I think about things. The concept behind the art. Writing has always been the easiest way to convey that concept, so letters are important.

BLVR: You’ve been doing lots of different kind of things recently. You’ve modelled for Vivienne Westwood, the punk designer, you’ve designed luggage for a top label, and then there is the film that you are making with the BBC.

TE: My film Top Spot is something I’ve been working on for the last six months. At the moment it’s quite frustrating because I can’t wait for people to see it. It will be released in cinemas in the UK in the summer of 2004 for three months, and then it will go onto television.

The story is about girls growing up with the usual pitfalls and daydreams of being an adolescent. It’s set in Margate [the provincial seaside resort where Emin grew up; much of her earlier work refers to Margate]. It’s not gloomy. There’s a bit about teenage sex and teenage mums, because where I grew up there was a lot of that. But it’s not going to be a hardcore kitchen-sink film. It’s really beautiful to look at. It’s about growing up by the sea. One thing I’m certain of is that the people who like my work are going to like it and the people who don’t like my work won’t.

I felt really flattered when the BBC approached me. It was brilliant at that time because the art world didn’t appreciate me, so I wanted to go somewhere I would be wanted.

It’s great to be doing lots of different things. I feel like I’ve got to keep moving. People talk about the level of my ambition, but I don’t have any real ambition with my work in terms of getting somewhere. All my ambitions are really personal.